“By the 1960s, Arthur G. Gaston was probably the richest Black man in America. He was the leading employer of Blacks in Alabama and directly and indirectly gave substantial aid and comfort to the Civil Rights Movement … During the 1960s, Gaston was a voice in the wilderness as an apostle of the need for blacks to accumulate ‘Green Power’ by going into business.”

~ David T. Beito, author, historian and professor, University of Alabama

On July 4, 1892, a son was born to Tom and Rosa (née McDonald) Gaston in Demopolis, Marengo County, Alabama; although named “Arthur George”, he would be later known as “A.G.” As a small child, Arthur was reared by his paternal grandparents, Joseph and Idella Gaston. He lived with his formerly-enslaved grandparents due to the death of his father, a railroad worker, not long after his birth, and the relocation of his mother, who worked as a family cook twenty-five miles away in Greensboro. The family for who Rosa worked was of A.B. Loveman, a wealthy Jewish entrepreneur who founded the largest department store in Alabama.

At an early age, A.G. saw the promise of entrepreneurship to improve his life. Although the Gaston elders were poor, they were the only family in the neighborhood who had a swing in their yard. Because of this exclusivity, a young Arthur “charged”, in the form of buttons and pins, the children in the neighborhood for the privilege of playing on the swing.

By the time he was thirteen years old, Arthur and his mother were reunited, as permitted to accompany her when, in 1905, the Loveman family relocated to Birmingham. Upon being settled, Rosa enrolled her son to study at Tuggle Institute, a private educational institution for African-Americans. The institute was founded by Eufaula native, Carrie Tuggle, in 1903. An education and legal reformer, Tuggle centered the mission of her school on the education principles of Booker T. Washington, author, orator and advisor to presidents. He was also the founder and president of the historically Black institution of higher learning, Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama.

The founding organization and primary sponsor of Tuggle Institute was the Order of Calanthe, the women’s auxiliary of the Colored Knights of Pythias, a Black fraternal society. The Colored Knights of Pythias was similar to many Black fraternal organizations in that they were integral in providing mutual aid and promoting social mobilization during and after Reconstruction.

Because of the order’s and, thus, the educational institution’s support to directly and significantly improve the lives of African-Americans, it incorporated Booker T. Washington’s principles centered upon industrial education. Tuggle Institute emphasized skilled labor and independent entrepreneurship and Washington often visited the school.

The presence, accomplishments and speeches of Booker T. Washington inspired many, including A.G. Gaston; in fact, the very first book that Gaston owned was Up from Slavery, the autobiography of Washington. According to authors Carol Jenkins and Elizabeth Gardner Hines in their book, Black Titan, A. G. Gaston and the Making of a Black American Millionaire, “Gaston’s favorite passage stated that ‘[e]very persecuted individual and race should get much consolation out of the great human law, which is universal and eternal, that merit, no matter under what skin found, is in the long run recognized and rewarded…. [T]he Negro … should make himself, through skill, intelligence, and character, of such undeniable value to the community in which he lived that the community could not dispense with his presence.’” It is of significance to note that Jenkins is Gaston’s niece and Gardner Hines is Gaston’s grandniece.

Being greatly motivated by the success of his mother’s employer, A.B. Loveman, and of Booker T. Washington, Gaston sought opportunities to be an entrepreneur. After completing his time at Tuggle Institute, Gaston worked various jobs, including as a bellman at the Battle House Hotel in Mobile and as a subscription salesman for the Birmingham Reporter, a newspaper that was founded and owned by African-American publisher and entrepreneur, Oscar W. Adams, in 1906.

In 1913, A.G. Gaston enlisted in the U.S. Army because of his limited opportunities to become an entrepreneur. Due to segregation, Gaston became a member of the all-Black 92nd Infantry Division. In 1917, during World War I, the infantry was sent to Cherbourg, France for combat. Even though he was stationed in Europe, Gaston was able to send $15 of his $20 monthly pay (approximately $325 of $393 USD in 2019) home to Birmingham, where the funds were used to pay the mortgage on his first real estate investment.

Upon being honorably discharged, Gaston returned to Alabama. He worked as a delivery truck driver for a White-owned dry-cleaning company and as a miner for the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company in Fairfield, a small city outside Birmingham. Always seeking an opportunity for entrepreneurship, Gaston began to sell boxed lunches and snacks of popcorn and peanuts to the miners; the lunches were prepared by his mother, who was a stellar cook. As during his time in the military, Gaston was able to save a great portion of his income in order to further himself and others. He saved approximately two-thirds of his income, and with the additional monies from his lunch business, Gaston began to loan, at twenty-five percent interest, money to his co-workers.

