“You have proved to be one of the great leaders of our time. Through your efficiency as an administrator, your genuine humanitarian concern, and your unswerving devotion to the principles of freedom and human dignity, you have carved for yourself an imperishable niche in the annals of contemporary history.”

~ Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in tribute to Wilkins’ 30th anniversary with the NAACP

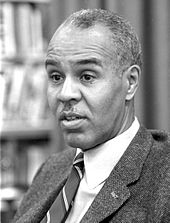

Roy Wilkins was born to William and Mayfield Wilkins in St. Louis, Missouri on August 30, 1901. Both his parents had graduated from college and his father also studied for ministry in the Methodist church. The Wilkins family had moved to St. Louis from Holly Springs, Mississippi because, despite his formal education and aspirations, William was unable to obtain appropriate work to support his family in his hometown. Relocating to the more bustling and prosperous city, the only work William could secure was tending a brick kiln.

By the time that Roy was four years old, his mother, Mayfield, passed away after suffering from tuberculosis. William sent their three small children to live with their maternal aunt and her husband, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Williams in the Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul, Minnesota. Living in an integrated, low-income community, the Williams lovingly reared the children; as such, these two adults were often regarded by Roy as his parents. The aunt and uncle emphasized the immeasurable values of education, virtue and honor. These would be essential in overcoming the never-ending obstacles that many African-Americans faced in life.

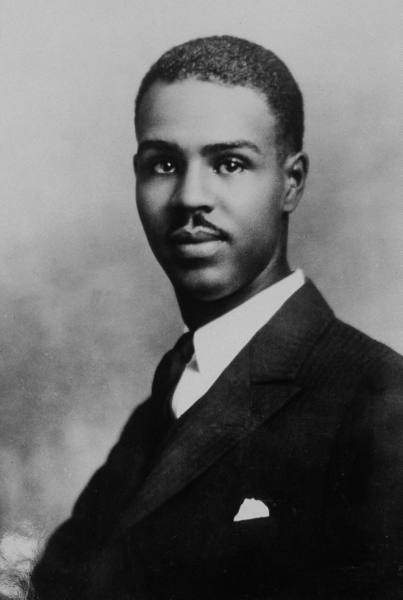

In his community, there were few Blacks so Roy Wilkins attended integrated schools, including Mechanic Arts High. There he excelled in academics and his activities included reporting and editing the school’s newspaper. After graduating from high school in 1919, he matriculated the University of Minnesota, where he majored in sociology. He worked in a slaughterhouse and as a Pullman porter during this time to support himself and pay for his education.

(No copyright infringement intended).

However, Roy Wilkins was passionate about journalism. Though he maintained a full academic courseload and worked, Wilkins served as a journalist and night editor of the Minnesota Daily and editor of the St. Paul Appeal. The Minnesota Daily was the university’s newspaper, and the St. Paul Appeal was a weekly newspaper geared towards Black readers. Learning of lynchings of Blacks in Duluth prompted Wilkins’ immediate and comprehensive involvement in civil rights. His actions included joining the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and being vocal in writing and speeches. In fact, while at the university, he won first prize in an oratorical contest for his fiery delivery of an anti-lynching address.

In 1923, Roy Wilkins graduated from the University of Minnesota with a Bachelor of Science degree in sociology. He moved to work as a journalist at the Kansas City Call, a prominent Black newspaper. Before long, he was promoted to its managing editor.

