“Jim Beckwourth was an African American who played a major role in the early exploration and settlement of the American West. Although there were people of many races and nationalities on the frontier, Beckwourth was the only African American who recorded his life story, and his adventures took him from the everglades of Florida to the Pacific Ocean and from southern Canada to northern Mexico.”

~ The Beckwourth Website

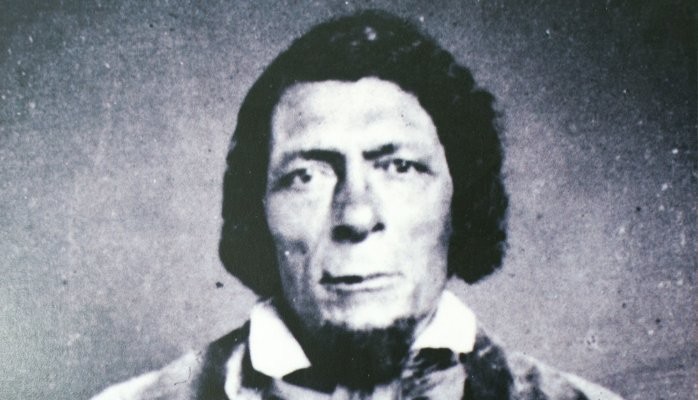

James Pierson Beckwourth was born into slavery in Fredericksburg County, Virginia. His birthdate is not certain for two reasons. Because of his social status of being considered “property”, proper recordkeeping was often not kept. Additionally, Beckwourth would later become known for his folklore, which often included obscured and exaggerated details. However, most contemporary historians agree that his birthdate was April 26, 1798.

James’ mother was a woman of mixed-race heritage. Although she was considered a mulatto, she was enslaved by the Beckwourth family. James’ father was Sir Jennings Beckwourth, a White male, who claimed and reared James. In 1810, he took his son to the Louisiana Territory and afterward to St. Louis, Missouri. There, James lived as a “free” citizen, where he matriculated school and apprenticed for a blacksmith.

James Beckwourth left his apprenticeship, as he and the blacksmith continued to be in conflict and in 1822, he joined an expedition to the mines in the Fever River community. The following year, he worked as a groom on a fur-trading expedition and then resided for a short time in New Orleans. It was during these years, Beckwourth worked on various expeditions sponsored by the American Fur Company and the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. The frontiersman skills he acquired from this work would serve him throughout his life.

(No copyright infringement intended)

Afterward, he returned to live with Sir Jennings until 1824, when he joined General William Henry Ashley on his trapping expedition to the Rocky Mountains. Ashley was a co-founder of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and John Jacob Astor founded the American Fur Company. On this expedition, he worked as a wrangler, handling the horses. In the biography on James Beckwourth at History.com, it’s written, “Beckwourth received a crash course in the dangers of mountain life, just barely managing to avoid death by freezing, starvation, and Indian attacks. Despite the risks, Beckwourth enjoyed being a mountain man, and he spent the next several years as a free trapper.”

At this time, Sir Jennings Beckwourth began appealing to the local court to legally free his son. This is confirmed by The Beckwourth Website, where it’s stated, “His father appeared in open on three separate occasions (in 1824, 1825 and 1826) and ‘acknowledged the execution of a Deed of Emancipation from him to James, a mulatto boy.”

Beckwourth left Ashley’s expedition in 1825 and for the next six years, he lived among the Indigenous Americans, the Crow Nation. He easily and readily adapted aspects of himself to their collective and his life among them including fur trade, warfare, marriage and children. Impressed with his intelligence, charm, bravery, strength and skills, Beckwourth was even named a chieftain and the Crow honored him with their own designation as “Bull’s Robe”.

In 1837, he left the Crow Nation to return to “society”. Various factors, including scarcity of fur pelts, decrease in demand for fur, desire to become wealthy and famous, and wanderlust, influenced his decision to depart from his adopted Indigenous American kin.

James Beckwourth moved to St. Louis, seeking to resume working with the American Fur Company and reconnect with his father. However, he soon learned that St. Louis had drastically modernized and his father, who had returned to Virginia, passed the year prior. Feeling without any anchor, Beckwourth found his way back to the Crow Nation. However, they and many other Indigenous had been infected with smallpox. Though he obviously did not bring the deadly infection with him, Beckwourth’s enemies put out rumors that he purposely carried it. This drastically impacted their reception and perception of the charismatic frontiersman. He left again and joined, as a volunteer, the military of Missouri to serve as a scout.

