Because of her …

Ayanna Pressley, U.S. House Representative (Massachusetts)

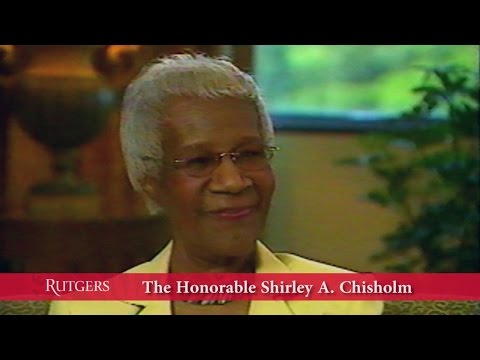

Shirley Anita Chisholm (née St. Hill) was born to Charles and Ruby St. Hill on November 30, 1924, in Brooklyn, New York. Her parents had immigrated from the Caribbean: her father, originally from British Guyana, settled in New York City by way of Cuba and her mother hailed from Barbados. She was the oldest of four daughters. Her father worked as a factory worker and an assistant in a bakery while her mother was employed as seamstress and a domestic worker. Although they worked very hard, they had very little resources. Like many Blacks suffering racial discrimination in the United States, they experienced great economic instability.

In 1929, the St. Hills, in wanting the best for their daughters, sent Shirley and her sisters to live in Barbados with their maternal grandmother, Ms. Emaline Seale. The island country, still greatly influenced by British colonialism, had a rigorous education system and Seale ensured that her granddaughters benefitted from it. Chisholm wrote in her autobiography, Unbought and Unbossed, “Years later I would know what an important gift my parents had given me by seeing to it that I had my early education in the strict, traditional, British-style schools of Barbados. If I speak and write easily now, that early education is the main reason.” Chisholm would identify as Barbadian-American because of her life and ancestry connected with both Barbados and the United States.

Shirley returned to the States at the age of ten. The St. Hills’ investment in improving their daughters’ futures, especially regarding education, proved to be profound. Shirley would graduate from the prestigious Brooklyn Girls’ High School in 1942; graduate cum laude from Brooklyn College in 1946 and graduate with her Master of Arts degree from Teachers College of Columbia University in the City of New York in 1951. Having earned both of her degrees in education, she would work in the field of early childhood education. Prior to matriculating at Columbia, she married Conrad Q. Chisholm, a private investigator of Jamaica descent, in 1949.

Her passion for platforms, including rights of Blacks, women and immigrants, motivated her involvement in various clubs and organizations at the university level. This involvement included the Pan-American Club, the Harriet Tubman Society, the Social Service Club, the Debate Team and Delta Sigma Theta, a Black sorority. While at Columbia, a professor enthusiastically encouraged her to enter politics. While they acknowledged that some, if not many, will be prejudiced against her because of her race and gender, Chisholm became actively involved in her community. She was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Urban League, the Bedford-Stuyvesant Political League and the League of Women Voters. Perhaps what would be most pivotal would be her involvement with the Democratic Party Club in Brooklyn.

She balanced her involvement with these organizations with her professional career of serving as a director of the Friends Day Nursery in Brownsville and the Hamilton-Madison Child Care Center in Manhattan (1953-59). In 1959, she was hired as an educational consultant for the Division of Day Care and worked in this position for five years. Her expertise in early education and children welfare was a natural lead for her involvement with politics.

