“She was great in her own right …”

David Whitlow, Director, The Mooresville Museum

Born on December 31, 1900, in Mooresville, North Carolina, Selma Hortense Burke was the seventh of ten children born to Reverend Neil and Mary Elizabeth Burke. Her mother stayed at home to rear their family. Her father, who was a minister, often worked on the railroad as well as a chef aboard ships that traveled to the Caribbean, Europe, South American and, significantly, Africa.

While her father acquired artifacts from his international travels, it was those pieces from Africa, coupled with carvings and art curated from his brothers during their missionary work in Africa, that decorated the Burke home. When her uncles passed in 1913, her father inherited their collections and African arts would greatly inform and inspire Selma.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Selma, fascinated with the artwork and ritual objects of Africa and other sculptural pieces, was talented in creating sculptures. She often shaped figures from the white clay that could be found in the riverbeds near her home and from the dirt on her parents’ farm. In African American Art and Artists, Samella Lewis recorded that Selma stated, “It was there in 1907 that I discovered me.” Burke further expounded on her sentiment when she said in Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia, “I shaped my destiny early with the clay of North Carolina rivers … I loved to make the whitewash for my mother and was excited at the imprints of the clay and the malleability of the material.”

Her parents and her maternal grandmother, a painter, were supportive of her passion. However, being realists, they encouraged her to further her education and gain a skill that would allow her to support herself, especially because she was a Black girl. Selma, always bright and curious, attended a one-room, segregated schoolhouse. Due to her father’s occupation as an itinerant minister, her family moved to Washington D.C. Burke would attend the Nannie Burroughs School for Girls but her matriculation was only until she was fourteen years old, as the school did not fully support the arts. Upon leaving school, she selected nursing as her choice of profession. To attain that objective, she attended Slater Industrial and State Normal School (now known as the historically Black university, Winston-Salem State University) and graduated from St. Agnes School of Nursing at St. Augustine College in 1924. Burke moved to Philadelphia the next year and enrolled at Women’s Medical College to learn operating room techniques. In 1928, Burke married mortician, Durant Woodward, her friend from childhood; however, he would pass away from blood poisoning less than a year later.

Seeking a change and acting upon the recommendation of the College’s president, Burke moved to Cooperstown, New York in order to work as a private nurse for the heiress of the Otis Elevator Company. Her new employer paid her well and encouraged Burke to become heavily involved within the arts. Upon the heiress’ death, Burke moved to New York City and immersed herself in its culturally-rich environment.

In New York, the Harlem Renaissance, the explosion of cultural development by Black artists, activists and writers, was in full swing and Selma Burke would soon be thrust into it, forever changing her life! She was greatly inspired by many of these talents, including poet Langston Hughes; entertainer and actress, Ethel Waters; writers and composers of “Lift Every Voice and Sing”, brother Rosamond and James Weldon Johnson; and Jamaican author, Claude McKay, to whom Burke would marry and divorce twice. Their relationship, as husband and wife, was brief, and often rocky. In Claude McKay, Rebel Sojourner in the Harlem Renaissance: A Biography, Wayne F. Cooper wrote of their relationship and her ending it, as McKay would cruelly critique her pieces, even destroying those he felt were of inferior quality. Despite the failing of the marital relationship, their connection remained. McKay had introduced her to persons who would be significant influences on her life, including sculptor extraordinaire Augusta Savage. Under the guidance of Savage, Burke began teaching arts to the youth at the Harlem Community Arts Center and was active in the Harlem Artists Guild.

(No copyright infringement intended).

