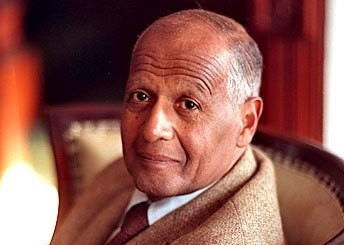

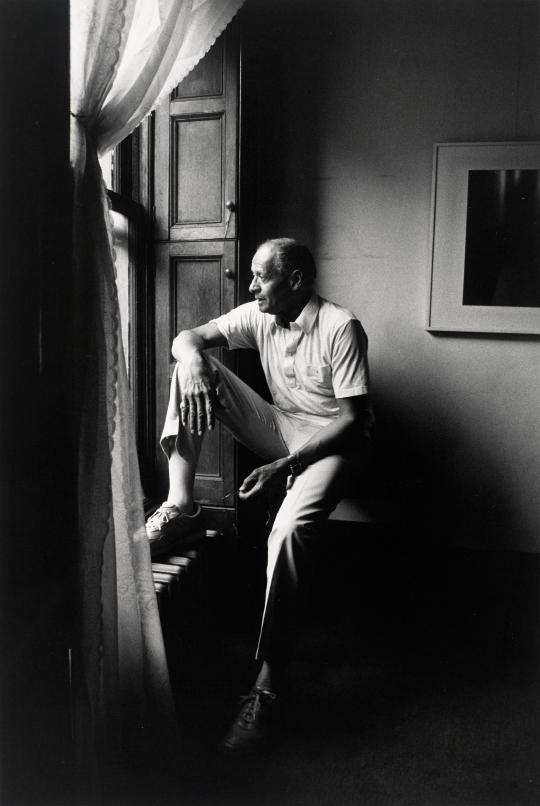

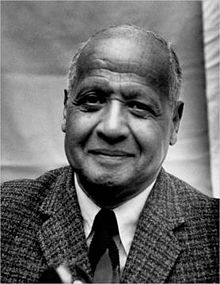

“Roy DeCarava is a giant of American art photography. His practice, spanning six decades of American history, recorded aspects of African American life and culture over decades of drastic change … His photographs are less a record and more a collection of poetically composed glimpses of genuine human experiences.”

~ Ocula

On December 9, 1919, a baby boy was born at Harlem Hospital to Elfreda Ferguson; she named him Roy Rudolph and his last name was DeCarava. Newly arrived to New York from her home country of Jamaica, she was only seventeen years old. Alone, she reared Roy, who never knew his father. Elfreda worked very hard to support herself and her son, even taking on other opportunities to pay for his music lessons and interest in art. From the early age of five years old, he knew he wanted to be an artist. An activity in which his mother often engaged was photographing her friends and neighbors in the Harlem community. This would be an incredible influence on his life, most notably, his love for Black people in the famous neighborhood of the Manhattan borough in New York City.

Roy DeCarava came of age during the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural explosion created and curated by Black artists, authors, educators, entertainers and writers. Dedicated to his art interests, he attend the annex of the 18th Street Textile High School that was located uptown near his home. He later transferred to its main campus midtown, where he was only one of two Black students in the revered school.

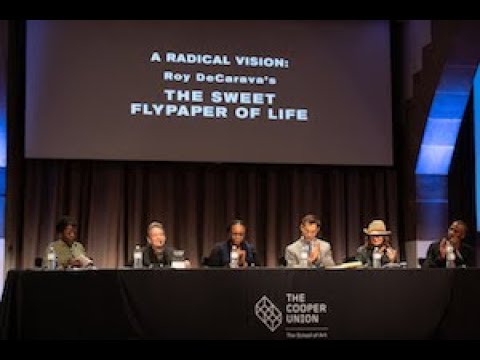

After graduating in 1938, he worked briefly in the poster division of the Works Progress Administration while attending the School of Art at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. However, facing racial prejudice and discrimination, DeCarava left The Cooper Union and transferred to the Harlem Community Arts Center. He attended this center, which was sponsored by the WPA, from 1940 until 1942. He was able to connect and build with brilliant and talented Blacks including premier artists Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence; writer and celebrated poet of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes; and accomplished actor, activist, athlete and singer Paul Robeson.

He married but in 1942, DeCarava was drafted into the U.S. Army. Stationed in Virginia and then Louisiana, it was the first time that he had experienced such virulent racism and violent discrimination of the Jim Crow South. Suffering a mental breakdown, he was institutionalized. The artist reflected on this trauma in the brief biography written by Peter Galassi for an exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). In it, Roy DeCarava shared, “The only place that wasn’t segregated in the army was the psychiatric ward of the hospital. I was there for about a month. I was in the army for about six or seven months altogether, but I had nightmares about it for twenty years.”

