“Even after all the fame, farmer Junius G. kept working hard, kept loving his rich dark earth – likening the furrows his plows churned up to ‘chocolate waves.’”

~ Tonya Bolden, Author

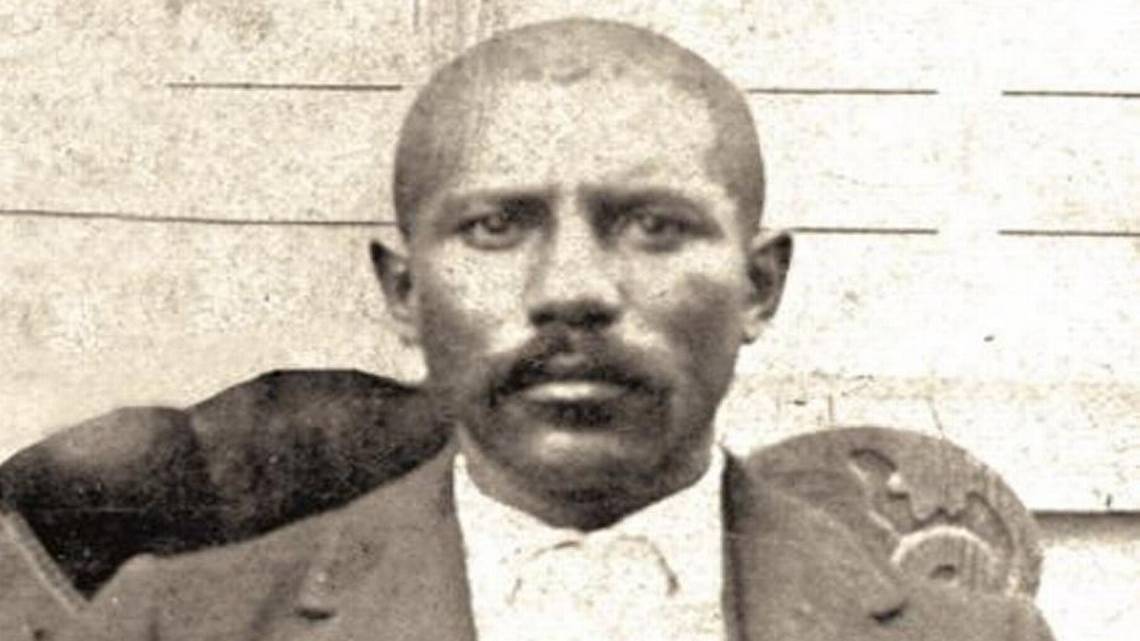

In a community near Greensburg, Kentucky, Martin and Mary Anderson Groves welcomed a baby boy into their family. He was the seventh of the nine children the Groves would have and they named him Junius George. Martin and Mary were married on the plantation of Alfred Anderson in October 1843 and the land tract was on the Green River’s Caney Fork. Anderson, a former U.S. Congressman, was one of the largest slaveholders in Kentucky. The parents were enslaved; Mary was owned by Anderson and Martin was owned by William Grove, who lived on a plantation near Anderson’s.

Because enslaved African-Americans were considered property, Alfred Anderson, in an early 1860s document, registered the birth of Junius George as May 13, 1858; however, contemporary resources state his birthday was April 12, 1859 and there is an article that quoted Junius stating that he was actually born in 1861.

In April 1865, Martin Grove, at forty-four years old, joined the U.S. Army and was a member of Company G of the 125th Regiment Infantry U.S. Colored Troops. In early May, he and several other members of his infantry died from eating pies that had been poisoned. On December 6th, the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, abolishing slavery.

Three years later, Mary began to receive a pension of $8 per month and Junius and four of his siblings were to receive $2 per month. She was to receive this amount until 1879 and the children were to be awarded this amount until they became sixteen years old. It is during this period that pension documents reveal “Grove” and “Groves” being used interchangeably. At some point, “Groves” is selected by Junius George as his last name.

