Located in the St. John the Baptist Parish, the Whitney Plantation is, according to its website, “is the only plantation museum in Louisiana with an exclusive focus on the lives of enslaved people.” In the 100-plus years of history of its activity, three-hundred and fifty enslaved Africans were forced to grow indigo, sugar and rice on it, making the Whitney Plantation one of the wealthiest businesses, not only in the American South but of the United States.

In the early 1700s, Europeans from Spain, France and Germany lived in Louisiana, where Indigenous Americans had long been settled. While there were Europeans who worked as indentured servants, they were contracted to only thirty-six months of labor, primarily clearing land to work on small tracts of land, Indigenous Americans were exploited for much longer periods of time. In 1712, there were only 10 Africans in the entire state of Louisiana. However, because of the brief periods of indenture servitude as well as “White” nationalism and its costs, including disease, collective rebellion and brutal treatment of utilizing Indigenous Americas, Africans became more viable to use to build southern society.

Africans, as a whole, were a perfect solution to be forced to labor in building America. Africans had prior experience of building their own empires. They had a strong immune system, greater enabling them to work among the Europeans. They were already skilled professionals, ranging from farming to smelting, healing to cooking. Their skin tone made them easy to identify in the instance of escape. With their homelands being across the Atlantic Ocean, the Africans could not physically return home, should they survive the brutal Trans-Atlantic travels. They were completely unfamiliar with the terrain in the United States. Finally, it was incredibly difficult for Africans to unite against their oppressors, as many mechanisms, including cruel punishments, rape and murder, were often used to keep them divided.

In 1719, the first two vessels carrying captive Africans docked in Louisiana from the West Coast of Africa. On it, were men who were rice farmers; their knowledge and expertise would transform Louisiana into becoming one of the wealthiest states in America.

In 1722, approximately 170 Indigenous Americans were enslaved on plantations throughout Louisiana and their intermixing, including marriage, with the Africans were common. In Louisiana, the Africans were primarily from the Bight of Benin, the Bight of Biafra, Senegambia and West-Central Africa with a small population originating from Southeast Africa.

In 1795, about 2,800 Africans and their descendants were enslaved on the German Coast, where the Whitney Plantation is located; there were approximately 20,000 enslaved Africans and an estimated 16,000 free people of color in Louisiana. Although the Trans-Atlantic slave trade was outlawed by the United States in 1807, the trafficking of Black humans did not cease or diminish; they were simply sold domestically, coming from the Upper South to Louisiana. Many thousands more would be victimized through the illegal international slave trade, smuggled in from Africa and the Caribbean. By 1860, the number of free people of color remained stable but the population of enslaved Africans soared: those persons enslaved on the German Coast, alone, more than tripled to almost 9,000 and there were more than 330,000 Blacks enslaved in Louisiana.

On the German Coast, enslaved Africans, as per the website of the Whitney Plantation, “cleared the land and planted corn, rice and vegetables. They built levees to protect dwellings and crops. They also served as sawyers, carpenters, masons and smiths. They raised horses, oxen, mules, cows, sheep, swine and poultry. Enslaved people also served as cooks, handling the demanding task of hulling rice with mortars and pestles … they preserved the foodways of Africa.”

Those enslaved were forced to suffer a grueling life, including working from sun-up to sundown with little tools. Those who worked in the main house on a land tract were on call twenty-four hours per day to labor at the demand of the slaveowners and in general, anyone “White”. Enslaved women had to care, even as wet-nurses, for their master’s family, at the detriment of being able to take care of their own families. There were no protections available for those enslaved and it was extremely difficult for a family to remain intact, as the threat of being sold away was forever looming. In order to create a semblance of family, often those enslaved took care of others to whom they were not related by blood, identifying their connection as “fictive kin”.

The new life enforced upon the Africans and their descendants was incredibly harsh. Resistance and rebellion did occur during slavery and the consequences for these were immeasurably vicious. Those who were caught could be branded with a hot iron, mutilated, sold away or even executed. On the museum’s website, you will learn that “the runaway slave, who shall continue to be so for one month from the day of his being denounced to the officers of justice, shall have his ears cut off, and shall be branded with the fleur de lys on the shoulder; and on a second offense of the same nature, persisted in during one month from the day of his being denounced, he will be hamstrung, and be marked with the fleur de lys on the other shoulder. On the third offense, he shall suffer death.”

