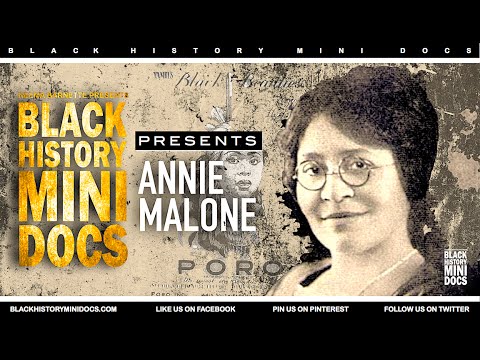

“Mrs. Malone’s legacy is a merging of women’s health and economic independence.”

~ John H. Whitfield, author, A Friend to All Mankind: Mrs. Annie Turnbo Malone and Poro College

On August 9, 1869, Robert and Isabella (née Cook) Turnbo welcomed the birth of their tenth child, Annie Minerva; she would be the second to the last of their eleven children. Her parents, who had been enslaved in Kentucky, found freedom in Metropolis, Illinois, where Annie was born on their farm.

Tragically, Annie became orphaned when she, at a young age, lost both of her parents. She moved to Peoria, where an older sister, Ada Moody, reared her. She loved learning, especially chemistry. However, she was constantly ill. Her illness caused her to miss a great deal of school, hindering her from graduating high school.

Typical of many young women, she was interested in caring for and styling her hair. However, the products and methods that African-Americans used at the ending of the nineteenth century were often harmful, even toxic, and damaged not only the hair but also the hair follicles and scalp of Blacks. These products often contained soap, butter, goose fat, bacon grease, even lye, in order to straighten the naturally coiled hair of many African-Americans. Adding to this damage was some African-Americans’ use of carding combs, which are for the detangling wool of sheep.

Many Black females saw their natural hair and styling in braids and plaits as reminiscent of slavery. According to the Freeman Institute website, which is dedicated to the memory of Annie Turnbo Malone, “the popular style among Black women was that of a ‘straight hair’ look. Black women were starting to turn their backs on the braided cornrow styles they’d associated with the fields of slavery and began to embrace a look which, for them meant, freedom and progression toward equality in America.”

While Annie Turnbo was out of school, she began practicing hairdressing techniques and creating her own mixtures to treat the hair of African-American women. By 1900, she and several of her siblings moved from Peoria to Lovejoy, Illinois. At twenty-years old, she had developed her own line of hair care and beauty products for Black women. Her products, which included oils, non-damaging hair relaxers and the hair stimulant, “Great Wonderful Hair Grower”, were carried in the local stores and sold door-to-door.

Turnbo moved to St. Louis, Missouri in 1902 because it was the fourth largest African-American populated city in the United States. The city was bustling, in preparation of the 1904 World’s Fair. Because she was a Black woman, Turnbo utilized unconventional methods at that time to promote her products. She hired and trained three assistants and all four solicited Turnbo’s products door-to-door, even giving away samples and providing hair treatments as well as on-the-spot demonstrations on how to best use the products. Turnbo also gave speeches from a buggy, advertised in Black newspapers, held press conferences and embarked on a sales tour of southern states. She even developed a process to purchase her products by mail-order!

In all these promotional activities, she continued to recruit and train Black women to sell her products. Turnbo believed that enhancement of African-American women’s physical beauty would lead to greater self-esteem and self-respect. It also could increase possibilities of success, including career choice and economic independence, in other aspects of their lives.

In 1902, Annie Turnbo married Nelson Pope and opened her first store, located at 2223 Market Street. Although the marriage failed, ending in divorce in 1907, the business was a phenomenal success. She opened her own salon and her products were sold throughout the Midwest.

