“His pioneering career has encouraged others to cross a chasm of historic biases.”

William J. Bates, President, American Institute of Architects

On February 18, 1894, Paul Revere Williams was born to Chester and Lila Williams. The family had recently relocated from Memphis to Los Angeles. By the time that Paul had turned 2 years old, Chester had suffered and passed away from tuberculosis; Lila, battling the same illness, would pass away two years later. At the age of 4 years old, Paul and his older brother, Chester, Jr. would be sent to live in different foster homes.

Paul was sent to the home of C.D. and Emily Clarkson, who were highly supportive, educationally and, later, artistically, of him. He was the only African-American in his elementary school, but was exposed to a culturally ethnic population when he matriculated Polytechnic High School. His love of art and drawing prompted a Clarkson family friend, who was involved in construction, to suggest that Williams also study geometry and physics in order to become involved in architecture. Others, however, including a guidance counselor at his high school, discouraged him from that profession simply based upon his race.

Fortunately, Williams did not let that and similar encounters with racial prejudice and discrimination undermine his goals to become an outstanding and prolific architect he would become. In his essay, “I Am a Negro”, published by American Magazine (1937), Williams wrote, “If I allow the fact that I am a Negro to checkmate my will to do, now, I will inevitably form the habit of being defeated.” Upon graduation from Polytechnic in 1912, Williams began studying at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design and then at the Los Angeles site of the New York-based, Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, under the auspices of the local atelier. He then entered the University of Southern California to study architectural engineering. While studying, he also sought apprenticeships in local architectural firms. During this time, he won a student competition for his design for the new civic center in Pasadena; the award of $200 (USD) would mark the first time he would receive compensation for one of his designs!

In 1915, Williams became certified as a building contractor. In 1917, Paul R. Williams married Della Mae Givens and they had three children: Paul Revere, Jr., Marilyn Frances, and Norma Lucille. His son passed on his first day of life and the loss of Paul, Jr. would always be felt by Paul and Della Mae.

In 1920, attempting to gain more positive exposure, he served on the first Los Angeles City Planning Commission. In 1921, he was licensed as an architect by the State of California, making Paul R. Williams the first licensed African-American architect west of the Mississippi River! Prior to becoming licensed, he was sought by a former classmate at Polytechnic to design a home. This project, valued at greater than $90,000 (USD) at the time, was his first lucrative contract!

However, racism forever loomed … the home was in the segregated Flintridge Hills of Los Angeles and this community had segregation covenants that not only barred non-Whites from purchasing homes there but those non-Whites, especially Blacks, could not even spend the night in a home. The derogatory social rules and legal codes of concerning business in Flintridge Hills would be one of many more barriers to come. The propagated, fallacious propaganda of White superiority and Black inferiority was constantly disproven by the outstanding achievements of many African-Americans; Williams was stellar proof. Williams, a Black man, would design and oversee the development of what would be the greatest structures that defined the golden era of Los Angeles!

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1922, he established his own practice, Paul Williams and Associates, and in 1923, Williams became the first African-American to become a member of the Southern California chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). The economic boom of the early ‘20s prompted growth throughout the United States, and Los Angeles was greatly impacted. This growth allowed Williams to design small, affordable homes for the working class and extended to more grand styles for the wealthy in exclusive neighborhoods including the aforementioned Flintridge Hills, Hancock Park and Windsor Square.

In 1924, he, with Norman F. Marsh, co-designed the 2nd Baptist Church, one of the two oldest African-American churches in Los Angeles. The following year, he designed the 28th Street YMCA, which not only sought to meet the needs of Black youth in Los Angeles but served as a pivotal meeting place for African-American leaders in that community. In 1929, President Calvin Coolidge appointed Williams to the National Memorial Commission, on which he served for three years. In 1933, he was appointed to serve both on the first Los Angeles Municipal Housing Commission and on the National Board of Municipal Housing.