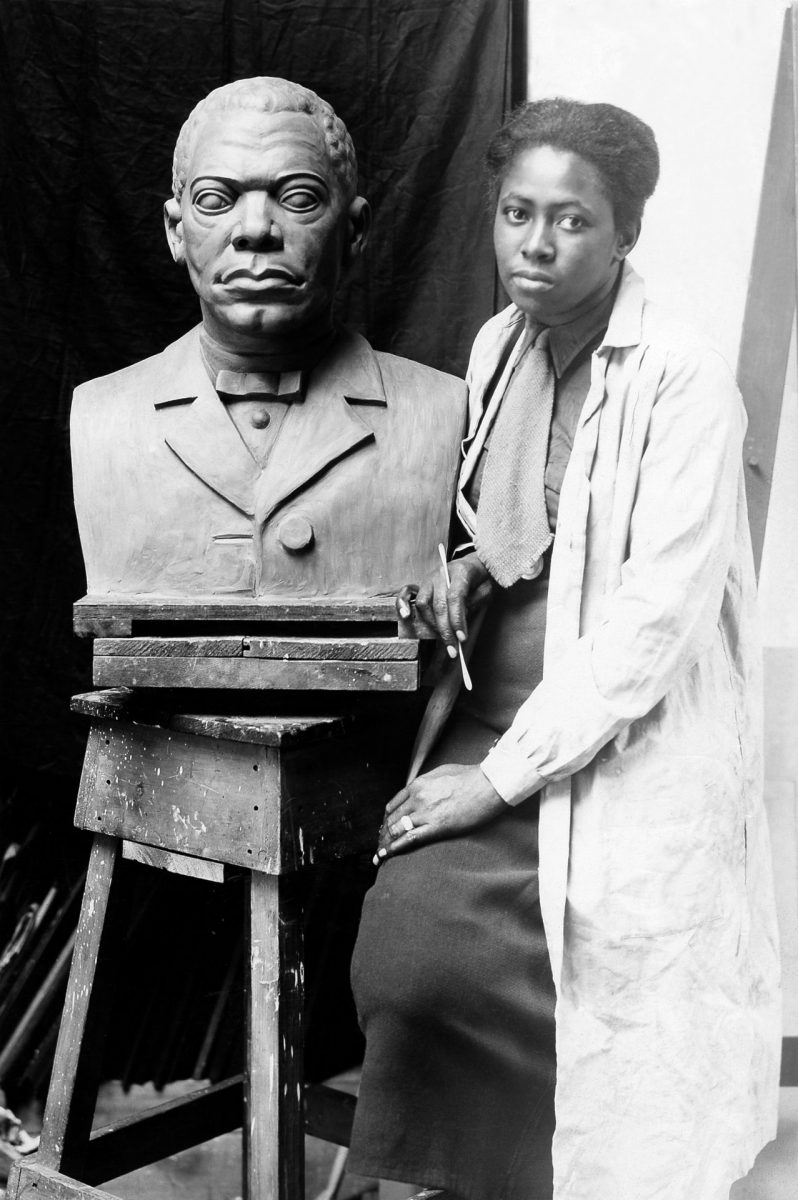

At this time, Burke became more committed to her craft. She modeled for artists at Sarah Lawrence College. She created sculptures from materials such as brass, wood, marble and stone and her subjects ranged from persons, popularly known as well as pedestrian, and nudes. The subjects of her works were presented as dignified and represented the human spirit. She sculpted pieces for the Works Project Administration (WPA) of the Federal Art project, part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s, “New Deal” program. Her most famous piece completed while at the WPA is a bust of Booker T. Washington, an author whose works included the classic, Up from Slavery. Washington also served as advisor to several presidents of the United States; co-founder of the National Negro Business League; and president of Tuskegee University. The bust was gifted to Frederick Douglass High School of the Manhattan borough in 1936.

Selma Burke began to apply for fellowships and was the recipient of 2 awards to study in Europe. The first that Burke won was the Julian Rosenwald Award (1935) from the Rosenwald Foundation, which she used to study ceramics with Michael Powolny in Vienna. The second was from the Boehler Foundation (1936), which she applied to study sculpture in Austria, France and Germany. While in Paris, she studied with Aristide Mailol and Henri Matisse and while she relished her experience there, she chose to depart early due to the rise of Nazi terrorism and returned to New York City.

Committed to teaching others, in 1940, Burke opened her own school, the Selma Burke School of Sculpture, in New York City. Also, at this time, she enrolled in graduate school at Columbia University in the City of New York; she earned her Master of Fine Arts degree in 1941. That same year, Burke mounted her first exhibit, featuring classical compositions, at the McMillen Galleries in New York City.

When the United States entered World War II, Burke joined the United States Department of the Navy and worked as a truck driver at the Brooklyn Naval Yard. When she injured her back in 1943, she had to be hospitalized and during that time, she learned about a national competition of the Federal Arts Commission to create a profile of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. She entered the competition and her design was the ultimate selection. Because Burke could not secure images of Roosevelt that she felt were appropriate in allowing her to create her best work, she wrote to the White House, seeking permission for a sitting to draw him in person. To her great surprise, she was granted permission. On February 22, 1944, Burke, accompanied with her brown butcher’s paper and charcoal, met with President Roosevelt.

The completed piece by Selma Burke was a 3’.5” x 2’.5” bronze plaque featuring the side profile of President Roosevelt. On it, above the head of President Roosevelt, was engraved “The Four Freedoms”: freedom from fear, freedom of speech, freedom from want, and freedom of worship. As a stipulation of competition, the final art piece had to be approved by members of the Fine Arts Commission and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. In a July 1945 account to The New York Times, Burke vividly recalled the criticism, particularly that the President looked too young, by the First Lady. To the critique, Burke elegantly replied, “I have not done it for today, but for tomorrow and tomorrow. Five hundred years from now America and all the world will want to look on our president, not as he was the last few months before he died, but as we saw him for most of the time he was with us—strong, so full of life, and with that wonderful look of going forward.” President Roosevelt would pass on April 12, 1945.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Six months after the passing of President Roosevelt, on September 24, 1945, Burke’s portrait was unveiled by President Harry S. Truman for its first viewing to the public. It was installed at the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C., where it presently hangs. To honor his extensive legacy and his founding of the March of Dimes to combat polio, Congress and the U.S. Mint elected to change the appearance of the coin, placing the profile of the late president on it. At that time, the profile of the goddess, Liberty, wearing a winged cape, had been engraved on its front. Nellie Tayloe Ross, Director of the U.S. Mint, selected John R. Sinnock, chief engraver for the U.S. Mint, to create the image of President Roosevelt.

