“He wrote every day of his life and on the day he died, in his jacket pocket, there was a note to a dear friend that he himself never got the chance to deliver. The note ended with the following quote: ‘On Sunday, I try to write more.’”

~ Charles Micheaux, actor

Long before Reggie Hudlin, Kasi Lemmons, Robert Townsend, Oprah Winfrey, Tyler Perry, John Singleton, Mattty Rich, Ava DuVernay, husband-wife duo Reggie Rock Bythewood & Gina Prince Bythewood, and Spike Lee, there was Oscar Micheaux. A film director, independent producer, writer and entrepreneur, Micheaux wrote, directed, produced and distributed 48 films and, additionally, authored 7 novels throughout a career that spanned three decades (1917-1948)!

“The Czar of Black Hollywood”, Oscar Deveraux Micheaux was the fifth of thirteen children born to Calvin and Belle Michaux on January 2, 1884 in a small community near Metropolis, Illinois. The Michaux family believed strongly in the value of education. As they struggled to live beyond survival on their small farm, the Michaux parents moved to Metropolis for better opportunities and access for their children to become educated. Over time, however, life in the city became an even greater struggle and the family returned to their farm. Oscar, who was very bright, became rebellious upon their return and his father sent him back to Metropolis to find his own way in the world.

At seventeen years old, Oscar would leave Metropolis to live in Chicago, a growing hub of African-American culture primarily due to the migration of Blacks from the American South. In “The Windy City”, Michaux, worked in various environments, including steel mines and the stockyards, performing numerous jobs as a factory worker, coal miner and a Pullman porter. About this time, it’s believed Michaux added an “e” to his surname, changing its spelling, “Micheaux”. A strong supporter of individual initiative and self-reliance, he was greatly inspired by the teachings and real-life example of Booker T. Washington. Washington, an African-American author, orator and advisor to United States presidents, served as president of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (presently known as Tuskegee University), a historically Black university. What inspired Micheaux the most about Washington, however, was his support of Blacks as entrepreneurs. He was one of the founders of the National Negro Business League, which had as a primary goal to promote the interests of Negro businesses.

Because of this inspiration and having been cheated of his pay by an employment agency, Micheaux worked hard, saving his earnings in order to begin his own business. He started a shoe shine business and would later be employed in December 1902 as a Pullman Porter. From the latter, he would become financially stable because of the illegal practice of taking “knockdowns.” “Knockdowns”, in which a porter would provide a superior service that was not standard, provided a means of extra pay by the traveler.

Micheaux also broadened his horizons by traveling all across the Unites States and connected with wealthy Whites who could afford to travel on the luxurious “hotel on wheels” of the Pullman trains. After three years of working as a porter, he had accrued a roster of esteemed social contacts and a substantial savings of $2300 (the sum equates to approximately $70,000 USD in 2019), from which he, in 1904, bought a tract of land in Gregory, South Dakota. Micheaux, the only African-American in his community, became a successful homesteader. During this time, some accounts state Micheaux fell in love with a daughter of a White homesteader. There are varying reasons, from racism, not allowing the two to be a couple, to Micheaux suppressing his feelings out of loyalty to Black people, why their union did not work. However, other accounts do not mention this alleged affair.

What is known is that in 1910, Oscar Micheaux married a Negro woman, Orlean McCracken, the daughter of a prominent preacher in Chicago. In several readings on the life of the filmmaker, it is believed that the McCracken family, who was well-to-do, did not believe that Oscar was of quality economic and social standing for Orlean. The simple and difficult life on the homestead and his neglect of her was greatly compounded by the stillborn birth of their son. Oscar was away on business when she experienced the loss of their infant. It seems it was the final straw for Orlean, who took their savings to leave Oscar and return to her family in Chicago. Her father sold the property that Oscar owned and Micheaux’s pleas for his wife and monies to be returned were strongly denied.

The painful impact of these life events would become the basis of a series of books he decided to write. In the series, one in particular, The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Homesteader, was published by a small publishing company in the Midwest in 1913. For reasons unexplained, Micheaux published the novel anonymously. It features protagonist, Oscar Deveraux, a homesteader in South Dakota who falls in love with a White woman. He ultimately elects to marry a Black woman, with whom he has a miserable union, and also has an unscrupulous father-in-law who cheats him of his property. Micheaux also describes in The Conquest the lack of opportunities for Black advancement in the cities and promotes the values of hard work, property investment and entrepreneurship. Micheaux personally sold his novel door-to-door, garnering over 1,000 sales, especially in the southern states. His second novel, The Forged Note: A Romance of a Darker Race, was published in 1915.

