The Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site was founded to honor the many contributions African-Americans enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II made to American history and society. These African-Americans, called “Tuskegee Airmen”, fought extreme racial discrimination and became one of the most highly-respected military groups in American history. During the course of the war, 66 out of the 450 Tuskegee Airmen died in battle. The airmen engaged and defeated Messerschmitt Me 262s, the first operational jet fighters, and were awarded a total of eight-hundred and fifty medals!

The extensive achievements of the Tuskegee Airmen disproved the racist propaganda, rhetoric, social customs, laws and even actions levied against Blacks in the military. The accomplishments of the Tuskegee Airmen greatly influenced the U.S. military’s decision to end racial segregation within, thus, fully integrating all its branches.

The Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, operated by the National Park Service, is located in Tuskegee, Alabama, on Moton Field. Moton Field was selected because it was the only primary facility for flight training for African-American pilot candidates. The candidates who passed the intense aviation training became known as the Tuskegee Airmen and comprised the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group. However, “Tuskegee Airmen” actually references all, including bombardiers, control tower operators and dispatchers, instructors, maintenance workers, mechanics, medical personnel, meteorologists, navigators, parachute riggers, radio operators, supply personnel and technicians, who were involved in the “Tuskegee Experience” program.

In 1940, the U.S. Army Air Corps developed the “Tuskegee Experience” program that trained African-Americans to fly as well as maintain combat aircraft. Prior to 1940, Blacks were excluded from flying as pilots in the U.S. military. As per the National Park Service website content on the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, “The Tuskegee Airmen (Airmen) sprang from an experiment conducted by the US Army Air Corps (Army Air Forces) to see if Negroes (primarily African-Americans) had the mental and physical capabilities to lead, fly military aircraft, and the courage to fight in war.”

However, this exclusion was lifted, primarily due to demands by civil rights organizations, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the Black press, most notably, the Chicago Defender. As a result of this lift, an all African-American squadron was formed in 1941 and its base was in Tuskegee, Alabama.

Tuskegee Institute was selected by the U.S. Army Air Corps to train this new squadron for several reasons. The Institute had exceptional engineering and technical instructors, newly-constructed facilities that greatly supported aeronautical training and the essential climate that allowed for flying, regardless of the season. The students of the inaugural Civilian Pilot Training Program completed their program in May 1940. Because of its success, the Tuskegee program was greater developed and it became the training ground for African-American aviation during World War II.