Upon receiving emancipation, the Groves are committed to personal advancement and that included receiving public education during the three months that the rigors of farming lessened. However, Junius was primarily an autodidact and for the remainder of his life, Junius diligently read, studied and continued to learn. By 1870, Mary; her new husband, farmer, Henry Cox; Junius and several of his siblings settled in Haskinville, a small community in Green County.

In March 1879, at approximately twenty-years old, Junius G. Groves left Kentucky. With only $1.25 in his pocket, he was one of many African-Americans who left Kentucky, Tennessee and other states in the American South to settle in the West. This large migration of Blacks from areas along the Mississippi River to Kansas, known as the Exodus of 1879 or the Exoduster Movement, is considered the first mass movement of African-Americans after the Civil War. Many Exodusters selected to settle in the Sunflower State with the hopes of making their dreams come true. While some of these African-Americans were privileged enough to travel by train and steamboat, some came by oxcarts or wagons. Many, however, were like Junius, and had to walk. On his foot journey to Kansas, he worked jobs in various places of employment, including at a meatpacking warehouse, along the way to support himself.

Prosperous cities, such as Topeka and Kansas City, were attractive to Blacks as places for resettlement. Blacks also put stakes down in new towns, such as Nicodemus, and in burgs along the Kaw River (also called the Kansas River). It was in Armourdale of the Kaw Valley where Junius G. Groves secured a job on the potato farm of J.T. Williamson. There he labored for only $.40 per day, which were starvation wages!

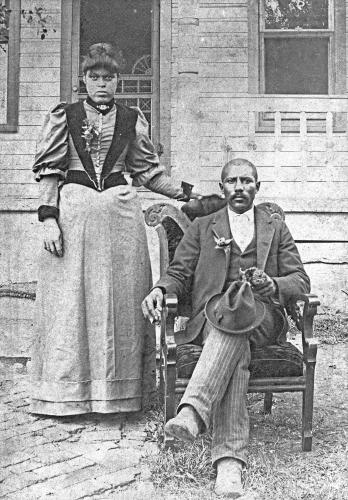

Before long, his consistent high quality of work and dedication prompted Williamson to give Groves a raise of, ultimately, to $1.25 per day. Groves was also promoted to be the foreman of Williamson’s farm. At this time, he met and began courting seventeen-year old Matilda E. Stewart, who hailed from Wellington, Missouri. On May 9, 1880, Junius and Matilda happily married. Their first child, Charles, was born the following year. The couple would have fourteen children; sadly, only twelve would live to adulthood. These children were Charles, Walter, Fred, Ora, Ida Mae, Lillian, Junius G. Jr., Sylvester, Etna, John, Cornelius and Theodore.

Despite these advances, Junius G. Groves knew he wanted more, especially his own land where he could farm for himself. Using his savings, he rented nine acres of land from Williamson. Groves traded a portion, or share, of his future crops with Williamson in exchange for his use of Williamson’s tools and team of mules. Groves was successful and was soon renting sixty-six acres of land, on which he grew potatoes. Matilda worked side by side with Junius on the land and shared his dream of owning their farm. They continued to constantly labor, even picking up additional jobs. They remained focused on saving every spare cent, foregoing any luxuries, and lived in a one-room shack.

(No copyright infringement intended).

By late 1884, the Groves had saved $2,200 and wanted to purchase eighty acres of land east of Edwardsville, not far from the mouth of the Kaw River. However, those acres cost $3,600. Junius entered into a deal with Ms. Rosanna Connor, an Indigenous American who owned the land. The land, at one time, was owned by people of the Kaw Nation. In fact, the word, “Topeka”, according to the Kansas Historical Society, is said to be of Kaw origin. Topeka, which is the name of Kansas’ capital city, means “a ripe and fertile area” or, in Groves’ instance, “a good place to grow potatoes”.

The Groves deal with Connor called for him to pay the total savings to her with the promise that the balance of $1, 400 be paid in a year. The Groves now had three children, Charles, Walter and Fred, and they were even more determined to make their dreams of independence and entrepreneurship manifest. Holding true to their agreement, Junius paid Connor for the land and in 1885, was the owner of eighty acres of fertile land!

