Trains

Upon their creation, trains were the ultimate in technology, speed & glamour. In order to greater transport freight & passengers, train companies competed for customers. With increased access to travel, especially cross country, came the demand for greater comfort.

Entrepreneur George Pullman of Illinois sought to meet this demand by creating high quality coaches & luxury railroad cars for lease to railroad companies. They were so luxurious that they were referred to as “rolling hotels on wheels” & “traveling Pullman” meant to travel in high style!

However, it was not just the cars that prompted the sale of these expensive tickets; it was the service of the Pullman porters, who, as service personnel, was locked in the lease to the railroad companies.

With the Panic of 1873, followed by the Depression of 1893, Pullman lowered wages even more, DRASTICALLY impacting Black workers in his company, & refused to lower rent in Pullman, his housing community of White workers. His refusal prompted the Pullman strike of 1894. Riots broke out throughout the country but Pullman porters were not involved in the strike. In fact, they continued to work ceaselessly!

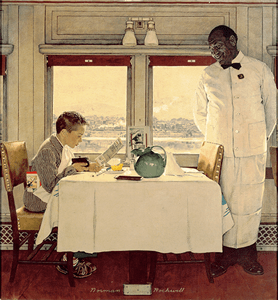

Pullman intended his railroad cars to cater to those of the upper echelon & his cars were celebrated for their luxury and glamour. The men who were hired as conductors and ticket sellers were White; those who provided service as the porters were Black men.

In the beginning, these porters had been formerly enslaved Black men who had been specifically recruited by the Pullman company. The selection of these Black men was due to their prior experience of providing “service” as well as the Whites’ desire, in wanting to cling to the personal & social customs of slavery, to be catered to and waited on by Blacks still, despite slavery ending. According to Larry Tye, author of Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class, luxury sleeper car innovator George Pullman had sought these African-American men purposely to cater to the demands of wealthy White travelers because “they had spent their entire life doing what their masters had told them & what George Pullman envisioned was that when they went out on the rail cars, they would do the same things for his customers.”