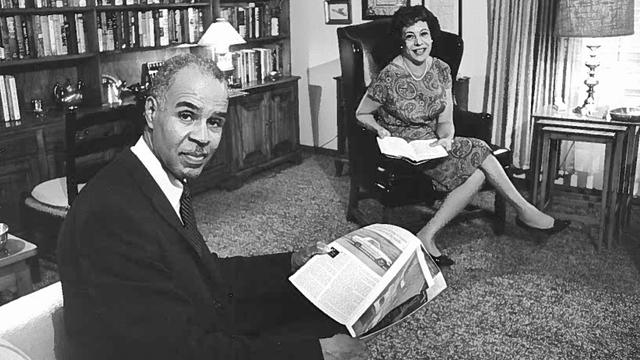

During this time, he began courting Aminda “Minnie” Badeau, a social worker. In 1929, Roy and Minnie married. Although they would have no children of their own, they reared the two children of their great friend, Hazel Wilkin Colton, a writer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Hubert Humphrey School of Public Affairs.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Roy Wilkins believed the best way to battle the system for positive change and attain civil rights was to change it from within. He used the Black newspaper as a platform to denounce Jim Crow segregation and encourage voting, as he understood the ballot could be used to remove racist politicians. In 1930, for instance, Wilkins and the newspaper led a campaign to unseat Senator Henry J. Allen (R-KS). According to the biography of Roy Wilkins at Encyclopedia.com, the campaign “was successful and became a harbinger of the political advances to come for Southern Blacks.”

His lead of the campaign to unseat Allen and superb editorial work at the Kansas City Call greatly impressed Walter F. White, the Executive Secretary of the NAACP. White offered a position within the historic civil rights organization to him and in 1931, Roy Wilkins moved to New York City, becoming the chief assistant to White. Wilkins work, at times, was dangerous and his investigations ranged from uncovering working conditions for African-Americans in the South to advocating anti-lynching laws. He even went undercover as a laborer in levee camps in Mississippi, where he later reported on the extensive exploitation, including price-gouging and inferior living conditions, of Blacks by Whites!

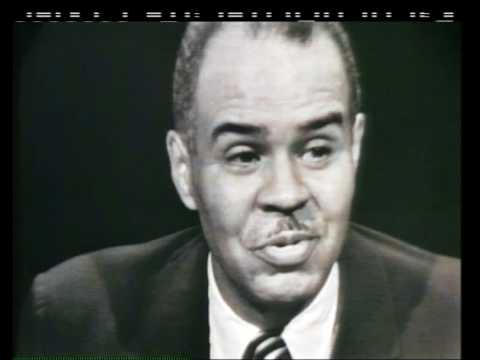

In 1934, W.E.B. DuBois, co-founder of the NAACP, left the organization and ceased being the editor of The Crisis, the organization’s magazine. DuBois advocated a separatist approach to empower Blacks, which was contrary to the views of some leaders within the NAACP. Roy Wilkins succeeded DuBois in the national editor position and would serve in this capacity for fifteen years. During that time, he both increased national readership and greatly decreased the organization’s debt. Soon after becoming editor, Wilkins assumed another national position, Administrator of Internal Affairs, within the NAACP. He also worked as an adviser to the War Department during World War II.

From 1939 until 1949, Roy Wilkins edited the NAACP’s periodical while concurrently directing the organization’s national anti-discrimination program. In 1949, he accepted the position of chairman of the National Emergency Civil Rights Mobilization, a collective comprised of more than one-hundred local and national organizations.

In 1950, Wilkins, on behalf of the NAACP; A. Phillip Randolph, founder and president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; and Arnold Aronson, a leader of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council united to create the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR). According to the biography of Wilkins on the website of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, “LCCR has become the premier civil rights coalition, and has coordinated the national legislative campaign on behalf of every major civil rights law since 1957.”

He was integral in many legal cases involving civil rights including the groundbreaking Brown vs. Board, which ended “separate but equal” policies, in 1954. In 1955, his mentor, Walter F. White passed away and Roy Wilkins accepted the NAACP’s offer to assume White’s position as Executive Secretary of the national civil rights organization.

As the Executive Secretary (this title was changed to “Executive Director” in 1964), Wilkins’ approach was to use legislative and legal means as opposed to nonviolence tactics that were implemented by leaders, such as Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Although they privately disagreed on the most successful means to attain civil rights, they agreed that more than one approach would be needed and were respectful of each other, especially in public.

(No copyright infringement intended).

