Every time I visit an area while on holiday, I love to discover or further “investigate” sites that have significance in Black culture. These sites range from cultural centers, museums and theatres to galleries, restaurants and parks. While matriculating Columbia University in the City of New York for my graduate degree in African-American Studies, I loved my good fortune of living in the Harlem community, because there is such a saturation and celebration of Black culture. Obviously, there is a great deal of Black culture to experience in New York City and I feel that one of the many sites that any person interested in this culture should visit is the African Burial Ground Monument, a National Historic Landmark (1993) and National Monument (2006). This monument is designed to connect African-Americans with their African ancestors.

The discovery of this burial ground is of critical importance, historically, sociologically and genetically. It gives insight to the Africans who were integral to the creation of New York City, as both a colonial possession during European imperialism and a member of the United States. To highlight the significance of this find, it should be noted that at the start of the American Revolution, New York City was the second largest slave-holding city in America, the first being Charleston, South Carolina.

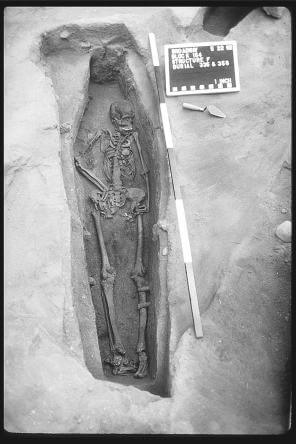

This monument is a portion of the oldest known African-American cemetery in New York City and contains the skeletal remains of more than 419 Africans who lived there during the City’s colonial period of the 17th and 18th centuries. Many of these remains are of children under the age of 12. Located at African Burial Ground Way (known as Elk Street outside the monument area) and Duane Street in Lower Manhattan, the cemetary’s main building is the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway. It stretches across approximately 6 acres. According to the National Park Services, the federal agency under whose auspices this site is governed, “… currently, the Burial Ground is the nation’s earliest and largest African burial ground in the United States”!

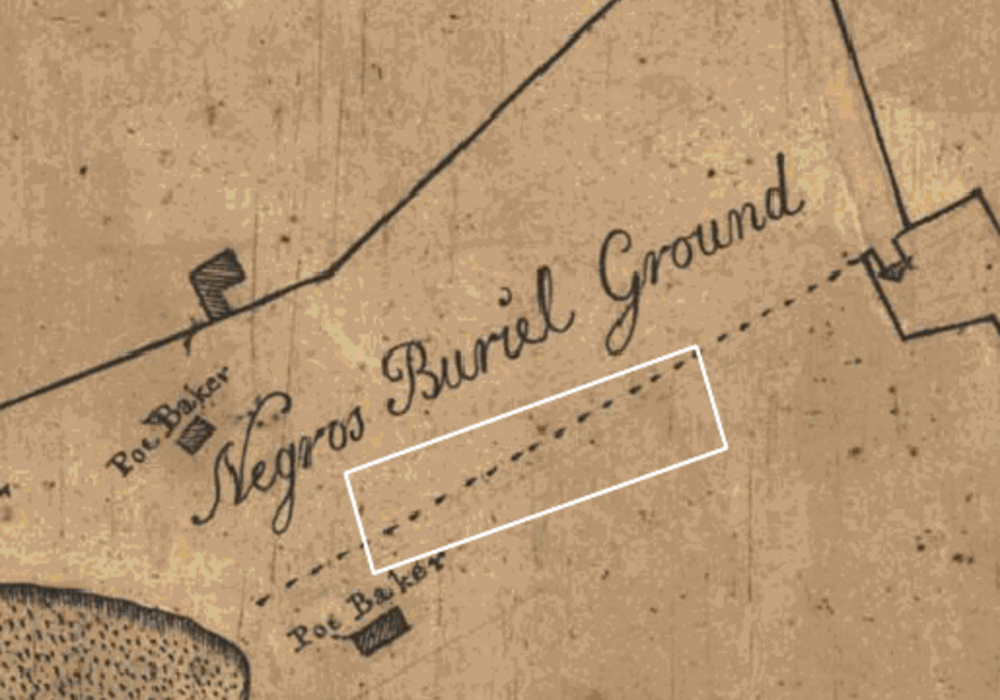

Known formerly as the “Negroes Buriel Ground”, the cemetery contains the intact skeletal remains of greater than 15, 000 Africans and their American-born descendants; some were free but many more had been enslaved. These Africans lived in New York when it was a colony, first of the Dutch Republic, then after, England. The dates for the burials span from the 1630s to 1795. Due to the institution of slavery, its treacherous dependency on free labor and accompanying tragic results for those enslaved, the Africans comprised approximately 25 percent of the population in New York City, rendering it one of America’s largest urban areas that practiced slavery at that time.