Over the years, Junius G. Groves bought more land and continued to labor on it, growing potatoes. In 1891, the Historic Times, a newspaper in Lawrence, Kansas, reported that H. P. Ewing of Loring Kansas and Junius G. Groves were two of the wealthiest Black men in Kansas. In 1894, the Kansas Blackman, a Black newspaper, referred to him as the “Potato King of Wyandotte”, the county in which he lived. The following year, the Kansas State Agricultural Census recorded Groves as owning 400 acres in potatoes, 170 acres in apple trees, 160 acres of corn and 50 acres of cherry trees. He also owned 21 cows, 9 horses and 24 hogs.

His success allowed him to develop his own community, Groves Center; a church, Pleasant Hill Baptist Church; and a park, Groves Park. Author Tonya Bolden, in her No Small Potatoes: Junius G. Groves and his Kingdom in Kansas, described the park. She relayed that Groves Park in 1900, was revered, “… by Oshkosh Daily Northwestern as ‘one of the most picturesque spots in Wyandotte County.” That same year, the Indianapolis Recorder reported that Junius G. Groves is the “richest Black man living between the Missouri River and the Rockies.” Junius and Matilda promoted education to their children and his family lived in a fourteen-room home.

(No copyright infringement intended).

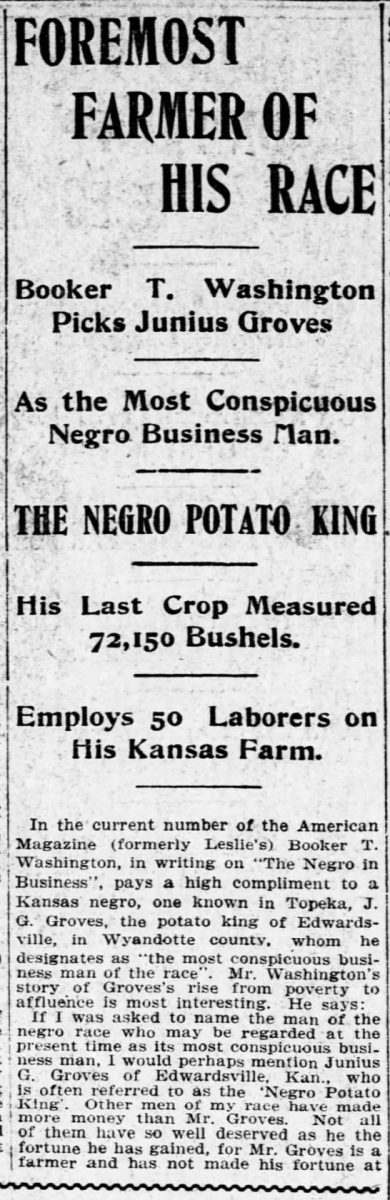

Junius G. Groves continued to be successful and in 1902, after being named by the Indianapolis Recorder as the “Potato King of Kansas” in 1900, he was hailed as the “Potato King of the World” in Helsinki, Finland! This honor, according to Bolden, was “bestowed upon him by the United States Department of Agriculture and presented by the Carnegie Steel Company.” In 1902, Groves had grown 72,150 bushels of potatoes. Because 1 bushel equals about 60 pounds and 1 pound equals about 3 potatoes, Junius G. Groves produced, respectively, approximately 4,000,000 pounds of potatoes or an estimated 12,000,000 potatoes!

Junius G. Groves grew so many potatoes that a special railroad spur to his potato house was constructed so that Union Pacific Railway could accommodate his business. Groves shipped his potatoes as well as other vegetables, including corn, cabbage and carrots, and fruit, including apples, throughout North America. Groves owned a grocery store, Cross Road Grocery Store, in Edwardsville. A passionate supporter of African-American advancement, he employed more than fifty laborers, most of them African-American, to work his land. In Groves Center, he sold parcels of land to African-American families. He also developed a golf course for African-Americans; this is possibly the first golf course in the United States established solely for African-Americans!