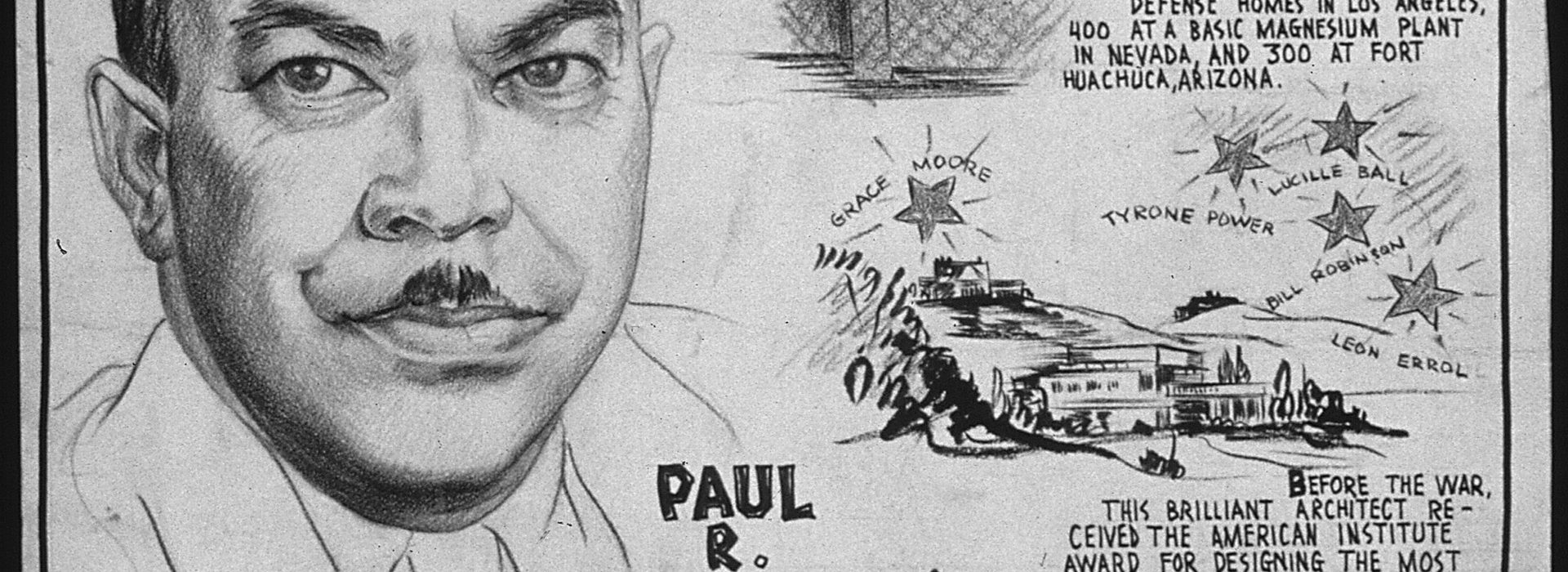

Being close to Hollywood presented Williams the opportunity to design structures, such as the Atkins House in Pasadena, for sets utilized in television show and film productions. By the late 1930s, he had won 2 significant nonresident commissions: one for the Music Corporation of America (MCA) Building and the other for Saks Fifth Avenue, both to be located in the elite, cosmopolitan area of Beverly Hills. In 1939, he won AIA’s “Award of Merit” for his design of the MCA Building, which later served, until 2018, as the international headquarters for the award-winning, Paradigm Talent Agency. His work was showcased in exhibits and enhanced advertisements.

Despite his many accomplishments, Williams still encountered racism. To present himself as “less threatening” and make Whites more comfortable, Williams often walked with his hands stoically folded behind his back so that Whites would not rebuff his hand to shake. Amazingly, he also learned to sketch his designs “upside down” so those White clients who did not want him to sit beside him could view his drafts “right side up” when they instead sat across the desk from him. Incredibly determined to achieve his life goals, as a Black man, husband, father and architect, Williams refused to prove his worth to those who discriminated against him. In “I Am a Negro”, he stated that he “… developed a fierce desire to ‘show myself’. I wanted to vindicate every ability I had. I wanted to acquire new abilities. I wanted to prove that I, as an individual, deserved a place in the world.”

For certain, Williams achieved these ends. In his career, he would be responsible for designing greater than 3, 000 structures, including more than 2, 000 homes, in Los Angeles and surrounding areas of southern California. He designed homes of the wealthy and famous, including for the Hilton family, the Paleys and African-American legendary entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. His designs even graced the “eternal home”, i.e., tomb, of entertainer, Al Jolson, in Hillside Memorial Park. Williams was specifically sought and commissioned by Jolson’s widow, Erie, to design the mausoleum. Created of marble, it contains 6 pillars capped by a dome and can be prominently seen from nearby highways.

