“I thank God for making me a man, but Delany thanks Him for making him a Black man.”

~ Abolitionist, orator, author and statesman, Frederick Douglass

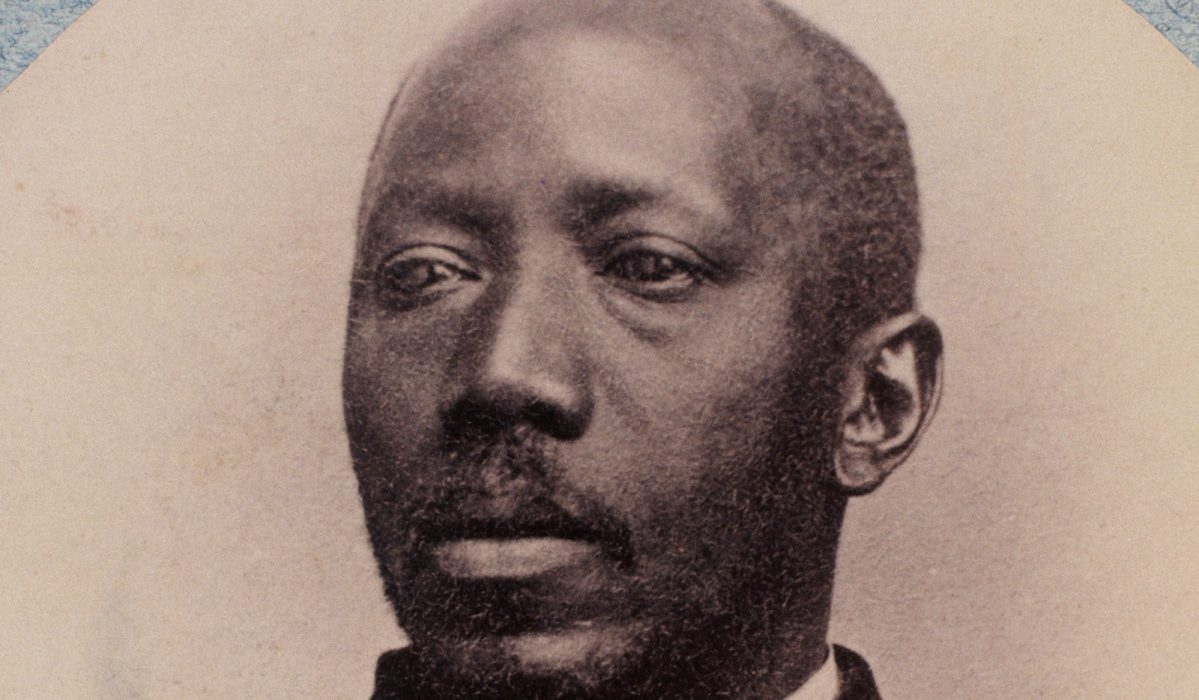

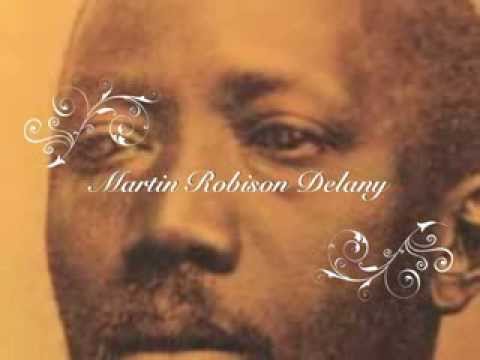

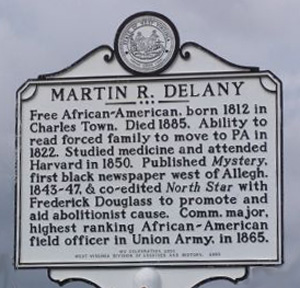

On May 6, 1812, in Charles Town, Virginia (presently located in West Virginia), a baby boy was welcomed by parents, Samuel and Pati Delany. Named “Martin Robison”, he was the youngest of five children. From family accounts, it is shared that the parents of both Samuel and Pati were directly from Africa and brought to America to be enslaved. It is said that Martin’s paternal grandfather had been a chief of the Gola in present-day Liberia. In Life and Services of Martin R. Delany by Frank A Collins, it is recorded, via oral accounts, that he escaped slavery by fleeing to Canada. Martin’s maternal grandparents were of the Mandingo/Mandinka in the Niger Valley. His grandfather was said to have been a prince and it is believed that this royal status influenced their slaveowner to, ultimately, free Martin’s grandparents. His grandfather returned to Africa and his grandmother remained with their daughter, Pati, in Virginia.