In 1917, his third novel, The Homesteader, was published. Like his previous works, it is inspired by his personal experiences. It also contains similar themes of adventure, betrayal, romance of interracial love and the experience of being Black in a White-dominated environment in a rural setting of South Dakota. However, in this novel, the Black wife, Orlean, of the Black homesteader, Jean Baptiste, commits suicide after murdering her wicked and greedy father, McCarthy, for ruining her marriage. Saddened, Baptiste is comforted by a White woman, Agnes, with whom he was formerly in love. He soon discovers that Agnes was actually of mixed heritage. Because she is actually a mulatto with African heritage, Baptiste can marry her and they build a happy life together. Utilizing the same approach as before, Micheaux personally peddles The Homesteader and the novel becomes a huge hit to Black readers.

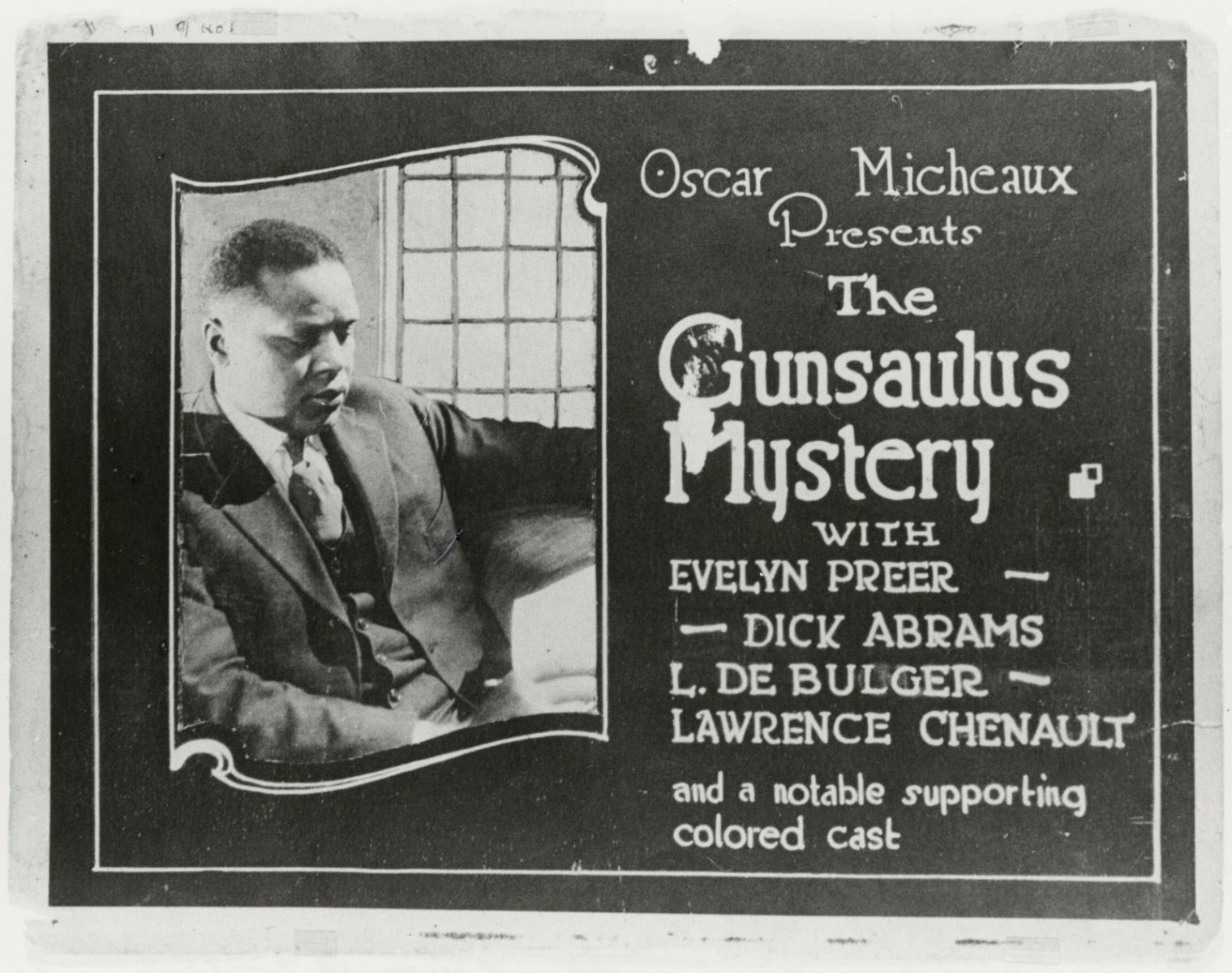

This great success led George Johnson of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company to approach Oscar Micheaux in 1918 to develop the novel into a feature film. Founded in Omaha, Nebraska in 1916 by the Johnson brothers, Noble (president) and George (manager), the Lincoln Motion Picture Company is known as the first all-Black movie production company and the first producer of “race” movies. Race movies were films circa 1915-1950s, that were Black-produced, starred a primarily Black cast and were geared toward a Black audience. This studio was different from many other motion picture companies at that time (and even to the present) in that it was Black-owned. The Lincoln Motion Picture Company relocated to Los Angeles in 1917 and it created five films, the final being, By Right of Birth (1921). Although the company operated only until 1923, it positively influenced the Black community and inspired Blacks to create and promote their own diverse interpretations of Black life.

Micheaux considered the offer to sell the rights to his novel but he had a clause: he would only sell if he could direct the film. The Johnsons refused his condition. The Lincoln Motion Picture Company chose not to collaborate because Micheaux had no prior experience in working with motion pictures, let alone directing a production. Although the potential of a joint production failed, the possibility of his novel becoming a film intrigued him. Having already dedicated The Homesteader novel to his personal hero, Booker T. Washington, Micheaux decided to adapt, produce and promote the film himself. He established the Micheaux Film and Book Company (with offices in Chicago, New York and Sioux City) and its first film project was The Homesteader.

(No copyright infringement intended).

