“Durham can embrace Pauli Murray as an inspiration for our community’s commitment to the struggle for equality, dignity and justice … With this recognition as an Episcopal Saint, even more people will learn about her legacy of activism and the relevance of her ideas to today’s issues.”

~Barbara Lau, director, The Pauli Murray Project

In Baltimore, Maryland, on November 20, 1910, a baby girl was born to William H. and Anne Fitzgerald Murray; they named her Anna Pauline Murray and she was called “Pauli” for short. Her father, a graduate of Howard University, a historically Black university located in Washington, D.C., was an educator in a local high school in Baltimore and her mother worked as a nurse. Both of her parents were of various ethnic heritages but identified themselves racially as “Black”. Sadly, Pauli would lose both of her parents by the time she became a teenager. Her mother passed away, having suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, when Pauli was three years old. Her father, institutionalized at the Hospital for the Negro Insane of Maryland (last known as Crownsville State Hospital) upon suffering effects of typhoid fever, was murdered by a White guard when Pauli was thirteen years old.

As one of six children, Pauli was sent to Durham, North Carolina so she could live with her maternal aunts, Pauline Fitzgerald Dame and Sarah Fitzgerald as well as her grandparents, Robert and Cornelia Fitzgerald. Education was very important to the Fitzgerald family and both of Pauli’s aunts were teachers. In 1926, Pauli, at sixteen years old, graduated with a certificate of distinction from Hillside High School. She then moved to New York City to work and attend an institution of higher learning. While in New York, she stayed with family members, though Black, who were “passing” or identifying themselves as White. Their fair complexion and residency in a White neighborhood conflicted with Pauli, who was noticeably darker, i.e., “Black”. The following year, she moved from living with them after having earned her second, high school diploma, graduating with honors in 1927.

Pauli Murray was inspired by a mentor to enroll at the Ivy League institution, Columbia University in the City of New York. However, Columbia did not allow for women to matriculate at their university. She wanted to apply to attend Barnard College, the women’s college affiliate to Columbia but did not have the resources to study at the partner institution. Murray enrolled at Hunter College, which was a free city university, where she would study for two years until the Wall Street Stock Market Crash of 1929.

Unable to secure stable work to pay for her schooling, she was able to sell issues of Opportunity, the journal published by the National Urban League, a civil rights organization that was headquartered in New York City. However, the conditions led to her health failing and she resigned from that position. Murray then became involved with various programs of the Works Progress Administration, including working at Camp Tera of the She-She-She conservation camp, and taught in the Remedial Reading Project of New York City.

The women’s camp was created by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt as a parallel program to the all-male Civilian Conservation Corp which was developed under the New Deal of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The New Deal, according to history.com, “was a series of programs and projects instituted during the Great Depression by President Franklin D. Roosevelt that aimed to restore prosperity to Americans. When Roosevelt took office in 1933, he acted swiftly to stabilize the economy and provide jobs and relief to those who were suffering. Over the next eight years, the government instituted a series of experimental New Deal projects and programs, such as the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), the WPA (Works Progress Administration), the TVA (Tennessee Valley Authority), the SEC (Securities and Exchange Council)and others, that aimed to restore some measure of dignity and prosperity to many Americans.” At Camp Tera, Pauli Murray met First Lady Roosevelt and their friendship lasted throughout their lives. Murray would later work at the Young Women’s Christian Association.

At Hunter, she was encouraged to write by one of her professors and one of her essays, which centered upon her maternal grandfather, was the inspiration for her later novel, Proud Shoes: The Story of An American Family (1956). This novel was based upon her maternal family, their dealing with racial prejudice and discrimination and life in Durham, North Carolina. As a writer proud of her heritage and socially active, Murray’s articles, poems and even a serialized novel, Angel of the Desert, were sold and published. In 1933, Murray graduated from Hunter College, having earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in English.

During this time that she was working to live beyond survival, she worked diligently on her writing. It was also at this time that Pauli Murray secretly married William Roy Wynn on November 30, 1930; the marriage would be short-lived. The couple only remained together for several months and after an almost twenty-year separation, their marriage was annulled on March 26, 1949.

In 1938, Murray applied to attend the University of North Carolina, an all-White institution, but was barred from admission because she was Black. All public facilities, including schools and institutions of higher learning, in the South were segregated by local ordinances and state laws. Her case, supported by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), was highly publicized in both Black and White newspapers. Murray wrote many officials, including the president of the university and to President Roosevelt, regarding this travesty and often had published the officials’ responses. They were unsuccessful in their fight against the university and it would not be until 1951 that an African-American, Floyd McKissick, would be admitted into the University of North Carolina.