By 1923, two events occurred that would greatly influence the life of A.G. Gaston. He founded his first business, the Booker T. Washington Burial Society, and it was a great success. It was created because as a miner, Gaston often saw miners’ family members, especially widows, soliciting workers and Black churches for monies to bury their loved ones. He organized his society in such a way that members paid twenty-five cents weekly that entitled them to burial services when they passed. His business was greatly impacted by his close relationships with Black ministers in the region and his sponsorship of gospel singers as well as a radio program. The ministers often recommended Gaston’s society to their congregation members and the radio program was the first to be geared for African-Americans in Alabama.

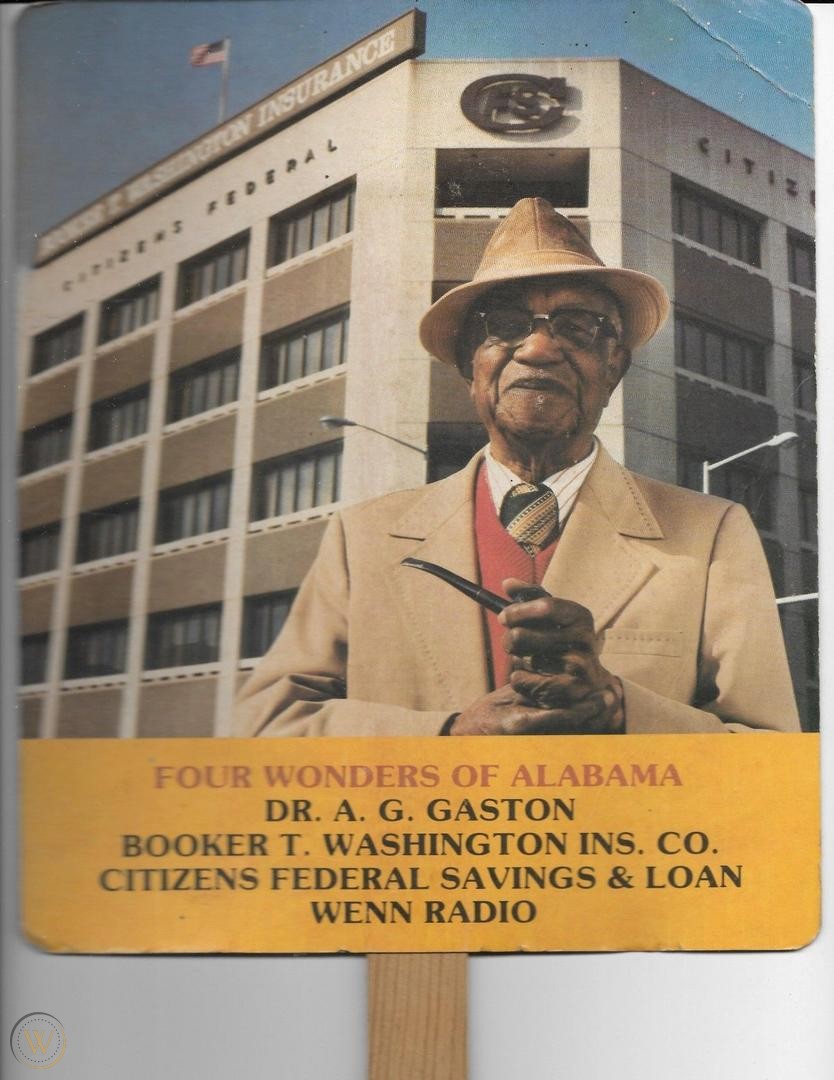

Also, in 1923, A.G. Gaston married Creola Smith. He and her father, A.L. Smith, would create the Smith & Gaston Funeral Home as well as the organization, Smith & Gaston Funeral Directors. The immense prosperity of the Booker T. Washington Burial Society allowed Gaston to further expand, and the burial society was converted to create the Booker T. Washington Insurance Company. Established in 1932, he offered accident, burial health and life insurance. An African-American forerunner of the utilization of vertical integration, A.G. Gaston soon added services, including casket manufacturing, undertaking and sales of burial plots in cemeteries he owned, to supplement the insurance policies he sold. As Jenkins and Gardner Hines wrote in their book, “As Carnegie was to steel, Gaston was to dying.”

