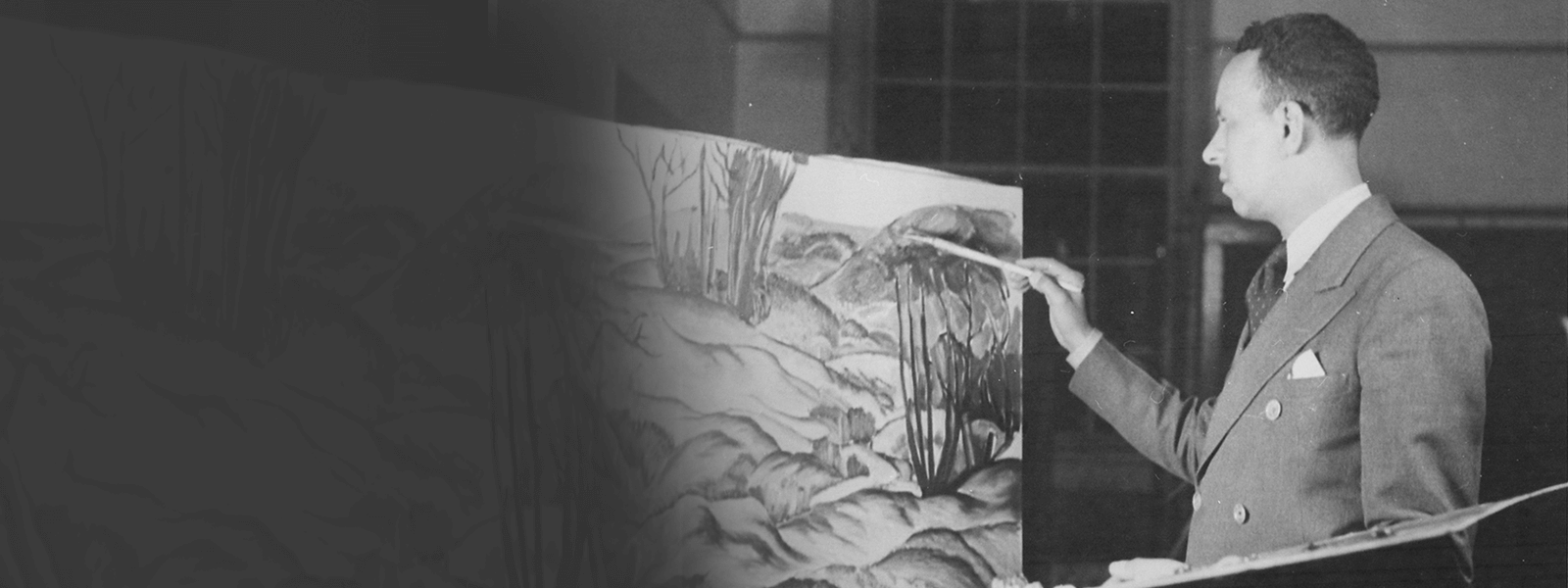

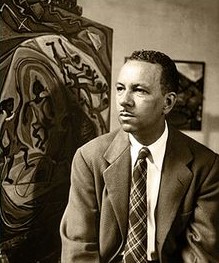

“A first generation artist of the New Negro Movement, Hale Aspacio Woodruff created paintings, prints, and murals that depict the historic struggle and perseverance of African Americans. Though some of his work, such as his Afro Emblems series, is entirely abstract, Woodruff is perhaps best known for his American scenes that combine a representational style with a modern idiom and African aesthetic.”

~ The Johnson Collection

Born on August 26, 1900 in Cairo, Illinois, Hale Aspacio Woodruff was reared in Nashville, Tennessee. When he was a small child, his mother relocated to the South after the death of Hale’s father. As a single parent, she spent many hours away from him in order to support their family. While his mother was working, he spent much of his time drawing. His great interest in art led him to serve as a political cartoonist, first for the paper of Pearl High School where he matriculated. He later worked in this capacity for an African-American newspaper in Indianapolis, to where he moved in 1919.

Hale Woodruff’s move to Indiana’s capitol city led him to study at the John Herron Art Institute. It was at this school where he first learned about African and African-American art, which would greatly impact him for the rest of his life. This inspiration became more pronounced when he met African-American art legend, William Edouard Scott. A leading illustrator, muralist and portraitist, Scott had recently returned from a visit of Europe. A leading advocate for representing Blacks more authentically and celebrating Africa Diaspora culture, Scott had an incredible influence on Woodruff.

