Founded in 1991, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM) is, according to its website, “the world’s only museum dedicated to preserving and celebrating the rich history of African-American baseball and its impact on the social advancement of America.” Privately funded, the NLBM was established in 1990 and is presently located at 1616 East 18th Street in the historic 18th & Vine Jazz District in Kansas City, Missouri.

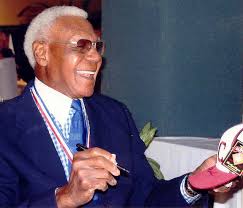

The NLBM began in 1991, under the guidance of several, including historian Larry Lester, NLB player Alfred Surrat and NLB player and manager Buck O’Neil, who were concerned with preserving the rich legacy and vast contributions of Blacks to baseball and American culture. Originally housed in a one-room space within the Lincoln Building of the Jazz District, in 1994, the museum moved to a two-thousand square-foot space.

In 1997, under the leadership of O’Neil, who served as its chairman, the NLBM moved into its new ten-thousand square-foot home, where it is currently. It is conjoined with the American Jazz Museum inside a twenty million-dollar cultural complex known as “The Museums at 18th & Vine”.

The NLBM, having received greater than two million visitors, has, as its site states, “… become one of the most important cultural institutions in the world for its work to give voice to a once forgotten chapter of baseball and American history. In … 2006, the NLBM gained National Designation from the United States Congress earning the distinction of being ‘America’s National Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.’”

Blacks began playing on baseball teams, first in amateur leagues, as early as the 1850s. The first baseball game, on record, was played between two Black teams of New York City. Occurring on November 15, 1859, it was between the Henson Base Ball Club, who would be the victors, and the Unknowns. After Reconstruction, Blacks, many who had served during the Civil War, began to form, manage and promote their own teams, including the Albany Bachelors and the Philadelphia Excelsiors. These teams formed in mid-Atlantic states and along the east coast, areas where African-Americans had begun to settle. Philadelphia, for example, had a prominent population of African-Americans and the city became a mecca for Black baseball. Due to racial discrimination, the Black baseball teams were barred from playing at professional fields and stadiums. Octavius Catto, the promoter of the Pythian Base Ball Club of New Jersey, discovered that legalized segregation and racial prejudice excluded Blacks, individually and in baseball clubs, from membership in professional baseball associations.

By the 1870s, Blacks were allowed to play professionally and the first professionals include Bud Fowler and the brothers, Moses Fleetwood Walker and Welday Wilberforce Walker. In 1885, the first nationally-known Black professional baseball team, the Cuban Giants, was created when three Black clubs consolidated; they were the Keystone Athletics of Philadelphia, the Orions of Philadelphia, and the Manhattans of Washington, D.C. The Cuban Giants was comprised of only African-American players; the name “Cuban” was selected because it appealed to White patrons in Cuba, who were fans of the Black players.

The Cuban Giants were so successful, that a new Negro league, the National Colored Base Ball League, was formed in 1887. This new league, led by Walter D. Brown, was a minor league that consisted of the Baltimore Lord Baltimores, Boston Resolutes, Louisville Falls Citys, New York Gorhams, Philadelphia Pythians, Pittsburgh Keystones, the Cincinnati Browns and Washington Capital Cities. The last two teams never played. While the league’s status protected them from stipulations inherent in major league baseball, it also sequestered players to play, season after season, only for the team they signed; the league would not endure.

Racism, bolstered by Jim Crow laws, continued to proliferate in society and by the early 1900s, Blacks, significantly Andrew “Rube” Foster, sought greater control and equity in baseball. Formerly a pitcher for the Cuban X Giants, Foster was hired in 1904 by Walter Schlichter, a White entrepreneur who owned the Philadelphia Giants, a Negro league baseball team. Foster was hired to lead, and hopefully, defeat, the Cubans, who had defeated Philadelphia in the 1903 “Colored Championship”. Foster would lead Philadelphia to become a top-tier team until his departure in 1907. He left to play and manage the Leland Giants, who were led by Frank Leland, a Negro league player, manager and club owner of Chicago, Illinois.

Black ownership and management in baseball was essential if the Black players were to advance. Nat Strong, a White businessman, was a leading promoter of Black baseball. An owner of many baseball fields in New York City, he earned a percentage of every game that was played on his field. However, he severely limited the opportunities and growth of the Negro League team, the Brooklyn Royal Giants, until almost nonexistence. Strong then bought the team at a drastically diminished cost and turned it to a barnstorming team.

Foster began to implement stellar professional practices, on the field and in management, including being able to secure forty percent of the gate; Leland’s percent had only been ten percent. As Tim Odzer wrote in his article, “Rube Foster”, he was so much greater than a baseball player because “Foster’s ambitions in baseball went beyond simply being an amazing talent on the mound, but extended into the dugout and eventually the front office.” In 1907, Foster’s pitching led the Leland Giants to a season of 110 wins, earning the Chicago City league championship. In 1909, Foster & Leland could not agree on roles each was to play within the baseball club and went to court over it. In 1910, Foster was able to create his own team, which consisted of players he recruited from both the Philadelphia Giants and Leland Giants. Ultimately calling his team, the “Chicago American Giants” to increase the team’s appeal to baseball fans, Foster pitched and managed these Giants to an astounding record of 128-6.