This was critical so that a united front of Black civil rights leaders was seen by all. Wilkins and the NAACP provided legal defense to King, Jr. and members of his organization, Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). Its local branches were encouraged to donate to the de-segregation efforts in Montgomery, which included the Montgomery bus boycott. King, Jr. even gave credit to Wilkins and the NAACP, as per the biography on the NAACP leader from the website of the King Institute at Stanford University. In the King Papers, King, Jr. affirmed, “I have said to our people all along that the great victories of the Negro have been gained through the assiduous labor of the NAACP.” Similarly, Wilkins praised King, Jr., as the King Papers also share that the Executive Secretary saluted the minister’s Birmingham Campaign as it “made the nation realize that at last the crisis had arrived.”

Leading the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Roy Wilkins participated in protests, boycotts and marches, including the March on Washington in 1963, the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965 and the March Against Fear in 1966.

One of the most powerful acts, early in leading the NAACP, was his involvement with Dr. T.R.M. Howard of Mound Bayou, Mississippi. Howard, Wilkins and other civil rights activists sought to protect Black Mississippians from financial exploitation by members of the White Citizens Council.

Howard led the Regional Council of Negro Leadership, a powerful civil rights organization in Mississippi. They conceived a plan in which Black businesses and organizations moved their accounts from local banks to Tri-State Bank in Memphis, Tennessee. The money re-located to Tri-State Bank allowed the Black-owned financial institution to offer greater savings, financial planning and loans to its Black members.

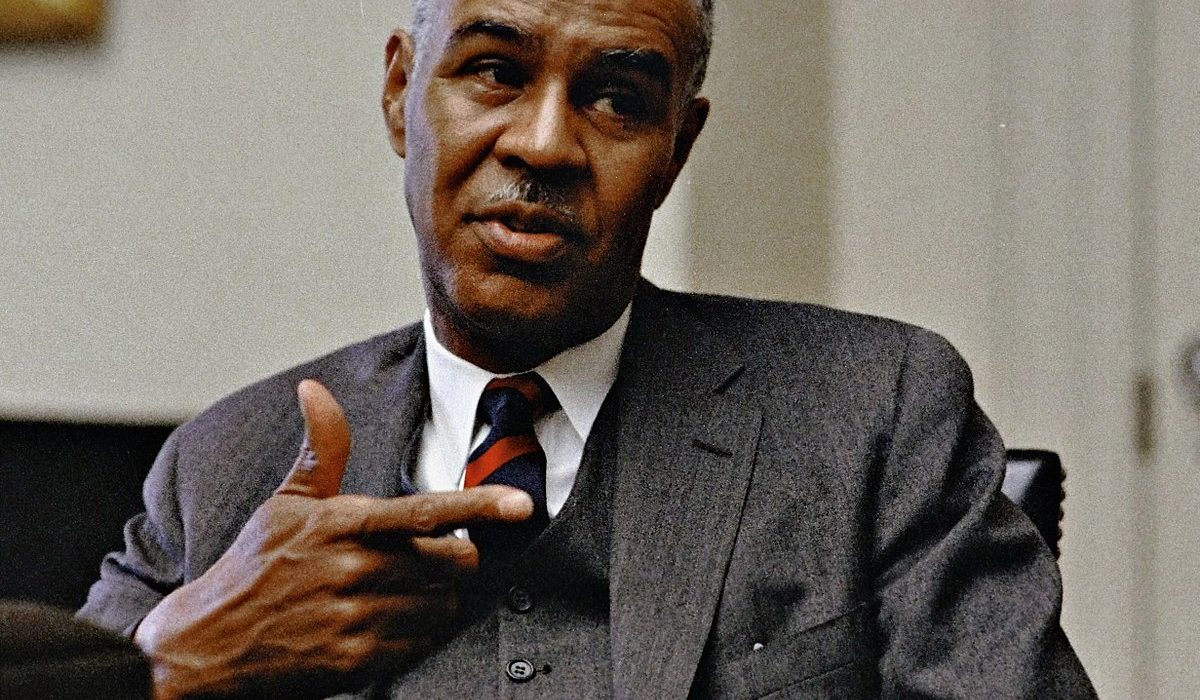

By the early 1960s, Roy Wilkins led the largest civil rights organization in the world. Numbering more than half a million members, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was a powerful force with which to reckon. Wilkins levied this power over the next decade to promote the agenda of civil rights. He testified at Congressional hearings; presided over the passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1960, 1964 and 1965; and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Wilkins also conferred about civil rights issues with Presidents Harry D. Truman, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard M. Nixon, Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter. Digital copies of his correspondence with President Kennedy are held at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

