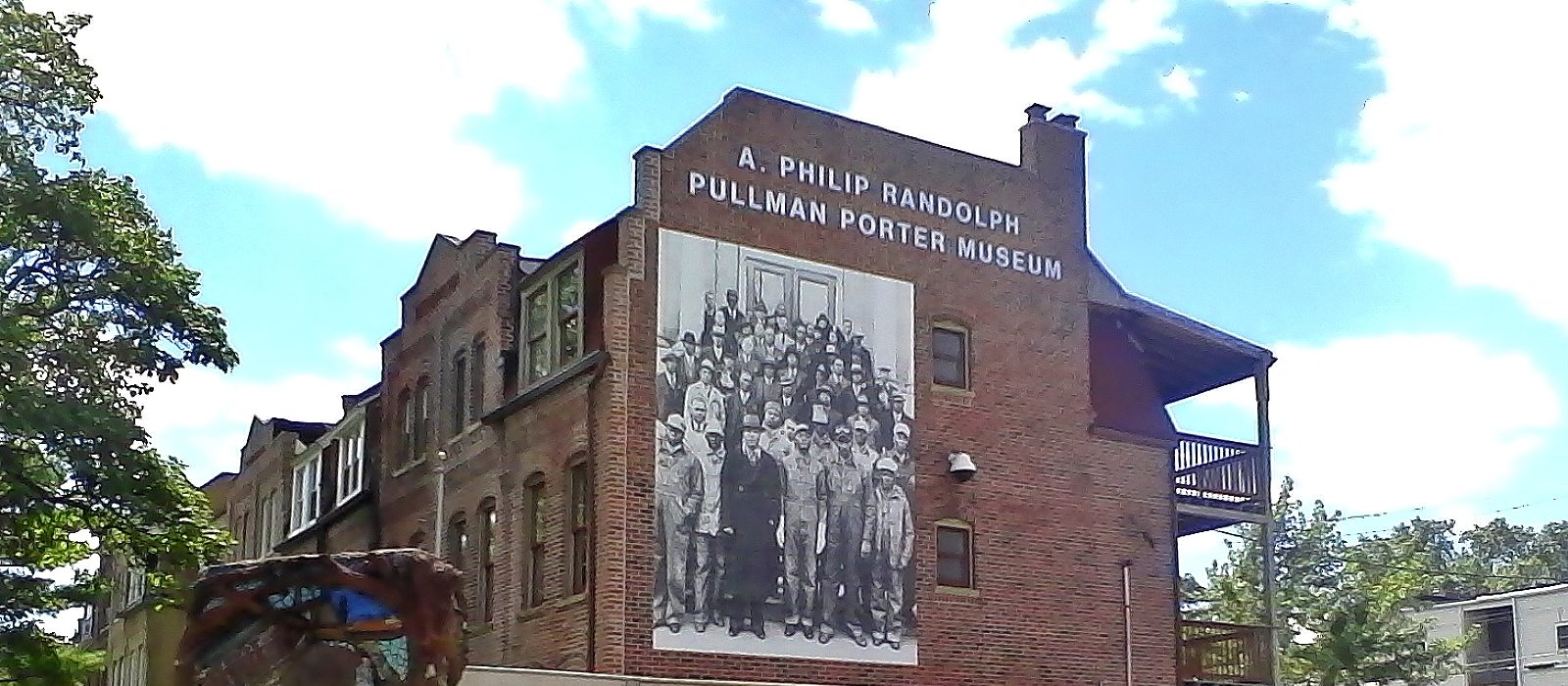

Founded by Dr. Lyn Hughes in 1995, the National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum (NAPRPPM) is located in the Historic Pullman District in Chicago, Illinois. The museum is named in honor of Asa Philip Randolph and the Pullman Porters, Black men who comprised the membership of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) labor union.

The building in which the museum is housed is an original rowhouse that was one of many constructed by George Pullman. Pullman had these homes built in order to rent to the White workers of his railroad car company, The Pullman Car Company. This “community” was not created solely from Pullman’s beneficence, but also to recoup some of the monies paid to his workers. Because the National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum is housed in this rowhouse, it is part of Pullman National Historic Landmark District of the U.S. Department of the Interior. The museum holds a collection of primary documents, videos, books and artifacts. However, the NAPRPPM also has been developing a national registry of Black employees who worked for the Pullman Company from 1863, during the Civil War, to 1969, after the Civil Rights Movement.

