“People didn’t usually fight for land, for trees, and women and children … (but) one person who challenges the rules and refuses to give up can make a difference. Wangarĩ did.”

~ Franck Prévot, author

On April 1, 1940, in Ihithe, a small community in the Nyeri District of Kenya, a baby girl was born into the Muta family; her parents named her Wangarĩ Miriam. Her name, “Wa-ngari” means, “She who belongs to the leopard”. The “ngari”, or leopard, is one of many entities, including the bongo antelope, butterflies and the mugumo trees, that reside in the immense forest near her family’s home. The Muta family, who are of the Kikuyu people, also live near Mount Kenya, a volcano that the Kikuyu consider sacred.

Wangarĩ would be the eldest girl of six children and as such, she was reared to be the second lady of the house. With her mother, she completed tasks, including sewing, cooking, and tending to her younger siblings, traditionally reserved for females. Daughters are to assist their mothers in learning the ways of womanhood because it is strongly promoted that daughters will, one day, be wives and mothers. Wangarĩ Muta began to master these tasks in the home and the field. However, it is in the garden, where Wangarĩ learns to plant, that her mother instills in her the immense value of a tree. This lesson would remain significant to Wangarĩ throughout her life.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Because Kenya was still under tyrannical, colonial control of Britain at that time, her father labored as a farmer. The British imposed their way of living, including forcing of Eurocentric values and Christianity, on the Kikuyu, the most populous nation of people in Kenya. Because of this imposition, Wangarĩ is called “Miriam” during her early childhood. In 1943, the Muta family relocated to Nakuru, where he worked as a chauffeur for the Neylan family, who were White, British colonists. Four years later, the Mutas returned to Ihithe.

Shortly after their return to their home community, her older brother, Nederitu questioned why Wangarĩ did not attend school like him and their brothers. Several days later, their mother enrolled Wangarĩ at Ihithe Primary School to receive an education. This would be the first step on Wangarĩ Muta’s journey in formal learning.

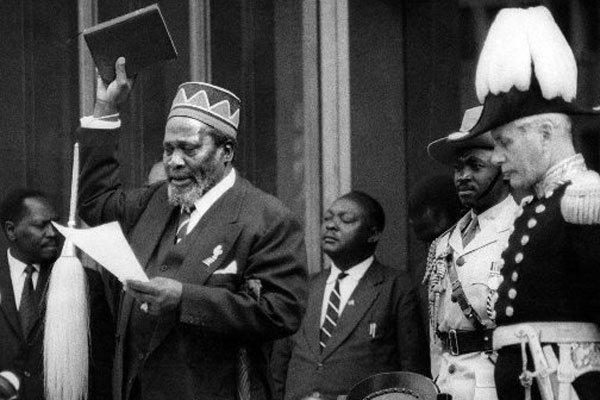

In 1951, Wangarĩ Muta, as a boarding student, matriculated Saint Cecilia’s Intermediate Primary School at the Mathari Catholic Mission in Nyeri. The school, managed by Italian nuns, forbade her native language, Kikuyu, from being spoken and written; only English was considered the acceptable language in which to communicate. While at Saint Cecilia’s, eleven-year old Wangarĩ converted to Catholicism, and chose “Mary Josephine” as her new, Christian name. Because she was away at Saint Cecilia’s, she was protected from the Mau Mau uprising that occurred the following year. Led by Jomo Kenyatta, head of the Kenyan African National Union (KANU), this act was in response to the crushing oppression and deadly violence that the Kenyans suffered under British exploitation. The British retaliated by torturing, imprisoning and murdering thousands of Kenyans. Kenyatta was forced into prison and a state of emergency was declared, where the Muta family had to move into an emergency shelter in Ihithe.