In Louisiana, maroonage, or escape, was a common and enduring act of resistance since the beginning of slavery until the ending of the Civil War. Those who escaped slavery would run away to live in the swamps and they were called “maroons”. They practiced guerilla warfare, including killing farm animals and taking food; grew crops and herbs; created crafts from natural materials; hunted and fished. Some maroons were even independent laborers and vendors in marketplaces of larger cities, especially New Orleans, in Louisiana. In the 1770s, the maroons of Louisiana, led by Saint-Maló, controlled the Bas du Fleuve, the area between the mouth of the Mississippi River and New Orleans. Saint-Maló had been a slave of Karl d’Arensbourg, the leader and commander of the militia of the German Coast. Saint-Maló and his companions were eventually captured, tried and hanged on June 19, 1784 by Spanish authorities.

On the Whitney Plantation, perhaps what is most powerful and moving is the memorial to the 1811 Revolt. This graphic memorial is acknowledged with silence to honor those brave men, primarily led by Charles of the Deslondes plantation, who were executed for striking for their freedom.

On January 8, 1811, enslaved Blacks from the St. Charles, St. John the Baptist and St. James parishes walked downriver towards New Orleans. The insurrection was led by several men of diverse origins, including from Africa, and its main leader was Charles, a mulatto who was born on the plantation of the Widow Jean-Baptiste Deslondes. The goals of the group were to gain their freedom, free all those enslaved and capture New Orleans. The insurrection started on the land of Manuel Andry in St. John the Baptist parish and Andry was the head of the parish’s local militia. Though poorly weaponized, they destroyed parts of plantations and killed two White men. After two days, those formerly enslaved lost to the local militia, which was supported by federal troops. Approximately thirty insurgents died in battle.

From January 13 to January 15, forty-five captured Black men were put on trial at the plantation of Jean Noël Destrehan, who also was one of the five jury members. The death penalty was handed down and each of the men would be shot to death in front of the plantation from which he was forced to labor. Though the deaths would be delivered without torture, the heads of those executed would be decapitated and planted on poles throughout the parishes as warnings to any future rebellions.

On January 16, 1811, the planters requested of the courts a temporary end of arrests, which the St. Charles Parish courthouse honored. The reason for this was because their economy was suffering due to the loss of the young Black men who were killed. Those who died in action and those executed were between the ages of twenty and thirty years old and they worked as “sucriers (sugar makers) or experts of “roulaison” (harvesting of sugarcane). By January 18, twenty-seven slaves were still missing, most of them hiding in the woods. Twenty-two insurgents, including twenty in New Orleans, were still awaiting judgment which later led many of them on the scaffold or before a firing squad.

By January 18, twenty-seven “rebels” were still missing; twenty-two, of which twenty in New Orleans, and the remaining in the woods, were tried and executed by a firing squad or by hanging. Likening these men’s fight for freedom to those who are considered “Patriots” in American colonial history, text of the museum at the Whitney Plantation states, “Although they did enjoy nothing but few precious hours of freedom, their action is comparable in its principle to that of the founding fathers who signed the Declaration of Independence, knowing that they would be hanged if they lost the War of Independence.”