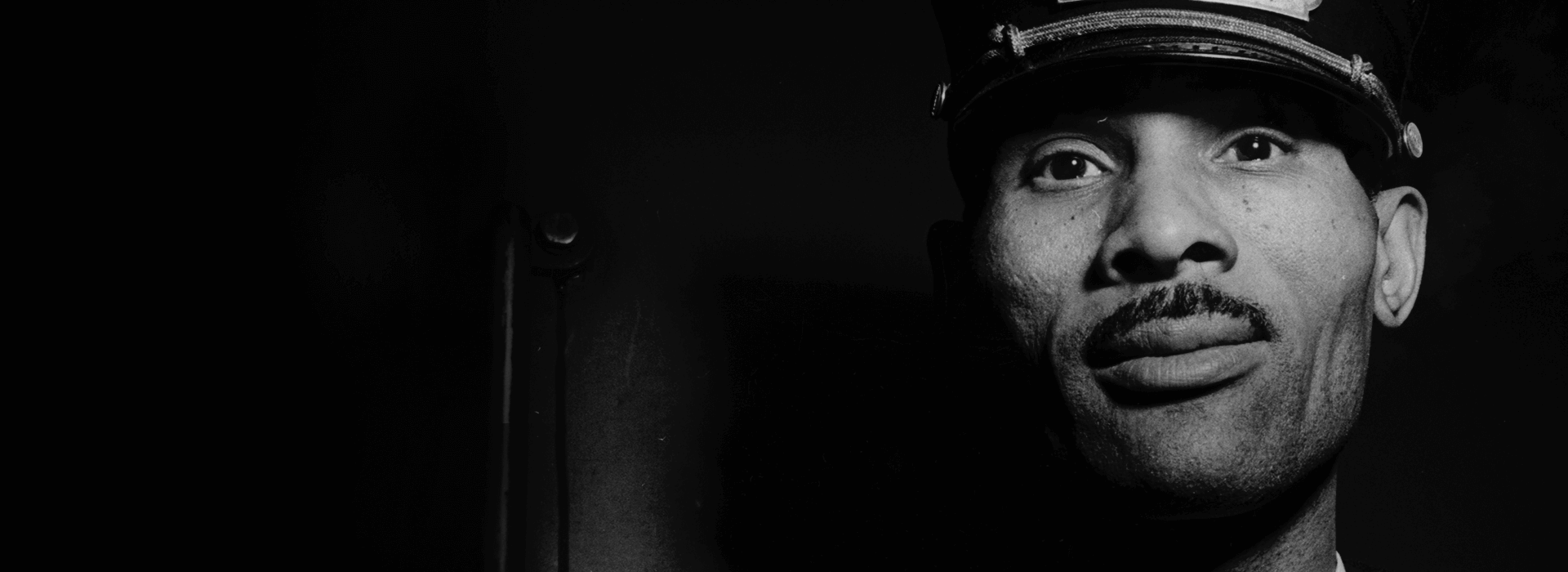

Pullman Porters

Working for the Pullman Company was, however, less glamorous in practice than it appeared. Porters depended on tips for much of their income and thus on the generosity of White passengers who often referred to all porters as “George”, the first name of George Pullman, the company’s founder. Porters spent roughly ten percent of their time in unpaid “preparatory” and “terminal” set-up and clean-up duties, paid for their food, lodging, and uniforms, which could consume up to half of their wages, and were charged whenever their passengers stole a towel or a water pitcher. Porters could ride at half fare on their days off — but not on Pullman coaches. They were not promotable to conductor, a job reserved for whites, despite frequently performing some of the conductor duties.

The porter had to do everything from greeting passengers; carrying baggage; making up sleeping berths; to cleaning the cars; cooking & serving meals; and shining shoes. They were paid very poorly, having earned $1 dollar per day, & worked 21 hours per day, 7 days a week. Because of the low pay, the porters had to depend upon tips to earn a living. These Black men had to be on call night and day to service the passengers and spent long periods of time away from their loved ones.

According to Dr. Lyn Hughes, Founder & President, The Pullman Porter Museum, it was “required to work 400 hours per month … or 11,000 miles, whichever came first … the pay was about $60 per month. From that pay, $33 went towards the expenses they incurred … they had to buy their supplies, nothing was given to them, the towels that they used, the sheets that they used …”

Porters suffered long hours of work; low pay; taxing work; diminished hours of sleep; 24 hours/day on call responsibility; excessive absences away from loved ones and Pullman’s severe code of conduct. Because these Black men worked much longer hours under more stressful conditions than their White counterparts for less than half the pay & also were excluded from certain positions, the porters attempted, in 1909, to form a union … their own union.

The economic separation, deprivation, and marginalization of the Black community forced by Jim Crow and the doctrine of advancement through self-reliance preached by Booker T. Washington led many Black leaders to look with distrust on joining with whites on issues of common concern — and often denied that Blacks and Whites had any common interests at all. Furthermore, and foremost, racial discrimination remained entrenched in most every institution that existed in the United States, and these racist beliefs and practices, both subtle and overt, empowered the White labor movement to bar, by whatever means, the Black workers and their efforts to organize. The Pullman porters were intimidated & threatened with lower wages, violence, loss of jobs and some even fired for attempting to form a union.

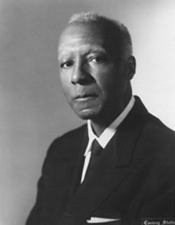

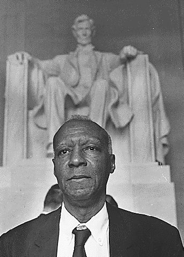

Upon discussions, three men representing the porters met with Asa Phillip Randolph. Randolph was highly supportive of the Pullman porters and their plight, covering articles on them in a magazine, “The Messenger”, of which he was a co-founder+publisher, with Chandler Owen.

Randolph, who had “failed” four times prior as an organizer, was sought because he was actively supportive but also because he was astute, highly articulate & unable to be threatened, employment-wise, by the Pullman company. Randolph accepted their request to lead them and on August 25, 1925, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was founded. Their motto was “Fight or Be Slaves”!