He designed houses and hotels, most notably the Bogotá Country Club, the Hotel Nutibara and the Hotel Bogotá, in Colombia. In 1947, he was chosen to design the three-million-dollar Psychopathic Unit of the Los Angeles County Hospital, marking the first time an African-American had been selected to design a large public building in Los Angeles. His work in the United States Department of the Navy during World War II led him to design public housing for war workers. His commissions included the Arrowhead Springs Hotel and Spa, the Baldwin Hills Mall, Los Angeles County Courthouse, Perino’s restaurant, the Luella Garvey House and the La Concha Motel. He collaborated with William Pereira, Charles Luckman and Welton Becket to create the amazing, futuristic Theme Building of the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX).

(No copyright infringement intended).

It was critical for him was to create for his own people in Los Angeles, most notably, his own community of West Adams. He was responsible for numerous buildings including the First AME Church, of which he was a member; Broadway Federal Savings and Loan; the Angelus Funeral Home, the Nickerson Garden Housing Project, now known as Nickerson Gardens. Williams also designed the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building. The Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company was a Black-owned business institution of paramount importance. It provided coverage to Blacks when other insurance companies, due to racial discrimination, charged exorbitant prices or simply denied coverage. It should be noted that, in 1947, Paul R. Williams helped found Broadway Federal Saving and Loan, the oldest federal African-American savings and loan company west of the Mississippi River; he served as vice-president and then director. After providing guidance and leadership for 26 years, he retired and then acted as director emeritus until his death.

Williams also collaborated with the great African-American architect and engineer, Hilyard Robinson of Washington, D.C. Together, they created several buildings, including the Engineering and Architecture Building as well as the Dental School at Howard University, a historically Black university in D.C. Also located in D.C. was the Langston Terrace that they co-designed. The Langston Terrace was the first federally-funded, public housing project created in D.C. and the second created in the United States. The housing project, as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Public Works Administration, broke ground in 1935 and took 3 years to complete. It was named in honor of John Mercer Langston, an African-American abolitionist, attorney, educator and diplomat. Langston was the first Dean of Howard Law School and the first president of Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute (presently known as the historically Black university, Virginia State University). The 274-unit complex was not only designed by Blacks but it was primarily constructed by Black laborers.

Williams and Robinson would work together again in later designing the Pueblo del Rio project in Los Angeles. Constructed in 1941, this federally-funded housing project was created under the dominion of the National Housing Administration. Located in the Central-Alameda neighborhood of southern Los Angeles, it was designed to house military veterans and working-class laborers, many of who were African-Americans.

The design styles of Paul R. Williams were incredible and diverse; in designing true luxury, he beautifully and elegantly balanced function, comfort and style. He referred to his designs as “conservative modern”, as they would remain relevant and appealing much longer than the latest trends that would soon tire and expire.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In an article, “A Man of the Grandest Design: Paul R. Williams”, author Bluebeam of Struxur remarked on Williams talents, skills and industry. They heralded, “A master of Georgian and Colonial American styles, Williams was equally at home designing Spanish Colonial, Tudor Revival, French Chateau, Regency, French Country, Mediterranean and even post WWII Modernism style structures. His style made him the go-to designer for the Hollywood elite. The world-renowned Beverly Hills Hotel received a Williams upgrade, including its signature pink and green colors and iconic script logo, as well as the famed Polo Lounge. Celebrities and public figures who sought out his services include Frank Sinatra, Cary Grant, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Barbara Stanwyck, Charles Correll, Bert Lahr, Tyrone Power, Will Hays, Zasu Pitts, Danny Thomas and Lon Chaney. With the warmth of Southern California as a backdrop, Williams pioneered indoor and outdoor living with the harmony of patios as extensions of the house, hidden retractable screens, sweeping staircases, modernist interior fireplaces and master suites.”

