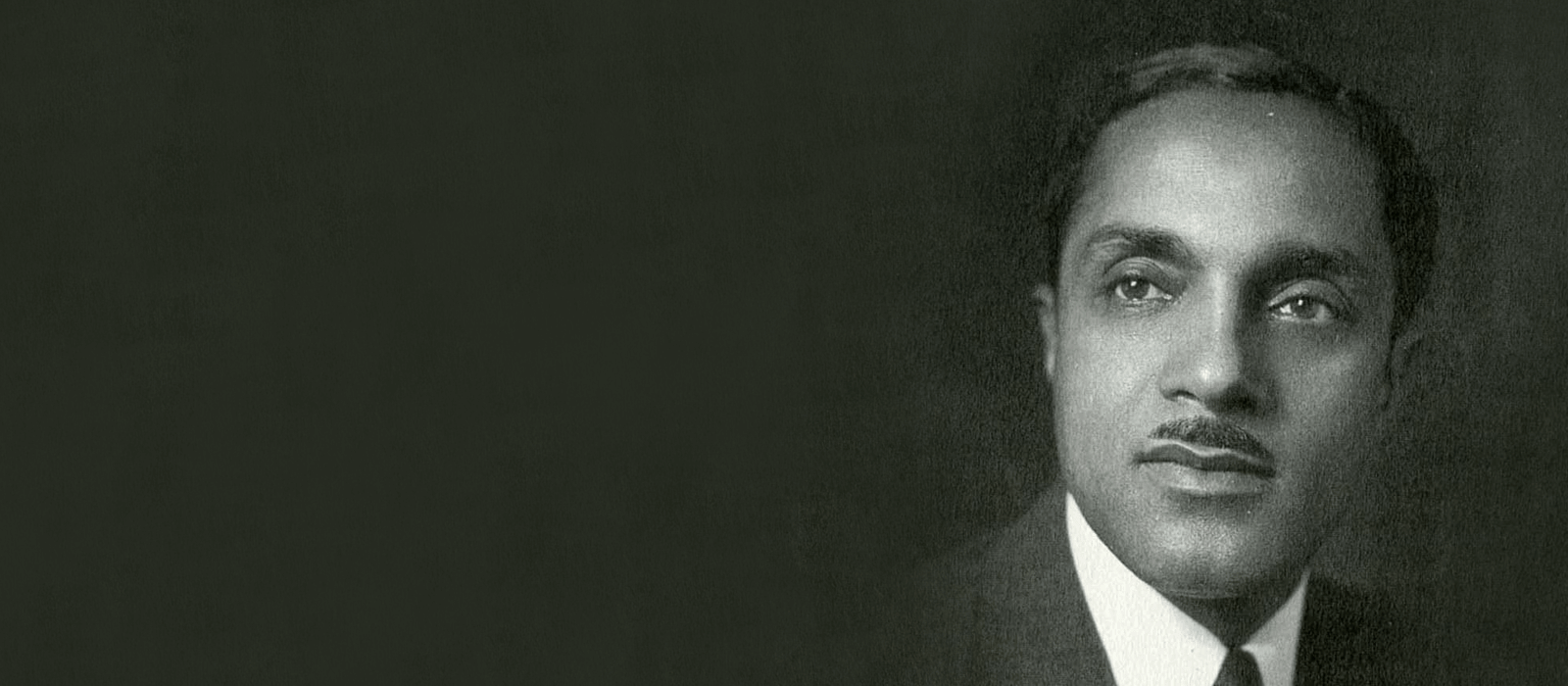

“Charles Harris Wesley was a legend in his own time … His deep concern that the pages of history should objectively reflect the contributions of Black folk to American civilization was monumental in its importance.”

~ James Cheek, President, Howard University

On December 2, 1891, Charles Harris Wesley was born to Charles Snowden and Mathilda Harris Wesley in Louisville, Kentucky. An exceptionally bright and industrious young man, he excelled in learning, to the extent that, in 1911, he graduated from Fisk University, a historically Black university, at the age of nineteen.

Upon graduating, he won a fellowship to study at Yale University. During this time, he worked as a server to supplement his academic pursuits. In 1913, Wesley earned a Master of Arts degree in history and was hired to instruct history and modern language as a member of the faculty at Howard University, another historically Black university, located in Washington, D.C. Wesley would serve on the faculty of Howard University from 1913 to 1942. His service at this institution of higher learning included acting as Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, 1937-38, and of the Graduate School from 1938-1942.