Virginia’s slave laws stated that the status of children were that of their mother; accordingly, the Delany children were not slaves, as Pati was free. Pati was exceptionally skilled as a seamstress and Samuel, who was enslaved, was an accomplished carpenter. After several attempts to enslave their children, coupled with threats of punishment because Pati was teaching her children to read and write from The New York Primer for Spelling and Reading, Pati and Samuel knew they had to leave the state. She and their children were able to quickly move and in 1822, settled in Chambersburg, a city in Pennsylvania, a free state. Samuel joined them the following year, as it took that long to purchase his own freedom.

Because schools for Blacks in Pennsylvania only went as high as elementary levels, Martin became an autodidact. In 1831, when he was nineteen years old, Delany walked 160 miles to live in Pittsburgh. In this bustling city, he attended a school for Blacks that was set up in Bethel A.M.E. Church, the oldest Black congregation in the city. Under the pastorate of Reverend Lewis Woodson, the school was funded by the African Education Society. Because so many Blacks had to work to support themselves and loved ones, classes were held in the evening. Delany later studied courses, including Latin and Greek, in a classical education at Jefferson College.

During his time in Pittsburgh, he worked during the day as a laborer and a barber. However, his life changed when he began an apprenticeship in 1833 with Dr. Andrew N. McDowell, a White physician and abolitionist. The previous year, a cholera breakout impacted the country. Delany learned the techniques of fire cupping and leeching, which were the modern practices used to treat many illnesses of that era. He continued to study medicine under the guidance of abolitionist physicians, including Dr. F. Julius LeMoyne and Dr. Joseph P. Gazzam, and later opened his own successful medical practice in Pittsburgh.

As a member of his new urban community, he quickly became active in abolition and civil rights, causes critical to the life and advancement of him and other Blacks. He attended National Negro Conventions; led the Vigilance Committee, which aided enslaved persons who were fugitives; and, according to his biography at Pennsylvania Civil War 150 site, helped “form the Young Men’s Literary and Moral Reform Society, which eventually turned into the Philanthropic Society as its activism increased.” He also served with a racially-integrated militia which was organized to defend the Black community from attacks by racist, White lynch mobs. In 1837, Delany signed a resolution that supported the suffrage of African-American men in Pennsylvania; it, tragically, was defeated and Blacks were stripped of their voting rights until 1871.

He began to travel throughout the Midwest and South, including Arkansas and Louisiana, practicing medicine and teaching abolition. In 1843, two events further influenced his life. Martin married Catherine Richards, the daughter of Charles Richards, an affluent merchant and landowner. Their union was blessed with eleven children.

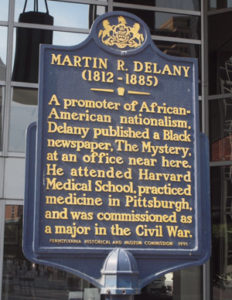

That same year, Delany founded The Mystery, the first African-American newspaper published west of the Allegheny Mountains. In his weekly newspaper, topics, notably abolition, civil rights, community engagement and political involvement, integral to Black advancement, were discussed. The Mystery was widely respected for its excellent content, and it was even common for its articles to be carried in White newspapers.

Not long after reporting on the Pittsburgh Fire of 1845, Delany was sued for libel by Fiddler Johnson. Delany had accused Johnson, an African-American man, of assisting slavecatchers in the city. The following year, Delany was found guilty and fined $650.00 ($22,000 in 2020). His colleagues in journalism and the abolitionist community assisted him in paying the fine and he sold The Mystery to the African Methodist Church, who published it as the Christian Recorder.