In 1940, Pauli Murray, in her attempts to end segregation on public transportation, refused to remain seated in the back of a Petersburg, Virginia bus and sat in the front area reserved for Whites. On a trip to Durham to visit her aunts, Murray, accompanied by her friend, Adelene McBean, would not sit in the area in which Blacks were forced to sit; the seats in that area were broken. The women were inspired by the civil disobedience teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, who successfully implemented those techniques to overthrow British rule of India. However, the two women were arrested and jailed. The NAACP defended them initially because the organization presumed the charges against Murray and McBean would be related to violation of segregation laws; however, they ceased representation when the charges against the two women were diminished to disorderly conduct.

At this time, the Workers Defense League (WDL), a labor rights organization centered upon socialism, began to represent civil rights violations. The WDL paid Pauli Murray’s fine and she would later be hired as an administrator within the organization. One of the cases in which Murray became highly involved was the case of Odell Waller. Waller, a Black sharecropper in Virginia, was sentenced to be executed for killing Oscar Davis, his White landlord. The WDL defended Waller, stating the Davis had cheated their client and during an intense argument, Waller shot Davis, who had threatened Waller’s life. Murray toured the United States, raising funds for his appeal and advocating to those in power, including First Lady Roosevelt, to assist in ensuring that Waller be given a fair trial. First Lady Roosevelt, on behalf of Murray and Waller, wrote to James Hubert Price, the governor of Virginia, and even convinced her husband, President Roosevelt, to privately request of Price to commute the death sentence assigned to Waller. The governor did not commute the sentence and Odell Waller was put to death on July 2, 1942.

Because of her experience of being on trial for disorderly conduct and advocating for Odell Waller, Pauli Murray decided to enroll in law school to begin a career of practicing civil rights law. She was accepted into Howard University School of Law (HUSL) in 1941 and was the only woman in her law school class. Her gender was always pointed out and, she became acutely aware of the sexism at the university and in her career field. Spinning on the practice of “Jim Crow”, a system of local and state laws that oppressed Blacks based upon racial discrimination, she referenced the duality of racism and sexism that she and other Black women experienced as “Jane Crow”.

While in law school, Murray joined with James Farmer, George Houser and Bayard Rustin to form the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1942. CORE members, inspired by Gandhi and Henry David Thoreau, believed in pacifism and civil disobedience in order to gain equity as humans in society. Her writings, such as “Negro Youth’s Dilemma”, which challenged racial segregation in the US military during World War II; “Negroes are Fed Up”; and “Dark Testament”, a poem on race relations for which she is most famous, were published. She continued being active in challenging “separate but equal” policy in public accommodations and even led sit-ins, a technique greatly utilized during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

In 1942, Pauli Murray was elected to the highest student position at HUSL, chief justice of the Howard Court of Peers, and would graduate first in her class in 1944. The first in the class were historically awarded the prestigious Julius Rosenwald Fellowship for graduate work and Murray wanted to enroll at Harvard University to continue her law studies. She was awarded the fellowship but Harvard Law School denied her admittance because she was a woman. A letter of support from President Roosevelt did not convince the law school to rescind their refusal to allow her to attend. Murray completed her post-graduate work at Boalt School of Law at the University of California, Berkeley. Her thesis, The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment, is considered to be the foundation for modern civil rights law.

In 1945, Pauli Murray passed the bar exam of California and was hired as the first Black deputy attorney general; her service began the following year. Also, that year, she was named “Woman of the Year” by the National Council of Negro Women and she was named “Woman of the Year” by Mademoiselle in 1947. Three years later, Murray published States’ Laws on Race and Color, which investigated and critiqued the unconstitutionality of state segregation laws. Although she was belittled by her professors at HUSL, Murray incorporated psychological and sociological evidence, to accompany legal evidence, in order to directly challenge state segregation laws. She felt that her direct and combined-strategies approach would be more successful in effecting change for African-Americans, as opposed to the traditional approach of confronting “separate but equal” policies. Her approach, significantly the research of psychologists Drs. Kenneth and Mamie Clark, would be influential in the NAACP’s arguments in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). The U.S. Supreme Court would rule that segregated public accommodations were unconstitutional.

By the early 1950s, the civil rights activism of Pauli Murray, like many other African-Americans, prompted her to be a victim of McCarthyism. McCarthyism, as defined by writer Paul J. Achter for Encyclopedia Britannica, was “a period of time in American history that saw Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy produce a series of investigations and hearings during the 1950s in an effort to expose supposed communist infiltration of various areas of the U.S. government.” She was fired from her position at Cornell University because her references, Thurgood Marshall, lead counsel of the NAACP; A. Phillip Randolph, president of The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first, largest and most powerful African-American labor union in the United States; and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt were too radical.

