Originally called “Place des Nègres” and “Place Publique”, Congo Square is located inside Louis Armstrong Park of New Orleans, Louisiana. This open space, north of the French Quarter, is situated in Faubourg Tremé, a community where, historically, persons of African descent have resided for more three centuries.

During this time, the area, also known as “Circus Square” and “Place Congo”, became famous for representation and celebration of Africa Diaspora culture. This representation included the creation of African-American music, notably, jazz. As Nicholas Douglas quoted New Orleans native and jazz legend, Wynton Marsalis, in “Black History: Congo Square, New Orleans – The Heart of Music” in AFROPUNK, “Every strand of American music comes directly from Congo Square.”

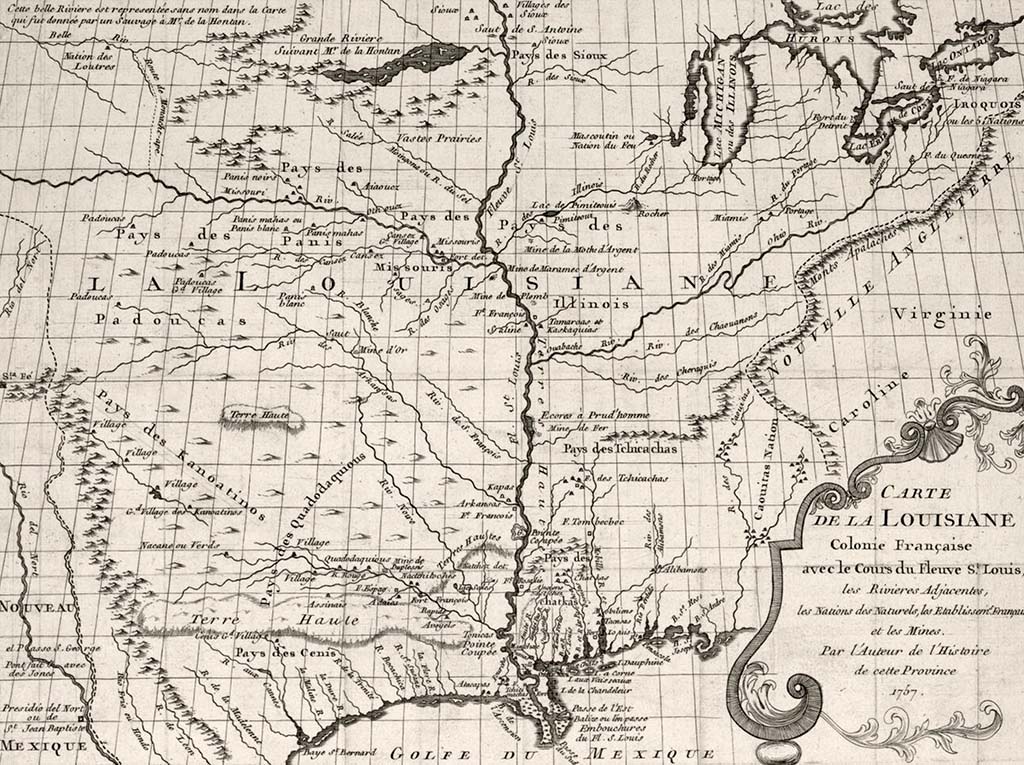

During European imperialism and colonialism, France and Spain were pressing, which included the enslavement of Africans, to become global empires. As such, their governance of territories included strict rules to define the relationship between colonists and those enslaved as well as cruel consequences when these rules were broken. Because Louisiana was a territory of France, in 1724, the European country enacted and strictly enforced the Code Noir, which translates to “slave code”. This code was sourced from the one that, in 1685, regulated colonies in the Caribbean that were controlled by France.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Containing fifty-four articles, the Code Noir “regulated the status of slaves and free Blacks, as well as relations between masters and slaves”, according to the article on the primary document, “Louisiana’s Code Noir”, published by BLACKPast. Among these articles were rules that centered upon Catholicism and they included the expulsion of persons who practiced Judaism; forced instruction of Catholicism upon enslaved Africans; allowance of only the Roman Catholic creed to be exercised; confiscation of persons of African descent who are directed or supervised by any person who is not a Catholic; and confiscation of any person of African descent who is made to work on Sundays and holidays, which are to be strictly observed.