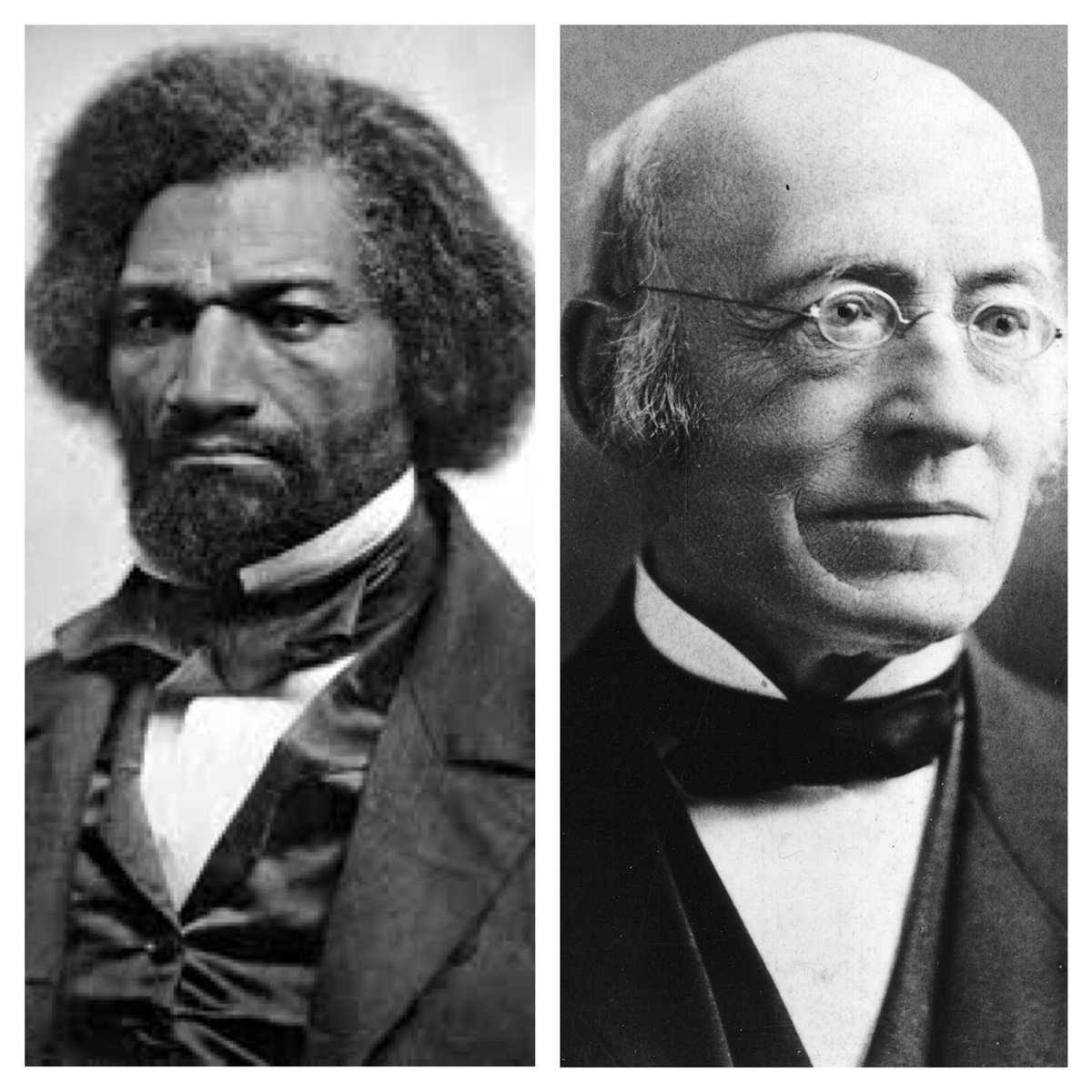

In 1847, Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, a White abolitionist, journalist, and editor of The Liberator, met with Martin Delany in Pittsburgh while on an anti-slavery tour. Douglass and Garrison would part ways later that year due to different views regarding the use of violence in abolition. Douglass advocated for political agitation while Garrison, a pacifist, believed that violence would likely have to occur to end slavery. Also impacting their parting of ways was Douglass’ belief that only African-Americans should be involved with an African-American newspaper.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Delany and Douglass began to plan their own publication and in late 1847, the North Star was launched. This newspaper, named after the astronomical object that many enslaved persons followed to freedom, shared current events and ideas from the perspective of African-Americans. Based in Rochester, New York, where Douglass lived, Douglass dealt with editing, printing and publishing while Delany reported, lectured, edited and secured subscriptions. Disagreeing about the actions required to support abolition, Delany left the North Star five years later.