His work with singer/producer/actor Danny Thomas, best known for his on-screen role as “Danny Williams” in Make Room for Daddy (also known as The Danny Thomas Show), however, was more than professional. Thomas was also a philanthropist who founded the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, whose creation is centered upon, according to the National Shrine of St. Jude, that “no child should die in the dawn of life”. Since the loss of Paul Jr., he personally understood the mission of Thomas. In 1951, Williams offered to design, for free, an integrated 1,000-bed hospital that was to be located in the South. In 1962, when the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital opened in Memphis, I am sure that a sense of resolution was felt by Williams. He was able to honor his son as well as his father, who was of Memphis, with his work. In fact, the Peabody Hotel, where Williams’ father had worked as a head waiter, hosted the 10-year anniversary of the hospital.

Paul Williams earned numerous accolades for his extensive professional and community and his community outreach. These accolades include 3 honorary doctorate degrees: an Honorary Doctor of Science (Lincoln University of Missouri, 1941); Honorary Doctor of Architecture (Howard University, 1952); and Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts (Tuskegee Institute, 1956). A member of Sigma Pi Phi, the oldest African-American, Greek-lettered organization, Williams was awarded “Man of the Year” in 1915 by Omega Psi Phi, another African-American, Greek-lettered fraternity. In 1953, he was awarded by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) the Spingarn Medal for his outstanding contributions as an architect and active member of the African-American community. In 1957, Williams was the first Black to be inducted as a Fellow into the College of Fellows of the AIA. In 1962, Ebony designated Williams as one of “America’s 100 Richest Negroes.”

Williams continued to design until his retirement in 1973 and the following year, AIA elected him to “Emeritus” status. Due to complications caused by diabetes, he would pass away on January 23rd, 1980, at the age of 85 years old. He was interred in the Sanctuary of Radiance, Manchester Garden Mausoleum at Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood, California. His widow, Della Mae, would survive him 16 years, passing away July 24, 1996, at the age of 100 years old; she is interred with Paul. Mrs. Williams is a co-founder of the Wilfandel Club, the oldest African-American women’s club in Los Angeles. The club, founded in 1945, has the goals, according to their website, “of promoting civic betterment, philanthropic endeavors and general culture”.

The complicated and ugliness of racial inequity in America still impacted the work of Williams, even after his death. In 1992, the Los Angeles police officers who were charged in the savage beating of African-American Rodney King were acquitted. Their acquittal led to the LA riots, during which many African-Americans destroyed so many parts of the community. One of these parts was the Broadway Federal Savings and Loan building in Watts. As an institution co-founded and administered by Williams for 33 years (1947-1980), it held his career archives, including drawings, notes, business records, images, articles and letters. Tragically, his archives were destroyed when the building was burned down.