At this time, Foster began talking about reviving the concept of an all-Black league. Looking at examples such as Strong, Foster was adamant that Black teams should be owned, managed and promoted by Black men. Also in 1910, former White baseball player J.L. Wilkinson started the All Nations team, which was a multinational, multiracial and multi-ethnic team. The All Nations team would eventually become the Kansas City Monarchs, one of the most popular teams of the Negro Leagues.

Excluding a 1916 defeat to the Indianapolis ABCs, the Chicago American Giants won the Western League Championship from all seasons between 1910 and 1922. Although Foster experienced personal success, he noticed the obvious lack of a national Black baseball league and its accompanying championship. Foster began to initiate talks with other Black baseball club owners to ascertain how best to advance Black baseball but they were unable to collaborate.

Upon the entry of the United States into World War I in 1917, labor positions previously held by White men were now open. The availability of work spurred the Great Migration of African-Americans from the rural South to the industrialized North. Because of this great influx of Blacks who attained work in cities such as Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, Indianapolis, New York City and Dayton, a larger and more affluent fan base was created.

In 1919, the ending of World War I and occurrence of race riots in response to racial discrimination within industrialized centers such as Chicago, further cemented Rube Foster’s determination to improve life for Blacks. Foster’s determination led to his February 1920 meetings with the owners of eight Black teams at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City, Missouri. The original team members were the Chicago American Giants, Chicago Giants, Cuban Stars, Dayton Marcos, Detroit Stars, Indianapolis ABCs, Kansas City Monarchs and St. Louis Giants. From this meeting came the creation of a Negro National League and its governing body, the National Association of Colored Professional Base Ball Clubs. Foster was elected the first league president, treasurer and booking agent, all while managing his own team, the Chicago American Giants.

While some may have felt Foster showed favoritism to certain teams, players or conditions, Foster’s unwavering commitment and incredible dedication to Black baseball and its players was commendable and unsurpassed. As Odzer wrote, “Foster was a well-respected leader who turned Black baseball into a successful enterprise; his devotion to the league was incredible, and he often helped teams in poor finances out by paying their payroll out of his own pocket. Teams such as the Chicago American Giants and Kansas City Monarchs often were more profitable than White baseball teams, which helped spawn Black baseball leagues in the south and the east. Foster’s tenure as president laid the groundwork for the future success of the Negro Leagues.”

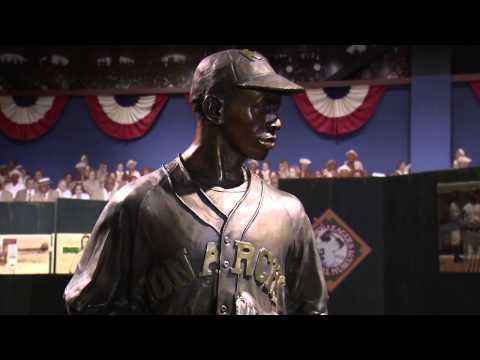

The NLBM operates two blocks from the Paseo YMCA where Andrew “Rube” Foster established the Negro National League in 1920. A site on the National Register of Historic Places, that building is located two blocks away from the NLBM at 18th & Vine. The museum recreates the look, sounds and feel of the game’s storied past. Video presentations and memorabilia in the 10,000 square-foot multimedia exhibit chronicle the history and heroes of the leagues from their origin after the Civil War to their end in the 1960s.

In a 2011 article, “Preserving Key Baseball Legacy is Not Easy”, of The Wayback Machine, journalist Reid Forgrave spoke with Bob Kendrick, who was the museum’s director. In discussing its history and impact, Kendrick stated, “The museum weaves together the story of the Negro Leagues and the story of race in America. You can learn about how Cap Anson, a virulent racist and one of the best ballplayers of the late 1800s, led the charge to ban black ballplayers at the same time America turned its back on Reconstruction. You can learn how the Negro Leagues became the most successful black business in America but collapsed after integration. It’s a story of how one sport reflected a country’s attitudes on race – and then, with Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier in 1947, how America’s Pastime became a precursor for the Civil Rights movement.”