She named and copyrighted, in 1906, her haircare and beauty products line, “Poro”. Her selection of the word, sourced from the Mende people in West Africa, served several purposes. According to the Freeman Institute site, Annie Turnbo “… called it Poro, a West African (Mende) male secret or devotional society — an organization located throughout Liberia and Sierra Leone dedicated to disciplining and enhancing the body spiritually and physically. There were some elements of the term that seem to indicate beauty. Even though it was not in vogue during that era, Annie wanted to connect her ‘Poro Agents’ to their African roots and this was her way of doing that. She and her assistants sold her unique brand of hair care products door to door.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

One of the agents was Sarah Breedlove, who later became known as Madam C.J. Walker when she started her own Black haircare and beauty products line. Breedlove worked in Denver, Colorado until she and Turnbo Malone parted ways because of a disagreement. Breedlove created, based upon Turnbo Malone’s formulas, her own brand of products; this prompted Turnbo Malone to copyright her products

Because of her continuous success, Turnbo moved to a larger facility on 3100 Pine Street in 1910. In 1914, Annie Turnbo married for a second time; her husband was Aaron Malone, a school principal and former Bible salesman. He became the president and chief manager of her company.

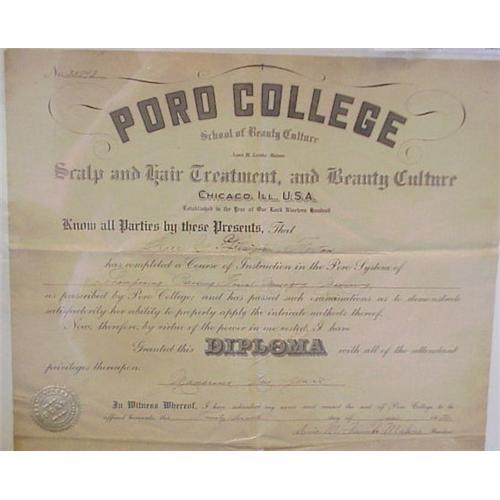

By this time, Annie was a millionaire and in 1917, had constructed Poro College, a five-story facility, in the historic, upper-middle class, Black neighborhood of “The Ville”. Poro College has the distinct honor of being the first educational institution in America dedicated to the study and practice of Black cosmetology.

Turnbo Malone’s facility was also the first of its kind. In the biography sketch of Annie Turnbo Malone of the historical archives of The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Poro College was “… a complex that included her business’ office, manufacturing operation and training center as well as facilities for civic, religious and social functions … served as a gathering place for the city’s African Americans, who were denied access to other entertainment and hospitality venues.

The complex, which was valued at more than $1 million, included classrooms, barber shops, laboratories, an [500-seat] auditorium, dining facilities, a theatre, gymnasium, chapel and a roof garden. Many local and national organizations, including the National Negro Business League, were housed in the facility or used it for business functions. The training center provided cosmetology and sales training for women interested in joining the Poro agent network. It also taught students how to walk, talk and behave in social situations. During the early 20th century, race improvement and positive self-image were seen as a way to increase social mobility. By teaching deportment, Malone believed she was helping African American women improve their standing in the community.”

By 1926, Poro College employed approximately two-hundred people and the school, ultimately, graduated more than 75,000 agents throughout the world, including in North America, Africa, South America and the Caribbean.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Annie Turnbo Malone was a highly successful entrepreneur whose wealth became prominently known. One of the first persons in Missouri to own a Rolls Royce, the Philadelphia Tribune reported that in 1923, Turnbo Malone paid the highest income tax of any African American in the country. An example of her wealth was her 1926 income tax payment totaled more than $40,000 (approximately $562,000 USD in 2019).

Despite her affluence, Annie Turnbo Malone lived conservatively. Her generosity in supporting her loved ones, her employees and agents as well as numerous Black charities, Black children’s homes, Black civic organizations and historically Black universities, such as Tuskegee Institute, made her one of the first major Black philanthropists in the United States.

Annie Turnbo Malone bought homes for her siblings and, though childless, she financed the education of her nieces and nephews. She awarded her employees with diamond rings for five years of service and gifted monies for opening savings accounts and purchasing homes. Turnbo Malone ensured that her employees and agents, all African American, were paid well and provided opportunities to advance.