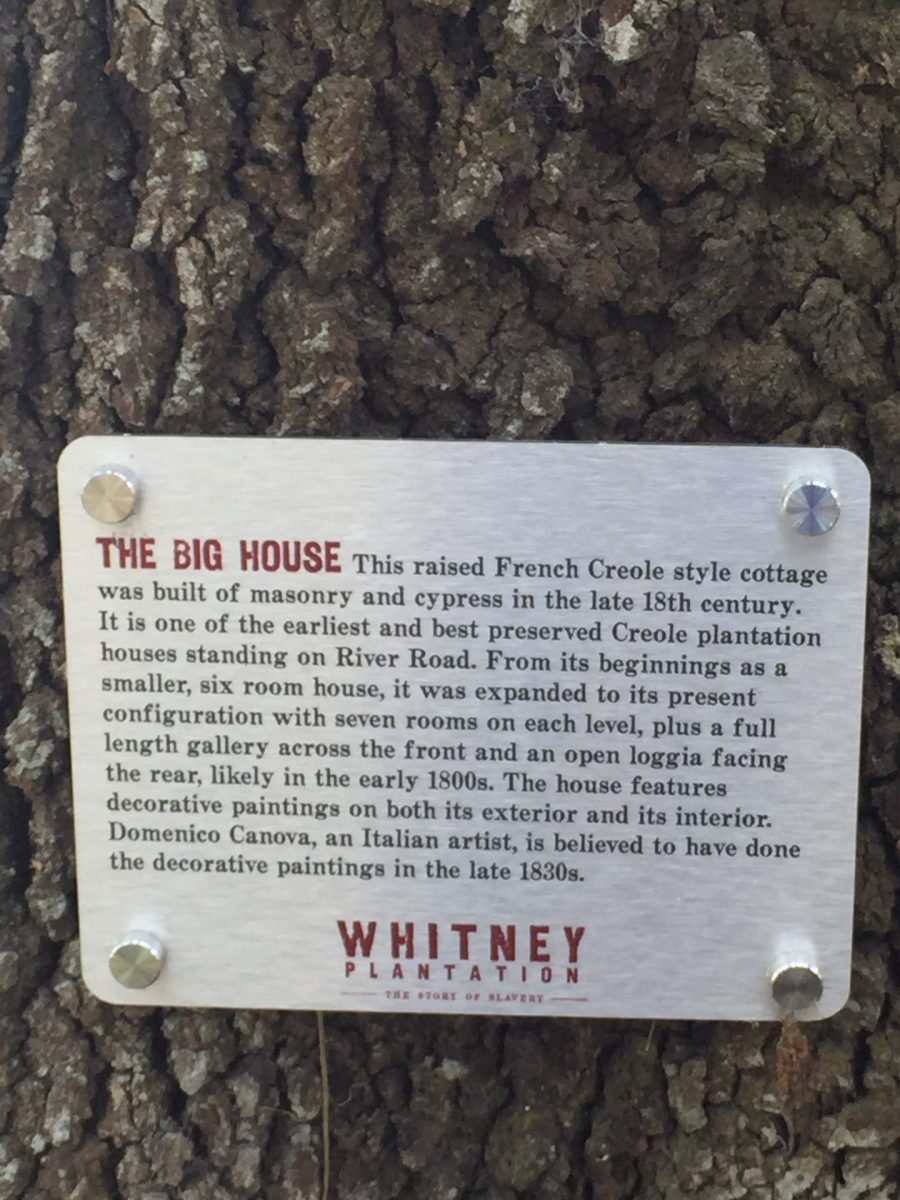

Situated on River Road, alongside the Mississippi River, the Whitney Plantation was founded by Ambroise Heidel in 1752. An immigrant from Germany, Heidel purchased this land tract when he was about fifty years old. He and his wife, Marguerite, and their descendants: youngest son, Jean-Jacques, Sr.; grandsons, Jean-Jacques, Jr. and Marcellin; and granddaughter-in-law and widow of Marcellin, Marie Azélie owned it until 1867.

During their ownership, their surname “Heidel” was Anglicized as “Haydel” and the name of the plantation was “Habitation Haydel”. It was under Marie Azélie that the plantation was converted to one of the most successful enterprises in America; in one grinding season, 407,000 pounds of sugar was produced. This success was due to the harrowing and arduous labor that hundreds of enslaved Africans and their descendants were forced to undertake.

The success of Marie Azélie was vast and she, shortly before her death in 1860, was listed among those slaveholders who held the greatest numbers of enslaved Africans in all of Louisiana. One hundred and one persons comprised the work force who labored for free for most, if not all, of their lives on the plantation. Her estate, valued at an estimated $187,000 at that time, would be valued at $5, 770, 932.65 in 2019. It contained a French Creole main house, which was constructed in 1803, several outbuildings, slave quarters, an outdoor kitchen and dovecote.