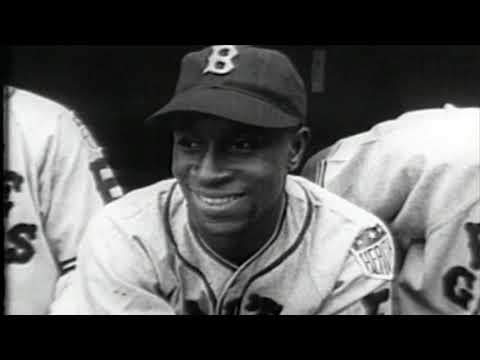

Visitors to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum will experience exciting features that include parallel timelines of the Negro Leagues and American history as well as a documentary narrated by acting & voiceover great, James Earl Jones, on the history of the Black baseball teams. They can view exhibits containing hundreds of photographs, historical artifacts, several interactive stations and the Coors Field of Legends bronze sculptures. There is also a set of lockers in tribute to Negro National Leagues players, such as James “Cool Papa” Bell, Josh Gibson, Leroy “Satchel” Paige, William Julius “Judy” Johnson, Martin Dihigo, Oscar Charleston and John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, who have been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

This set of lockers is a fitting tribute, considering that Negro Leagues players were not allowed to be inducted into the Hall of Fame until 1971, and that was not without controversy. One of the first to publicly speak about the racial discrimination shown towards the Black baseball players was Ted Williams, a White, left-fielder who played his entire professional career for the Boston Red Sox. Considered to be one of the greatest players in this history of American baseball, Williams spoke of the exclusion of Negro Leagues players during his 1966 induction into the Hall of Fame, lamenting, “The other day, Willie Mays hit his five hundred and twenty-second home run. He has gone past me, and he’s pushing, and I say to him, ‘Go get ’em, Willie.’ Baseball gives every American boy a chance to excel. Not just to be as good as anybody else, but to be better. This is the nature of man and the name of the game. I hope someday Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson will be voted into the Hall of Fame as symbols of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren’t given the chance.”

Five years later, in early 1971, baseball commissioner, Bowie Kuhn, announced that former Negro Leagues players will have a separate wing in the Hall of Fame. Satchel Paige, according to writer Bill Chuck in the article, “Negro League Players in the Hall of Fame”, strongly stated: “I was just as good as the White boys. I ain’t going in the back door of the Hall of Fame.” Due to the controversy of and protest to the announcement of the Jim Crow arrangement, in July 1971, the former Negro Leagues legends would be included and honored, as their White counterparts were, in Hall of Fame.

From 2000 to present, the NLBM regularly gifts the Legacy Awards, which honor Black, modern professional baseball players, managers and executives in the National and American leagues for accomplishments characteristic of a Negro Leagues legend. The Hall of Game Award was established by the NLBM on February 13, 2014, the anniversary day of the founding of the NLBM. According to the museum’s website, the Hall of Game, “annually honors former Major League Baseball (MLB) stars who played the game with the same passion, determination, flair and skill exhibited by the heroes of the Negro Leagues.” Those inducted in the Hall of Game will also receive permanent recognition in the forthcoming Buck O’Neil Education and Research Center. This center, under development by the NLBM, will be located at the site of the Paseo YMCA, the birthplace of the Negro National League. The categories of the Legacy Awards are, according to the NLBM website, are as follows:

- Hall of Game Award – Former Major League Baseball stars

- Oscar Charleston Legacy Award – “Most Valuable Players”

- Leroy “Satchel” Paige Legacy Award (2000–2005) – “Pitchers of the Year”

- Wilbur “Bullet” Rogan Legacy Award (2006–present) – “Pitchers of the Year”

- Larry Doby Legacy Award – “Rookies of the Year

- Hilton Smith Legacy Award – “Relievers of the Year”

- Walter “Buck” Leonard Legacy Award – batting champions

- Josh Gibson Legacy Award – “Home Run” leaders

- James “Cool Papa” Bell Legacy Award – “Stolen Base” leaders

- Charles Isham “C. I.” Taylor Legacy Award – “Managers of the Year”

- Andrew “Rube” Foster Legacy Award – “Executives of the Year”

- Kansas City Monarchs Award – Royals player and pitcher of the year

- John Henry “Pop” Lloyd Legacy Award – “Baseball and Community Leadership”

- Sam Lacy Legacy Award – “Baseball Writer of the Year”

- Jackie Robinson Lifetime Achievement Award – “Career Excellence in the Face of Adversity”

- John “Buck” O’Neil Legacy Award – to a local or national corporate/private philanthropist for “Outstanding Support of the NLBM”

Guests to the museum may participate in any of its events, such as “Jazz and Jackie”, that salutes Jackie Robinson’s roots in Kansas City and his love of jazz music. They may join in the family friendly, “Heart of America Hot Dog Festival”, which simultaneously celebrates the sandwich and America’s favorite past time. There is also the “Dressed to the Nines” event, which is the best dressed day in baseball. Historically, Black churches would start earlier than normal, so its members may attend Negro Leagues baseball games. Because they would be leaving church, they often wore their “Sunday Best”. Additionally, there are a golf outing and a three-day celebration, including a fashion show, in tribute to Buck O’Neil and his vision for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

If you are unable to make any of these events, please try to grab a bite at Arthur Bryant’s Barbecue, one of the most famous barbeque restaurants in the United States, located a few blocks away from the museum. Many Negro Leagues personnel, fans and museum visitors love the delicious fare of the late African-American purveyor of Kansas City barbecue.

Whether you are a fan of Black culture, baseball, American history or a combination of all three, visiting the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum is a must and a privilege. Knowing about and honoring the Negro Leagues are essential, as Kendrick said to Forgrave in their interview, because “it’s about America at its worst but also America at its best, because it shows the American spirit.”