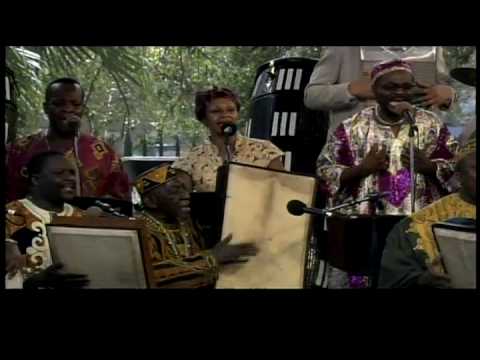

Because of this strict observation of Sundays and holidays being seen as holy days, enslaved persons used these days to gather together in both private, rural places, such as Bayou St. John and Lake Pontchartrain, and in public spaces including on the levees and in squares. In their gatherings, vestiges of their traditional African practices, including original languages, singing, call-and-response, dancing and drumming, were honored. Perhaps essential to these practices was the retention of vodoun, which was prohibited for enslaved persons of African descent throughout the rest of America.

Vodoun, or vodun, is commonly called “voodoo”. Vodoun, which means “spirit” or “God”, stems from the Fon people of Dahomey (presently known as Benin). The Fon, the Yoruba, the Kongo, and other ethnic groups of Africa as well as those of African descent on Saint Domingue (presently known as Ayiti in Haitian Creole or, commonly known as Haiti in French)) merged their cultures with those of the French. This merge, according to the submission of “Vodou” at Encyclopedia.com, was a combining of “… their African beliefs with Catholic lithographs, rites, and practices into a coherent whole. Slaves joined these various religious elements to create a belief system and worldview that constitute the core of Haitian vodou …” Despite the vilification of Vodoun, this African-based spiritual system, according to the reference submission, “… shares a common ethical denominator with other world religions – a strong sense of justice and service, respect for elders, beneficence, forbearance, and humanism. The notion of the unity of all forces of nature is central to Vodun. The connection between the living and the spirits, the Earth, the land, and various bodies of water is important in that all work together to seek balance and to restore harmony and rhythm.”

When Spain gained control of Louisiana in 1763, the severe strictness of the Code Noir was decreased. Those who were enslaved were allowed to set up a market where they could barter and sell their goods. They could even retain their monies in order to purchase freedom for themselves and, possibly, their loved ones. In the Douglas article, the author described coártacion, a process “… which established a court-arbitrated and legally binding price for a slave’s freedom (that) allowed slave entrepreneurs to buy their freedom and the freedom of family members.”

This “opportunity” to become free did not override the inherent right, as human beings, to naturally be free. This natural right to life, liberty and fraternity spurred the French Revolution in 1789. Lasting ten years, this rebellion demanded the abolishment, and execution, of the French monarchy. It also led to the development of a constitutional monarchy; the creation of a democratic republic excluded from religious influence; and the application of liberal ideologies and Enlightenment principles to structure society.

Two years after the French Revolution ignited, the Haitian Revolution began. From 1791 to 1804, enslaved persons of African descent and free persons of color fought against the French. Led by Toussaint L’Overture, the first Black general of the French Army, the Haitians valiantly defeated the armed forces of Napoleon Bonaparte after twelve years of battle. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the successor of L’Overture, declared the sovereignty of Haiti on January 1, 1804. The Republic of Haiti would adopt the same national tripartite motto of France, “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité.

With the success of the Haitian Revolution, Haiti made global history:

- The former colony was the first independent nation of the Caribbean and Latin America;

- As the second republic in the Americas, Haiti was the first country to abolish slavery; and

- Most significantly, Haiti is the only nation in history to be established by the successful revolt of enslaved persons!