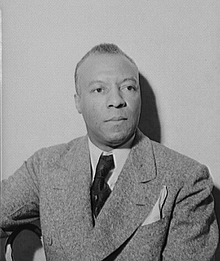

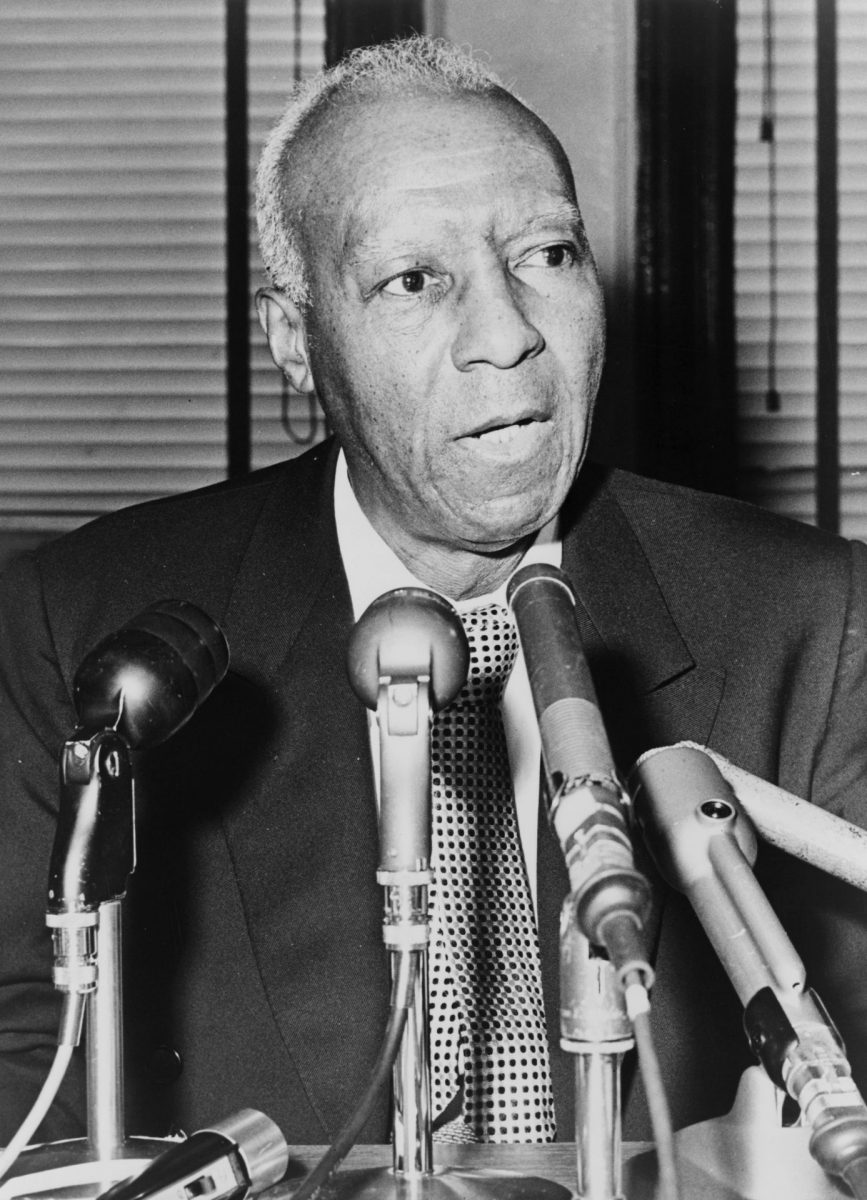

Randolph, whose previous positions of employment included elevator operator, waiter and porter, co-founded the BSCP and served as the union’s president for forty years. As its chief organizer, Randolph fought for more than ten years against the Pullman Car Company, one of the most powerful corporations in the United States. His efforts ultimately led the BSCP becoming certified to represent the Pullman porters, making, in 1937, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters the first Black labor union in the United States to win a collective bargaining agreement. This is an especially significant achievement because the Pullman Company employed more than twenty-thousand Black BSCP members, rendering it the largest private employer of Black labor.

