“I don’t know of any man in the sport that worked any harder than he did or accomplished more than he did with what he had … He built a lot of respect … More important, he helped to open many minds and heart s… He was not as fortunate as some of us as to the type of equipment he had to drive. But he went out there and toiled and made it work and won – not only won races but won the hearts of people around the world.”

~ Ned Jarrett, Two-time NASCAR Grand National Series champion

Wendell Oliver Scott was born on August 29, 1921 in Danville, Virginia. His father, William, was atypical of many who lived in Danville, as he worked as a driver and mechanic for affluent Whites. Most residents, especially African-Americans, labored in the cotton mills and tobacco-processing plants that were prevalent throughout the Southern small town.

Wendell greatly admired his father, both learning the skills needed to successfully perform auto mechanics and modeling the audacious driving expertise of his father. From a young age, Wendell dominated anything with wheels, whether it be a bicycle, roller skates or an automobile. His daredevil style often brought comparisons to the bold fashion of his father. Sadly, William had a gambling issue which led to the destruction of his marital relationship. The stress of his parents’ divorce was so great that it impacted Wendell’s speech, causing him to stutter.

Also straining was the Scott family’s need for economic support, prompting Wendell to drop out of high school during the eleventh grade. In order to assist his family, he worked several jobs. He also served for three years as a motor pool mechanic in the European Theater with the U.S. Army during World War II. After completing his term, Scott returned to Virginia where he continued to work with automobiles. He opened his own shop to repair cars and often drove a taxicab for further financial support. This support was greater needed when he, in 1943, married Mary Coles; they would be blessed to have seven children.

However, what is most interesting is that Wendell Scott built and drove his own vehicles selling and delivering moonshine whiskey. Because this was dangerous and illegal, Scott had to be an exceptional driver. According to the profile “Biography: Wendell Scott” at the website of WDKX, he “developed impeccable driving skills and he spent most of his career as a moonshine runner outrunning cops.” Scott was so accomplished that he was captured only one time. After being caught in 1949, he received a lenient probation of three years and continued to haul moonshine.

Around 1950, Wendell Scott was viewing local automobile races and decided to enter. At that time, the races in Danville were managed by Dixie Circuit, a competitor of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR). Because it was less prominent, Circuit officials decided to recruit African-American drivers to gain greater audiences. In “NASCAR Still Owes Wendell Scott a Trophy for his 1963 Grand National Victory” at Autoweek.com, writer Al Pearce shared, “That well-deserved reputation as a bootlegger had its upside: When promoters at the local speedway wanted a Black driver to attract minority fans, the Danville police unhesitatingly steered them toward Scott’s garage on Keens Mill Road.”

Wendell Scott took up their initiative and with Hiram Kincaid, an African-American mechanic who worked with White professional drivers, such as Ned Jarrett, towed Scott’s cart to a NASCAR event in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Wendell Scott was summarily refused entry because he was a Black man. Several days later in High Point, North Carolina, he was met with the same denial, based on racial discrimination. In the WDKX profile on Scott, it is written, “While he was gearing up for the race, his friends filled the stands, but this took the officials by surprise because they thought he was White. It wasn’t until they saw his friends did they realize Scott was Black. So the track officials decided he couldn’t enter the race because he was Black. This experience left Scott in tears, but he didn’t let that stop him either.”