(No copyright infringement intended).

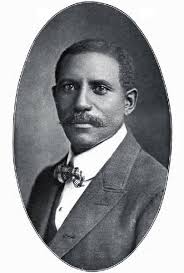

He was, according to the biography of Junius G. Groves written by Tisa M. Anders at BLACKPast website, “… elected secretary of the Kaw Valley Potato Association in 1890 and Vice President of the Sunflower State Agricultural Association in 1910 as well as a cofounder of both organizations in those years … [and] co-founded the State Negro Business League and later served as its President.” Groves also owned stock in banks throughout Kansas, in mines throughout Indian Territory and Mexico and, according to Anders’ biography at the aforementioned website, “… majority interest in the Kansas City Casket and Embalming Company.” Because of his many accomplishments and contributions, Groves was featured in The Negro in Business, authored by Booker T. Washington. Washington, president of Tuskegee University and advisor to several U.S. presidents, was a strong proponent of vocational education. In his book, Washington extolled the immense success, on a myriad of levels, of African-American farmer and businessman, Junius G. Groves.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1909, construction of a new, twenty-two room mansion was built on the Groves’ land. Although he sold eighty acres of his land in the Kaw Valley, by 1910, he still owned 523 acres of land. The sprawling home was constructed of red brick, trimmed in white stone, contained a roof of red tile and featured doors of oak. The home contained electricity, hot and cold running water and telephone service. Additionally, in the Groves’ home was a ballroom, which also served as a play palace for the Groves’ young children, and a library. Considered to be Junius’ favorite room, it contained countless books and booklets on the diverse aspects of farming. From the veranda, according to Bolden, Junius and Matilda could take in the picturesque view of the Kaw Valley kingdom they had built.

The love and value that Junius Groves had for his family was of paramount importance. Groves’ son, Charles, who was a 1904 graduate of Kansas State Agricultural College, served as the president of the Sunflower State Agricultural Association; Groves’ daughter, Ida Mae acted as secretary. In the article, “By the Sweat of His Face”, featured in the December 13, 1919 issue of The Country Gentleman, Groves asserted, “So here we are: every one of my boys a farmer; every one of my girls married to a farmer; every man and boy of them in overalls and working hard … I want these boys and girls of mine to stay on the land … I want my children and grandchildren always to be able to stand up and say: ‘We are a part and parcel of that army of farmers which feeds America!’”

It is this article that it is also reported that eleven sons and daughters lived on the farm. There were nine sons- and daughters-in-law and eight grandchildren. With the 500+ acres of land and an additional 1, 600 acres, on which grew wheat, in Gove County of northwest Kansas, Junius G. Groves greater ensured that there would always be enough land for the Groves’ descendants.

(No copyright infringement intended).

On August 17, 1925, Junius George Groves passed away from cardiac arrest. Because of the uncertainty of his birth year, most accounts simply state that he was in his mid-sixties. Almost five years to the day, Matilda E. Groves passed away on August 21, 1930; she was sixty-six years old. They are buried in Groves Cemetery, near Groves Center.

The life of Junius G. Groves remains honored. He was inducted, posthumously, into the Bruce W. Watkins Cultural Heritage Center Hall of Fame in Kansas City, Missouri. In 2007, his legacy was honored in Edwardsville, Kansas with the proclamation of establishing August 8th and 9th as “Junius Groves Days”. Celebrated by Groves’ descendants; the Vataw Colony Museum (which is dedicated to commemorating the Exodusters and their descendants); and the City of Edwardsville, the Junius Groves Days included a re-enactment of the deal made between Groves and the Union Pacific Railroad and the construction of the railroad spur to his property.

“It was pretty risky business paying out every dollar we had saved by five years’ hard work and close living and running ourselves $1,400 in debt, but we wanted a home of our own … and I know that I should succeed much better when I was tilling soil that I could call my own.”

~ Junius G. Groves