The forming of the BSCP was critical because by the 1920s, Blacks were employed by Pullman as porters but also as dining car waiters, lounge car attendants and onboard servers as well as firemen, maids, and railcar attendants. With over 20,000 BSCP members employed by Pullman, these Blacks comprised the largest category of Black labor!

The Brotherhood had to fight on four different fronts: the Pullman Company; supporters of the Pullman Company within the Black community; the White hegemony; and unions within the American Federation of Labor that were hostile to the Brotherhood members’ claims for employment equality. The BSCP also tried to involve the federal government in its fight with the Pullman Company: on September 7, 1927 the Brotherhood filed a case with the Interstate Commerce Commission, requesting an investigation of Pullman rates, porters’ wages, tipping practices, and other matters related to wages and working conditions; the ICC ruled that it did not have jurisdiction to decide the case of the BSCP. Randolph worked tirelessly, despite constant threats and consistent attempts to bribe him. He firmly stood his ground & was considered by many, especially President Franklin D. Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, of great integrity.

By 1933, BSCP membership dropped to 658 members, and the headquarters lost telephone and electric service because of nonpayment of bills. In 1934, the Roosevelt administration, however, amended the Railway Labor Act and then in 1935, passed the Wagner-Connery Act, which outlawed company unions and protected porters. The BSCP immediately demanded that the National Mediation Board certify it as the representative of these porters. The BSCP defeated the company union in the election held by the NMB and on June 1, 1935 was certified. Two years later, the union signed its first collective bargaining agreement with the Pullman Company.

Legacy

In 1937, the Pullman Company finally recognized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, signed a labor agreement to reduce their hours & increased the pay of these men. A. Phillip Randolph made possible the first African- American labor union in the United States and the BSCP’s defeat of the Pullman company was an incredible feat that would set the stage for the Civil Right Movement!

The BSCP had laid the foundation in fighting for & attaining civil rights in the workplace. These brave members also politically, & often financially, supported civil rights organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Of significant note, the original “March on Washington” was organized by Randolph in 1941, twenty-two years before the historic one he chaired in 1963. In 1941, Randolph used the threat of a community march on Washington and garnered support from the NAACP; New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia; and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to force the administration to ban discrimination by defense contractors and establish the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to enforce that order.

Milton Webster, the BSCP’s First Vice-President, worked to make the FEPC an effective tool in combatting employment discrimination. Utilizing solidarity in forms ranging from Black leadership to Black dollars, the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters, directly confronted racial discrimination. These confrontations occurred beyond the railway system, extending from police brutality to gross exploitation of Black farmers.

Randolph achieved his other demand — the end of racial segregation within the military — seven years later, when President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981 banning it. It was called off due to the passage of the Fair Employment Practices Act by President FDR, who actively supported Randolph and the BSCP in their quest for better pay and better benefits!

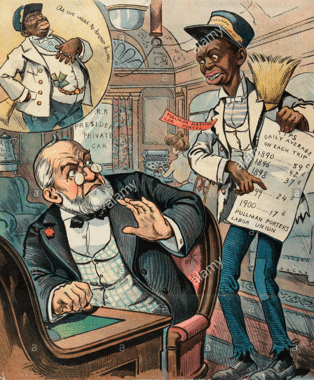

Depiction in the Media

Often the porters were portrayed in the media in negatively racial stereotypes and denigrated in music, stage & film, despite their extreme professionalism.

-

-

Al Jolson, a “Jew” who identified as “White”, in a promotion advertisement for the 1913 Pullman Porters Parade. Jolson has been popularly referenced as “The King of Blackface Performers”. -

With great sacrifice, the Pullman porters supported families, even throughout The Great Depression, many saving in such a manner that it is said that they created “The Black Middle Class”, socioeconomically, educationally & politically. Because of the economic stability of many, they provided their loved ones with opportunities for a greater quality of life, including sending their children on to higher education.

For greater than 100 years, 1858-1969, these outstanding Black men provided stellar service, working on trains traveling throughout the States, despite extreme adversity; they fought valiantly against obscene prejudice & discrimination in a racially-segregated work environment … as the nation’s first Black labor union, members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters developed the foundation for Black labor unions, the Black middle class and for the Civil Rights Movement!!