Randolph and the BSCP’s efforts created a blueprint for the next generation of African-Americans who continued the fight to attain civil rights not just in the workplace, but also in the military. The techniques of utilizing economic potential, nonviolence and mass protest that Randolph and the BSCP incorporated in their fight against the Pullman Company would be the model that many civil rights activists of the 1950s and 1960s would select to emulate.

In order to comprehend the immense value of the National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum, the history, struggle, perseverance and accomplishments of Randolph and the porters in a racially-discriminate work force and society must be examined.

This was an era when, trains were the ultimate in technology, speed and glamor. In order to attract transport freight and passengers, train companies competed for customers. With increased access to travel, especially cross country, came passenger the demand for greater creature comfort.

Entrepreneur George Pullman of Illinois sought to meet this demand by creating high quality coaches and luxury railroad cars for lease to railroad companies. They were so luxurious that they were referred to as “rolling hotels on wheels” and the phrase, “traveling Pullman”, meant to travel in high style. However, it was not just the extravagantly appointed cars that prompted the sale of these expensive tickets; it was the superb personal service of the Pullman porters, who, as service personnel, was locked in the leases to the railroad companies.

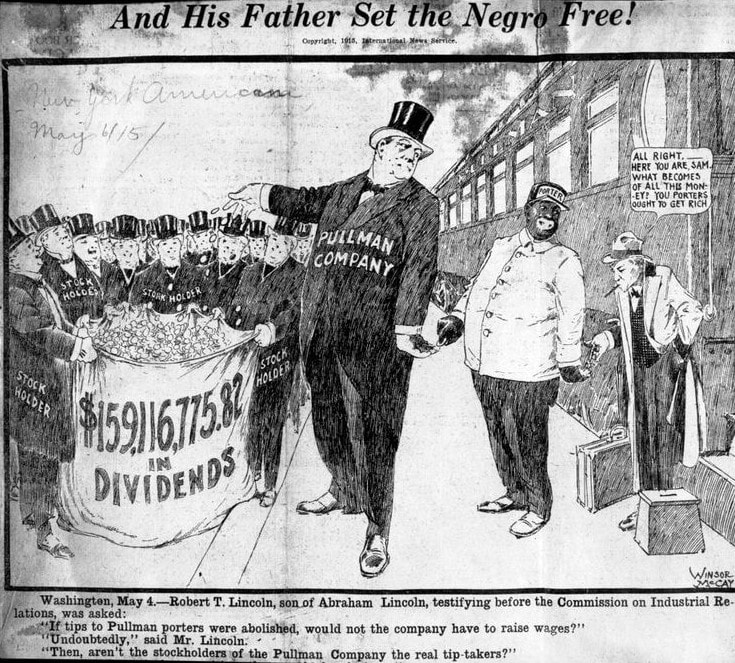

With the Panic of 1873, followed by the Depression of 1893, Pullman lowered the porters’ meager wages even more, drastically impacting Black workers in his company, and he refused to lower rent in Pullman, his housing community of White workers. His refusal prompted the Pullman strike of 1894. Riots broke out throughout the country, but Pullman porters were not involved in the strike. In fact, they continued to work ceaselessly!

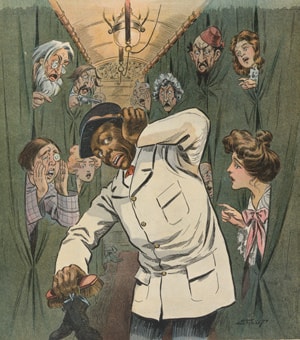

Pullman intended his railroad cars to cater to those of the upper echelon and his cars were celebrated for their luxury and comfort. The men who were hired as conductors and ticket sellers were White; those who provided service as the porters were Black men.

In the beginning, these porters were formerly enslaved Black men who had been specifically recruited by the Pullman company. These Black men were due to their prior experience of providing “service” as well as the White travelers’ desire, in wanting to cling to the personal and social customs of slavery, to be catered to and waited on by Blacks still, despite the end of slavery.