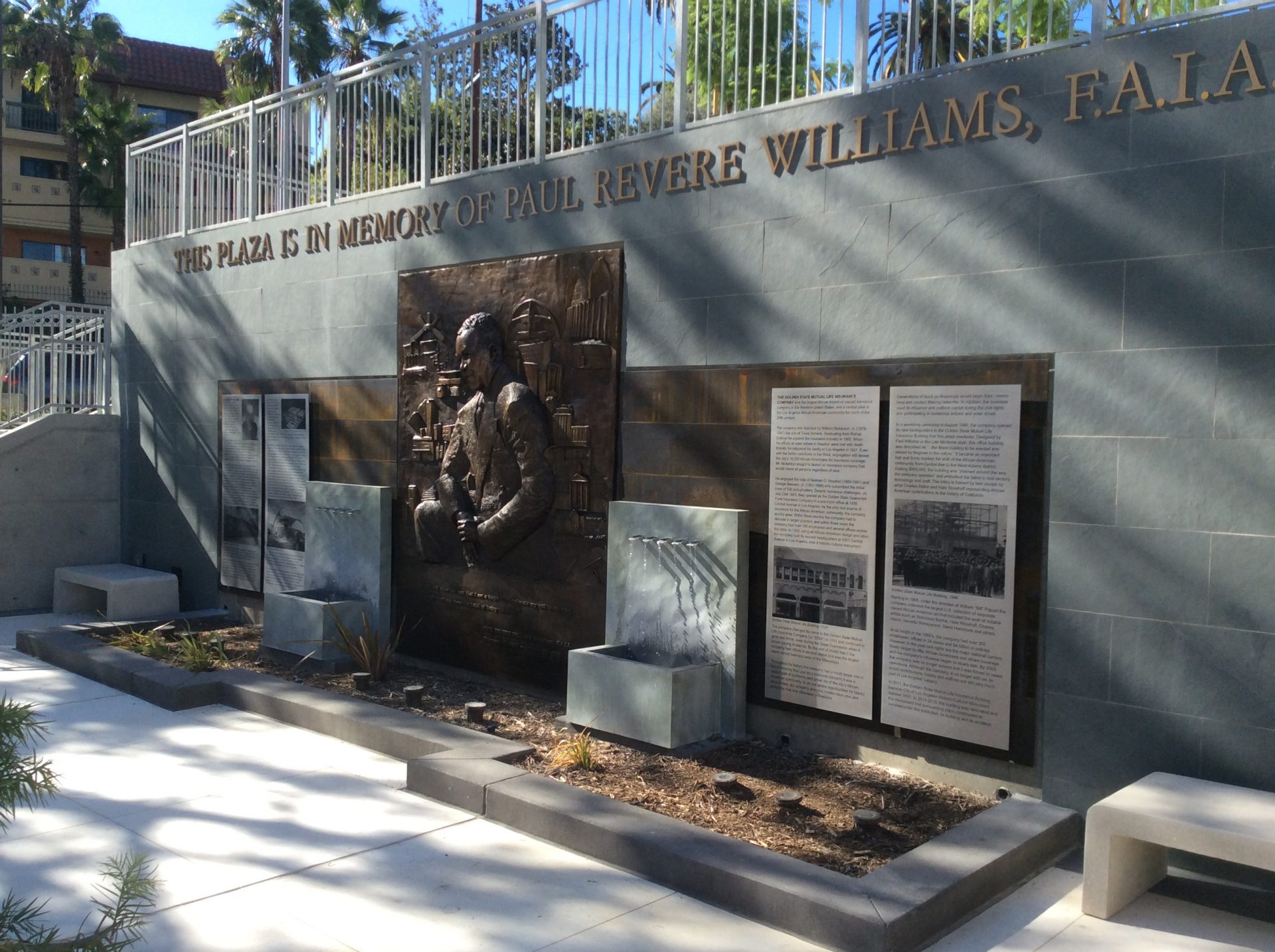

In 2015, a memorial plaza and monument were dedicated, honoring Paul Williams and his amazing work. Its carefully-selected location in the historic West Adams neighborhood, just north of the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building that Williams designed in 1949, is most appropriate. The monument contains a 9-foot bas relief of bronze and depicts Williams centered in the foreground; images of 23 structures that he designed border both sides.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Created by a local artist, Georgia Hanna Toliver, the monument features a biography of Williams. It also highlights the history of the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company, which, at one time was not only the largest Black-owned insurance company in the western United States, but it was the largest Black-owned business west of the Mississippi River! The insurance company was founded by African-American entrepreneur William Nickerson, Jr. The Nickerson Gardens in Los Angeles was named in tribute to him and his contributions to the city. Created by Williams in 1955, it contained 1,066 apartment units, rendering the Nickerson Gardens as the largest public housing complex west of the Mississippi River.

In 2017, Paul Williams was honored posthumously by the AIA in being awarded the Gold Medal. According to the AIA website, this award is “the highest annual honor recognizing individuals whose work has had a lasting influence on the theory and practice of architecture. This award was given by William J. Bates, FAIA, the elected president of AIA to serve in 2019, who felt that Williams best embodied the principles supporting the honor. Bates stated that the recognition of Williams signaled a cultural shift towards greater professional and institutional equity.

However, Bates was only the second African-American to hold this position (the first, Marshall E. Purnell, FAIA, was elected to serve as president for 2008) in the 90,000-member professional organization that began in 1857. In additions, African-American women architects comprise a mere .03 % of licensed architects in the United States. Much still must be undertaken to achieve equity that is authentic and relevant for Black architects. Thankfully, measures to engage, support and promote Blacks in the field of architecture have been created and thrive. These measures include professional organizations for Blacks architects, symposiums in public forums and mentoring.

The impact and influence of Paul Revere Williams is beyond amazing. His determination to create and excel in his passion, despite obstacles of racism and discrimination, has left an immeasurable impact throughout the world.

Planning is thinking beforehand how something is to be made or done, and mixing imagination with the product – which in a broad sense makes all of us planners

Paul R. Williams