“When he attacked the ‘separate but equal’ theory, his real thought behind it was that ‘All right, if you want it separate but equal, I will make it so expensive for it to be separate, that you will have to abandon your separateness.’ And so that was the reason he started demanding equalization of salaries for teachers, equal facilities in the schools and all of that.”

~ Juanita Kidd Stout, attorney & Justice, Supreme Court of Pennsylvania

On September 3, 1895, Charles Hamilton Houston was born in Washington, D.C., to William Le Pré Houston and Mary Houston (née Hamilton). William, whose parents had been enslaved, had become an attorney and Mary worked as a seamstress. His parents’ careers and outreach allowed them to live in the middle and upper-class community, “Strivers’ Section”, of DuPont Circle in northwest D.C. The name of this community, according to the National Park Service website, “derives from the area’s longstanding association with leading individuals and institutions in Washington’s African American community. The recognition of a special enclave of African American leaders in the area goes back more than eighty years, when it was described by a contemporary writer as the ‘Strivers’ Section’ or the ‘community of Negro aristocracy.’”

(No copyright infringement intended).

At fifteen years old, Houston graduated from the all-Black, Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. After, he would then matriculate Amherst College, a private liberal arts institution in Amherst, Massachusetts. Houston, the only Black student in his class, graduated, Phi Beta Kappa, as one of six valedictorians in 1915.

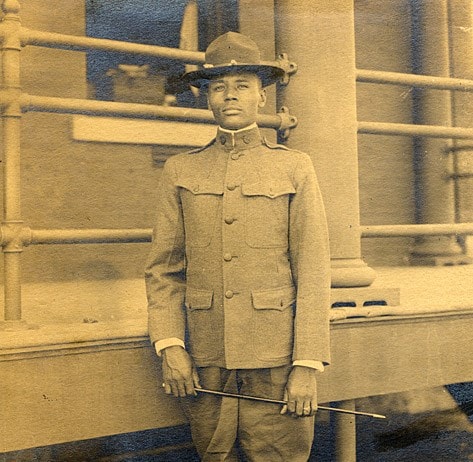

In 1915, Charles Houston returned to Washington, D.C., where he taught English for two years at Howard University, a private, historically Black university that was established in 1867. In 1917, Houston enlisted in the U.S. Army, ultimately becoming commissioned as a First Lieutenant in field artillery. Based at Fort Meade, Maryland, he served in France and Germany during World War I. The racism, discrimination and segregation that Houston experienced while serving in the military cemented his decision to become an advocate, via the law, of those whose rights were infringed upon and/or violated.

(No copyright infringement intended).

After being honorably discharged in 1917, Houston enrolled at Harvard Law School in autumn of 1919. An exceptional learner, Charles Hamilton Houston was the first African-American to be the editor of the Harvard Law Review and earned his Bachelor of Laws degree in 1922 and his Doctorate in Juridical Science degree in 1923. After his graduation from Harvard, Houston was awarded a Sheldon Traveling Fellowship and moved to Spain where he studied civil law at the University of Madrid. In 1924, Houston, having passed the bar exam for the District of Columbia, was admitted to the bar and he began to practice law with his father in Washington. In joining with his father, who would practice law in D.C. for forty years, Charles Houston worked with him until 1950. Because of racial discrimination and segregation, Black lawyers were refused admission to the American Bar Association. In 1925, the National Bar Association was founded by Black lawyers, Joe Brown, Charles P. Howard, Sr., James B. Morris, Gertrude Rush and George H. Woodson. Charles Houston was a founding member of the D.C. chapter, the Washington Bar Association.

Also, in 1924, Charles Houston began to teach part-time at the School of Law at Howard University. He had been recruited by Mordecai Johnson, the first African-American president of Howard University. At that time, Howard University School of Law (HUSL) was open only part-time for night classes. At the time, HUSL, according to Genna Rae McNeil in Groundwork, “had trained approximately three-fourths of the approximately nine-hundred and fifty African-American lawyers practicing in the United States.” By 1929, the trustees of Howard University, spurred by Houston, developed HUSL into a full-time institution and placed Houston as the Resident Vice-Dean.

For the next six years, Howard University School of Law, under the helm of Houston as the Vice-Dean, became the premier institution of law for many Black students. Not only was HUSL responsible for a majority of African-Americans becoming active in the field of law but the institution trained almost one-fourth of the Black students studying law in the United States. It is under the leadership of Charles Hamilton Houston that HUSL earned its accreditation from the Association of American Law Schools and the American Bar Association. With his guidance, a university collaboration between Howard University School of Law and Harvard University School of Law, his alma mater, was created.

Charles Houston also brought in prominent persons active in the field of law, from attorneys to magistrates and judges, to speak and connect with the law students at Howard. He created a network of support that allowed his students to access opportunities that prior to had been unavailable or denied. He mentored students, several who would become successful attorneys and justices, including William Hastie, A. Leon Higginbotham, Oliver Hill, James A. Nabrit, Spottiswood Robinson and Thurgood Marshall. Marshall, who successfully argued Oliver Brown, et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al (1954), known commonly as Brown vs. the Topeka Board of Education, became the first African-American justice to serve on the United States Supreme Court.