As the Haitian Revolution was being fought, many Europeans, free persons of color and enslaved Africans fled Haiti and settled in New Orleans, doubling the population of the Crescent City. With their immigration into New Orleans came French, Caribbean and African influences.

Persons of African descent continued to practice and celebrate in Congo Square even after the United States gained the southern territory from France with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. However, the United States, with its patriarchal, White, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant heritage, attempted to decimate any Africanisms, including identity, traditions, language, spiritual systems, arts, even music, especially drumming. Because Louisiana Creoles were more accommodating, many aspects of African culture were retained in the southern state and this unique retention is practically exclusive to New Orleans. Additionally, Black and colored women in Louisiana held positions of power in Vodoun and society. Because of this, they were essential to the activities and practices in Congo Square.

In 1817, a city ordinance was passed that designated enslaved Africans could only congregate at “the back of town”, located off Rampart Street in the French Quarter; the area became known as “Congo Square”. There, they would continue to meet for socialization, development of open markets and practice of their traditional African ways. However, it should be noted that the vodoun practiced in this public square was and is more entertainment-based, as the actual rituals of this African-based spiritual system are most often practiced privately.

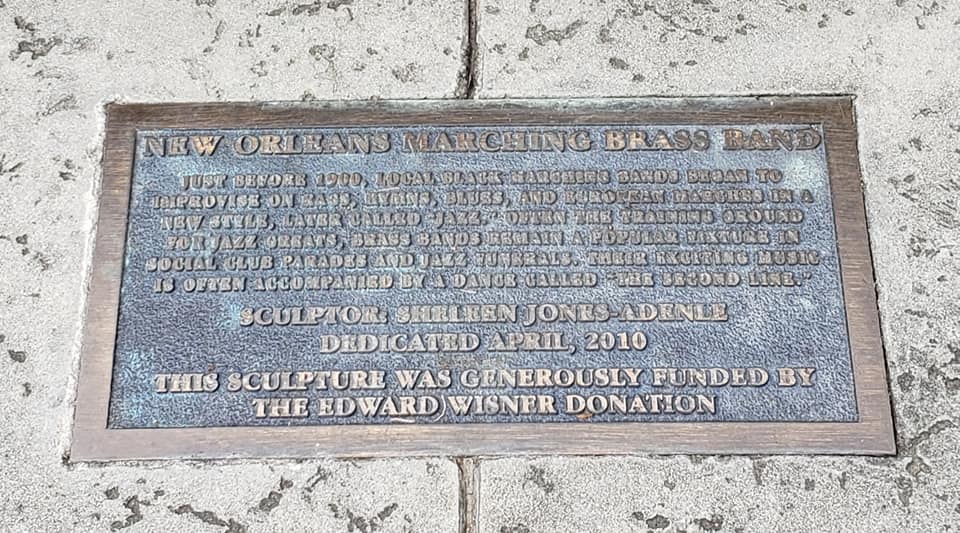

By 1840, the African traditions, including dancing and music, drew thousands of visitors to New Orleans. Congo Square was one of the city’s greatest attractions. Guests back then (and now) could move to the rhythms of the bamboulas, djembes and banzas and view dances such as the Calinda, Juba and Congo. These activities laid the foundation for events, such as second lines, Mardi Gras Indians parades and jazz funerals, unique to New Orleans. In the AFROPUNK article, Douglas describes the immense contributions, writing “Free people of color in New Orleans produced generations of musicians and musical families. These families lived around Congo Square and contributed their energy and vigor to the heartbeat of the musical tradition forming in New Orleans. While many musicians learned classical music, these same musicians were influenced by the rhythms and music they heard each Sunday coming from Congo Square.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Although the gatherings at Congo Square began to decrease by the time The Civil War began, social clubs and musical clubs were covertly created by free people of color to meet their particular needs. When New Orleans was captured by the Union Army, the rights of free persons of color became greater protected. With this protection came promotion of activities previously practiced, including those of dance and music at Congo Square.