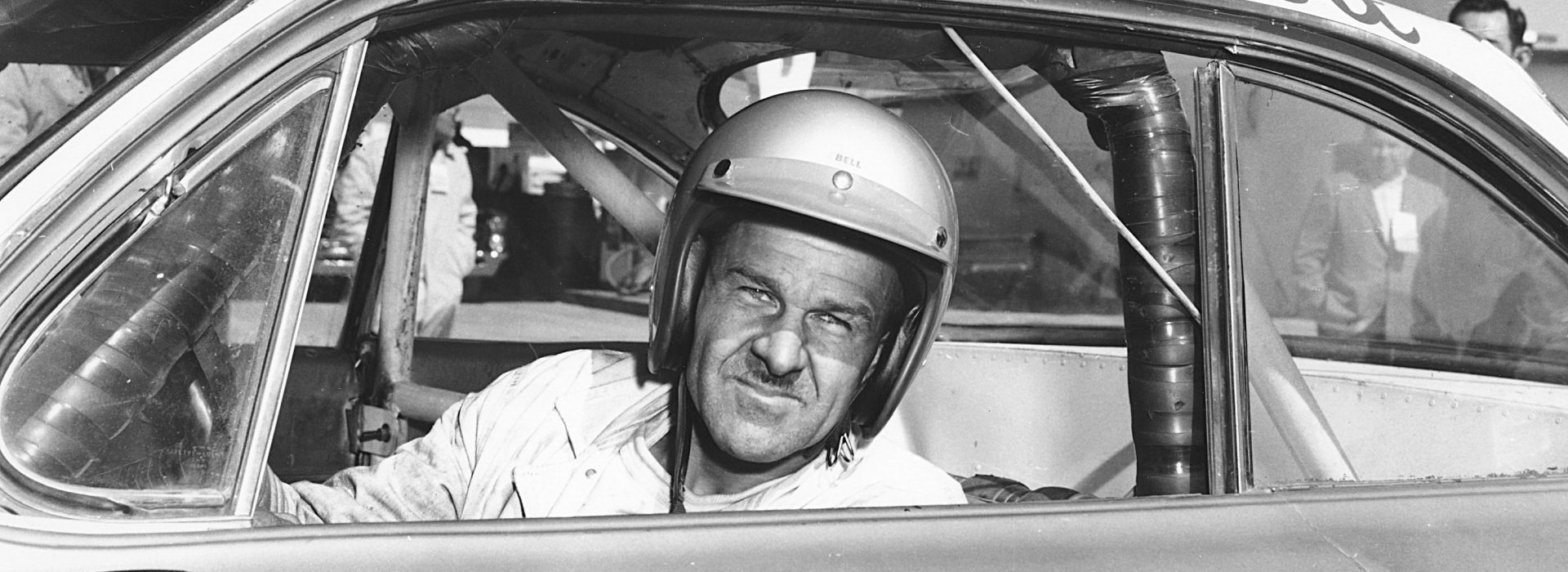

This would be a common occurrence with NASCAR races for Scott so he decided to enter racing events of the Dixie Circuit and other speedways. On May 23, 1952, Wendell Scott broke the color line of stock car racing when he drove his Ford in an amateur race at the Danville Fairground. Finishing third place and awarded $50, he was convinced that racing was indeed his vocation.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Over the next two decades, Wendell Scott faced constant opposition, including racial slurs and drivers wrecking into his car purposely, as he competed in races throughout the segregated South. He, his family and his crew were denied access to public accommodations including hotels and restaurants. Scott had to depend on himself and trained his children to work with him in repairing and tuning his cars, which were often bought from other drivers. In the article, “The Pioneering Career of Wendell Scott” by Tom Jensen at the NASCAR Hall of Fame website, Wendell Scott’s “mechanical acumen, relentless determination and ability to stretch a dollar allowed him to compete successfully with used cars and parts against teams with far more money and resources.”

However, a determined Scott received his NASCAR license from steward Mike Poston circa 1953 after towing his racecar to a NASCAR event at the Richmond Speedway in Virginia. Despite his wins and the gain of many Black and, now, White fans, most officials and executives at NASCAR still did not want Wendell Scott as a part of their organization.

Another example of the racism Scott faced occurred in 1954 at a racing event in Lynchburg, Virginia. For the first, time, Wendell Scott met for Bill France, the founder and president of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing. In their meeting, the exceptional driver shared that the promotor of a race in Raleigh, North Carolina refused to pay for his petrol though he had given all the White drivers monies. Yet justice was attained in this instance. According to author Brian Donovan in Hard Driving: The Wendell Scott Story, Scott praised France, who “immediately pulled some money out of his pocket and assured Scott that NASCAR would never treat him with prejudice. ‘He let me know my color didn’t have anything to do with anything … You’re a NASCAR member, and as of now you will always be treated as a NASCAR member.’ And instead of giving me fifteen dollars, he reached in his pocket and gave me thirty dollars.”

While those in Daytona Beach leading NASCAR were upset, Scott went on to win numerous races in Virginia and North Carolina, including the Virginia NASCAR Sportsman Championship in 1960. At this point in his career, he was at long last able to compete against elite drivers, such as Junior Johnson, Fred Lorenzen, David Pearson, Joe Weatherly and Rex White, all who would later be inducted into NASCAR’s Hall of Fame.

On March 4, 1961, Wendell Scott became the first African-American to compete in NASCAR’s Grand National Series at Piedmont Interstate Fairgrounds in Spartanburg, South Carolina. On the half-mile dirt track, he earned $50 after finishing an engine-related 17th in an 18-car race. Though Scott was the recipient of the most points for a debutant that year, the Rookie of the Year award was given to Woodie Wilson, a White driver. In the Autoweek article, Pearce detailed, “Despite far better statistics in every meaningful on-track category, he lost the 1961 Rookie of the Year award to White driver Woodie Wilson. Scott started 23 races that year and had five top-1o finishes, while Wilson started just five races and managed one top-10.”