In 1926, Woodruff entered an art competition for African-Americans that was sponsored by the prestigious Harmon Foundation. Winning second prize for his painting, The Old Woman, he was awarded $100 (approximately $1500 in 2021). Further developing his personal interest to study art, especially African, abroad, Hale Woodruff bought a one-way ticket to Paris, France. He would remain in “La Ville Lumière”, or the “City of Lights”, for four years.

There, the African-American artist studied at the Académie Moderne and the Académie Scandinave. Hale Woodruff also became a member of what he referenced as “The Negro Colony”, a collective of African-American artists and intellectuals residing in France. These Black expatriates included Josephine Baker, Alain Locke, Augusta Savage and his personal hero, Henry Ossawa Tanner. Tanner, who had permanently settled in Paris in 1891, was the first African-American artist to gain international prominence. His oil painting, Daniel in the Lions’ Den, was admitted into the Salon, the official art exhibition of Paris’ Académie des Beaux-Arts, in 1896.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Woodruff was able to meet and build with Tanner, who was highly encouraging of Woodruff’s work. In the profile on Hale Woodruff from Hale Woodruff, 50 Years of His Art, Exhibition Catalogue (1979) at the Smithsonian American Art Museum website, it reads, “Woodruff spent several years in France and finally met Tanner, whom he described as ‘very hospitable … and very elegant.’”

Also in Paris were great artists of European descent. Similar to their African-American counterparts, they too would be magnificently influenced by Africa Diaspora culture. In “Hale Woodruff (1900-1980) at The Johnson Collection website, the author notes, “Though they did not directly engage with the Parisian artist circle comprised of Gertrude Stein, Picasso, Matisse, and others, Woodruff and his friends were nonetheless aware of their artistic innovations and dealt with similar aesthetic issues in their own work. At the same time, Woodruff explored the ethnographic market with Alain Locke and studied African sculpture in books.” Woodruff began incorporating African motifs and symbolism as well as abstract techniques of Cubism in his own art. According to his biography at Brittanica.com, Hale Woodruff’s “best-known work of that period, The Card Players (1929), shows the stretched human forms and flattened skewed perspective typical of that movement.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

The impact of The Great Depression led Hale Woodruff to return to the United States in 1931, having accepted a position to teach art in Atlanta, Georgia. That same year, he married Theresa Ada Baker and their union was later blessed with one son, Roy.

He likened his return to the Southern United States to that of, again, being “home”. While in Atlanta, he taught at several historically Black institutions of higher learning: Atlanta University and its Laboratory High School; Morehouse College, which was exclusively for men, and Spelman University, which was exclusively for women.

Woodruff taught at Atlanta University from 1931 until 1946. There, Woodruff founded the “Atlanta School”, the first university art department for Black students in the South. It was also known as the “Outhouse School”, as per The Johnson Collection profile because “The latter designation was inspired by Woodruff’s realist approach that demanded the inclusion of all visible forms in his students’ landscape paintings, including less picturesque elements such as privies.” His landscapes touchingly captured life for African-Americans in Georgia. The Smithsonian profile detailed that these works, “are simpler in concept and dominated by diagonal accents and bold contrasts in darks and lights. Whether in oil or watercolor, many of Woodruff’s landscapes of the 1940s depict tarpaper shanties, community wells, and outhouses to the extent that he frequently referred to this group of landscapes as the ‘Outhouse School’. These subjects were handled accurately and sensitively but without sentimentality.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Expanding upon his vision and outreach, the Smithsonian American Art Museum biography of Hale Woodruff proclaims, “It was Woodruff who was responsible for that department’s frequent designation as the École des Beaux Arts” of the Black South in later years. As he excelled as chairman of the art department at Atlanta University, his reputation also grew as one of the most talented African-American artists of the Depression era.”

In 1934, Hale Woodruff traveled to Mexico to learn the fresco techniques of celebrated muralist Diego Rivera. Upon his return, he continued his work at Atlanta University. He also taught and accepted a commission at Talladega College, another historically Black institution of higher learning in Talladega, Alabama.