He hit the road to sell stock in his film at $75-100 (USD) per share. He sold shares to his previous customers with whom he remained in contact from his time being a porter. He also solicited those who had bought his novels. When he met his budget’s needs, he began to shoot the film. In the article, “One-Man Show” in American Film, author Richard Gehr commented, “Thus began a pattern Micheaux followed for the next 30 years … He’d shoot a film in the spring and summer, edit it in the fall, then travel with a driver throughout the Northeast, South and East, where he would show stills of his stars to ghetto theater owners.” Micheaux’s personable demeanor and personal interactions endeared him to theatre owners, to the extent that often the theatre owners would advance him funds to develop his next film feature.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Though the film was protested by some Blacks because it overlooked and/or demeaned the life of Blacks in the city and in the Black church, The Homesteader was considered a groundbreaking triumph. Accordingly, Micheaux would continue to write, direct and produce more than 40 films in his career. From their inception, these films, created on a budget ranging between $10-20,000 (USD) were of inferior quality. Factors influencing the quality included the lack of well-trained actors; lack of continuity in plot development; subpar sound; overuse of simplistic set design; poor editing; and dim lighting.

The films of Oscar Micheaux dealt with topics of racism, colorism, classism, economic inequity, vice, violence, morality and Black self-improvement. As Gehr would also comment, “Micheaux’s novels and films constitute intriguing representations of key events in his life and times. The themes of interracial love, wrongful accusation and racial prejudice – both White versus Black and light-skinned versus dark-skinned Blacks – repeat themselves with an obsessiveness, verging on compulsion … Micheaux worked during a time when Blackness was still mysterious and threatening to most Whites … and this love-hate relationship expressed itself in all his work. For every film seeming to focus on alcohol, gambling and drugs, there was another celebrating Black achievement, and his analysis of racial politics still overwhelms all subsequent efforts.”

For all his flaws, Oscar Micheaux worked hard and diligently in creating his own lane in the film industry and there is no denying that he was a success. On March 20, 1926, he married Alice B. Russell, an African-American actress who would star in six of her husband’s films. Micheaux was able to create silent films despite his company going bankrupt during the Great Depression. With this economic crisis came a scarcity of resources, both for Micheaux to create his films and for potential theatregoers who could engage in entertainment activities. Adding to Micheaux’s woes was the new medium of sound films, known as “talkies”. He lacked any credible skill to initially transition from silent to sound films until Frank Schiffman, a theatre owner in Harlem, supported Micheaux’s reentry into motion picture production.