Continuing to compete, on December 1, 1963, Wendell Scott became the first African-American driver to win the Grand National Series race, the premier level of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing!

(No copyright infringement intended).

He drove a Bel Air automobile that he bought from his good friend and future Hall of Fame inductee, Ned Jarrett, a White racer. Occurring at Jacksonville Speedway Park in Florida, there was a dispute over scoring that lasted two hours, most likely fueled by racism. Initially, second-place driver Buck Baker, who was White, was announced as the event’s winner. Their proclamation immediately drew outrage, as 2 laps driven by Scott in the 100-lap main event hadn’t even been scored. Those uncounted laps actually placed Wendell Scott far in front of the other racers. One of these drivers included another future Hall of Famer Richard Petty, who lagged twenty-five laps behind due to his poor performing vehicle. He earned fifth place.

It took the national stock car racing association two years to, ultimately crown Wendell Scott as the winner. After NASCAR overturned their initial scoring, the Black auto racing pioneer and champion was given his winnings of $1,000. However, the trophy had mysteriously “disappeared” in the brouhaha. It had been given to Baker in victory lane but could not be found afterward. For decades, Wendell Scott and his family would engage in efforts to get what rightfully belonged to him.

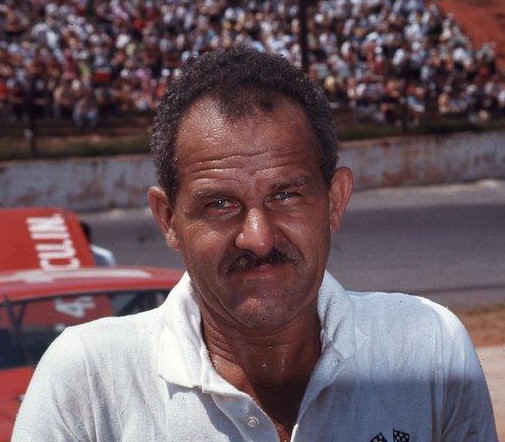

Wendell Scott, operating on a shoe-string budget while battling racism, continued to excel. He consistently ranked high, finishing 12th in points in 1964 and 11th in points in 1965. His career best was at 6th in points in 1966, initiating his streak of four Top Ten rankings including at 10th in points in 1967, 9th in points in 1968 and 1969. In the 1966 season, according to the NASCAR Hall of Fame website, Wendell Scott “finished higher in the NASACAR year-end standings than seven other drivers who were eventually inducted into the Hall of Fame.” Pearce provided further support of Scott’s accomplishments, writing, “He made 495 starts between that debut and October 1973, mostly in homemade or second-hand cars well past their prime. In addition to the Jacksonville victory, he had one pole, 20 top-fives, 147 top-10s and top-10 points seasons in 1966, 1967, 1968 and 1969.” Despite his accomplishments, Scott was never commercially-sponsored.

In May 1973, Wendell Scott suffered critical injuries when his top car, a 1971 Mercury Montego, was destroyed in a racing event at Talladega, Alabama. He would be hospitalized for weeks. In October, he returned to race a final time in Charlotte, North Carolina after having missed the following sixteen races. He finished in 12th place. Pearce reflected on the overall weariness, dedication and bravery of Scott, championing, “Financially, emotionally and physically drained, he retired after that October’s 500-miler at Charlotte. He was a well-worn 51, beloved and respected by almost everyone in the sport. Once scorned by fans and barred from NASCAR because of his skin color, he had won them over with his skill, grace and determination in the face of unimaginable odds.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

On December 23, 1990, Wendell Scott passed away from spinal cancer in Danville, Virginia; he was sixty-nine years old. In his professional career, he achieved one win and 147 Top Ten finishes in his 495 Grand National starts. He died having never received the trophy for his 1963 victory that rendered him as the first African-American to win a NASCAR Grand National event.

Since his entry into what is presently the Cup series of NASCAR, only seven other Black drivers have raced in it. They are Elias Bowie, Charlie Scott, George Wiltshire, Randy Bethea, Willy T. Ribbs, Bill Lester and Darrell “Bubba” Wallace, Jr., who recently led a campaign calling for Wendell Scott to be inducted into its Hall of Fame. Wallace Jr., the second African-American driver in to win in NASCAR’s top 3 series, has also been a victim of racial discrimination and harassment during his tenure of racing.

His rich legacy includes being memorialized in media and tributes. Characters based on Wendell Scott are featured in Greased Lightening (1977), which starred Richard Pryor; Cars 3 (2017) by Pixar; Timeless television series episode, “The Darlington 500” (2018) as well as “The Ballad of Wendell Scott” (1986) by Danville native, Mojo Nixon. He has also been highlighted in The World’s Number One, Flat-Out, All-Time Great Stock Car Racing Book (1975) by author and journalist Jerry Bledsoe and featured in the rare, John W. Warner documentary, American Stock: The Golden Era of NASCAR: 1936-to-1971 (2005).