During this time, he established two trading posts and co-founded the community of Pueblo in Colorado. Five years later, he fought underneath Colonel (future general and United States president) Zachery Taylor in Florida during the Second Seminole War. There are historical accounts that he was a civilian wagon master but Beckwourth himself shared that he worked as a muleteer and courier. In 1840, Beckwourth left the Missouri Volunteers and by 1844, had begun trading on the Old Spanish Trail, located between Arkansas and California, which was owned by Mexico at that time. When the Mexican-American War began in 1846, he returned to the United States, bringing almost 1, 800 horses as spoils of war. Beckwourth’s contributions to the U.S. continued, as he served as a courier for the Army and was instrumental in quelling the Taos Revolt in 1847.

He spent the next decade out West, settling first in Sonoma and Sacramento, California and later in Denver, Colorado. He performed many types of work, such as a professional card player, entrepreneur and civilian scout for various military parties; on one particular excursion, he served as chief scout for General John C. Fremont in 1848.

(No copyright infringement intended).

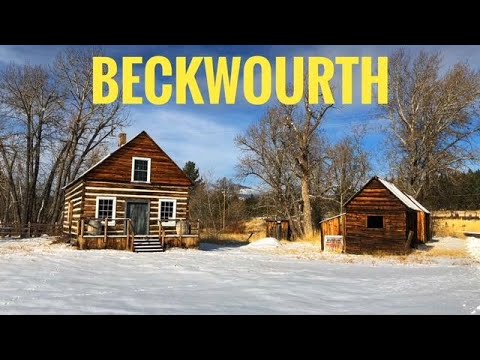

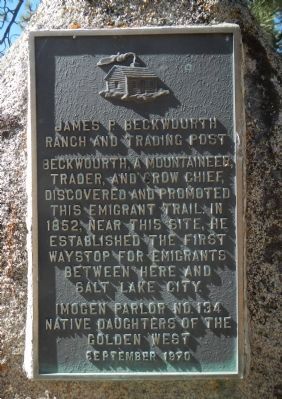

When gold was prominently discovered throughout central California in 1849, a wave of persons from the East coast sought to make their fortune and began moving west. In 1850, James Beckwourth established a low-elevation pass through the Sierra Nevada mountain range; it would be called “Beckwourth Pass”. It was there, in what would become the Sierra Valley, that he built his ranch, hotel and trading post.

The following year, he developed “Beckwourth Trail”. Originally an Indigenous American path through the range, this trail began near Pyramid Lake, included the pass named after him and ended in Marysville. It helped thousands of gold-hunters, settlers and travelers avoid numerous natural dangers and removed approximately one hundred and fifty miles from their journey!

(No copyright infringement intended).

The City of Marysville was to pay Beckwourth but the city suffered several natural disasters, including two fires, of their own and he was told by Marysville leaders that it could not afford to pay him for trailblazing, literally, work.

It was at this time that James Beckwourth met Thomas B. Donner, an itinerant Justice of the Peace and journalist. Highly impressed with the incredible life of Beckwourth, they agreed to collaborate on a biography, of which they would split the profits. Filled with truths and yarns, complete with adventure and most likely, exaggeration, The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, Mountaineer, Scout, Pioneer and Chief of the Crow Nation of Indians, was first published by Harper and Brothers in 1856. Highly popular, a second edition was published in 1858 and a French translation was published in 1860. Sadly, Beckwourth never received any of the profits from this book.

