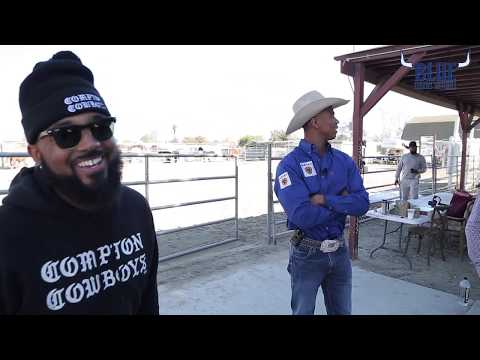

Located in the South Central area outside of Los Angeles, the Compton Cowboys is a collective of African-American friends who united to carry on the historical tradition of Black horsemanship. Their mission, according to their website, is to “uplift their community through horseback and farming lifestyle, all the while highlighting the rich legacy of African-Americans in equine and Western heritage.”

The many powerful and diverse contributions of African-Americans in the development of the American West, post-Reconstruction, has all too often been disregarded in, or worse, omitted from, history. While many African-Americans moved North and to the Midwest for better opportunities, still more moved West, settling in states, such as Kansas, Oklahoma and California. In their new homelands, Blacks became active in a myriad of professions, such as blacksmiths, business owners, educators, homesteaders, miners, physicians and ranchers. Perhaps the most often, thought-of image when considering a person who is synonymous with the West, though, is the cowboy.

For many, it is surprising, and often unsettling, when they, as adults, learn that one out of every four cowboys was Black, according to Paul W. Stewart, founder of the Black American West Museum and Heritage Center in Denver, Colorado. Additionally, there were approximately five thousand to eight thousand Black cowboys and cowgirls out West after Reconstruction, as stated by William Loren Katz in his The Black West: ADocumentary and Pictorial History of the African-American Role in the Westward Expansion of the United States. Author and journalist, Walter Thompson-Hernández spoke on the destructive impact this lack of knowledge had on him in his 2020 book, The Compton Cowboys: The New Generation of Cowboys in America’s Urban Heartland.

In “Compton’s Black Cowboys Ride to Reclaim Their Legacy” by Cristina Kim and Tonya Mosley posted on the website of WBUR, Thompson-Hernández recalled an experience of seeing a Black cowboy in the streets of Compton when he was a small child. The author, whose father is African-American and mother is Mexican, shared, “… I grew up seeing Mexican cowboys, a lot like Brown men on horses, was a normal thing … But also seeing Black men on horses, to me, was very important. That was a part of the story that wasn’t told to me in school, and I felt like it was a part of history that I would have wanted my teachers to have told me about — and it never was.”

As Thompson-Hernández became an adult, the Black cowboy symbolized the multitude of possibilities that he and other Black men could be in a society that often negated their mere presence, let alone, their accomplishments. This epiphany led to his research and personal involvement with the Compton Cowboys, which culminated in his recent book.

In The Compton Cowboys: The New Generation of Cowboys in America’s Urban Heartland, the journalist discussed the contemporary iteration of this union of ten urban Black cowboys and cowgirls whose ties with each other stem more than twenty years ago. Children then, they first met when they were members of the Compton Jr. Posse. This non-profit organization, according to Thompson-Hernández in his “For the Compton Cowboys, Horseback Riding Is a Legacy, and Protection” published in The New York Times, was “founded by Mayisha Akbar in Richland Farms, a semirural area in Compton that has been home to African-American horse riders since the mid-20th century.” These new members are building upon the vibrant legacy of the legendary Compton Cowboys, who first organized themselves more than thirty years ago. This new generation includes Roy-Keenan Abercrombia, 26; Kenneth Atkins, 26; Leighton BeReal, 28; Anthony Harris, 35; Charles Harris, 29; Carlton Hook, 28; Randy Hook, 28 and Lamontre Hosley, 23.