Selma Burke’s claims that her image was stolen by Sinnock, who is credited with creating the image of President Roosevelt on the dime, is controversial. Scholars, historians, Mint officials and numismatists cannot agree about the validity of Burke’s claims, especially when the National Archives in Washington D.C., the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Records Administration of the President Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, New York, stated that the origins for the portrait of the dime is from Burke. In an Atlas Obscura article, “Who Really Designed the American Dime” by Christina Ayele Djossa, she wrote of Burke’s accusation against Sinnock and moreso, against the US government. Burke felt she had been undermined and overlooked because of her race, gender, political affiliations and the change in political administration after President Roosevelt’s death. Adding support to Burke’s claims is Edward Rochette, a former American Numismatic Association president, who, according to Djossa, “ … went a step further, suggesting that the reverse of the dime was also inspired by the Four Freedoms sculpted into Burke’s plaque …”

However, there are obvious differences between the sculptor’s image and the engraver’s image. Until his passing in 1947, which was a year after the newly-designed coin was issued, Sinnock denied Burke’s accusations. Additionally, both had sitting sessions with President Roosevelt. To his credit, Sinnock, whose initials are on the dime, had created previous designs of the president that dated back to 1933. These designs include the image of President Roosevelt on his third inauguration medal (1941), which looks identical, barring profile direction, to the image he created for the ten-cent piece. For the rest of her life, Burke held strong to her belief that she had been stolen from and discredited. In a 1994 interview with journalist Steven Litt, highlighted in the post, “The Selma Burke Controversy Lives on Long After the 1940s” of Numismatic Guaranty Corporation, Burke decried, “I am so mad at that man … this has happened to so many Black people … I have never stopped fighting this man and have never had anyone who cared enough to give me the credit … everybody knows I did it.”

Continuing to grow in her passion, in 1946, Burke started another school, the Selma Burke Art School, this too, situated in New York City. She taught in diverse environments, including Swarthmore College, the A.W. Mellon Foundation and Harvard University. Her work at the Harlem Art Center influenced many African-American artists, including Ernest Crichlow and Jacob Lawrence. In 1949, she married again, to architect Herman Kobbe, and they moved to live in an artists’ colony in New Hope, Pennsylvania. Kobbe passed away in 1955 and Burke remained living in Pennsylvania until her passing. In Pennsylvania, she continued being active as an artist and educator. Determined to be an asset to her community, she created a source for the arts, especially Black arts, and opened the Selma Burke Art Center in Pittsburgh, which operated from 1968-1982. Aside from being an arts administrator, Burke also taught for 17 years in the Pittsburgh Public Schools system. Burke became active with the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, appointed by, and serving under, three different governors, including former Governor Milton Schapp, who proclaimed June 20, 1975, to be “Selma Burke Day” in Pittsburgh in recognition of her contribution to the arts in Pennsylvania.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Selma Burke was commissioned to create over 20 sculptures in bronze and wood and her most notable pieces include busts of Mary McLeod Bethune, an educator, “national advisor” to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, founder of Bethune-Cookman College and president of the National Association of Colored Women; and of A. Phillip Randolph, activist and president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first African-American labor union in the United States. Burke was also known for her sculptures Temptation (1938), Sadness (1951), Fallen Angel (1958), Untitled, also known as Woman and Child (1968) and Together (1975). In her 80s, she completed her final monumental piece, a nine-foot statue of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., which was installed in 1980 at Marshall Park in Charlotte, North Carolina.

The works of Selma Burke are held in private and public collections, including in the Hill House Center in Pittsburgh; Winston-Salem State University in North Carolina; the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in the Harlem community in New York City; the National Archives as well as the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C. Her works are also in the collections held at the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The recipient of numerous awards and accolades, including the Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women as well as the Pearl S. Buck Foundation Women’s Award, Burke was a member of the inaugural group of recipients to be awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Women’s Caucus for Art. Burke, an honorary member of Delta Sigma Theta sorority, bequeathed her papers and other archival material to Spelman College. This act illustrated her strong support for Black women becoming educated, as Spelman is a historically Black liberal college for women. A fervent believer in continuing her education, Burke, a recipient of 8 honorary degrees, earned her Doctorate of Arts and Letters from Livingston College at the age of 70 years old! The value of education never left her mother either, as Mary entered Winston-Salem State University at the age of 75!

On August 29, 1995, Burke, ill with cancer, passed away in New Hope, Pennsylvania. Her work, as an artist, learner, educator and administrator, has had an enormous impact and when asked about her motivation, she stated, “I want to show that art … is not money … it’s a life.”

“I really live and move in the atmosphere I am creating …”

Selma Burke