Meanwhile, Martin Delany resumed his medical studies to further his practice and in 1850, was one of three Black men accepted to Harvard Medical College; the other two men were Daniel Laing, Jr. and Isaac H. Snowden. Only one month into their learning, the three men were dismissed from the medical school, despite being respected and liked by many staff and students. One particular group protested the Black men’s enrollment, citing that though it was fine that Blacks wanted to advance, the group did not want them at Harvard. Enraged at the blatant racism and overt discrimination shown them, Delany returned to Pittsburgh, convinced that despite the initiative, industry and talents of Blacks, they will never be treated equally.

(No copyright infringement intended)/

Martin Delany continued to advocate for Black advancement and speak against racial segregation in organizations, including the Freemasons. He also began to espouse that African-Americans should begin to seek emigration to Africa, the Caribbean and/or other places in the Americas because the racism in the United States was so rampant. In 1852, he wrote and published The Condition, Elevation, Emigration and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States Politically Considered. This work was followed up the next year with The Origin and Objects of Ancient Freemasonry; Its Introduction into the United States and Legitimacy Among Colored Men.

For a brief period, Delany worked as a principal of a school but soon returned to practicing medicine. This return turned out to be essential when another epidemic of cholera struck in 1854. While many fled the city, Delany remained in Pittsburgh, aiding numerous people who suffered from the deadly infection.

Later the year, he and James Monroe Whitfield, an African-American poet and activist, led the National Emigration Convention in Cleveland, Ohio. There he continued his passionate promotion of emigration, delivering his fiery manifesto, “Political Destiny of the Colored Race on the American Continent”. Attended and voted on by Black activists, including numerous women, this convention is considered by many historians to be the foundation of Black nationalism.

In 1856, Martin and Catherine moved their family to Chatham, a province of Ontario, Canada, in hopes to escape the oppressive conditions they suffered in the United States. He continued to practice medicine and was active in assisting on the Underground Railroad during their near three-year stay. Similar to his work in Pittsburgh, he aided those formerly enslaved in the United States who had attained their freedom in Canada.

In 1858, Delany attend the Chatham Convention, where White abolitionist John Brown presented his Provisional Constitution. There, Brown also shared his plan to free those enslaved; this plan led to the raid on Harpers Ferry in late 1859. Although many Blacks, including Delany, began to distance themselves from Brown because of his increasingly militant tactics, Delany did support Brown’s stance.

Insurrection long appealed to Martin Delany. In 1859 and 1861, he published Blake, also known as The Huts of America: A Tale of the Mississippi Valley, the Southern United States and Cuba. This novel was serialized; a section of Part I was carried in The Anglo-African Magazine and the remaining section of Part I was printed in the Weekly Anglo African Magazine. Blake was written to provide another perspective, from a Black vantage, of slavery. In it, the protagonist, Henry Blake is an insurrectionist who travels transnationally to free those enslaved. Although Delany credited Harriet Beecher Stowe for her authentic portrayal of the cruelty of the Southern White slavocracy in her Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1855), he was offended at her showing of Blacks as passive and accepting. Although Blake, was never completed, contemporary scholars have lauded Delany’s work, celebrating his anthropological approach that arose from his own travels. Various aspects, ranging from descriptive geography and identity to Black Southern dialect and revolution, further cements Delany’s novel as pioneering.

In 1859, Martin Delany led an emigration commission to West Africa, including Liberia, the homeland of his paternal grandfather. Liberia was a colony that had been established by the American Colonization Society to relocate free Blacks to lands outside the United States. His nine-month travels were prompted by his vision to develop a new Black nation along the Niger River, which was the area from where his maternal grandparents originated. Although he was able to contract with eight chiefs of Abeokuta region to settle their unused land, the treaty was later voided due to warfare, opposition by White missionaries, failure of successful execution of emigration, and emergence of the Civil War in the United States.

Returning to America in 1860 to continue to work for emancipation, Martin Delany shifted his priority of Black emigration when in 1863 President Abraham Lincoln enacted the military draft. Delany, at 51 years old, began actively recruiting thousands of Black men in Connecticut, Ohio and Rhode Island to serve in the Union Army. Many of these enlisted, including Martin’s son, Toussaint L’Ouverture Delany, formed the newly-created United States Colored Troops. An estimated 180,000 Black men enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops, approximately ten percent of all who served in the Union Army. Delany acted as a surgeon.