(No copyright infringement intended).

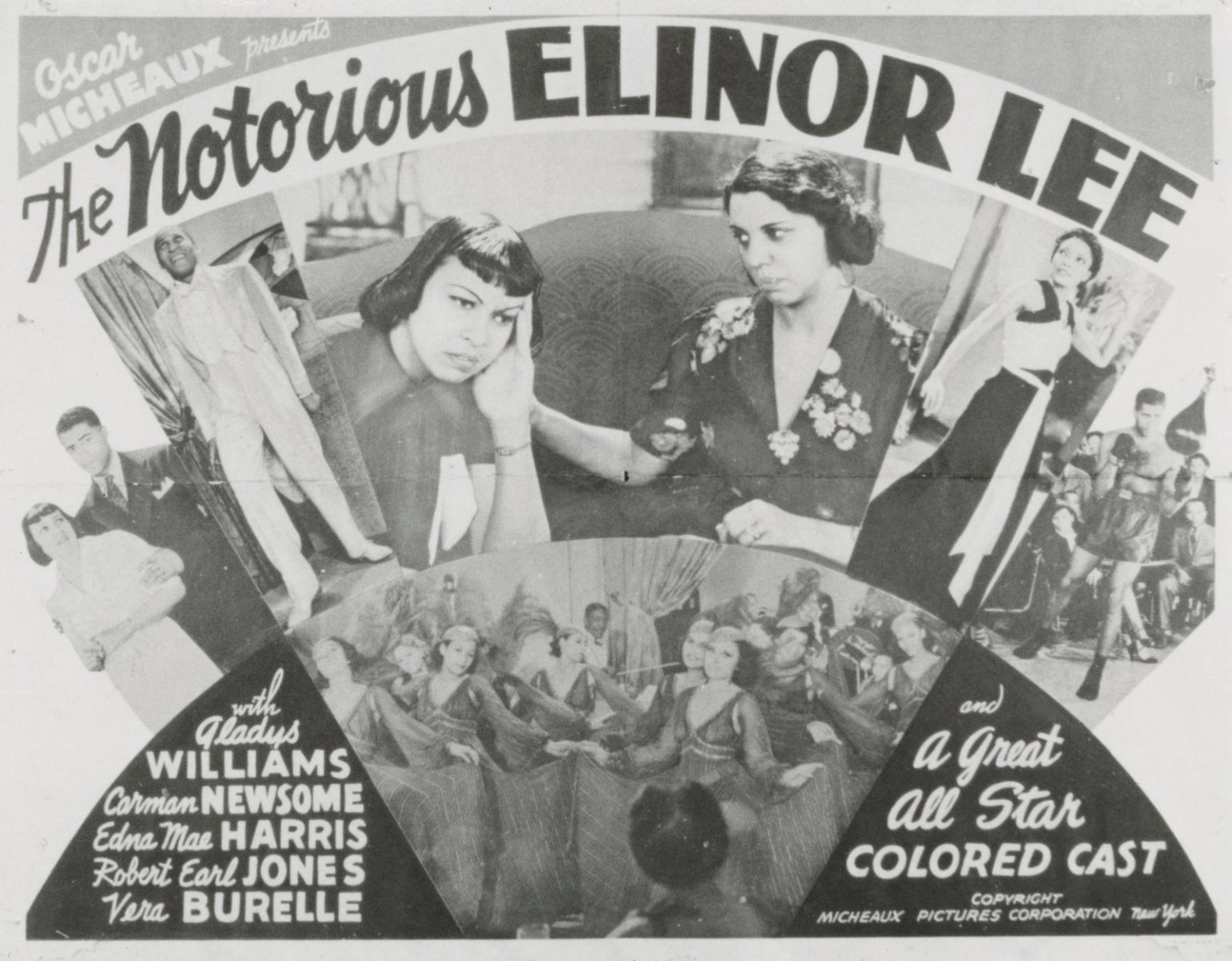

By the 1920s and 1930s, Micheaux had mastered several techniques of successful Hollywood film production, including providing a variety of genres such as mystery, action and drama. Another strategy that served him well was knowing his audience. He understood that White major motion picture stars had great social capital, which led to increased financial profits. Thus, he marketed the stars as his films as Black versions of the stars in “mainstream” films, e.g. Bee Freeman was marketed as “The sepia Mae West”; Ethel Moses as “the bronze Harlow” and Lorenzo Tucker was promoted as “The colored Valentino” during the silent films period and as “The colored William Powell” with the birth of the sound films era. Oscar Micheaux also provided opportunities of work and experience for Black actors that they may not have had otherwise. These actors included Robert Earl Jones, who starred in The Lying Lips (1939) and Notorious Elinor Lee (1940) and Paul Robeson, who, at 26 years old, made his debut in Body and Soul (1925).