The City of Danville paid tribute to him by naming a street in his honor and also installed a historical marker in 2013. In “Danville to Get Historical Marker Honoring NASCAR Racer Wendell Scott Sr.” printed by WSLS-TV, the marker, as per the Department of Historic Resources, reads, “Persevering over prejudice and discrimination, Scott broke racial barriers in NASCAR, with a 13-year career that included 20 top five and 147 top ten finishes.”

He has been inducted into the Jacksonville Stock Car Racing Hall of Fame (1994), the International Motorsports Hall of Fame (1999) and the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame and Museum (2000).

In 2010, the family of Wendell Scott finally received a replica trophy from Jacksonville Stock Car Racing Hall of Fame. This was forty-seven years after the race and twenty years after Scott had passed.

In “Wendell Scott’s Family Gets Long-lost Trophy and Closure” by Don Coble for the Florida Times-Union, the journalist reported on resolution. Ronnie Rohn, president of the Hall, shared their struggle to successfully locate the original trophy and their follow-up efforts to create a trophy that would be authentic to the one Wendell Scott should have received. The Hall also built a replica of Scott’s signature sky-blue Chevrolet, prominently featuring his car number “34” emblazoned on it, to honor the Black racing trailblazer.

(No copyright infringement intended).

At the dedication to Scott and gifting of the trophy, the Scott family was very emotional. Included in attendance was his widow, Mary; sons Wendell Jr. and Franklin; and his daughter, Sybil. In the Coble article, he reported that Sybil Scott offered, “This has been a journey for us … The effort you all have put forth to make this night what it has been – there simply are no words that can ever express what we really feel, but we hope our presence here tonight will, in part, show that we are truly grateful. We do realize you have put forth a lot of effort, that you all will continue to have safe racing and the respect you have shown to our father will forever be embedded in our hearts.” After the ceremony, Wendell Jr. and Franklin took the trophy to their father’s grave. As Wendell Jr. affirmed, “He will know it … He wanted that trophy so much. Now he has it.”

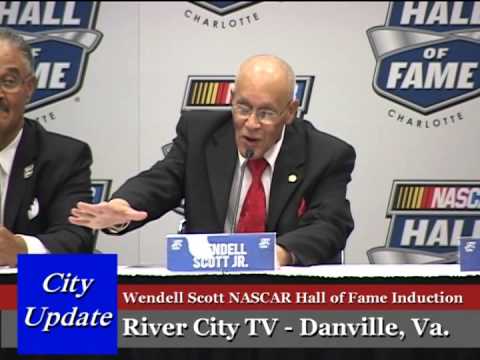

Wendell Scott was finally inducted into the National Association for Auto Stock Car Racing in 2015. His grandson, Warrick Scott, expounded that NASCAR has a responsibility in honoring his acclaimed grandfather. In the Autoweek article, he proffered, “How many racers worried about getting shot by a sniper? How many worried about a dark roadblock 60 miles down the road late at night? How many worried about the KKK? Or getting run off the road at night? My grandfather was a racing genius and we’re not going to accept that his legacy will go unfulfilled … Even in 2020 we’ve had a much harder time establishing recognition, opportunities and respect for Wendell’s contributions … In a world that is media-centric and often facilitated by inaccuracies and half-truths, there is an obligation to uphold integrity. I believe it’s time for NASCAR to rise to the occasion by changing the narrative of an unpleasant past involving my grandfather and NASCAR.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Warrick further affirmed about his grandfather’s incredible work, which brought “… diversity in racing, so NASCAR needs to tell that story through the lens of Wendell Scott. He gave people hope because he had a big heart for everyone. He had more love in his heart than (his enemies) had hate in theirs. He did as much for race relations in the South as Dr. (Martin Luther) King.”

“Once I found out what it was like, racing was all I wanted to do as long as I could make a decent living out of it … I’m no different from most other people who’re doing what they like to do.”

~ Wendell Scott

For greater enlightenment...

-

The Golden Era of NASCAR: Wendell Scott

-

Wendell Scott: A Race Story

-

Wendell Scott

-

Wendell Scott's son, grandson discuss his career and legacy | Coffee With Kyle | Motorsports on NBC

-

Wendell Scott Hall of Fame Induction

-

Inside NASCAR Wendell Scott Part 1

-

Inside NASCAR Wendell Scott Part 2

-

Greased Lightning - Trailer

-

Driven