While at Howard University, two life-changing events occurred for Charles H. Wesley. In 1915, Wesley would marry Louise Johnson; they had one child, a daughter, Louise. Wesley also became great friends with Carter G. Woodson, who was the second African-American (after W.E.B. DuBois) to earn his doctorate from Harvard University. Woodson was the founder of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH; it is presently known as the Association for the Study of African-American Life – ASALH). Woodson’s organization was the largest, national organization of historians, educators, scholars and culture commentators on African-America.

Wesley began to collaborate with Carter G. Woodson, who was also the editor of the ASNLH publication, the Journal of Negro History, from 1916 to 1950. Woodson’s passion for Black history prompted him to strongly encourage Wesley to pursue a specialization in Black history. Wesley would heed Woodson’s advice and in 1920, was awarded a fellowship from Harvard University to further his academic studies. In 1925, Charles H. Wesley earned his PhD, becoming the third African-American to be awarded their doctorate degree from Harvard University.

This image is sourced from Pinterest

(No copyright infringement intended).

Wesley and Woodson’s personal friendship and professional connection extended into ASNLH, in which Wesley was heavily involved from 1916 to 1987. In the 1940s, Wesley assisted Woodson, working closely together on several research projects, and he was the co-editor of the Journal of Negro History during this time. According to Kate Meakin, who contributed the biography of Wesley to the BLACKPAST website, he also acted as co-author “… of updated editions of Woodson’s earlier works such as Negro Makers of History, The Story of the Negro Retold, and The Negro in Our History. These and other volumes carried the names of Woodson and Wesley as joint authors.” Upon the passing of Woodson in 1950, Wesley acted as the association’s Executive Director from 1965 to 1972, and later became its Executive Director Emeritus. He also became the editor of the Journal of Negro History until 1965. In 1936, Charles H. Wesley, building upon his research, including within ASNLH and at Howard University, co-founded the Association of Social Science Teachers at Negro Colleges.

Wesley’s active commitment to African-American interests extended beyond academia. From a spiritual vantage, Wesley was a devout Christian. As such, from 1914 to 1937, he was an active minister and presiding elder in the African Methodist Episcopalian Church. While pursuing his doctorate degree, Wesley often preached at Campbell AME Church and Ebenezer AME Church in Washington, D.C. During this time, he also was the presiding elder of all the AME churches in D.C.

This image is sourced from Ohio Memory

(No copyright infringement intended).

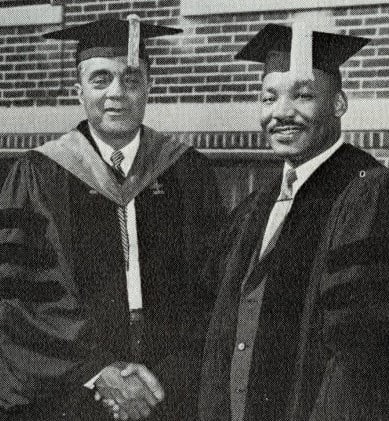

Charles H. Wesley was an active member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate, Greek-letter fraternity created by and for African-Americans. Wesley served as its 14th General President; he would lead in this role for five terms. He also worked as the fraternity’s National Historian for seventy years. In 1929, his book, The History of Alpha Phi Alpha, was published. As the fraternity’s historian, he also updated its following editions. Wesley was also an archon of Sigma Pi Phi fraternity, the oldest African American Greek letter fraternity and first of all the Black Greek-letter organizations; he also wrote material on its history and accomplishments. For his outstanding contributions, in 1953, he was awarded the Phi Beta Kappa Key. This award is given, as per its website, “to promote and advocate excellence in liberal arts and sciences”.

This image is sourced from Dayton’s African-American Heritage authored by Margaret E. Peters (No copyright infringement intended).

A member of several fraternal orders such as The Independent Order of Odd Fellows and The Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, Wesley was a Prince Hall Freemason (of Hiram Lodge No. 4 in Washington, D.C.) and a Sovereign Grand Inspector General (33rd Degree) of the United Supreme Council (Southern Jurisdiction, Prince Hall). He was also Grand Prior Emeritus of the United Supreme Council of the Scottish Rite, for which he was awarded the Scottish Rite Gold Medal Award in 1957.

In 1930, Charles H. Wesley, became one of the first African-Americans, significantly the first Black historian, to be awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1931, Wesley spent the year in London, England, studying emancipation of Blacks within the British empire, notably, the West Indies. During his time there, Wesley was in attendance at the founding of the League of Coloured Peoples. Founded by Harold Moody, a Jamaican-born, British physician and campaigner, the goal of the organization was racial equality. It was inspired by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the United States, of which Wesley was an active member.