In 1935, Charles Hamilton Houston left Howard University to act as the first special counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He often recruited law students, including Marshall, to work with the NAACP. Acting as the first special counsel to this organization for the following five years, Houston developed strategies of litigation which centered upon racially-discriminate housing covenants, inequality before the law and segregated public schools. Houston was so active in his work with the organization that almost every NAACP civil rights case that was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court involved Houston. These cases included successfully suing for the right of African-Americans to be able to serve on a jury,

In 1917, the NAACP was victorious in Buchanan v. Warley (1917) when the United States Supreme Court ruled against local and state jurisdictions’ establishment of restrictive housing based upon race. To get around this ruling, real estate developers and agents created their own restrictive covenants and deeds. In 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Corrigan v. Buckley that these restrictions were beyond the protections of the U.S. Constitution, as these restrictions were acts of individuals.

Under the direction of Charles Hamilton Houston, the campaign against restrictive housing covenants continued. Houston, utilizing modern psychological and sociological data, illustrated that these discriminatory covenants led to dangerous and community-crippling conditions, including poor health and increased crime, for African-Americans. His battle against restrictive covenants never ceased and after twenty-two years, Houston, accompanied by attorneys he trained, was able to have overturned their constitutionality. In Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), the U.S. Supreme Court, citing the Fourteenth Amendment, ruled in favor of the NAACP’s clients. Houston’s use of contemporary data and statistics would inspire him to utilize these resources in later cases, most significantly, Brown vs. Board of Education.

In 1933, Charles Houston successfully saved George Crawford, an African-American accused of murder, from being put to death by the electric chair in Loudoun County, Virginia. Two years later, Houston, accompanied by his team of Black attorneys, argued Hollins v. State of Oklahoma (1935) before the U.S. Supreme Court. They were appealing another case of an African-American man accused of murder. Previously, Jess Hollins, the defendant, had been convicted by an all-White jury and sentenced to death. Houston’s defense team challenged the jury and the conviction was upheld. The U.S. Supreme Court, hearing the case a certiorari (an order when a higher court reviews the decision of a lower court), reversed the lower court’s decision. A new trial was held and Hollins was tried for a third time, again, by an all-White jury. He was found guilty, convicted and, in 1936, sentenced to life in prison. Although it is presently believed that Jess Hollins was innocent, he remained incarcerated and died in 1950.

Southern and western states, including Virginia and Oklahoma, historically excluded Blacks from being able to serve on juries. A significant factor for their exclusion of Blacks was because Blacks were not registered on voter rolls, having been illegally disenfranchised, post-Reconstruction, by local and state barriers to voter registration. Tragically, the challenges for African-Americans to be able to actively participate in this facet of the judicial process have continued into present times.

Regarding public education, Houston attacked segregation by pointedly showing that the “separate but equal” doctrine that stemmed from Plessy v. Ferguson (1897) was immensely unequal. In his travels in the South, he even documented, via a movie camera, the massive inequities of “separate but equal” for African-Americans, from worn and damaged materials to inefficient facilities and severely low salaries for school employees. In his biography featured on the website of the NAACP, Houston’s strategy to combat this inequity was that “his target was broad, but the evidence was numerous. Southern states collectively spent less than half of what was allotted for White students on education for Blacks; there were even greater disparities in individual school districts. Black schools were equipped with castoff supplies from White ones and built with inferior materials. Black facilities appeared to be part of a crude segregationist satire – a design to make Black education a contradiction in terms.

Houston designed a strategy of attacking segregation in law schools – forcing states to either create costly parallel law schools or integrate the existing ones. The strategy had hidden benefits: since law students were predominantly male, Houston sought to neutralize the age-old argument that allowing Blacks to attend White institutions would lead to miscegenation, or “race-mixing”. He also reasoned that judges deciding the cases might be more sympathetic to plaintiffs who were pursuing careers in law. Finally, by challenging segregation in graduate schools, the NAACP lawyers would bypass the inflammatory issue of miscegenation among young children.”

The scope of Charles Houston continued to expand. In 1936, the Supreme Court of Maryland ruled in favor of Houston and Marshall that the University of Maryland could not exclude African Americans based upon race (Pearson v. Murray). In 1939, however, this ruling would be applied to the entire United States in State ex rel. Gaines v. Canada. The U.S. Supreme Court supported Houston’s argument that it was unconstitutional for Missouri to exclude Blacks from the state university’s law school since there was no comparable educational institution of law, under “separate but equal” definition, for African-Americans to attend. The ruling from this federal case would set a precedent that would be extended to cover public elementary and secondary education.

Charles Hamilton Houston created and spearheaded the legal strategy behind Brown v Board of Education (1954) that led to the demise of legalized racial segregation within the United States. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision rendered racial segregation in public primary and secondary school as unconstitutional, thus, “separate but equal” became illegal. This decision came four years after Houston passed.

Houston and Wendell P. Gardner, Sr. founded their own law firm, Houston & Gardner and partners in the firm included Hastie as well as William B. Bryant, Emmet G. Sullivan and Joseph C. Waddy; each of them would be appointed for federal judgeships.

In 1950, Charles Hamilton Houston passed away from a heart attack; he was only fifty-four years old. Although he had been married to Gladys Moran in 1924, they divorced in 1937. He would marry Henrietta Williams, with whom they, in 1941, had Houston’s only child, Charles Hamilton Houston, Jr.

Houston, a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, (the first intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternity established for African Americans), was posthumously awarded the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal in 1950. In 1958, the primary building of the Howard University School of Law was dedicated to Houston and named “Charles Hamilton Houston Hall”. The Charles Houston Bar Association; the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School (which opened in the fall of 2005); and a professorship at Harvard Law School are all in tribute to Houston. He will always be remembered as “The Man who Killed Jim Crow.”

“The hate and scorn showered on us Negro officers by our fellow Americans convinced me that there was no sense in my dying for a world ruled by them. I made up my mind that if I got through this war, I would study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back.”

~ Charles Hamilton Houston