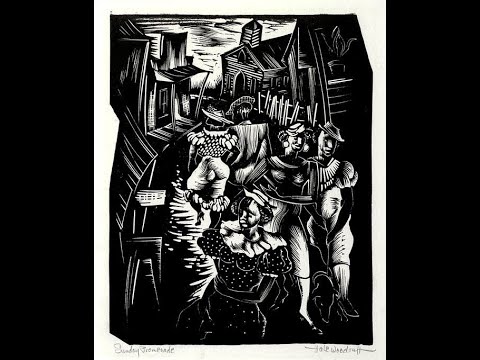

Woodruff’s art styles transitioned from abstract and Cubism, giving way to curvilinear forms. Building upon his traditional modes of oil and watercolors, he also became involved in printmaking. His work, which had become more representational and realistic, depicted scenes of daily life for many Blacks. Powerfully guiding his work were socially-conscious issues, including poverty, racism and, significantly, lynchings, greatly affecting African-Americans, especially in the South. These expansions of style, media and themes would brilliantly impact what became the most popular and critically-acclaimed work of Hale Woodruff’s career: the Amistad murals.

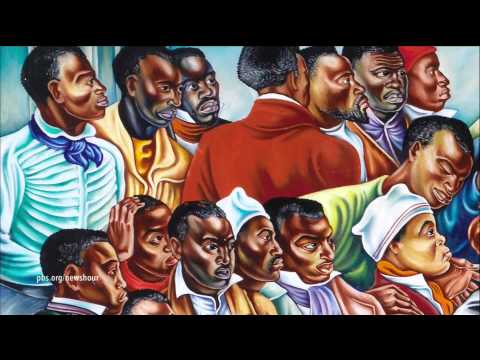

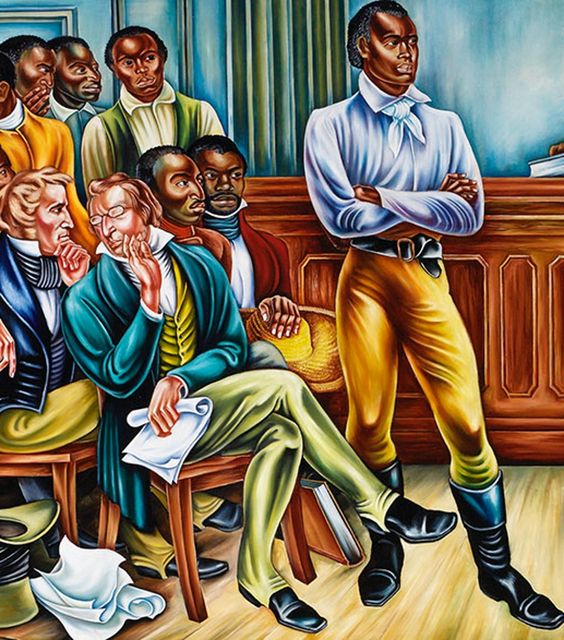

Created from 1939 until 1940, these three murals present key events involved in the 1839 insurrection of members of the Mende aboard the Amistad, a ship belonging to Spain. The three murals are The Mutiny on the Amistad, showing the revolt of the enslaved Mende; The Trial of the Amistad Captives, presenting the revolutionaries, including Cinque, being on trial before the U.S. Supreme Court; and The Repatriation of the Freed Captives, the return of the captured Mende to Sierra Leone. A mitigating factor in them being granted their freedom was the prohibition of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade by the United States.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

Installed at Savery Library at Talladega College, the murals were commissioned to honor the centennial anniversary of the Mende on board the Amistad. A centrally-located image of the ship is embedded in the lobby floor at Savery; walking on this tribute is prohibited. Also housed in the College’s library are three other murals, each dealing with aspects of African-American history. Created in 1942, they are The Underground Railroad, Opening Day at Talladega College and The Building of Savery Library.

These murals remain at Savery Library where efforts to conserve them were undertaken in 2011. According to the page on Hale Woodruff’s art at Talladega at the High Museum of Art website, it champions, “Today the murals remain symbols of the centuries-long struggle for civil rights. This project, a collaboration between the High Museum of Art and Talladega College, conserves these works and presents them to a national audience for the first time.” This conservation was essential to the engagement of contemporary viewers and future generations. Beginning in 2012, Woodruff’s restored murals toured the United States and the Rising Up: Hale Woodruff’s Murals at Talladega College exhibit has been featured at the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama, the Chicago Cultural Center in Illinois, the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. and the New Orleans Museum of Art in Louisiana.

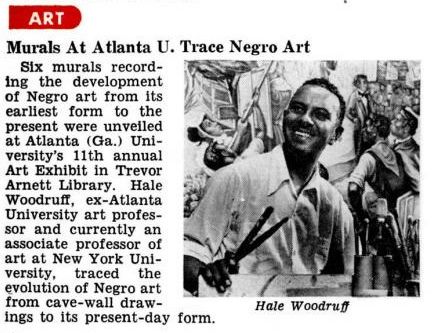

In 1942, Hale Woodruff created the Atlanta University Art Annuals. This yearly competition and exhibit was exclusive to African-American artists. Operating until 1970, it provided an incredible opportunity for Black artists throughout the country to display their work and for guests to engage in African-American art. The Annuals were critical, when one considers the powerful impacts that Africa Diaspora art and artists, such as William Edouard Scott and Henry Ossawa Tanner, had on Woodruff.