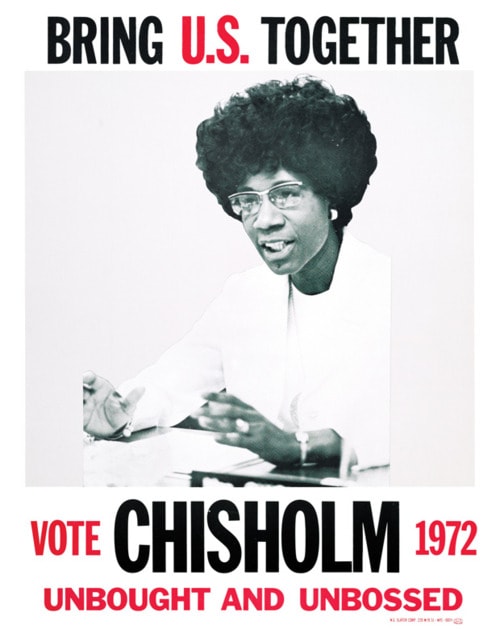

In 1964, Chisholm became the second Black to be elected to the New York State Legislature; the first to be elected to the New York State Legislature was Reverend Dr. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. As with Powell, Jr. and his district, which included the highly Black-populated Harlem, Chisholm’s Bedford-Stuyvesant community was also highly Black-populated, due to a 1968 redistricting of Brooklyn. Incumbent Edna Kelly, who was White, immediately sought re-election to represent another district. Chisholm announced her decision to run to represent the 12th District and her slogan was, “Unbought and Unbossed”. She resoundingly defeated her opponents, who included James Farmer, Jr., the former director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). In June 1968, Shirley Chisholm would become the first Black woman elected to Congress!

When Shirley Chisholm arrived in Washington, DC, she knew she would have to deal with much, especially racism and genderism. She was determined, however, to best serve those in need. She fought for rights of minorities, women and immigrants, of which she was all three.

Originally, she was assigned by House leadership of her own party to the agricultural subcommittees dealing with forestry and rural development. She asserted that the interests of the agricultural subcommittees, including farming, had nothing to do with the needs of her constituents in Bedford-Stuyvesant; she felt insulted and ignored. In Rebbe: The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson, the Most Influential Rabbi in Modern History, author Joseph Telushkin wrote that when Chisholm shared her concerns with Rabbi Menachem Schneerson, he advised her to utilize the resources of the agricultural subcommittees to meet, via milk and fresh foods, the needs of those in her district and beyond. Chisholm would also be instrumental in significantly expanding the outreach of the federally-funded Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Woman, Infants and Children (WIC).

Shirley Chisholm would make history again as she became the first freshman member of Congress to have her committee assignment changed by House leadership to the Veterans’ Affairs Committee. As a Congresswoman, Shirley Chisholm would serve on three committees: The House Agriculture Committee, the Veterans’ Affairs Committee and the Education and Labor Committee, of which Powell, Jr. had successfully been the Chair. She introduced greater than 50 pieces of legislation, including the increase of federal funding for childcare and extension of the right of minimum wage to domestic workers. She demanded the end of American involvement in the Vietnam War and advocated for economic equity as well as racial and gender equality. Shirley Chisholm hired only women as her staff members and ensured that half of them were Black. She saw these specific actions as essential to positive political change for this country. She often said that she experienced more animosity for being a woman in politics than being a Black person in politics. To further promote the positive political change she sought, in 1971, Chisholm co-founded the Congressional Black Caucus and the National Women’s Political Caucus. She also decided to campaign to become President of the United States.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In January 1972, Shirley Chisholm became the first Black candidate for a major party’s nomination for President of the United States. Concurrently, she was the first woman to run for the presidential nomination of a national party, The Democratic Party. In her announcement of candidacy, she said her representation of “The People” was inclusive and she was “… not the candidate of Black America, although I am Black and proud. I am not the candidate of the women’s movement of this country, although I am a woman and equally proud of that. I am the candidate of the people and my presence before you symbolize a new era in American political history.”

Many factors, including sabotage, underfunding and lack of security negatively impacted her presential bid. She was, according to the National Women’s History Museum, “… blocked from participating in televised primary debates, and after taking legal action, was permitted to make just one speech.” Her campaign raised just $300, 000, a severely low total. While campaigning during the primaries, Chisholm, the recipient of numerous threats, survived several assassination attempts. Her husband, Conrad, would be her personal security until the U.S. Secret Service, finally, in May 1972 provided her protection. Sadly, Chisholm had very little support from Black congressmen, even those members in the Congressional Black Caucus, which she co-founded.

Adding to these factors was Chisholm’s visit to Governor George Wallace (AL) after his being shot five times. Arthur Bremer had attempted to assassinate Wallace in Maryland while Wallace was campaigning against segregation. Despite their differences in ideologies, she said she visited Wallace because it was the humane thing to do. However, to her supporters, her decision to see Wallace brought suspicion and doubt about her sincerity and interests. He, at the time, was one of the most avowed, racist politicians in the United States. It should be noted that, after the shooting, “the most dangerous racist in America”, as Wallace had been referred, renounced many of his racist views and actions. He supported Chisholm and was integral in assisting Chisholm in getting legislation passed by his Southern colleagues in Congress.