Also, during her time, Marie Azélie commissioned the creation of frescos and murals to decorate the exterior and interior of the main house. These pieces were created in dedication to her late husband, Marcellin. She, according to the museum’s website, had his initials “monogrammed in cartouches and disposed at the four corners of the paintings drawn on the ceiling of the upstairs living room. This was very likely done in the 1840s when increased tariff protection generated higher profit and the subsequent rise in the number of sugar plantations.” The art work, which still adorns the main house, has been attributed to famous artist, Dominici Canova, whose work includes numerous paintings and frescos featured throughout New Orleans and its surrounding areas. Pieces of Canova’s work can be seen at the St. Louis Cathedral and the San Francisco Plantation, which was owned by the Marmillions, close relatives to the Haydel family.

The commissioned artwork positioned the main house of the Haydel property as exclusive in Louisiana, in particular, and in the South, as a whole; it is the only known example of exterior decorative painting to have even existed in Louisiana at that time. Its beauty and extravagance signaled that the Haydels were scions of wealth and culture, at the cost of the humanity, and all of its aspects, of the hundreds of Blacks they enslaved.

In 1867, the plantation was sold to Bradish Johnson, a businessman born in New Orleans but who was reared and lived primarily in New York; he would name the plantation after his grandson, Harry Whitney. There would be several owners over the next century and one-half, including the Formosa Chemicals and Fiber Corporation, who bought the plantation in 1990. Their original intent was to erect the largest rayon plant in the world at the plantation site.

However, obstacles, such as protests by local environmental activist organizations; discovery of archaeological, anthropological and historical significance and a declining demand for rayon, prompted Formosa to sell it to John Cummings, a trial attorney of New Orleans, in 1999. Cummings spent almost fifteen years and greater than eight million dollars of his own to fund the restoration, renovation and conversion of this plantation into a museum property.

In December 2014, the museum and its accompanying facilities such as a freedmen’s church, a plantation store and an overseer’s house, on the two thousand-acre Whitney Plantation was opened to the public. On this land tract is the only surviving French Creole barn in Louisiana and two of the quarters for those enslaved, though original, were transferred from another plantation. The 1884 Mialaret House and its accompanying structures and land, on which sugarcane still grows, represent the extensive history of slave labor on the plantation.

Cummings commissioned memorials built to honor over 100,000 people enslaved in Louisiana and original art, including life-size sculptures of children, to support the museum’s purpose in allowing visitors to better understand the life of the people, especially those enslaved, on a Louisiana plantation. The sculptures represent the children on the plantation who were born into slavery before the Civil War; as adults during the Great Depression, they were orally interviewed about their lives by workers of the Federal Writers Project in order to preserve their stories. The federal government collected and made available to the public the numerous transcripts and audio recordings of hundreds of the last survivors of slavery and much of this can be accessed at the Library of Congress.

Highlighted as a site on the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail, the Whitney Plantation receives thousands of visitors annually. As such, they offer only guided tours of the land tract and the structures on it. Due to the high volume of visitors and its popularity, it is highly advisable to purchase tickets online in advance to greater ensure the possibility to experience the plantation, as it often sells out, especially from March through July. Tours begin on the hour and last approximately ninety minutes. On the guided tour, you will receive an identifying lanyard which features the name and an abbreviated account of a child who was enslaved on the plantation. Because much of the tour is outside, it is recommended to dress accordingly, including wearing comfortable walking shoes and breathable clothing. Guests should also be prepared with umbrellas, sunscreen and insect repellant.