By the 1880s, Congo Square became a popular site for Creole brass bands to perform jazz. In an attempt to further promote White dominance and squash Blacks’ cultural heritage, the public place was renamed “Beauregard Square”, in salute to Confederate general, P.G.T. Beauregard, in 1893. Born in St. Bernard Parish, he led his troops at the Battle of Fort Sumter. However, residents of New Orleans continued to call it Congo Square.

Because of its location on the Mississippi River, music from New Orleans, significantly Congo Square, greatly impacted the United States, Haiti, Cuba and Mexico. The creation of jazz played an integral part in the development of many urban areas, including Harlem, Chicago, Kansas City and Havana. By the 1920s, jazz performed by artists such as Charles “Buddy” Bolden, Joseph “King” Oliver, Edward “Kid” Ory, Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong and his wife, Lil Hardin, Honoré Dutrey, “Bunk” Johnson, Alcide Pavageau, Ferdinand “Jelly Roll Morton” LaMothe and Sidney Bechet, became all the rage. Within twenty years, this unique music would be heard the world over.

Unfortunately, many were displaced and daily life was interrupted for residents of the Tremé community when the New Orleans Municipal Auditorium was constructed at the back of Congo Square. Opening in 1930, this auditorium is the site of most Mardi Gras krew parades. In the 1960s, an urban renewal project further devastated land within Faubourg Tremé and in 1970, the City of New Orleans developed the land into Louis Armstrong Park. That year, the City began hosting events, including the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, annually at Congo Square. The festival grew in such popularity that a larger space was needed and it was moved to the New Orleans Fairgrounds.

In 1993, this site was added to the National Registry of Historic Places. In 2011, a city ordinance was passed by the New Orleans City Council to officially restore the traditional name of the public site to “Congo Square”.

Many musicians, including those previously mentioned, and contemporary artists, such as Antoine “Fats” Domino, Kermit Ruffins, Terence Blanchard, Trombone Shorty, Jon Batiste, Mannie Fresh, Juvenile, Lil’ Wayne and Tank and the Bangas hail from New Orleans. Legacy has been pivotal to the endurance of these music forms and popular families of New Orleans include the Marsalis, the Neville Brothers, the Pavageau and of Master P. Numerous music genres, from spirituals, opera, classical and labor songs to soul, blues, hip-hop and Afro-punk, have been impacted by Congo Square.

Congo Square has influenced several creations, including an essay, “The Dance in Place Congo” written by George W. Cable in 1896. The essay contained elements of African music. It inspired Henry F. Gilbert, in 1908, to compose a poem and the Metropolitan Opera of New York City to produce, in 1918, a ballet, both of the same name.

There are music pieces named “Congo Square” in honor of this site’s immense importance. These pieces include a traditional jazz version written and recorded by Johnny Wiggs; another jazz version by Sonny Landreth; a hard rock song by the group, Great White; and an R & B track (which is also the album’s title) by Teena Marie. “Congo”, a neo-soul song by Amel Larrieux and “Ghost of Congo Square”, the first track of Blanchard’s album, A Tale of God’s Will (A Requiem for Katrina) were inspired by the historic site. An African-themed jazz score created by Marsalis and Ghanaian Yacub Addy was entitled “Congo Square”.