Roy Wilkins felt that the most effective way for African-Americans to be “American” was their complete involvement in the system. As such, he led the NAACP to work within the system, specifically in law and politics, to achieve its goals which included fair housing, greater employment opportunities, integrated public accommodations and increased voting rights. Extending his work globally, Wilkins, in 1968, served as chairman of the U.S. delegation to the International Conference on Human Rights.

As the Civil Rights Movement continued to build, the Black Power Movement, which was more militant, was birthed. Wilkins was vehemently against the latter, likening it to a separatist movement akin to a reverse Ku Klux Klan. By the late 1960s, Wilkins was vilified by many in the Black Power Movement. In the biography on him at Encyclopedia.com, Wilkins, however, stood his ground, confirming “I did not intend to let [them] sway the NAACP from its fundamental goal: the full participation of Negro Americans in all phases of American life … The goal had always been to include the Negro in that mainstream, to create a new sense of dignity and personal worth, to secure equal opportunity.”

For almost the next decade, Roy Wilkins continued to lead the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in a conservative direction. At times, he was at odds with others in leadership, whether they were in other civil rights organizations or it be the board of directors at the NAACP. In 1977, Roy Wilkins retired from leading the NAACP and became the Executive Director Emeritus. Although he never groomed a successor, Dr. Benjamin Hooks was elected to assume Wilkins’ position as Executive Director.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Wilkins continued to work within the field of civil rights. Roy and Minnie Wilkins lived quietly in their home in New York City. Having defeated cancer in 1946, he remained healthy throughout much of his life. In 1980, he began to experience issues with his heart and kidneys.

On September 9, 1981, Roy Wilkins passed away due to kidney failure that was instigated by heart issues; he was eighty years old.

Fortunately, Wilkins had written about his life and in 1982, his autobiography, Standing Fast: The Autobiography of Roy Wilkins, was released posthumously.

In his eulogy of Wilkins, Hooks praised, “Mr. Wilkins was a towering figure in American history and during the time he headed the NAACP. It was during this crucial period that the association was faced with some of its most serious challenges and the whole landscape of the Black condition in America was changed, radically, for the better.”

The recipient of numerous awards and honors, Roy Wilkins was given the Spingarn Award by the NAACP in 1964 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Johnson in 1967. There is a prize named in his honor for young adult excellence in academics and the arts given by the NAACP. In 1992, the Roy Wilkins Center for Human Relations and Social Justice was established at the Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota. Also in his adopted home state, the St. Paul Civic Center Auditorium was renamed the Roy Wilkins Auditorium in 1984 and a memorial was erected in tribute to him on the Mall of the Minnesota State Capitol in 1995.

In 2001, the United States Postal Service honored Wilkins with a stamp and the following year, he was named as one of “100 Greatest African Americans” by Molefi Asante. Roy Wilkins Park in the Queens borough of New York City was created in tribute to the dedicated civil rights leader. Additionally, award-winning actor Joe Morton portrayed Wilkins in the 2016 film, All the Way.

“It became apparent to me at a very early age that the Negro population in this country was such a small minority that we had to study our approaches very carefully. The word today is ’powerlessness,’ but we had even less power in those early days. We had no vote in the South. No political influence. No standing whatsoever in the courts. No legal protection. At one time, the U.S. Supreme Court was actually considered as our enemy. If you decided to really fight back, you had to be prepared to die … If we had chosen the path of violence 40 or 50 years ago, we would have committed genocide on ourselves.”

~ Roy Wilkins