In 1956, Mary Josephine, who had ranked first in her class at Saint Cecilia, was promoted to matriculate the Girls High School of Loreto. Located in Limuru, near Nairobi, the capital, this school was segregated for only Blacks and administered by Irish nuns. This secondary school was the only Catholic high school for girls in Kenya. While Muta was progressing, so was her home country. In 1957, Black Kenyans were granted the franchise, or right to vote, and eight Black Kenyans won legislative seats.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Mary Josephine Muta graduated from the Girls High School of Loreto in 1959. Because the demise of colonialism in East Africa was imminent, Kenyan politicians sought collaboration with other leaders in order to assist in their successful transition to independence. These politicians, including Tom Mboya, one of the founding fathers of the Republic of Kenya, worked with Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts. Kennedy invited six hundred Kenyans to study in the United States. Elected as president in 1960, Kennedy funded this initiative, known as “Airlift Africa” or “The Kennedy Airlift”, through the Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. Foundation. The goal of this union was to make Westernized education available to Kenyan university students with promise; Mary Josephine Muta was selected as one of these students.

In the United States, Mary Josephine Muta entered Mount St. Scholastica College, presently known as Benedictine College, in Atchison, Kansas. While she was studying abroad, Kenya, on December 12, 1963, became an independent country. Jomo Kenyatta, who was considered a hero of the Kenya revolutionary movement, assumed the position of prime minister, then president, of the new nation.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Mary Josephine Muta earned her Bachelor of Science degree, having majored in biology and minored in chemistry and German, in 1964. In 1966, she, funded by the Africa-America Institute, completed a Master of Science degree in biological sciences at the University of Pittsburgh. Muta then returned to Kenya and was to work as a research assistant to a zoology professor who served as the director of the newly-created Veterinary Anatomy Department at the University College of Nairobi. However, upon arrival, she was told that the position for her was no longer available; to which Muta felt she had been discriminated against due to gender and ethnic group discrimination.

Upon her return to her homeland of Kenya, Mary Josephine Muta resumed using her birth name of “Wangarĩ” and met Mwangi Mathai, another Kenyan who had studied in the United States. Seeking employment for several months, she was finally offered by Professor Reinhold Hofmann a position as a research assistant in the microanatomy division in the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University College of Nairobi. Hoffman, who also worked at the Justus Liebig University Giessen in Giessen, Hesse Germany, encouraged Muta to pursue her doctorate.

In 1967, Muta began her doctoral work in Germany, studying at Giessen and the University of Munich. She returned to Nairobi two years later and worked as an assistant lecturer while she was still conducting research for her PhD. That same year, Wangarĩ and Mwangi Mathai married; together, they would, ultimately, have three children: Waweru, Wanjira and Muta. Also, in 1969, opposition parties and a multi-party democracy officially were outlawed in Kenya by President Kenyatta. This ban was due to the assassination of Mboya. As election times neared, Mwangi campaigned, but lost, in his bid for a seat in Parliament.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1971, Wangarĩ Mathai, as she was now known, made history by becoming the first woman in East and Central Africa to earn a doctorate degree. Completing her PhD in veterinary anatomy from the University College of Nairobi (later known as the University of Nairobi), her research was centered upon the development and differentiation of gonads in bovines. She was appointed to become an assistant professor in 1974 and, two years later, was appointed director of the Department of Veterinary Anatomy in 1976. With the former position, she was the first female professor in Kenya; with the latter position, Mathai was also the first woman to chair a university department in the two regions.

From 1976 to 1987, Mathai was highly active in the National Council of Women of Kenya, including serving as its chairperson the last six years of her involvement with the organization. It was during her time with the Council that, in 1977, she developed her own grassroots organization, the Green Belt Movement (GBM). Its platform involved promotion of women’s rights; creation of democracy; release of political prisoners; environmental conservation, including planting of trees; and reduction of poverty.