Although she would not win the Democratic Party nomination, she got her name on the primary ballots of 12 states, won 28 delegates in the primary elections and attained 152 of the delegates votes (10% of the total). When asked about her experience, Chisholm said, “I ran because I felt that the time had come, that a Black person or a female could be, should be President of the United States … not only White males. I decided that somebody had to get it started.” In her concession speech, she stated, “I did not expect to win; I understand because I am not White, I am not male, that I am not going to get the blessings of the power structure of this country.”

Chisholm continued to serve in Congress, including being elected to serve as Secretary of the House Democratic Caucus, and continued to support education and social services. She and Conrad divorced in 1977 and that same year, she married Arthur Hardwick, Jr., a Black politician who had previously served as an Assemblyman for New York. They knew each other when they both served on the New York State Assembly. Later, her husband’s injuries that had been sustained from an automobile accident and the Democratic Party’s liberal responses to the ultra-conservative policies of President Ronald Reagan would significantly influence her decision to leave the professional, political arena.

Shirley Chisholm retired after serving 7 terms (1969-1983) in Congress. In her retirement, she continued to be active, advocating for advancement of Blacks, women, children, immigrants and those often underserved. She held the position of Purington Chair, teaching political science and sociology, at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, and taught as a guest lecturer at Spelman College in Georgia. The former is an all-female university and the latter is an all-female, historical Black university. She continued to encourage activism on all levels, but especially on the local level, and even co-founded the organization, African-American Women for Reproductive Freedom.

In 1991, she retired to Florida, and, suffering declining health, she was unable to accept the 1993 nomination of President Bill Clinton to be the U.S. Ambassador for Jamaica. That same year, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. In 2005, upon suffering several strokes, Chisholm passed away at the age of 80 years old.

The legacy of Shirly Chisholm is extensive. It is more than being recognized as one of the Top 10 Most Influential Women in the World. It’s more than the Peabody Award-winning documentary, Shirley Chisholm ’72: Unbought and Unbossed by the uber-talented, African-American independent filmmaker, Shola Lynch. It’s more than the 2020 nine-part series, “Mrs. America”, of FX that will star the Emmy Award-winning Uzo Aduba or the Amazon Studios film, The Fighting Shirley Chisholm, that will star the Emmy, Oscar and Tony Award-winning Viola Davis. It’s more than statues created in her honor. The most recent is the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs commission of an artist’s creation of a Shirley Chisholm statue that will be installed at the Parkside entrance of Prospect Park in her former congressional district, Brooklyn.

(No copyright infringement intended).

It is more than her being recognized by the U.S. Postal Serviced with a Black Heritage Stamp in her honor. It’s more than Congress, which broke long-standing customs by commissioning African-American artist extraordinaire Kadir Nelson to create an official portrait of Chisholm. This congressional honor of a portrait is traditionally reserved for party leadership.

Her legacy is even greater than receiving, posthumously, the Medal of Freedom by President Barack H. Obama.

In fact, her work laid the foundation for Barack H. Obama to become president and for Jesse Jackson and Hillary Rodham Clinton to run for this national executive position under the Democratic Party.

Her incredible legacy, from a political vantage, was perhaps best experienced in 2018 when the election of women to legislative, executive and judicial positions was at an all-time high. It became, as television host and political analyst Rachel Maddow would exclaim, “… the most diverse freshman class in history … with Democrats picking up 40 new seats, sending DC the most diverse and female Congress ever!”

The immense influence of Chisholm was not absent from these freshmen, or rather, freshwomen, of Congress. There are photos of these new congresswomen, including Representative Ayanna Pressley (MA), Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (NY) and Representative Rashida Tlaib (MI) taking pictures with the Nelson portrait of Chisholm and they have disseminated these pictures throughout social media.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In fact, Pressley, through the grace of Congresswoman Katie Hill (CA), resides in the office of Shirley Chisholm. Hill, also a Democrat, had drawn the better lottery number and selected the office but offered it to Pressley because of the personal and historic significance it held especially for Pressley. In the Huffington Post, Hill stated, “Shirley Chisholm was always so clear that women supporting women would move politics forward … that is more true than ever before.”

Shirley Anita Hill-Chisholm was brilliant, articulate, logical, brave and compassionate. Known as “Fighting Shirley Chisholm”, her demeanor was of determination and she was known to advise, “If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.”

Service is the rent we pay for the privilege of living on this earth.

Shirley Chisholm