In 1960, Murray traveled to Ghana to explore her heritage and served one year on the faculty of the Ghana School of Law. Upon her return to America, President John F. Kennedy appointed her to his Committee on Civil and Political Rights. Murray was highly active in the Civil Rights Movement; she was also highly critical of the sexism involved in it, even calling out its male leaders and their exclusion of the countless Black women who continued to support the movement, even when the men abandoned the cause. In her essay, “The Negro Woman and the Quest for Equality”, Murray questioned the men leading the various civil rights organizations. She criticized Randolph, the “Architect of the March on Washington”, as no women were invited to be a main speaker or be a delegate member who met with administration at The White House. She spoke and wrote of the dual discrimination of “Jane Crow” suffering by and the blatant disparity shown to Black women, including in their mobilization at the grass-roots level, but near exclusion from policymaking on the national level. Murray also resoundingly praised and lauded the “indomitable determination” of the Black women in the myriad of “Negro causes”.

Always cognizant of her work in civil rights laws and gender equality, she entered Yale School of Law. In 1965, Pauli Murray earned her Doctorate in Juridical Science, making her the first African-American to earn a law degree from Yale. In 1966, Murray co-founded, with Betty Friedan, Kathryn F. Clarenbach, Shirley Chisholm and forty-five other women, the National Organization for Women (NOW). Murray hoped that the activism and success of the NAACP for African-Americans would be replicated by NOW for women. That same year, Murray and Dorothy Kenyon successfully argued White v. Crook, in which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled that women have an equal right to serve on juries. In her brief for Reed v. Reed (1971), a supreme court case that, for the first time, extended the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause to women, attorney and future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg added Murray and Kenyon as coauthors in recognition of her debt to their work.

In 1967, Murray served as the vice-president of Benedict College, a historically Black, liberal arts college in Columbia, South Carolina. The following year, she left Benedict to teach as a tenured professor at Brandeis University. There, she taught American studies and introduced courses in African-American studies and women’s studies, another set of firsts for Pauli Murray.

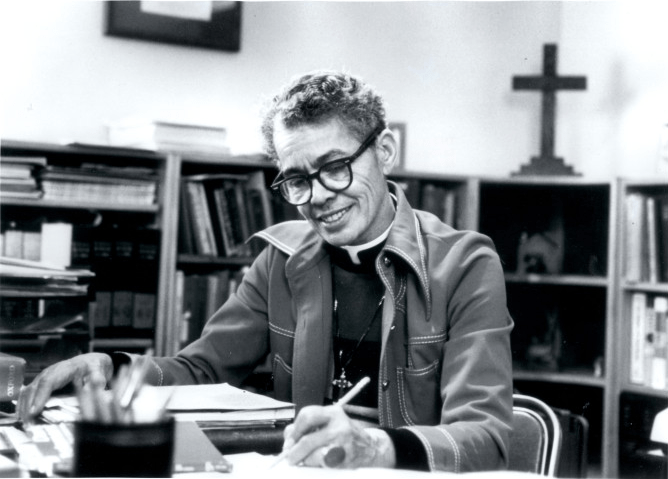

Her groundbreaking work continued throughout her life. Impassioned by her personal and spiritual relationship, she, at the age of sixty-two years old, decided to enter the seminary in 1972. In 1977, Pauli Murray became the first African-American woman to become an Episcopal priest. That year, she led the celebration of her first Eucharist, preaching her first sermon at Chapel of the Cross parish in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. This was the first time a woman performed this act at an Episcopal church in North Carolina. She continued her work as a priest and in 1978, she preached at St. Phillip’s Episcopal Church, the church her grandparents and mother attended in Durham, North Carolina. With a mission geared towards reconciliation, Murray relocated to Washington D.C. and her ministry work centered upon the ill. She worked on this parish assignment for seven years.

On July 1, 1985, Pauli Murray passed away from pancreatic cancer in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She inspired many including Marian Wright Edelman, founder and president emerita of The Children’s Defense Fund; Eleanor Holmes Norton, Chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives; and Ruth Bader Ginsberg, second female U.S. Supreme Court justice. She is remembered for her many contributions and accomplishments, including the Episcopal Church honoring her with sainthood as one of its Holy Women, Holy Men, an honor bestowed upon those whose lives modeled the teachings of Jesus and who made a positive impact in the world. In 2015, the childhood home of Pauli Murray in Durham, North Carolina was designated as a “National Treasure” by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. In 2016, the home was also named a “National Historic Landmark” by the U.S. Department of Interior.

“Pauli Murray College” is one of two residential colleges at Yale University that has been named in her honor; the other is named after inventor, author, statesman, ambassador and postmaster, Benjamin Franklin. Their construction was completed in 2017. In 2018, Murray was selected as an honoree for Women’s History Month by the National Women’s History Project and elected to sainthood by the Episcopal Church on its calendar of saints.

Her autobiography, Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage was published two years after her passing. Its title was changed and released later that year as Pauli Murray: The Autobiography of a Black Activist, Feminist, Lawyer, Priest and Poet.

“If anyone should ask a Negro woman in America what has been her greatest achievement, her honest answer would be, ‘I survived!’”

~ Pauli Murray