“She gave out faith and hope as if they were pills and she some sort of doctor.”

~ Louis Martin, columnist

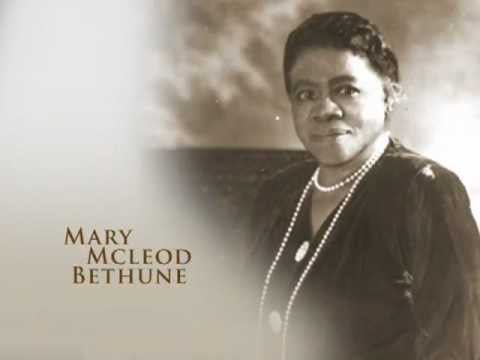

On July 10, 1875, Mary Jane McLeod was born in Maysville, South Carolina to Samuel and Patsy McIntosh McLeod. Her parents, having been enslaved, toiled in the cottonfields. When the Civil War ended, her mother continued to work for the man who previously owned her until she was able to purchase the land on which their family labored.

As the fifteenth of seventeen children born to the McLeods, Mary (and only her two younger siblings) was born free. At the age of five, she began to work in the fields alongside her family and by the age of nine years old, could pick two-hundred and fifty pounds of cotton per day.

When she turned ten, she began her formal education at Trinity Presbyterian Mission School, which was created for African-Americans. The only child of all the McLeod children to attend school, Mary walked miles, each way, every day and shared what she learned with her loved ones. Later in her life, McLeod, in emphasizing the importance of education, would regale that the opportunity for her to learn to read opened the whole world, and its possibilities, to her.

In 1886, Mary McLeod graduated and was awarded a scholarship to matriculate at Scotia Seminary for Girls (presently known as Barber-Scotia College) in Concord, North Carolina. Upon her graduation from the seminary, she moved to Chicago to attend the Dwight Moody’s Institute for Home and Foreign Missions (also known as Moody Bible Institute). Her goal was to become a missionary but after completing her studies, she found no missionary openings, as no church would sponsor her.

(No copyright infringement intended).

She returned to the South and began to teach in schools in Illinois, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. While educating Blacks in South Carolina, McLeod found her divine calling, having realized that the gifts she had as a Christian and an educator were needed just as much by those Blacks in America as those in Africa. The dream of opening her own school took Mary McLeod Bethune to Florida.

During her time in teaching at the Kendall Institute in Sumpter, South Carolina, she met fellow teacher, Albertus Bethune. In 1898, at the age of twenty-three years old, Mary and Albert would marry; their only child, Albert McLeod Bethune, was born in 1899.

The Bethunes moved to Palatka, Florida, where Mary worked at the Presbyterian Church and also sold insurance. Their marriage would only last several years, ending in 1907. Mary was determined to support herself and her son, as Albertus had abandoned their family. Believing that education was integral to advancement for Blacks, she opened a high school, hospital, and, notably, in 1904, the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute for Negro Girls in Daytona, Florida. It opened with five students, quickly growing to a population of more than two-hundred and fifty students attending each year.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Bethune was one of many African-Americans who purposely moved to this area of Florida, because the recent construction of the Florida East Coast Railway sparked a population boom of African-Americans. The institute became popular among the African-Americans who settled around it. Its prominence prompted the merging of it with the Cookman Institute for Men in Jacksonville in 1923; from 1929 on, the merged institutes became known as Bethune-Cookman College.

As one of the earliest institutions that allowed African-Americans to earn a degree, Bethune served as the college’s first president from 1923 to 1942 and again from 1946 to 1947. At the time, Bethune was one of the few female administrators leading an institution of higher learning. With scant resources to develop her school, she, according to the biography stub at Encyclopedia Britannica, “ … worked tirelessly to build a schoolhouse, solicit help and contributions, and enlist the goodwill of both the African American and White communities.” Under her leadershop, the college was awarded full accreditation and grew its enrollment to more than 1,000. students per year.