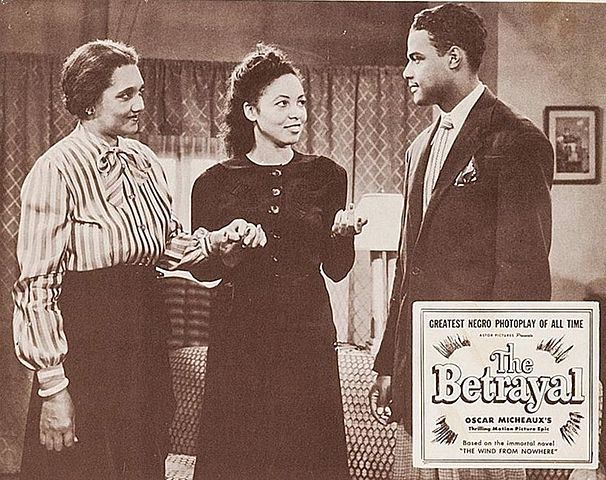

The last feature film of Micheaux was The Betrayal (1948) and though it played in mainstream theatres, it was not a success. After World War II ended, the liberalizing of the Hollywood film industry led to the decline of race films. Micheaux primarily devoted his time after that to writing and, due to crippling arthritis, speaking with audiences about his life, the materials he created, and the virtues of hard work and Black industry. Micheaux was preparing for one of these engagements when he passed away from heart failure on March 25th, 1951 in a hotel room in Charlotte, North Carolina.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Of his films, only several have survived intact. There are negative and positive comments about the Micheaux movies. Some comments described his films as derogatory, exacerbating racial stereotyping and intra-racial oppression. Journalist, J. Hoberman, in Film Comment, observed that the success of Oscar Micheaux as an independent Black businessman “… was as American as anyone – if not more so. Trapped in a ghetto, but unwilling or unable to directly confront America’s racism, Micheaux displaced his rage on his own people. In other words, part of the price that he paid for his Americanness was the internalization of American racial attitudes.”

Despite criticisms, the impact of Oscar Micheaux has been monumental and his legacy is undeniable, especially in the past several decades. As evidence of his legacy, the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame created in 1974 an annual award in salute to his accomplishments. Micheaux received in 1986 a star on the Walk of Fame in Hollywood (where he never produced a film) and was honored in 1989 with a Golden Jubilee Special Award by the Directors Guild of America. The Producers Guild of America created an annual award in his honor. In tribute to his work and influence, the Oscar Micheaux Society at Duke University was created and Gregory, South Dakota hosts an annual Oscar Micheaux Film Festival. Micheaux was identified by Afrocentric scholar and educator, Molefi Asante as one of 100 Greatest African-Americans and he was commemorated by the U.S. Postal Service with his own stamp in 2010. The discovery of prints of two of his silent Micheaux films, Within Our Gates (1919) in Spain and Symbol of the Unconquered (1920) in Belgium has further piqued interests. In 2014, Black filmmaker, Bayer Mack, and his film company, Block Starz Music Television, released Czar of Black Hollywood, a documentary about the life of Micheaux. In 2018, the internet and media company, The Mic, included Micheaux as one of fifty African-Americans who should be memorialized in the Black Monuments Project.

What was amazing about Oscar Micheaux was that, despite the social and economic obstacles of this country, he was able to create so prolifically. As Donald Bogle would assert in his pivotal Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films, “To appreciate Micheaux’s films, one must understand that he was moving as far as possible from Hollywood’s jesters and servants. He wanted to give his audience something ‘to further the race, not hinder it …’ [His works] remain a fascinating comment on Black social and political aspirations of the past. And the Micheaux ideal Negro worldview popped up in countless other race movies. His films likely set the pattern for race movies in general.”

I have always tried…to lay before the colored race a cross section of its own life, to view the colored heart from close range.

~ Oscar Micheaux