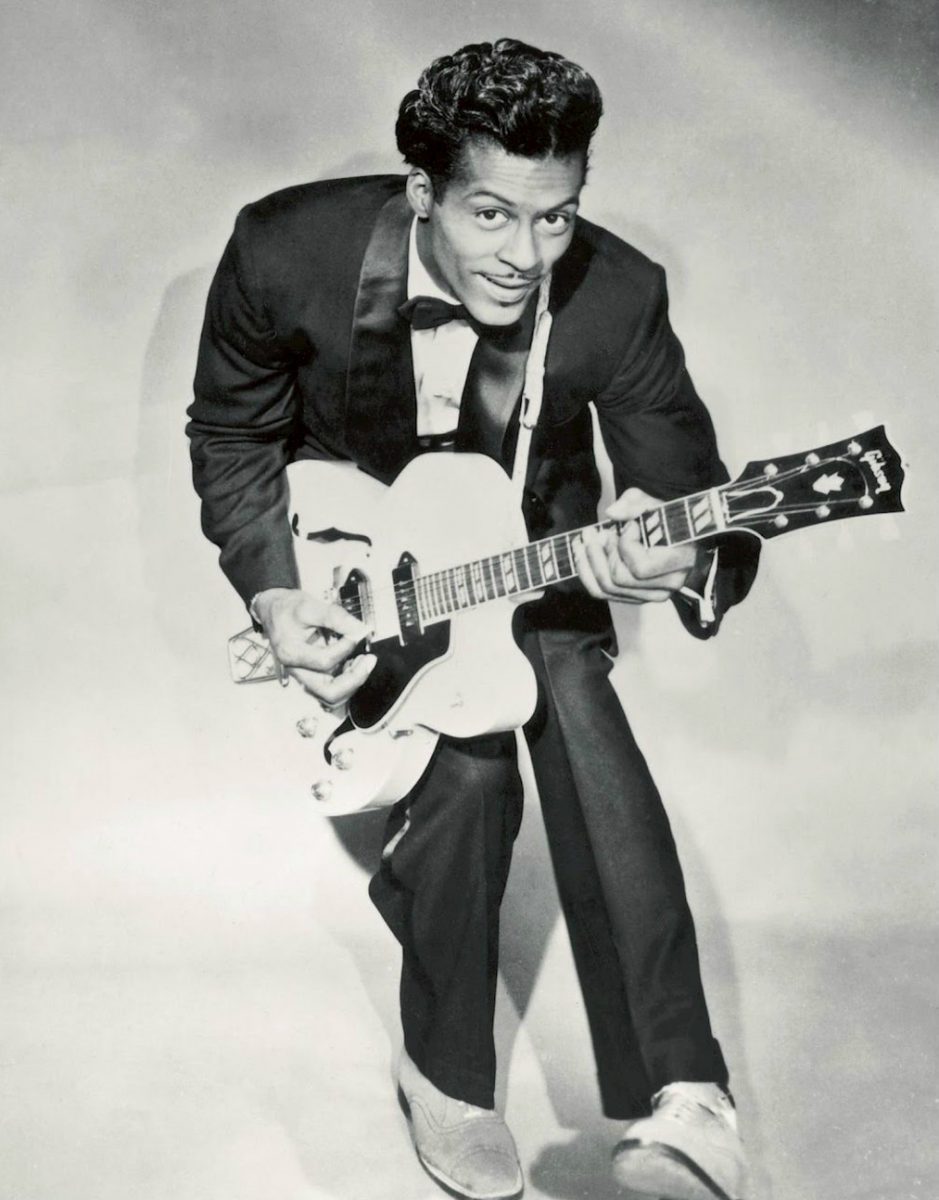

While Turnbo Malone’s system trained tens of thousands of women internationally, there were also men who were students at Poro College. One of these men was Chuck Berry, who became one of the greatest rock-n-roll legends in history. Following in the footsteps of his sisters, Thelma and Lucy, Berry trained as a beautician and graduated from Poro College in 1952. Chuck Berry was born in St. Louis and lived at 2520 Goode Street for the first several years of his life. One of his greatest hits, “Johnny B. Goode”, is spelled after the name of the street on which he lived. His home was one block away from the St. Louis Colored Orphans Home at 2612 Goode Street, of which Annie Turnbo Malone was integral in its founding and success.

and Poro graduate Chuck Berry, circa 1958

(No copyright infringement intended).

She donated $25,000 to build the St. Louis Colored Young Women’s Christian Association. She gifted the first $10,000 in 1919 (approximately $145,000 USD in 2019) to construct the new facility for the St. Louis Colored Orphans Home, of which she served as board president from 1919 to 1943. In 1922, the St. Louis Colored Orphans Home bought a facility at 2612 Good Avenue. The facility, upgraded and expanded, continues to serve “The Ville” neighborhood today. It was renamed the “Annie Malone Children and Family Service Center” in 1946 and Goode Avenue was renamed “Annie Malone Drive” in 1986, both in her honor.