As she worked, leading the college, Mary McLeod Bethune further developed her passion for education and quest for improved conditions for Blacks, especially women. Her passion and quest led her to become an activist for and national leader of African-Americans, women and the youth. Having served as the president of the Florida chapter of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACW), in 1924, Bethune defeated investigative journalist and educator, Ida B. Wells, when Bethune was elected to be the association’s national president. As the president, Bethune attempted to guide the association beyond the traditional rhetoric and, according to the biography written by Herbert G. Ruffin II in BLACKPAST, “of self-help and moral uplift toward the politics of agitation for integration by attacking racial discrimination and segregation in the Federal government.”

Because of the difficulty of eliminating Jim Crow in the federal government and the internal politics of the NACW, Bethune, in 1935, founded the National Council of Negro Women, of which she served as its national president. This organization was created in order that the many African-American women interest organizations involved could collaborate. The collaboration was needed, Bethune felt, in order to successfully manage the many critical issues African-American women experienced. Bethune acted as president until 1949.

Bethune’s activism, including leading voter registration drives and battling against school segregation and inadequate healthcare for Black children, brought her to government service. Her leadership prompted her in actively transitioning Black voters away from the Republican Party, who many African-Americans had supported because of the contributions they felt President Abraham Lincoln, a Republican, made in support of Blacks. Bethune was appointed as an advisor and a delegate to several national commissions on child welfare, education and housing including the Child Welfare Conference, under President Calvin Coolidge, and the National Commission on Child Welfare and the Commission on Home Building and Home Ownership, under President Herbert Hoover. She was appointed to lead a delegation to Liberia for observance of President William V.S. Tubman and served on the Committee of Twelve for National Defense under President Harry S. Truman.

(No copyright infringement intended).

However, her most significant contributions in public service occurred during the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Considered to be dear friends and a trusted advisor with the president and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Bethune was appointed as a special advisor on minority affairs. In this capacity, she organized two national conferences, “Problems of the Negro” and “Negro Youth”, centered upon the myriad of difficulties African-Americans suffered. In 1936, President Roosevelt selected her as director of the Division of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration. One of the primary responsibilities of this position was to assist young adults in securing stable employment. As director, Bethune, as Ruffin II wrote, “led an organization that trained tens of thousands of Black youth for skilled positions that eventually became available in defense plants during World War II. She made sure Black colleges participated in the Civilian Pilot Training Program, which graduated some of the nation’s first Black pilots. This presidential appointment made Bethune the highest ranking African-American women in the United States government. She remained active in this position until 1944.

Vigilant in her fight against racial discrimination and its accompanying effects, including lynching, voter discrimination and segregation on interstate trains and buses, she was pivotal in integrating the Red Cross. In 1940, Mary McLeod Bethune was elected as the national vice-president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She held this executive position until her passing. As an advisor to President Roosevelt, in 1942, she assisted Secretary of War, Harry L. Stimson, in choosing officer candidates for the U.S. Women’s Army Corp (WAC). The purpose of Bethune and others on the advisory board was to greater ensure that the corp was racially integrated. As the assistant director of the Women’s Army Corps, she organized the women’s officer candidate schools and lobbied for the inclusion of African-American women, including Charity Adams Earley, into the military (see ISSUE #3).

Charity Adams Earley, the first African-American woman to become an officer in WAC, commanded the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, the first battalion of African-American women to serve overseas. At the conclusion of World War II, she had earned the rank of “Lieutenant Colonel”, making her the highest ranking African-American women in the U.S. Army at that time. In her reflections expressed in her autobiography, One Woman’s Army: A Black Officer Remembers the WAC, Adams Earley praised Bethune for her efforts to provide Blacks with access to greater opportunities for development. Bethune was amazingly inspiring to many Blacks. Her appeal to Black women who wanted more for a career than teaching, nursing and performing domestic work as well as to those who had been formally educated was strongly heeded.

Mary McLeod Bethune also was the only African-American woman member of the “The Black Cabinet”, prominent African-Americans who informally advised President Roosevelt on affairs in the Black community. She used her access to the Roosevelts to create a coalition of leaders from Black organizations called the Federal Council of Negro Affairs, which came to be known as “The Black Cabinet”. Like Bethune, these accomplished Blacks who had been appointed to federal positions informally advised the Roosevelt administration on issues facing African-Americans. However, unlike Bethune, these “advisers”, were all men.