During his lifetime, Charles H. Wesley authored numerous articles and twenty-four books in which he discussed a myriad of subjects integral to African-American life. His dissertation, Negro Labor in the United States 1850-1925, was published two years after his graduation from Harvard. Released while he was on faculty at Howard, Wesley’s book was a detailed and comprehensive study of African-Americans as laborers. This was markedly different from any other prior research on Blacks, as it dealt solely with slavery. In the Meakin biography article, she wrote that Wesley’s pioneering work “was written to challenge an array of false charges by earlier scholars that Black workers had limited abilities and aspirations. Wesley’s scholarship in this monograph and the others he wrote drew upon the best existing methods of survey research and historical documentation.”

Because of racial discrimination and segregation, many accomplished scholars in every field of endeavor sought employment and research opportunities at historically Black colleges and universities. Howard University would benefit enormously from this racial exclusion, rendering it to become one of the greatest institutions of Black scholarship. Charles H. Wesley was a tremendous asset in developing Howard University, including advocating for the election of Mordecai W. Johnson, the first African-American to become president of the university. Johnson, unanimously elected as the eleventh president of Howard University, served as the institution’s permanent head from 1926 to 1960.

Wesley’s meticulous and extensive research extended beyond African-American labor to include the involvement and contributions of Blacks during the Civil War and Black fraternal and professional organizations. In one of his works, The Collapse of the Confederacy, Wesley cemented, as per Bart Barnes in his article, “Charles H. Wesley Dies” of The Washington Post, his “expertise in Southern history and his scholarly articles on subjects, ranging from Black abolitionists to the diplomatic history of Haiti and Liberia, helped to legitimize and popularize the emerging discipline of Black history.” Wesley also proffered, according to Barnes, that “that the South’s loss in the Civil War was caused by internal social disintegration.” He wrote of accomplished Black men, such as Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and Prince Hall, an abolitionist, and founder of Prince Hall Freemasonry.

(No copyright infringement intended).

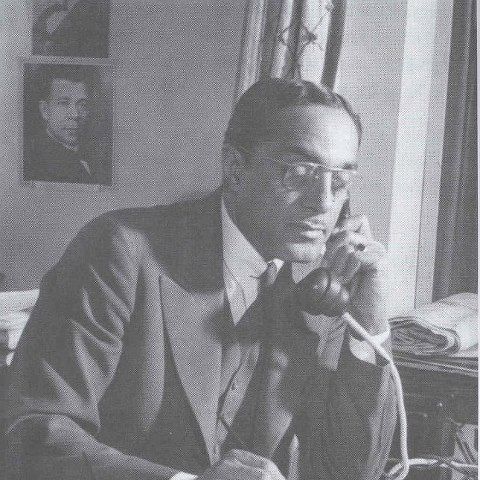

In 1942, Charles H. Wesley left Howard University, as he was elected to serve as President of Wilberforce University in Wilberforce, Ohio. Wilberforce University, a private, historically Black university, was supported by the AME Church. Wesley acted as its president until 1946. According to the “Charles Harris Wesley” summary of the Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History, in 1947, “church trustees, led by his former mentor Bishop Reverdy Ransom, dismissed Wesley. Student protests followed, and afterward, an acrimonious legal battle between the university and the state of Ohio, which provided funds for the School of Education.” Wilberforce University was divided into two institutions of higher learning and Wesley, in 1947, became the first president of Wilberforce State College (which, ultimately, became known as Central State University). As the president of the newly-created, state-funded, Black college, Wesley “upgraded the faculty, integrated the student body, and introduced new programs such as African Studies.” He remained as the president of the university until he retired in 1965. Sadly, during this time, his daughter, Louise, would pass away in 1950.

In 1965, Wesley returned to Washington, D.C. to teach history at Howard University. That same year, he stepped down from acting as the editor of the Journal of Negro History. Having served seven years as the Executive Director of ASALH, he would retire, again, in 1972. In 1973, his wife, Louise, died; she and Charles had been married for fifty-eight years.