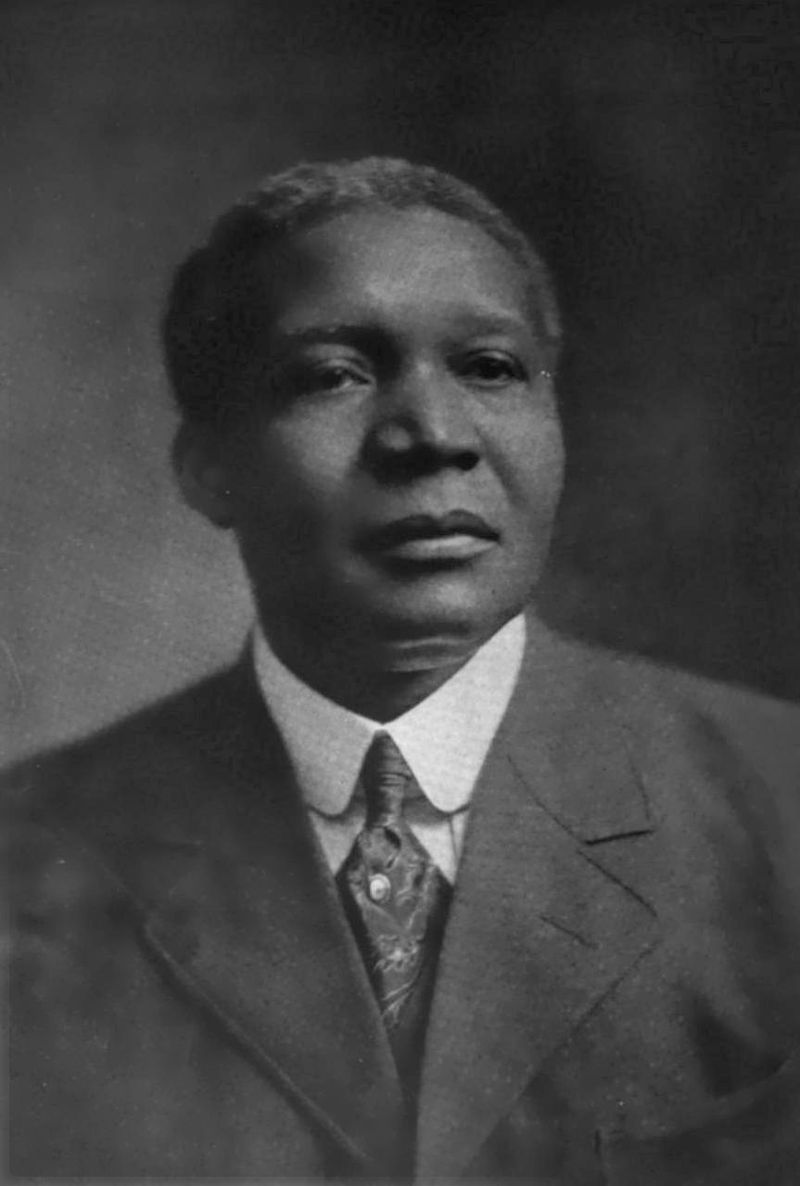

The field was constructed in 1941 and named in tribute to Robert Russa Moton, who had passed the previous year. Moton was the second president, after founder Booker T. Washington, of Tuskegee Institute, a historically Black university. Moton served as the Institute’s administrator for twenty years.

Funding for the field’s construction was granted from the Julius Rosenwald Fund; it also, in a contract with the U.S. military, provided primary flight training. Staff from Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama assisted in mapping out what would be Moton Field. Many of the structures were designed by architect Edward C. Miller and engineer G. L. Washington and much of the construction of the flight school’s facilities was supervised under contractor and engineer, Archie A. Alexander. Laborers and skilled workers from Tuskegee Institute worked to complete the construction of Moton Field in order for flight training to begin as scheduled.

According to the National Park Services website, “The Army Air Corps assigned officers to oversee the training at Tuskegee Institute/Moton Field. They furnished cadets with textbooks, flying clothes, parachutes, and mechanic suits. Tuskegee Institute, the civilian contractor, provided facilities for the aircraft and personnel, including quarters and a mess for the cadets, hangars and maintenance shops, and offices for Air Corps personnel, flight instructors, ground school instructors, and mechanics. Tuskegee Institute was one of the very few American institutions to own, develop, and control facilities for military flight instruction.”

Aside from training at Moton Field, the Tuskegee Airmen also trained for flight at Calabee Flight Strip, Hardaway Auxiliary Field and Kennedy Auxiliary Field. It was at Kennedy Field that First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was flown in an aircraft piloted by C. Alfred “Chief” Anderson, the chief instructor pilot at Tuskegee Institute. The flight of First Lady Roosevelt was highly significant, as she, a trustee of the Julius Rosenwald Fund, was pivotal in securing the funding for the construction of Moton Field at Tuskegee Institute.

At Moton Field were military personnel who were not African-American; Caribbean Islanders, Caucasian, Indigenous Americans and Latinx as well as mixed ancestry were stationed in Tuskegee.

There were also women included in the Tuskegee Experience and they worked alongside, according to its page featured on the National Park Service website, “their male counterparts as mechanics, gate guards, control tower operators, did aircraft body work, secretaries, and clerks. There were three permanent female parachute riggers whose responsibility was to train the hundreds of cadets that filed through the program on the appropriate way to pack and maintain parachutes. Gertrude Anderson served as Assistant to G.L. Washington at Kennedy Field, where Tuskegee’s Civilian Pilot Training Program was held. She assumed responsibility for continued operation of the airfield when Washington was transferred to Tuskegee Army Air Field.”

Despite these advancements, the Black men and women still faced obstacles, including The Freedom Field Mutiny. In 1945, the U.S. Army Air Corp created the 477th Bombardment Group, which was all-Negro (Black); it was assigned to Selfridge Field in Michigan. When a Negro officer applied for membership to the Officers’ Club on base, his request was denied by General Frank O. Hunter who refused to allow racial mixing on any of the bases that he commanded.

In order to counter this, Congress allotted $75,000 to build an all-Negro officer’s club but the 477th was transferred to Godman Field in Kentucky before the club was even built. The group was then transferred to Freeman Field in Seymour, Indiana. Freeman Field was under the command of Colonel Robert Selway, who strictly enforced racial segregation and sanctioned racial discrimination. This discrimination included the creation of a base protocol that identified the 400 Negro officers as “trainees” and their 250 White counterparts were listed as “instructors”.

The Negro “trainees” were assigned to Officers’ Club #1, which was an old, dilapidated building and the White “instructors” were assigned to Officers’ Club #2, which was a newly-constructed, fully-functioning facility.

On April 5, 1945, a group of Black officers, led by former labor leader, Lieutenant Coleman Young, requested entry into Officers’ Club #2. They were denied and within thirty minutes, another group of Black officers were also denied entry. However, Lt. Marsden Thompson, followed by the others, entered anyway and without incident.