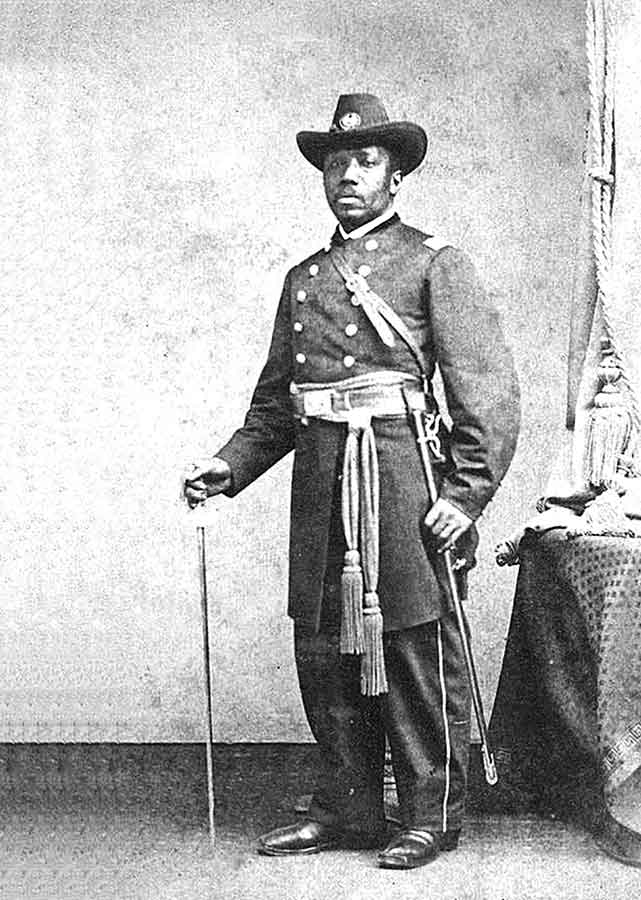

Proposing for a corp of Black soldiers to be commanded by Black officers, Martin Delany was granted a meeting with President Lincoln. Although a similar proposal of Frederick Douglass, Delany’s former collaborator and business partner, had been rejected by the government, Delany greatly impressed the nation’s leader. In February 1865, he was commissioned as a “Major”, rendering Martin Delany as both the first Black line field officer in the U.S. Army and the highest ranking African-American in the military during the Civil War.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Although he acted as a surgeon, his new rank led to a new assignment. Delany was sent to Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, where he recruited and organized formerly enslaved Blacks for work with the Union Army. His stationing in South Carolina was important because he wanted to lead his troops into Charleston, a capital city of secession. When the Union army captured Charleston, Delany was in attendance of the War Department ceremony, where Major General Robert Anderson presented the same flag that he was forced to lower four years prior when the Confederacy took control. Delany arrived at the ceremony with Robert Vesey, son of Denmark of the Vesey plantation. Denmark had been executed for leading a rebellion against slavery. The men arrived in the Planter, a Confederate ship. This armed ship had become Union property when African-American Robert Smalls, who had been enslaved, commandeered and piloted its 17 Black passengers through a Confederate blockade outside Charleston’s harbor from slavery to freedom.

With the end of the War in April and institution of Reconstruction, Delany was promoted as an official in the Freedmen’s Bureau. Under the pseudonym of “Frank A. Rollins”, he authored and published Life and Services of Martin R. Delany (1868). Although he was unsuccessful in some political runs, including for lieutenant governor as an Independent Republican in South Carolina and as Consul General to Liberia, he did serve on the Republican State Executive Committee and briefly as a trial judge in Charleston. In the latter position, he was suspiciously convicted in 1875 and briefly incarcerated for defrauding a church. Although he was pardoned by Governor Daniel Chamberlain (R), he was barred from resuming his position.

Martin Delany continued to actively support Black advancement, especially property and business ownership, having established his own land and brokerage business in 1871. He advocated for and aided Black farmers in improving their entrepreneur knowledge and negotiation skills for equitable pay. He supported the Freedman’s Bank, which had been run by Douglass. He continued promotion for involvement in the National Colored Conventions engagement. Most significantly, Delany relentlessly championed Black pride, nationalism, and civil rights.