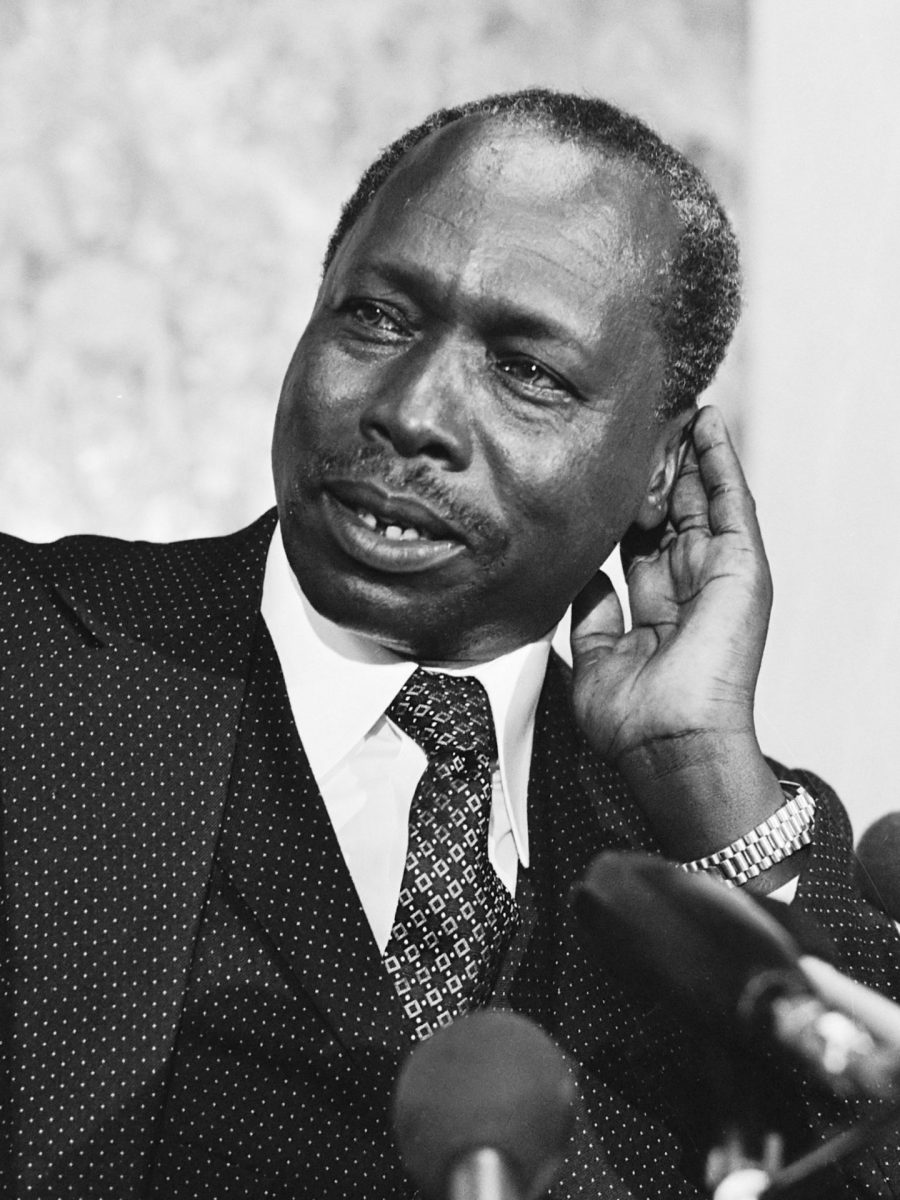

In late 1978, President Jomo Kenyatta suffered cardiac arrest and passed away. His vice-president, Daniel arap Moi, assumed office and was a fierce opponent of Wangarĩ Mathai. With an iron fist, Moi ruled Kenya for twenty-four years. During his tenure, his authoritarian rule greatly diminished progress for many Kenyans of Kikuyu descent, Mathai included. She bravely spoke against the pervasive abuses of Moi, including his violation of civil and human rights and abuse of the country’s environment.