Given a medical discharge, DeCarava returned to Harlem and art. Enrolled at the George Washington Carver Art School from 1944 until 1945, he studied drawing and painting with African-American artists including the legendary Charles White. He soon began working in printmaking, which became a new passion of his. At this time, he bought his first camera and used it as a means to record material for his prints. However, as the 1940s drew to an end, he abandoned printmaking and painting to exclusively work in photography.

Roy DeCarava used a handheld 35mm camera for his work, allowing him to be mobile and accessible to connect with his subject(s). Commenting on the artist’s unique methods and insight, David Zwirner offered, “Unlike most photographers of his day, DeCarava developed and printed his own images himself, enabling him to create over time a distinct and enduring aesthetic approach. He was successful in his imagery from the beginning and his work has widely influenced that of contemporary artists today. He recognized early on that the process of making a photograph begins long before one even picks up the camera and is not complete until the image has been printed to its inner calling.”

In 1950, the artist held his first solo exhibition at Forty-Fourth Street Gallery in New York City. His work greatly impressed Edward Steichen, who was the director of the newly-established Department of Photography at MoMA. Steichen purchased three images and he soon became an advocate for DeCarava’s work. A part of this advocacy was his support of the photographer to apply for fellowships and other opportunities to continue and expand upon his vision. In 1952, Roy DeCarava became the first African American photographer to win a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.

(No copyright infringement intended).

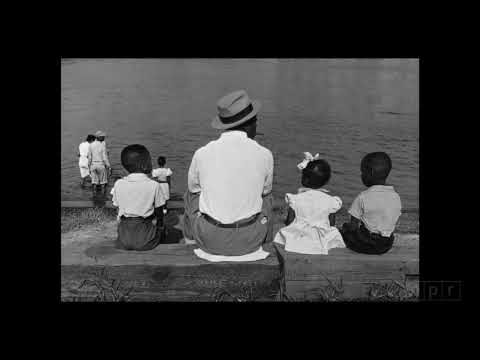

In his application essay, DeCarava clearly stated his purpose. In “Roy DeCarava, Obituary” by Robert Williams and published in The Guardian, he quoted the photographer’s sincere intent. DeCarava wanted to capture on film Harlemites “morning, noon, night, at work, going to work, coming home from work, at play, in the streets, talking, kidding, laughing, in the home, in the playgrounds, in the schools, bars, stores, libraries, beauty parlors, churches, etc., … I do not want a documentary or sociological statement; I want a creative expression …”

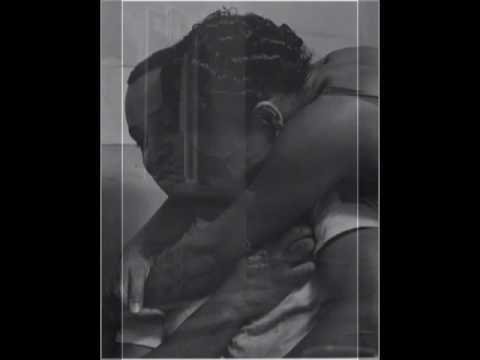

The prestigious, one-year grant permitted Roy DeCarava to focus solely on photography and he spent his time taking hundreds of photographs throughout Harlem. His breathtaking talents and skills were shared by DeCarava’s second wife and widow Sherry Turner DeCarava for “In Sublime Photographs, Harlem’s Past Remembered” written by Thomas Gebremedhin for the Wall Street Journal. She proclaimed, “Roy was fascinated by photographing couples. He felt that there was a magnetism between men and women that went unaddressed by photographers who were more interested in superficial aspects of relationships rather than the things people expressed in gestures, words and through interaction. He photographed the invisible. I was interested in music and had been taking piano lessons. I wasn’t a prodigy or anything. I don’t remember him taking the picture for Sherry Singing. All I remember is seeing it as a finished image and him titling it. I didn’t even realize I was singing. I thought I was just practicing [piano]. We often think of artists and artwork as expressing the deepest emotions of the artist, but Roy’s work expresses the deepest emotions of the subject and the artist. It’s kind of the ultimate couple. That’s part of his work, the kind of mystery of finding the subject and finding the thing that can’t be expressed openly.”

In the summer of 1954, thirty four year-old DeCarava shared his images with the prolific African-American writer and activist Langston Hughes. Ecstatic over the photographs, Hughes reached out to his colleagues at Simon and Shuster publishing house. Of the many images the photographer took, one hundred and forty-one were selected by Langston Hughes to form their moving, photography-poetry collaboration, The Sweet Flypaper of Life, released in 1955.