By 1864, Beckwourth temporarily resided in Missouri but settled in Denver. He worked as a storekeeper and a local U.S. agent for Indian Affairs before resuming his work as a scout for the military. It was in this capacity that he was involved in the tragic Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Beckwourth had been hired by Colonel John M. Chivington, head of the Third Colorado Cavalry Regiment. He led a campaign of 675 frontier paramilitary volunteers who had united to annihilate any Arapahos and Cheyenne who had settled in “United States” territory. The brutal unit killed and/or mutilated an estimated 70 to 500 “friendly” Cheyenne men, women and children. Their refuge had been approved by Edward W. Wynkoop, the commander of Fort Lyon and was to be considered as safe. Chivington and his men completely disregarded the American flag that was raised to indicate their intent for peace. The role of Beckwourth in this massacre is unknown but what is for certain is that the Cheyenne banned trade with him

He continued to work as a trapper and scout, even for the Army in Red Cloud’s War in 1866, until he was well into his sixties. It was on one of his scouting expeditions that most historians reference that he became ill and passed. As with his colorful life, there have been conflicting stories of his death, including being poisoned by a vengeful Crow wife; dying on a hunting trip; and passing away of natural causes among the Crow along the Bighorn River in 1866; or being found dead of natural causes near Denver in 1867. Of these, the most prominently agreed upon is that he died from natural causes among the Crow. It’s stated that the body of James Beckwourth was treated to the traditional funerary customs of the Crow at the Crow Indian Settlement Burial Ground in Laramie, Wyoming.

Although married at least four times (two wives were Indigenous Americans, one was Hispanic and one was African-American), he had four children among them.

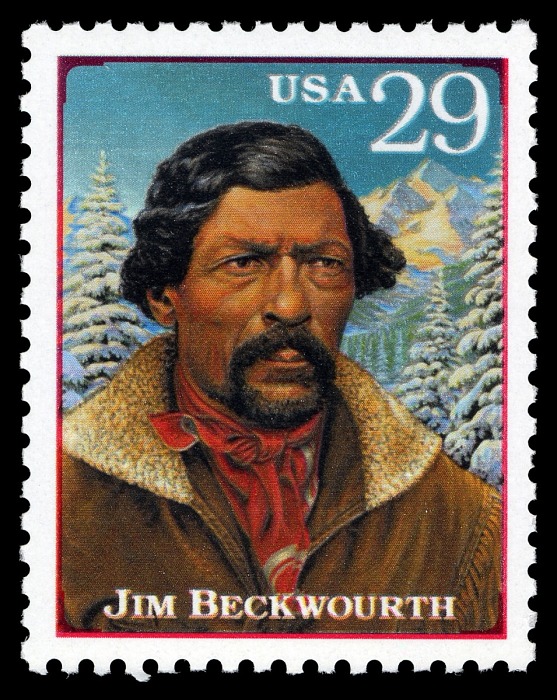

His legacy to the development of the United States is incredible. James Beckwourth is featured in Centennial, the award-winning, bestselling 1974 novel by James A. Michener and its accompanying 1978 twelve-part, television miniseries. For his accomplishments, the U.S. Postal Service placed him on a commemorative stamp in 1994 as one of its honorees in its Legends of the West collection. In 1996, the city of Marysville atoned for its century-plus long neglect of Beckwourth. Honoring their outstanding debt and celebrating his contributions to Marysville, it christened its largest park as Beckwourth Riverfront Park and even developed an event, “Beckwourth Frontier Days”, the only living history festival in northern California.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Thankfully, more and more are learning of the immense achievements of James Beckwourth. Detailing the historical omission and contemporary correction of him, The Beckwourth Website best describes this phenomenal phenomena: “Beckwourth’s role in American history was often dismissed by historians of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many were quite blatant in their prejudices, refusing to give any credence to a ‘mongrel of mixed blood.’ And many of his acquaintances considered the book (The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, Mountaineer, Scout, Pioneer and Chief of the Crow Nation of Indians) something of a joke. But Beckwourth was a man of his times, and for the early fur trappers of the Rockies, the ability to ‘spin a good yarn’ was a skill valued almost as highly as marksmanship or woodsmanship. And while Beckwourth certainly had a tendency to exaggerate numbers or to occasionally make himself the hero of events that happened to other people, later historians have discovered that much of what Beckwourth related in his autobiography actually occurred. Truth is often something much bigger than merely the accuracy of details. And to discover the truth of what life was like for the fur trappers of the 1820s, the Crow Indians of the 1830s, the pioneers of the Southwest in the 1840s, or the gold miners of California in the 1850s, you can find no better source than the life of Jim Beckwourth.”

“Though the Indian could never become a White man, the White man lapsed easily into an Indian.”

~ James Beckwourth