For many Blacks, the creation of this first collective of Black people working in higher positions in government illustrated, through action, that the Roosevelt administration cared about the issues of Blacks. As advisers, they did not directly create public policy but they were respected by Black voters who wanted strong leadership, influenced political appointments and disbursed funds to organizations that would benefit Black people. In 1945, Bethune, appointed by President Truman, was the only woman “of color” at the inaugural conference of the United Nations. Representing the NAACP, she was accompanied by W.E.B. DuBois and Walter White, who were also African-American. During her lifetime, Bethune would advise four presidents: Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1944, Bethune co-founded, along with Frederick Patterson and William J. Trent, the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), The UNCF is a program that provides numerous scholarships of varying kinds, employment opportunities and mentorships to African American and minority students who attend any of the thirty-seven historically Black colleges and universities. William J. Trent aided Patterson and Bethune in raising money for UNCF. Having started the fund in 1944, by 1964, Trent had raised over fifty million (USD).

In 1949, Mary McLeod Bethune became the first woman to be awarded the Medal of Honor and Merit, the highest award given in Haiti. In Liberia, she received the honor of Commander of the Order of the Star of Africa. Additionally, Bethune regularly wrote for the leading African American newspapers, the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier, in which she invested.

Retiring in Florida, Bethune, an astute businesswoman, co-owned a Daytona, Florida resort, the Welricha Motel and co-founded the Central Life Insurance Company of Tampa. Because of racial segregation, it was illegal for Blacks to visit the beach. Bethune and several other Blacks invested in Paradise Beach, a 2-mile area of beachfront property. Although Whites could visit, Bethune and her business partners sold parts of the land only to African-Americans. Paradise Beach would be renamed “Bethune-Volusia Beach” in her honor.

On May 18, 1955, Mary McLeod Bethune passed away from a heart attack; she was seventy-nine years old. News of her death was accompanied by tributes in newspapers, significantly those that were African-American, throughout the country. As Ruffin II observed, Bethune “lived long enough to see the U.S. Supreme Court strike down de jure school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education but she died seven months before the beginning of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which ushered in the modern Civil Rights Movement, which was in part inspired by her activism.”

A true icon of inspiration, Bethune has been celebrated with many accolades and awards, including the Spingarn Medal, an annual award gifted by the NAACP to an African-American for their outstanding achievement. She was awarded this medal in 1935 for her “outstanding leadership in service and education”. Bethune’s vibrant legacy was honored by an induction into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1973; a memorial sculpture of her erected in Lincoln Park of Washington D.C. in 1974; and a postage stamp commissioned by the U.S. Postal Service was issued in salute to her in 1985. Her final residence, the former headquarters of NCNW, was purchased by the U.S. Park Service. It is presently known as the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site.

(No copyright infringement intended).

While these awards are wonderful, the power, brilliance, humility and beauty of Bethune was that she readily gave of herself to uplift others. In the biography of Bethune on the official website of Bethune-Cookman University (as it is now known), it states, “While she gave counsel to presidents and made connections with America’s elite, Mary McLeod Bethune was readily accessible to average men and women and the college students that she mothered and mentored. Her access to people of power and privilege was never something she used to benefit herself. It was always an opportunity to gain access for those shut out of opportunities in our society. She enlisted leaders of government and industry to support her vision and dreams for her school in Daytona Beach, for social justice and positive change for all.”

Her words, engraved on the sculpture of her in Lincoln Park, wisely advise and beautifully inspire, “I leave you love. I leave you hope. I leave you the challenge of developing confidence in one another. I leave you a thirst for education. I leave you a respect for the use of power. I leave you faith. I leave you racial dignity. I leave you a desire to live harmoniously with your fellow men. I leave you, finally, a responsibility to our young people.”

“If we accept and acquiesce in the face of discrimination, we accept the responsibility ourselves. We should, therefore, protest openly everything … that smacks of discrimination or slander.”

~ Mary McLeod Bethune