As Wangarĩ battled against Moi, her husband, Mwangi Mathai filed for divorce. Citing that she was too independent and even accusing her of an affair (which was unfounded), the divorce was very ugly and costly; Mwangi even refused to allow Wangarĩ to keep his surname. Instead of changing her name, she added an extra “a” (the Kikuyu spelling) and would be known going forth as “Wangarĩ Muta Maathai.”

Understanding how integral politics is to every aspect of life, Wangarĩ Muta Maathai decided, in 1982, to run for a legislative position within Kenyan government. Although she was unsuccessful in four of her attempts, in 2002, she, as a candidate of the National Rainbow Coalition, was finally elected to serve. The Coalition defeated the dominant party, the Kenyan African National Union, and Maathai won ninety-eight percent of the vote of the Tetu Constituency. In 2003, Maathai was appointed the Assistant Minister in the Ministry for Environment and Natural Resources; she served in this capacity for two years. The same year that she assumed her appointment with the Ministry for Environment and Natural Resources, she founded the Mazingira Green Party of Kenya. This new political party was a member of the Federation of Green Parties of Africa as well as Global Greens. Its purpose involved promotion of candidates who, in supporting the GBM, run for office on the platform of environment conservation.

(No copyright infringement intended).

While many incidents prompted her involvement in politics, two in particular brought her in conflict with President Moi. The first one involved his attempt to construct a 60-story building as well as a statue of himself in Uhuru Park, located in Nairobi; the second centered upon his real estate project in the forest of Karura. Maathai, supported by the Green Belt Movement, was successful in halting both of these attacks. After these incidents, the area in Uhuru Park, in 1989, became known as “Freedom Corner”.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

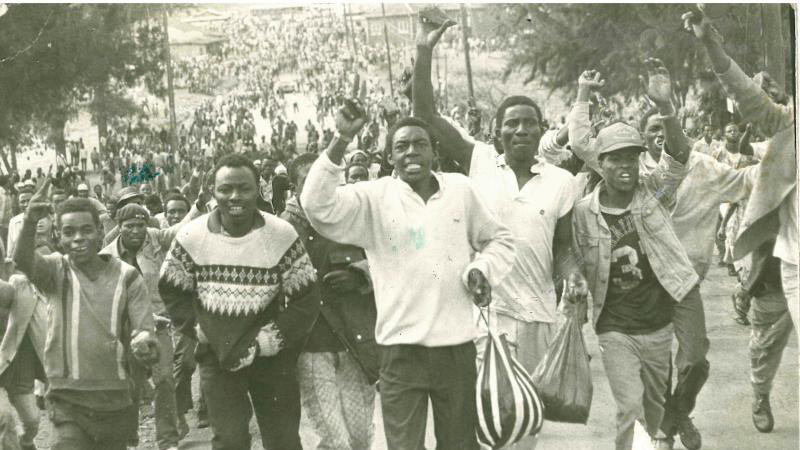

In the following year, on July 7, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators, including Wangarĩ Maathai, gathered in Kamukunji Park to advocate for democracy. Most of the participants, many of who were students, were protesting against deforestation and the corrupt administration who sanctioned it. Tragically, law enforcement officers opened fire in the crowd, murdering several dozen people and maiming hundreds. The police also beat protestors, including Maathai who was severely injured and jailed. This day, known as “Saba Saba” (which is Swahili for “7/7”, the date of the massacre), would play a pivotal role in the re-installment of democracy to Kenya.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

Over the next several years, Maathai, continuing to be viewed and treated as a menace by President Moi and Kenyan government. She was repeatedly jailed, threatened and even received death threats for her activism. In an interview with The Economist, Maathai asserted that “Nobody would have bothered me if all I did was to encourage women to plant trees. But I started seeing the linkages between the problems that we were dealing with and the root causes of environmental degradation. And one of those root causes was misgovernance.”