On April 6, more than sixty Black officers were arrested for entering or attempting to enter Officers’ Club #2. According to the National Park Service website, the arrests “… prompted a base order, called Regulation 85-2, to be issued from Gen. Hunter and Col. Selway officially assigning officers to club by race and specifying strict segregation of housing, dining halls, and officer’s clubs. It also stated that any violation would result in confinement. Selway called all the Black officers assigned at Freeman Field together and ordered them to sign a statement that they had read and agreed with Regulation 85-2. This was done despite US Army Regulation 210-10 which strictly forbade segregation of public facilities on military installations, thereby requiring officer’s clubs to be open to all, regardless of race.”

One hundred and one Black officers refused to sign the unconstitutional, hence, illegal, document. Their refusal to obey a direct order from a superior officer during the time of war could have been punishable by death. The arrested Negro officers were transferred to Godman Field and placed under guard of armed soldiers and attack dogs. Ironically, these Black soldiers of the U.S. Army Air Corps were treated worse than German prisoners of war, who had complete freedom of movement on the base. There are also accounts of the Germans’ ridicule against the Black officers and how they were outrageously treated by their own country, the United States, for whom they fought.

Because of the terrible news coverage, led by the Black press, labor unions and Congress, that the military was receiving, U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall issued orders to release the officers on April 23, 1941. All of the Black officers were released but General Hunter included a letter of reprimand in each of their files.

Three of the officers were held for trial. While two were fined and released, Lieutenant Roger Terry, was court martialed, fined, stripped of his rank, and dishonorably discharged from the Army for “jostling”.

Fortunately, Colonel Selway was relieved of his command, and was replaced with Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, Jr, who was a graduate of the first class of Tuskegee Airmen. Two of the 477th bomb squadrons were inactivated, and the 99th fighter squadron was added to the 477th becoming the 477th Composite Group. In 1946, the 477th Composite Group was reassigned to Lockbourne Air Force Base in Ohio and deactivated in 1947.

Almost fifty years later, President William H. Clinton, in 1995, had the reprimands removed from the permanent files of fifteen of the officers and the U.S. Army agreed to remove the reprimands of the remaining eighty-six upon request. Terry received a full pardon, refund of his fine and restoration of rank.

The Freeman Field Mutiny would aid in laying the foundation for the non-violent protests, including sit-ins, of the Civil Rights Movement during the 1950s and 1960s.

Visitors to the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site will learn about these experiences and more! The Tuskegee Airmen were, indeed, incredible, and interesting items about them, as detailed on History.Com, include:

- “The Tuskegee Airmen, who flew combat missions in World War II, were also known by the nickname, ‘Red Tails’, for the distinctive red paint on the tails of their P-51s.

- First all-Black aerial units in the Army Air Forces, active during World War II. In total, about 1,000 pilots were trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field. Approximately 335 pilots [were] deployed to the war in Europe.

- Trained at Tuskegee Institute/Moton Field in Alabama from 1941-1946.

- They served in the 332nd Fighter Group as the 99th, the 100th, the 301st and the 302nd Fighter Squadrons under the 12th and 15th Air Forces in the European Theater of Operations. The 447th Bombardment Group was comprised of the 616th, 617th, 618th and 619th Bombardment Squadrons. They were also assisted by important maintenance and support units.

Achievements

- The Tuskegee Airmen fighter units thrived in the skies. Their squadrons flew more than 15,000 sorties on 1,500 missions and shot down 112 German aircrafts.

- Together, they earned one Legion of Merit, one Silver Star, several Distinguished Unit Citations, 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses, many Purple Heart medals, 14 Bronze Stars and 744 Air Medals.

- In 2007, as a group they received a Congressional Gold Medal for their service during World War II. Like many all-Black units, their excellence was not officially recognized until years later.”

Guests may visit the museums at Hangar #1 and Hangar #2 of Moton Field. Tours may be taken independently but group tours for ten or more are available. The site can accommodate special needs but please coordinate with the site personnel prior to the visit in order to best enjoy the tour experience.

There are also educational components, including curriculum materials and lesson plans for educators, and professional development, such as the Teacher-Ranger-Teacher (TRT) program, available at this site. The TRT program, according to the National Park Service site, “…is a national program that links National Park Service sites to classrooms by bringing teachers into the parks to work during the summer. The program enables teachers to bring their classroom expertise to park programs. In return, teachers return to the classroom with a new set of experiences and appreciation for local resources to share with their students.”

Presently, the museums at Moton Field are open Monday through Saturday, from 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., CST. They are closed for Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s Day.