Great success continued to be attained by Gaston. He had an uncanny ability to see and fulfill a need within the African-American community. In 1938, A.G. Gaston purchased and renovated a property on the periphery of Kelly Ingram Park in downtown Birmingham. The property would be used as the site for the Smith & Gaston Funeral Home. That same year, sadly, his wife, Creola, passed away.

In 1939, he and his second wife, Minnie, started the Booker T. Washington Business College in order to train people to become skilled typists and business managers, as he often experienced a shortage of them in his own enterprises. In his review of Black Titan, A. G. Gaston and the Making of a Black American Millionaire for The Independent Review: A Journal of Political Economy, historian David T. Beito detailed Gaston’s keen business acumen. In his article, Beito wrote, “Gaston continued to fulfill needs and expand his empire by adding businesses, including the Vulcan Realty and Investment Company, the A. G. Gaston Home for Senior Citizens, the WENN-FM and WAGG-AM radio stations, S & G Public Relations Company, and the A. G. Gaston Motel.”

He founded the Citizens Federal Savings and Loan Association, one of the most prominent Black-owned banks in the United States. Gaston created this financial institution because of the pervasive denials of loans by White-owned banks to Blacks. Gaston’s Citizens Federal Savings and Loan Association was, according to Beito, “… the first Black-owned financial institution in Birmingham since the closing of the Alabama Penny Savings Bank 40 years earlier.”

During this time, A.G. Gaston also started the Brown Belle Bottling Company in order to create, bottle and sell a soda pop called “Joe Louis Punch”. This was the only venture in which he did not receive great success.

In 1954, he opened the A.G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham. Prominent guests included Colin Powell as well as featured entertainers, such as Little Richard and Stevie Wonder, who performed at the motel. Always meeting a need in the Black community, Gaston opened the motel to host Black visitors to Birmingham, as they would be denied stay in White hotels that practiced segregation. Featuring custom-made materials, including draperies, high-end furniture and exceptional customer service, the A.G. Gaston Motel, according to author Carol Jenkins in a video interview on Gaston by the Smithsonian, was “It was really a first-class place … it was considered the finest Black motel in America at the time …” By 1960, according to the biography on him at BlackPast website, A.G. Gaston “…employed the largest number of African Americans in the state and he had become one of the wealthiest African Americans in the United States.”

In Black Titan, A. G. Gaston and the Making of a Black American Millionaire, the authors discuss how Gaston “worked quietly for equal treatment for Blacks” throughout his life. Since the early 1920s, he urged his customers to register to vote and in the 1950s, his private threat of closing his accounts with First National Bank if the “Whites Only” signs were not removed from public water fountains was heeded. In 1956, his hire of Autherine Lucy provided her with the financial support needed to become the first African-American student to register at the University of Alabama. Lucy, who rode in Gaston’s car to register on campus, had filed a lawsuit in 1955 to integrate the university. Additionally, Gaston provided financial assistance to Tuskegee activists forced out of their homes because they challenged voting discrimination.

Gaston was criticized by some, including civil rights leaders Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth as well as activists such as Hosea Williams, for his covert ways of support. Gaston was a member of the Committee of 100, a group of Black and White Birmingham businessmen who were committed to quietly integrating the city.

Ironically, in 1956 when Shuttlesworth founded the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, the organization held its initial meeting at Gaston’s downtown office. Also, it was at Gaston’s motel where King, Jr., Rev. Ralph Abernathy and other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement set up their “war room” in Room 30, devising strategies to implement for their public demonstrations and marches. It should be emphasized that it was A.G. Gaston who paid the $5, 000 (est. $42, 000 USD in 2019) bail for King, Jr. and Abernathy from jail when they were arrested during the Birmingham Campaign in 1963.

His support of King, Jr., Shuttlesworth, Abernathy and others active in the Civil Rights Movement led to Gaston himself becoming a victim of violence when his motel was bombed on May 11, 1963. Four people considered to be associated with the Ku Klux Klan attempted to blow up his motel because it was where King, Jr. and Abernathy were staying. On the same night that the motel was bombed, the home of Reverend A. D. King, Martin’s brother, was also bombed. Later that evening, the two bombings fueled Blacks to riot in a twenty-eight-block section of downtown Birmingham. Birmingham police officers and Alabama state troopers responded to the crisis and subsequently beat rioters and bystanders. More than fifty people were injured as police were dispatched to clear Kelly Ingram Park.