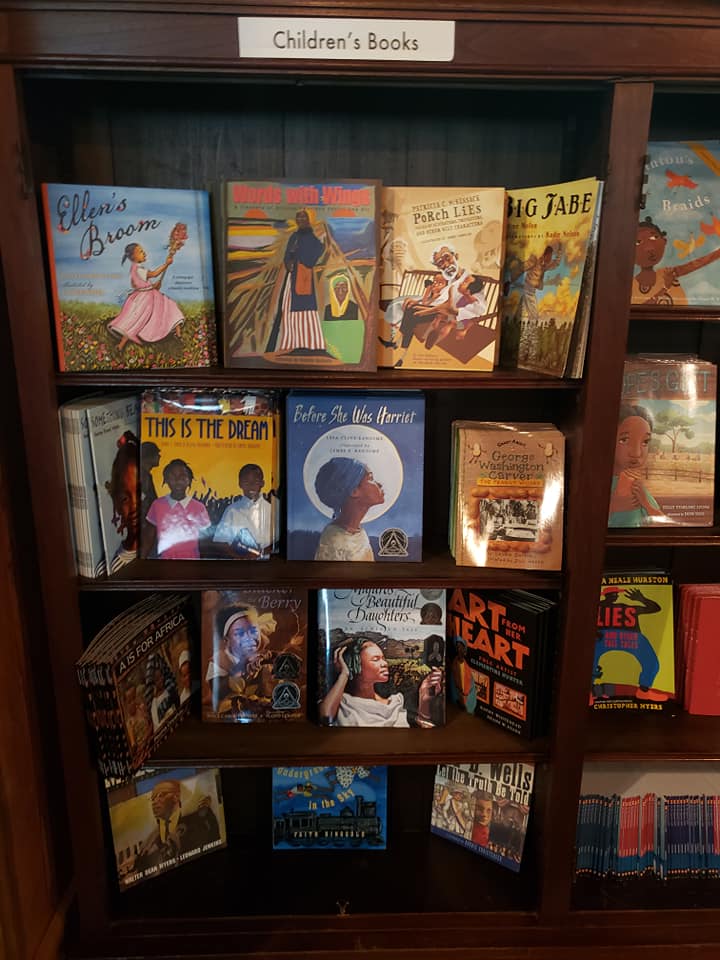

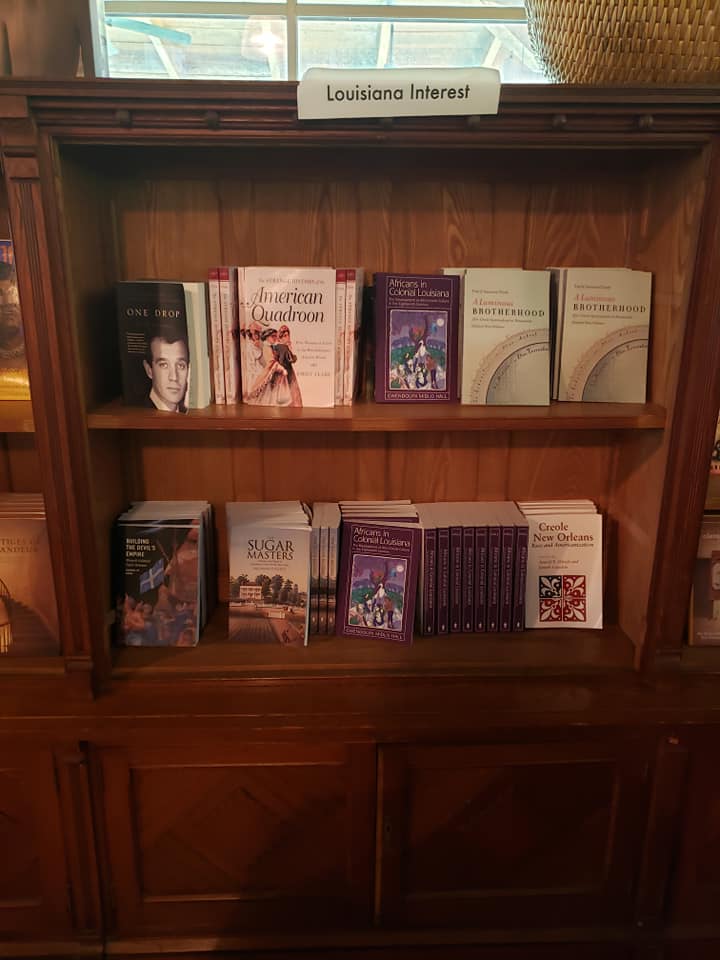

Inside the visitor center at the Whitney Plantation, guests may guide themselves to view two exhibits: the permanent Slavery in Louisiana and a rotating, temporary exhibit. In the center, cold drinks and snacks, such as ice cream, are for sale and there is an intimate, uncovered area that contains tables and seating. The possibilities of attaining a memento from your visit ranges wide, from textiles and art to handmade jewelry and DVDs. They also have a stellar collection of books available for purchase, both for adults and children!