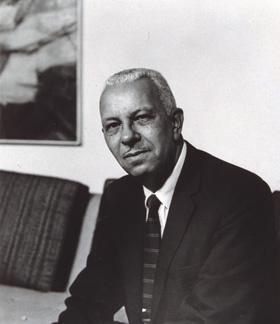

In 1946, Woodruff and his family moved to the East coast, where he taught art at New York University. He remained on its faculty until his retirement in 1968. During this time, he continued to create, including two murals.

He collaborated with African-American artist and friend, Charles Alston, to create The Negro in California History (1949). Also an educator, illustrator, painter and sculptor, Alston was the first African-American supervisor for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. The Negro in California History mural was commissioned by the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company of Los Angeles, California. Founded in 1925 by William Nickerson, Jr., with assistance from George Allen Beavers and Norman Oliver Houston, Golden State Mutual was, at one time, the largest, Black-owned insurance company in the western United States.

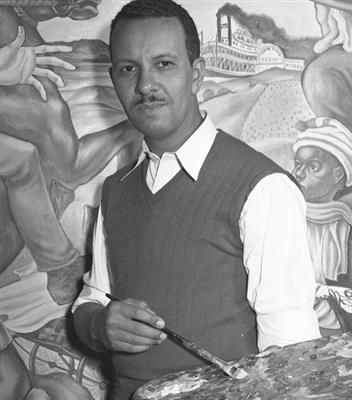

The other mural, Art of the Negro, is comprised of six oil painting panels. These panels are Native Forms, Interchange, Dissipation, Parallels, Influences and Muses. Undertaken in 1950 and 1951, the mural was completed in 1952. It was installed at Clark Atlanta University Art Galleries, where stated on its website page for the Art of the Negro that Woodruff “declared them to be the best of all his murals.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

The mural presents an international, historical account of persons of African descent in the Americas. The Art Galleries provide Hale Woodruff’s insight into this fantastic mural, citing, “It portrays what I call the Art of the Negro. This has to do with a kind of interpretive treatment of African art … I look at the African artist, certainly, as one of my ancestors regardless of how we feel about each other today. I’ve always had a high regard and respect for the African artist and his art. So this mural … is for me, a kind of token of my esteem for African art. One of the motivations again for doing these would be these murals would deal with a subject about which little was known – art and also among Negroes, there was little concern about our ancestry. Then I took the idea that art, being a little known subject, would attract the curiosity and attention of young people, as well as older people, toward further study and in that way the murals would have educational value. I thought also that the unusual subject matter would be timeless in a sense that the arts are always timeless.”

From the 1960s until his death, Hale Woodruff continued to create and collaborate with other African-American artists. His art included his Celestial Gate series, which he began in the early 1950s and extended into the late 1970s. This series witnessed his deft ability to work abstractly, incorporating traditional African iconography. In Swann Galleries’ catalogue, it is regaled that, “One of the artist’s best known series of paintings, Woodruff’s Celestial Gate works incorporate the forms derived from Asante gold weights and the doors of dwellings of Dogon chiefs in Mali with modernist abstraction.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

With fellow artists and friends, including Alston and collage great Romare Bearden, Woodruff co-founded the Spiral Group. This was a collective of African-American artists who created in New York. He also found inspiration in other abstract artist friends, such as Franz Kline and Jackson Pollack.

On September 6, 1980, Hale Woodruff passed away; he was eighty years old.

The artist, whose education included studies at the Chicago Institute of Art and the Harvard Fogg Art Museum, had exhibited solo at the Studio Museum in Harlem (19). He also participated in group exhibitions held in prestigious venues such as New Bertha Schaffer Gallery in New York (1958); the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Howard University Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., New York University and the San Diego Art Museum (all in 1967). His work has also been featured in Two Centuries of Black Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1976) and Hidden Heritage at the Bellevue Art Museum and Art Association of America (1985).

The work of Hale Woodruff may be viewed in collections of esteemed institutions including the Detroit Institute of Arts in Michigan, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

“It’s very important to keep your artistic level at the highest possible range of development and yet make your work convey a telling quality in terms of what we are as people.”

~ Hale Woodruff