Violence continued to rage in Birmingham, again impacting Gaston. On September 8, 1963, his own home was bombed. Fortunately, no one was injured and the house suffered little damage. The previous day, he and his wife had been guests at a state dinner of President John F. and First Lady Jackie Kennedy at the White House.

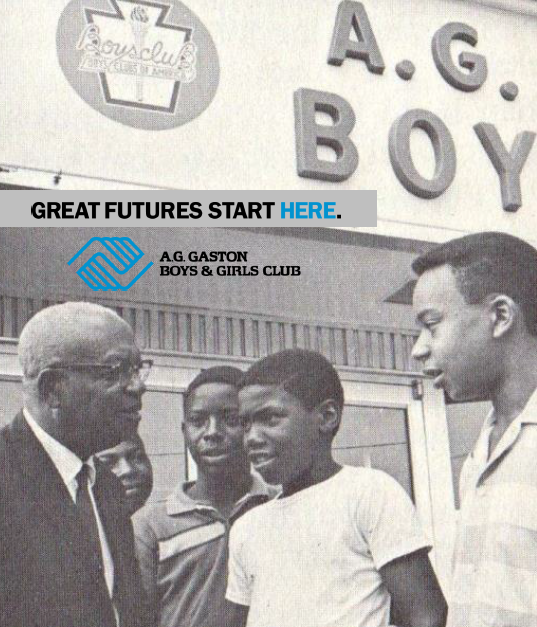

In 1968, Gaston published his autobiography, Green Power: The Successful Way of A. G. Gaston. The primary reason for its publication was to promote Black entrepreneurship within the Black community. His memoir was received well and coincided with the development of the A.G. Gaston Boys Club in Birmingham. He donated $50,000 ($360,000 USD in 2019) to establish the club and served as its president.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In his lifetime, A.G. Gaston was the recipient of numerous honors and awards. In 1975, he received an honorary law degree from Pepperdine University. In 1976, he was named an honorary president of Troy University and also “Citizen of the Year” by the Alabama Broadcasters Association. Tragically, that same year, Gaston was again the victim of violence. He and his wife were kidnapped by an intruder. Beaten with a hammer, handcuffed, and driven around Birmingham for hours. The assailant was ultimately apprehended by city police. It is believed the reason for his kidnapping and its accompanying violence was related to his wealth and not his race.

He also served on the boards of trustees, according to the Herbert J. Lewis biography on A.G. Gaston featured in the Encyclopedia of Alabama, at “Tuskegee University, Daniel Payne College, the Gorgas Scholarship Foundation, and the Eighteenth Street Branch YMCA. In 1992, he was named by the magazine Black Enterprise as ‘Entrepreneur of the Century’ … He also served on the boards of directors for the Jefferson County United Appeal, the Jefferson County Mental Health Association, the National Business League, Operation New Birmingham, and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.”

In 1986, when he was ninety-four years old, Gaston added to his empire by developing the A. G. Gaston Construction Company. According to Lewis’ biography on Gaston in the Encyclopedia of Alabama, the following year, Gaston “… rewarded his long-time employees by creating an employee stock option plan and sold the Booker T. Washington Insurance Company with assets totaling $34 million to his employees for only $3.5 million.” Although he suffered a stroke in 1992, Gaston continued to operate the Citizens Federal Savings Bank and the Smith and Gaston Funeral Home during the early 1990s.

On January 19, 1996, A.G. Gaston passed away from natural causes; he was 103 years old. According to authors Jenkins and Gardner Hines in Black Titan, A. G. Gaston and the Making of a Black American Millionaire, the net worth of A.G. Gaston was greater than $130,000,000 (approximately $213,000,000 USD in 2019)!

He left behind the Booker T. Washington Insurance Company, the A.G. Gaston Construction Company, Smith and Gaston Funeral Home, and a financial institution, CFS Bancshares. The A.G. Gaston Motel is owned by the City of Birmingham. Because of its importance as a gathering place for civil rights leaders and activists and the scene of the bombing in 1963, it has been designated as part of the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument by President Barack H. Obama in January 2017.

(No copyright infringement intended).

“I never went into anything with the idea of making money … I thought of doing something, and it would come up and make money. I never thought of trying to get rich.” ~ A.G. Gaston