These cowboys all too clearly understand the negativity, such as gangs, poverty, police brutality and violence, that has permeated its city for more than four decades. Compton, historically, has been a city consistently ranked among those with the highest crime rates in the United States. The Compton Cowboys believe that horsemanship saved them and that it can save the next generation. Hook, who is the nephew of Akbar, discussed these facts in the Kim and Mosley article. He shared that life in Compton during the ‘80s and ‘90s was, “… anything you can name that will be wrong with the inner city community, like all happening at once, this is that era … It’s a lot of life threatening stuff out there. And having the horses back here allowed us, kept me, in the backyard as opposed to being in the front yard. And that’s a life or death decision.”

Thabisile Griffin, echoed Hook’s sentiment in The New York Times article, emphasizing, “The Compton Cowboys are a multigenerational story of Black people’s ability to survive and create alternate worlds in the face of neglect … Folks were frustrated, but subcultures of resistance persevered.”

This perseverance of the Compton Cowboys plays out in various forms, including providing weekly classes on caring of horses for children, at Richland Farm. An actual farm that spans eight blocks in an urban neighborhood, it is complete with stables and a running track. Richland Farm was actually owned by G.D. Compton, the city’s founder, during the 1800s.

Another form is their active pursuit to be involved on the Western rodeo circuit, which is predominately White. Aside from racism and discrimination, the Compton Cowboys also face other challenges including their dress code, the expensive costs of horsemanship and lack of access to essential resources such as healthy horses and saddles.

Aside from their obvious physical appearance, the attire of the Compton Cowboys challenges the traditional notion of what a cowboy looks like, even in these modern times. Anthony Harris enlightened readers of the Thompson-Hernández article that, “We’re different than most cowboys because we wear Air Jordan’s, Gucci belts and baseball hats while we ride … But we could also dress like other cowboys.”

Often their horses are bought at a relatively inexpensive cost due to factors, such as old age or trauma, at auction or they have simply been in the wild. As Hook championed in The New York Times article, “The throwaway horses that we were given ended up being the best horses for us because they had a feisty spirit and a chip on their shoulder just like we did … They were the underdogs just like we were.”

However, the Compton Cowboys believe that they and the horses are kindred spirits in that many in society have given up on them too. They use this principle in teaching others that come to Richland Farm about the power of healing and honoring life on their unique terms. The cowboys believe that educating and working with others to value another entity that breathes, that has feelings and emotions, with whom a bond can be developed and sustained, is literally life-saving.

Compton, similar to other cities that contain urban, Black cowboy communities throughout the United States, has recently been experiencing gentrification. This would be devastating for the cowboys, considering their history and present influence in their city. However, the Compton Cowboys hope to unify with their brethren in Philadelphia and Baltimore in order to further preserve and promote their rich legacy and positive way of life. As their motto heralds, “Streets Raised Us. Horses Saved Us.”

As such, the Compton Cowboys have been involved with several projects, including ale giant, Guinness; highlighted as topics of interest by Adidas, Boot Barn, Google and Playboy via YouTube; and recently worked in collaboration with the elite equestrian brand, Ariat.

At their website, Compton Cowboy merchandise can be purchased. Items include trucker style and beanie hats, tees, sweatshirt and prints. Walter Thompson-Hernández’s The Compton Cowboys: The New Generation of Cowboys in America’s Urban Heartland coffee table book and its amended version for young readers are also available for purchase. Additionally, one may make donations to their organization at their website as well as follow them on social media.

The Compton Cowboys, as per their website, are striving to illustrate that they “have firmly established themselves as one of the most dynamic groups in today’s generation.”

For greater enlightenment...

-

The Compton Cowboys: The community we’re searching for

-

Guinness: The Cowboys of Compton

-

How the Compton Cowboys Are Keeping Kids Off the Streets | The Daily Show

-

Ezekiel Mitchell Visits the Compton Cowboys | Episode 1

-

Riding Horses In The Hood With The Compton Cowboys

-

The Compton Cowboys' Impact Brings Kaley Cuoco To Tears

-

RESCUING HORSES AND HUMANS WITH THE COMPTON COWBOYS

-

The Compton Cowboys