A significant part of this misgovernance by President Moi was his suspension of Parliament in 1993. It was replaced with a single-party government, the Kenyan African National Union, which gave Daniel arap Moi complete power. Maathai, though in hiding, remained active with GBM and gained international support for her advocacy. With the development of her new political party, the Mazingira Green Party, she worked diligently to unite Kenyans. One of her gestures of unification was the offering of young trees from nurseries to opposing neighboring groups. In Wangarĩ Maathai: The Woman who Planted Millions of Trees, Franck Prévot wrote, “Little by little, those peace trees bear their fruits. Wangarĩ even succeeds in convincing soldiers to help her cultivate friendships among tribes.”

With the rise of the political party, the National Rainbow Coalition, the Kenyan African National Union was defeated in 2002 and Daniel arap Moi was forced from office. With the installment of a new political party came a new constitution that required Moi to retire. Maathai, lovingly referred as “Mama Miti”, which translates as “The Mother of Trees”, took office the following year. In her administrative position, she began her advocacy for the advancement of Kenya.

For her diligence, persistence and activism, Wangarĩ Maathai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004. According to the literature from the Nobel Peace Prize website, she was recognized by the Norwegian Nobel Committee for “her contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace.” Wangarĩ Maathai was the first African woman and first environmentalist to receive the prestigious prize and, in celebration, she planted a Nandi flame tree at her home in Nyeri, near Mount Kenya.

(No copyright infringement intended).

She became recognized throughout the world for her activism in Kenya and even won support from the United Nations for her causes. In her lifetime, Maathai would serve on numerous boards including the Clinton Global Initiative, the Global Crop Diversity Trust, the Congo Basin Forest Fund, the Discovery Channel’s Planet Green, the Chirac Foundation and Prince Albert of Monaco Foundation. In an interview with People, Wangarĩ Maathai affirmed, “Women needed income and they needed resources because theirs were being depleted … so we decided to solve both problems together.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Wangarĩ Maathai traveled across the world, speaking on behalf of the women, children, the environment and political unity in Kenya. Tree nurseries were created across her home country and they were entrusted to local women to manage. The planting of trees provide fuel as well as stall deforestation and desertification. She was incredibly successful with the GBM: in its provision of training, educating and employing approximately 30, 000 women, the organization is responsible for the planting of more than 50 million trees in Kenya.

On September 25, 2011, in Nairobi, Wangarĩ Muta Maathai passed away from ovarian cancer; she was seventy-one years old.

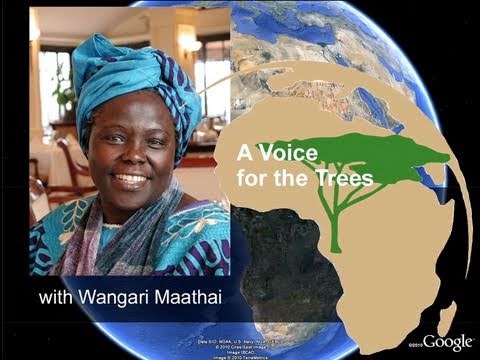

The incredible legacy she left behind includes the countless people she assisted and the Green Belt Movement. They are paramount in carrying on the critical work of Wangarĩ Maathai. With 25% of Earth’s tropical forests located in Africa, it is vital to support the efforts of the GBM, as Kenya continues to lose approximately 125, 000 acres of forest annually. In order to combat climate change and protect biodiversity within the forests of Kenya, in 2006, the United Nations Environmental Programme launched Wangarĩ Maathai’s Billion Tree Campaign. As of 2015, more than 12, 000, 000, 000 trees have been planted in order to greater ensure the survival of the forests. Programs similar to Maathai’s were implemented in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. In 2013, Google, honoring the awesome work of Wangari Maathai, created a Doodle image in celebration of her 73rd birthday.

(No copyright infringement intended).

“I would like to call on young people to commit themselves to activities that contribute toward achieving their long-term dreams. They have the energy and creativity to shape a sustainable future. To the young people, I say, ‘You are a gift to your communities and indeed, the world. You are our hope and our future.’”

~ Wangarĩ Maathai