He spoke out against Black political candidates, such as John Mercer Langston, an abolitionist, activist, attorney, educator and politician. Langston, a future diplomat and first president of what is currently known as Virginia State University, was the first dean of the law school at Howard University, a historically Black university. The reasons for Delany’s lack of support were that he felt these Black candidates were inexperienced or exploitative.

Ironically, he supported Wade Hampton, a racist former officer in the Confederate Army and politician of South Carolina. Delany was the only Black man of prominence in South Carolina to endorse Hampton, the candidate for the Democratic Party, in his 1876 bid for governor. Hampton won by less than 1,100 votes, partially due to Black swing votes influenced by Delany. Even worse, the election was replete with White intimidation and violence against Blacks, especially Black Republicans. Almost 200 Blacks were killed and numerous were assaulted in election-related violence. The “Red Shirts”, a paramilitary group of White male members of the Democratic Party and armed men from rifle clubs were heinous and permitted to act with little consequences. In 1876, an estimated 20,000 White men in South Carolina belonged to rifle clubs.

With Reconstruction ending in 1877, the Democrats, who now referred to themselves as “Redeemers”, had resumed control of the legislature in South Carolina. The Democrats, enforced by the Red Shirts and other similar groups, continued their drive to roll back any gains Blacks made during Reconstruction. At this point, Black Charlestonians began the discussion of emigration again.

To meet this end, the Liberian Exodus Joint Stock Steamship Company was formed in 1877 and Martin Delany chaired its finance committee. The following year, the company bought the Azor, a bark, for their forthcoming voyage. This voyage was led by Harrison N. Bouey, a minister and missionary who also served as the president of the voyage’s Board.

In 1879, he published his Principia of Ethnology: The Origins of Races and Color, with an Archeological Compendium and Egyptian Civilization, from Years of Careful Examination and Enquiry. In this book, he again campaigned for pride in Black cultural heritage as well as advocated race purity.

In 1880, Martin Delany left the Liberian Exodus Company to move to Boston and ultimately returned to Ohio. There, two of his children matriculated Wilberforce College (presently known as Wilberforce University), a historically Black institution of higher learning. Catherine already lived there, still working as a seamstress, and Martin returned to practicing medicine.

On January 24, 1885, Martin R. Delany passed away in Wilberforce, Ohio from tuberculosis; he was 72 years old. He is interred in a family plot at Massies Creek Cemetery in Cedarville, Ohio. His wife, Catherine, passed away in 1894 and she was laid next to him. Three of their children, Placido (1910), Faustin (1912) and Ethiopia (1920) are also buried alongside their parents. For more than 120 years, the family plot, including all the graves, were unmarked except for Martin’s. His site was designated by a government-issued tombstone on which his name was misspelled.

After years of fundraising, in 2006, the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center in Wilberforce, Ohio presented a monument in honor of Martin Delany and his family. Installed at the Delany family plot, this beautiful monument is constructed of black granite imported from Africa. It contains an engraved image of Delany in his formal military dress during the Civil War.

His legacy includes installation of a historical marker in both Pittsburgh and Chambersburg, Pennsylvania and a model of him at the From Slavery to Freedom exhibit in the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburg. In 2002, he was listed as one of the “100 Greatest African Americans” by Afrocentric scholar and author, Molefi Kete Asante. In 2017, the new bridge over the Shenandoah River carrying West Virginia Route 9 was named the “Major Martin Robison Delany Memorial Bridge”.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

According to Biography.com, Martin Delany was considered to be a “Renaissance Man: publisher, editor, author, doctor, orator, judge, U.S. Army major, political candidate and prison inmate … and the first African American to visit Africa as an explorer and entrepreneur.” Because he led such an expansive life, historian Paul Gilroy wrote, as cited on said website, “Delany is a figure of extraordinary complexity whose political trajectory through abolitionisms and emigrationisms, from Republicans to Democrats, dissolves any simple attempts to fix him as consistently either conservative or radical.”

“As men and equals, we demand every political right, privilege and position to which the Whites are eligible in the United States, and we will either attain to these, or accept nothing.”

~ Martin R. Delany