According to the Freeman Institute website, Turnbo Malone was magnanimous with her support of Black institutions, financially and physically. It stated that, “During the 1920s, Malone’s philanthropy included financing the education of two full-time students in every historically black college and university in the country. Her $25,000 donation to Howard University was among the largest gifts the university had received by a private donor of African descent …”

Her personal wealth in the 1920s, according to Carol Brennan in Black Biography, was $14 million (approximately $175 million USD in 2019). Among the many organizations of which she was a member, Annie Turnbo Malone also served as president of the Colored Women’s Federated Club of St. Louis, was an executive member of the National Negro Business League and was an active member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

(No copyright infringement intended).

While working on charitable and civic activities, she often left the daily management of her business to her husband. In many ways, Aaron Malone was ill-equipped to manage the business affairs of Poro College, prompting Annie to resume running her business. From 1921 to 1927, they were engaged in a power struggle that became public knowledge when he filed for divorce, demanding ownership of half of her businesses. Many Black male leaders and politicians sided with Aaron Malone’s claims that he was the reason for the success of Poro.

However, countless Poro employees and agents; the Black press; charitable organization leaders; university administrators and civic leaders, including Mary McLeod Bethune, who was president of the National Association of Colored Women, sided with Annie Turnbo Malone. Her supporters readily attested to her character, leadership, service, commitment and acts of generosity. These helped greatly in the judge’s final decision, where Annie Turnbo Malone was given total control of her businesses and settled to pay Aaron Malone $200,000 (approximately $3,000,000 USD in 2019).

Seeking a new start, in 1930, Annie Turnbo Malone purchased an entire city block in Chicago, Illinois and moved her businesses to it. Her wealth made her susceptible to lawsuits, including one settlement in 1937 that forced her to sell her property in St. Louis. Additionally, she was constantly taxed heavily by the Internal Revenue Service who required her to pay a 20 percent tax because it declared her hair and beauty products as “luxuries”. The IRS put a lien on her property and for almost a decade, Turnbo Malone and the federal government were constantly in court for tax issues, including real estate and excise. In 1951, it was awarded control of Poro. The IRS sold most of her property to pay taxes it stated she owed.

Aside from these struggles and trying times, Annie Turnbo Malone remained in business and had thirty-two branches of the Poro College throughout the United States in the mid-1950s. Additionally, she continued to support charitable, civic and educational organizations and institutions throughout the country, especially in her former home city of St. Louis.

On May 10, 1957, Annie Turnbo Malone passed away from complications of a stroke; she was eighty-seven years old.

In her lifetime she received a plethora of awards and honors, including being named an honorary member of Zeta Phi Beta, a Black sorority, and receiving an honorary degree from Howard University.

Sadly, her prominence had diminished and her estate, which was bequeathed to her nieces and nephews, was valued at $100,000 (approximately $1,000,000 USD in 2019).

Some may view this diminishment as sad and the sum as paltry, considering how much wealth Turnbo Malone accrued in her lifetime. However, her influence and impact is priceless. She is becoming more well-known and celebrated in present times. 2019 marked the 109th anniversary of the Annie Malone Parade.

In 1910, the first May Day Parade in St. Louis was held. It has since been renamed the “Annie Malone Parade”. It follows only the Bud Billiken Parade, started by Chicago Defender founder and publisher Robert Sengstacke Abbott in Chicago, as the second largest, African-American parade in the United States. According to the website of the Annie Malone Children and Family Services, the parade “… serves as the agency’s largest major fundraiser and includes an outstanding celebration of fundraising events in May (Community Barbecue, Soiree & Silent Auction, Gospel Concert Explosion, Parade and McDonald’s Blues Fest) for family and friends.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

It is imperative that Annie Turnbo Malone is remembered in contemporary times. Her leadership, compassion and generosity greatly aided African-Americans in attaining a greater quality of life. The mission and work of Annie Turnbo Malone led to increased economic independence and entrepreneurship; greater appreciation for the diverse aspects, including hair and skin, of Black culture; and stronger support of organizations and institutions essential to the advancement of the Black community.