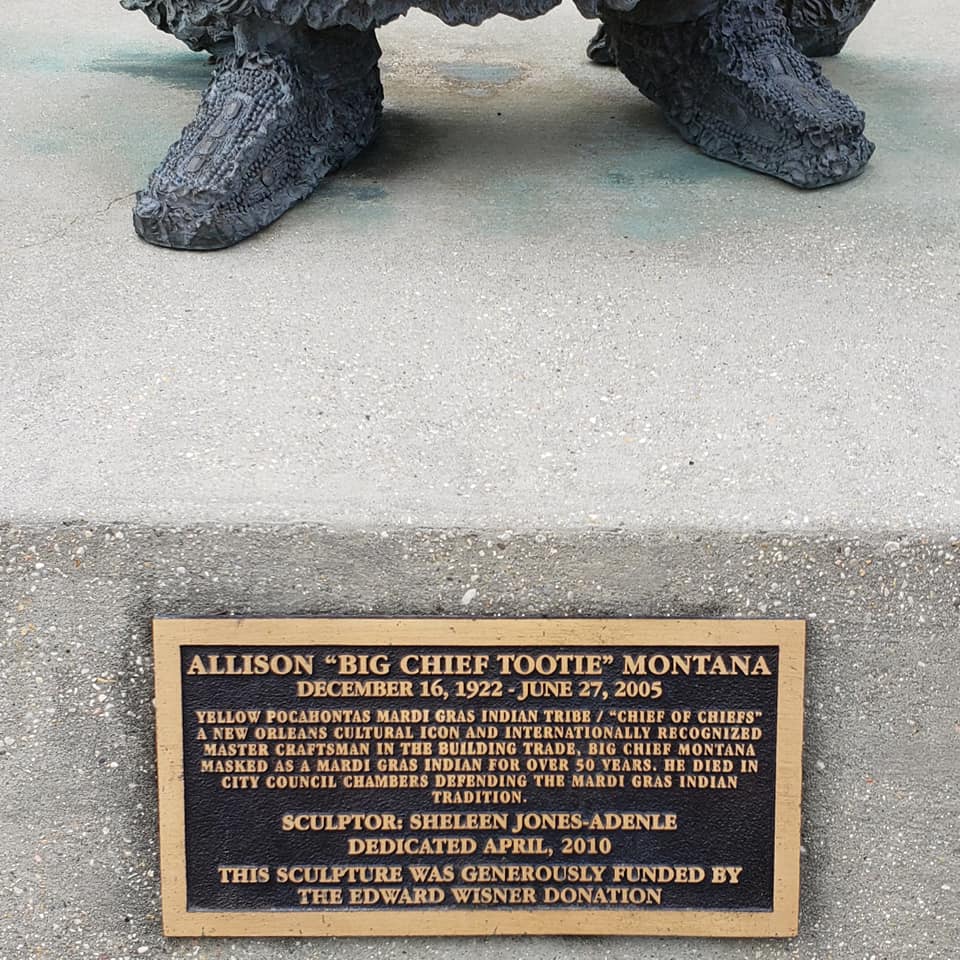

Congo Square can be seen in the HBO series, Tremé, which highlighted the lives of New Orleans residents after Hurricane Katrina. The importance of the African-based rhythms, traditions, practices and customs, from the promotion of jazz to the preservation of Black Indian cultures, can be experienced. In particular, one group, Donald Harrison, Jr. and The Congo Square Nation, has been featured on the acclaimed cable television series. Integral to New Orleans culture, Harrison is the Big Chief of the Congo Nation Afro-New Orleans Cultural Group. He learned secret rituals and his patterns of drumming, unique to his nation, from his father, Donald Harrison, Sr., who served as Big Chief of four nations. Harrison, Jr.’s albums, Indian Blues and Spirits of Congo Square, are classics.

In a video interview on Congo Square, Harrison comments on how he considers the culture of Congo Square “Afro-New Orleans because it’s not pure African anymore … it has Native American elements and American elements that are unique to this country. So, it’s changed but the culture and traditions still survive.” Speaking on the survival and essentiality of the Afro-New Orleans culture, Big Chief Harrison shared, “It’s like thirty or forty tribes that continue … and we call it a secret warrior culture because many aspects of it are secret and the only way that it has survived is because it’s been kept a secret … because America has a way of infiltrating something and the people on the outside, usually because they have more money, dictate what it should be. But the only way that it will really survive is if the people on the outside don’t infiltrate. So, that’s why it’s a secret culture.”

Continuing to be a pivotal place to gather, whether for spiritual purposes, entertainment or social justice, Congo Square remains to be revered as the origin of New Orleans culture, including music, specifically, jazz. As Kristin Gisleson Palmer, a New Orleans councilwoman, declared in the NOLA City Council statement that announced the 2011 name restoration of Congo Square, “… Jazz is the only truly indigenous American art form, and arguably, its genesis was Congo Square, a true gift to the entire country and world.”