Hughes’ narrative is presented from the vantage of a fictional character, Sister Mary Bradley who resided at 113 W. 134th Street. The book reflects the diverse aspects of Black life in Harlem. Groundbreaking in its impact, the photographic visual literature was reprinted several times due to being in such great demand. In discussing The Sweet Flypaper of Life, an administrator at Africanah.org wrote, “DeCarava’s photographs echo the social dimensions of the textual narrative. Combined, text and image create a powerful and complex commentary on issues of pride, family, racism and the daily struggle that is life.”

Also of significance in 1955 was the feature of several of his photographs in The Family of Man exhibition at MoMA and his founding of A Photographer’s Gallery. The Steichen-curated exhibit toured globally for a decade, drastically increasing the influence and popularity of Roy DeCarava. His New York City gallery was located in his apartment at 48 W. 84th Street on the Upper West Side in Manhattan. Focusing exclusively on American fine art silver gelatin photography, it was the only gallery of its kind in the United States. Additionally, A Photographer’s Gallery, according to The Guardian article, was “only the second of its type in the city, exhibiting the work of Harry Callahan, Berenice Abbott, Jay Maisel and others.” He presented both his own work as well as mounted twelve exhibitions.

In 1956, he began photographing American musicians and his distinctive work in black and white, silver gelatin photographs. Often capturing them while performing, his subjects included Louis Armstrong, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington and Billie Holiday. His work has also been featured on album covers of musical artists, including Davis, blues guitarist Big Bill Broonzy and gospel great, Mahalia Jackson. Many of DeCarava’s images, compiled in 1962, would comprise the book, The Sound I Saw: Improvisation on a Jazz Theme, published in 2001. When DeCarava chose the images for this book, he said, according to The Guardian article, they were “photographs of wives and children, of a packed suitcase lying open on a bed, of washing hung across a tenement alley, of everyday street scenes, interleaved with images of the musicians. Instead of creating the standard iconography, he examined the layers and textures of the lives that he had witnessed while growing up in Harlem, New York.”

In this book, he provided his own commentary. In the aforementioned essay, he commented on his utilization of darkness and light. Referencing this use, a 1987 interview with Val Wilmer, he wisely stated that, “The difference between me and other photographers is that I refuse to accept darkness as a limitation.” Williams proffered that while there “may have been sadness and struggle in his photographs, but there was also warmth, nobility, laughter and physicality, the latter particularly evident in his striking images of dancers.”

Roy DeCarava closed his gallery two years later and in 1958, he became a full-time, freelance photographer. His work was featured in publications such as Fortune, Good Housekeeping, Newsweek and Sports Illustrated.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1963, DeCarava co-founded and served as the first director of the Kamoinge Workshop. “Kamoinge” is Kikuyu for “collective effort. Based in Harlem, this art collective supported the work of Black photographers, including Beuford Smith. It presented public programs, exhibited showings, provided critical commentary on works and published portfolios.

During the late ‘60s, Roy DeCarava, who was divorced at this time, met African-American art historian Sherry Turner, who worked at the Brooklyn Museum. Building upon their professional and personal interests, the two married in 1971. They would have three daughters.

In 1969, he began teaching photography at The School of Art at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. Also that year, the famous Harlem on My Mind mounted at The Metropolitan Museum of Art premiered. DeCarava publicly refused to participate in the exhibit because it was developed by White curators who he believed had little respect, understanding, appreciation or love for Harlem, Black people and history.

He left teaching at The Cooper Union after three years but continued to teach photography at institutions of higher learning in New York City. In 1975, he joined the faculty at Hunter College and he later taught at City University, where in 1988, he was named “Distinguished Professor of Art”.

Roy DeCarava continued to create and inspire over the next two decades. His exhibitions have been shown at a number of esteemed institutions including MoMA, the Studio Museum of Harlem and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City; and the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. His work is held in numerous, prestigious permanent public collections including the Art Institute of Chicago; Andover Art Gallery at Andover-Phillips Academy in Massachusetts; Atlanta University; Detroit Institute of Art; Harvard Art Museums in Massachusetts; Philadelphia Museum of Art; and Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University in California.

On October 27, 2009, Roy DeCarava passed away at his family home in Brooklyn; he was eighty-nine years old.

For his contributions to American art, DeCarava was gifted honorary degrees from the Art Institute of Boston; the Maryland Institute of Art; the New School for Social Research; the Parsons School of Design; Rhode Island School of Design and Wesleyan University.

(No copyright infringement intended).

The recipient of accolades and honors, his work garnered him the Benin Creative Photography Award in 1972; a Master of Photography Award from the International Center of Photography in 1998; and Gold Medal for Lifetime Achievement by The National Arts Club in 2001. In 2006, Roy DeCarava was awarded the National Medal of Arts from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) by President George H. Bush. It is the highest civilian honor given by the NEA and is presented by the President of the United States.

“Look at me and see my work. Look at my work and see me.”

~ Roy DeCarava