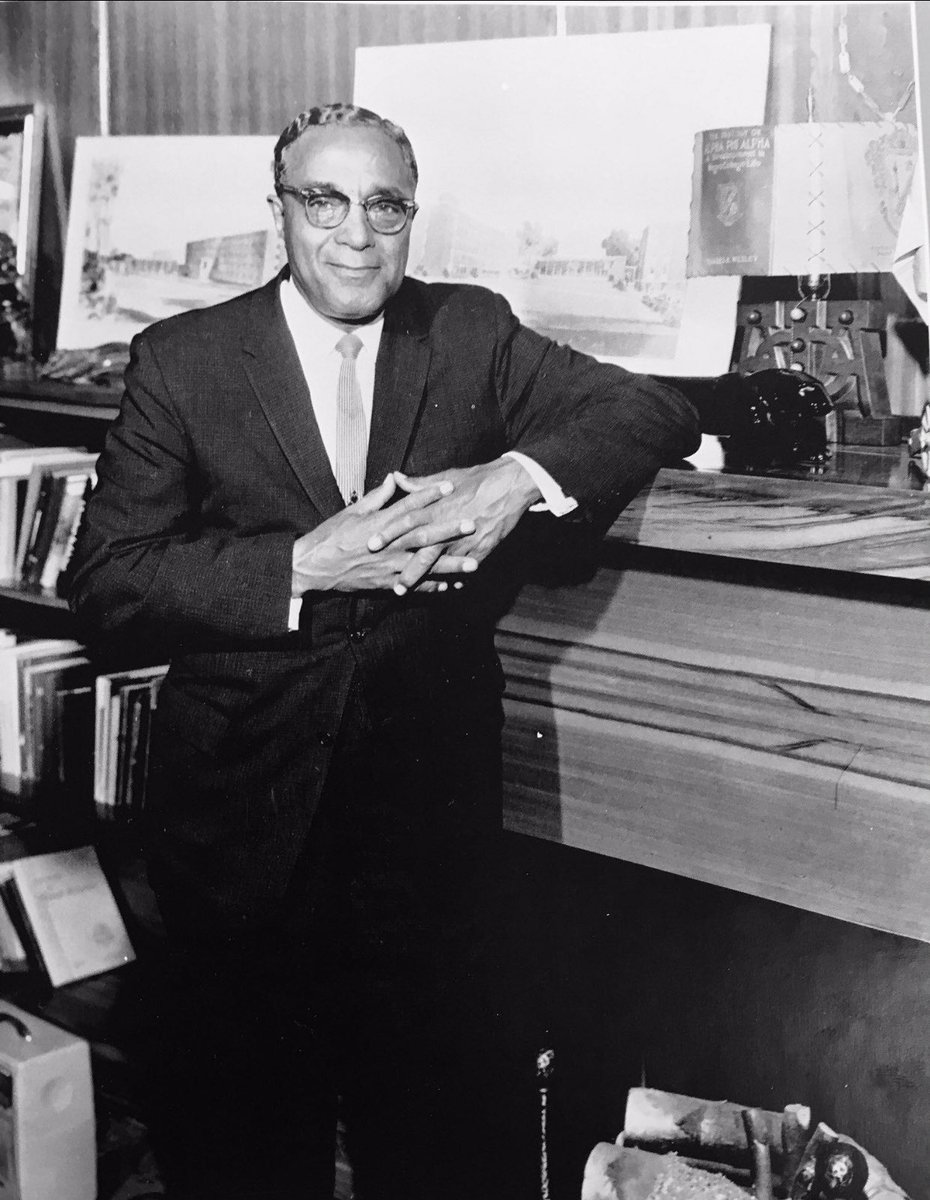

In 1974, Charles H. Wesley resumed his career, signing on as the founding director of the Afro-American Historical & Cultural Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. According to the entry, “African American Museum of Philadelphia: Charles H. Wesley of the African American Museum in Philadelphia” of the museum’s website, Wesley became involved with the institution because it “perfectly aligned with his desire to educate all Americans on the details of African American heritage … he realized its potential. In this role, he supervised the exhibitions’ designs, determined which objects would be displayed and generally prepared the Museum for opening.” On June 18, 1976, greater than 10,000 people attended the Museum’s opening celebration and grand opening. Wesley would retire not long after its opening, returning to Washington, D.C.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1979, Wesley married Dorothy B. Porter, an African-American librarian, bibliographer and curator who is perhaps best known for her development of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University into a premier research center. A widow, her late husband was James A. Porter, an African-American artist, educator and historian who established the scholarly field of African-American art.

After his retirement, Wesley continued to write and published his final book, The History of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs: A Legacy of Service, in 1984; he was ninety-two years old.

On August 16, 1987, Charles H. Wesley, at the age of ninety-five years old, died of pneumonia and cardiac arrest at Howard University Hospital in Washington, D.C. He was buried at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery, Suitland, Maryland.

The recipients of numerous accolades, honorary doctorates and awards, such as the Amistad Award, Charles H. Wesley was inducted into the Walk of Fame of the historic Wright-Dunbar District in Dayton, Ohio in 1996.