This cemetery site was discovered during an excavation of the area surrounding 290 Broadway. In 1991, a project for a 34-story federal building, overseen by the General Services Administration, was to be constructed there. Because it received federal funding, one of the mandates required for its construction was that it had to comply with directives of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. To comply with this Act, a study was undertaken to assess any potential archaeological and cultural damage. When archaeologists discovered the skeletal remains of the Africans just 30 feet below the street level of Broadway, discussions and negotiations were held among the Administration; professionals, including anthropologists, geneticists, historians, political scientists and sociologists; and community activists.

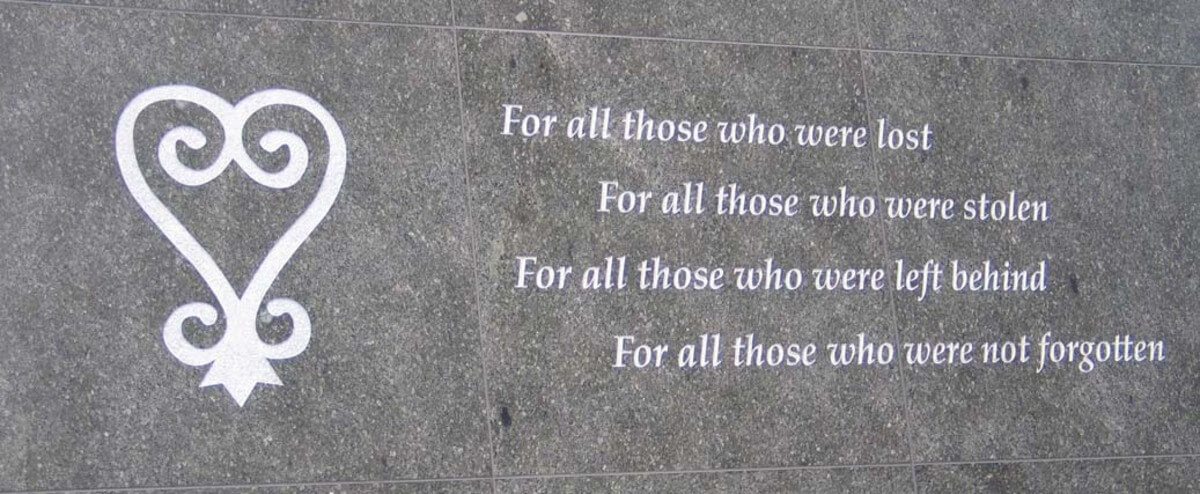

In 1993, the Secretary of the Interior declared the “Negroes Buriel Ground” as a national historic landmark because it, according to the federal designation, holds “exceptional value or quality in illustrating or interpreting the heritage of the United States.” In 2003, federal funds were appropriated to create the memorial for the site and the federal courthouse was redesigned. The following year, architects Rodney Leon and Nicole Hollant-Denis won the bid competition sponsored by the General Services Administration and designed the site memorial that was dedicated on October 5, 2007. The monument is a 25-foot structure that, according to Leon, includes “a map of the Atlantic area within the ‘Circle of Diaspora.’” Constructed of stone, primarily granite, from Africa and North America, the monument contains tributes to African heritage. These tributes include The Middle Passage as well as The Door of No Return. The Door of No Return, located at The House of Slaves on Gorée Island, off the coast of Dakar, Senegal, is, according to BBC News, “a name given to slave ports set up for involvement with the age-old local institution of slavery on the coast of West Africa, from which so many people were transported after sale by their native chiefs, never to see their homeland again.”

At this site, visitors may learn more about the lives of Africans in early New York. Guests can contrasts these Africans’ lives with those of their African brothers and sisters who, at the time, lived from the Chesapeake Bay area to the American South. There is a visitor center, which includes the permanent exhibit, “Reclaiming Our History”; a theatre; an interpretive center; a research library; gallery and gift shop. Immensely powerful are the exhibits of the reinternment of the remains of the Africans as well as the diverse symbology and its accompanying history engraved in the monument.