According to Larry Tye, author of Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle-Class, luxury sleeper car innovator George Pullman had sought these African-American men purposely to cater to the demands of wealthy White travelers because “they had spent their entire life doing what their masters had told them and what George Pullman envisioned was that when they went out on the rail cars, they would do the same things for his customers.” In a 2009 interview by Michele L. Norris of National Public Radio (NPR) with former cook and porter, Frank Rollins, 93, he recounted that “… the railway wanted Southern boys to run the dining cars because ‘they thought they had a certain personality and a certain demeanor that satisfied the Southern passengers better than the boys who came from Chicago.’”

The porter had to do everything from greeting passengers; carrying baggage; making up sleeping berths; to cleaning the cars; cooking and serving meals; and shining shoes. They were paid very poorly, earning $1 dollar per day and working 21 hours per day, 7 days a week. Because of the low pay, the porters had to depend upon tips to earn a living. These Black men had to be on call night and day to service the passengers and spent long periods of time away from their loved ones.

Hughes spoke of the numerous sacrifices made by the Pullman porters in the documentary, based upon Tye’s book. In the film, Hughes asserted that these Black men were “required to work 400 hours per month … or 11,000 miles, whichever came first … the pay was about $60 per month. From that pay, $33 went towards the expenses they incurred … they had to buy their supplies, nothing was given to them, the towels that they used, the sheets that they used …”

The economic separation, deprivation, and marginalization of the Black community forced by Jim Crow and the doctrine of advancement through self-reliance preached by Booker T. Washington led many Black leaders to look with distrust on joining with Whites on issues of common concern. They often denied that Blacks and Whites had any common interests at all. Furthermore, and foremost, racial discrimination remained entrenched in almost every institution that existed in the United States, and these racist beliefs and practices, both subtle and overt, empowered the White labor movement to bar the Black workers and their efforts to organize by whatever means necessary. The Pullman porters were intimidated & threatened with lower wages, violence, loss of jobs and some even fired for attempting to form a union.

Porters suffered long hours of work; low pay; taxing work; diminished hours of sleep; 24 hours/day on call responsibility; excessive absences away from loved ones and Pullman’s severe code of conduct. Because these Black men worked much longer hours under more stressful conditions than their White counterparts for less than half the pay and also were excluded from certain positions, the porters attempted to form a union in 1909. The Pullman porters were intimidated and threatened with lower wages, loss of jobs and some even fired for attempting to form a union.

After many discussions, three men representing the porters met with Asa Phillip Randolph. A. Philip Randolph was highly supportive of the Pullman porters and their plight, covering articles on them in a magazine, The Messenger, of which he was a co-founder+publisher, with Chandler Owen.

Randolph, who had been unsuccessful four previous times as an organizer, was sought because he was actively supportive but also because he was astute, highly articulate and unable to be threatened, employment-wise, by the Pullman company. Randolph accepted their request to lead them and on August 25, 1925, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was founded. Their motto was “Fight or Be Slaves!”

The forming of the BSCP was critical because by the 1920s, Blacks were employed by Pullman as porters but also as dining car waiters, lounge car attendants and onboard servers as well as firemen, maids, and railcar attendants. With over 20,000 BSCP members employed by Pullman, these Blacks comprised the largest category of Black labor!

Randolph worked tirelessly, despite constant threats and consistent attempts to bribe him. He firmly stood his ground and was considered by many, especially President Franklin D. Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, to be of great integrity.

In 1937, the Pullman Company finally recognized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, signed a labor agreement to reduce their hours and increased the pay of these men. A. Phillip Randolph made possible the first African-American labor union in the United States and the BSCP’s defeat of the Pullman company was an absolutely incredible feat that would set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement.

The BSCP had laid the foundation in fighting for and attaining civil rights in the workplace. These brave members also politically, and often financially, supported civil rights organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Of significance, the original “March on Washington” was organized by Randolph in 1941, 22 years before the historic one he chaired in 1963. It was canceled due to the passage of the Fair Employment Practices Act by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who actively supported Randolph and the BSCP in their quest for better pay and better benefits.

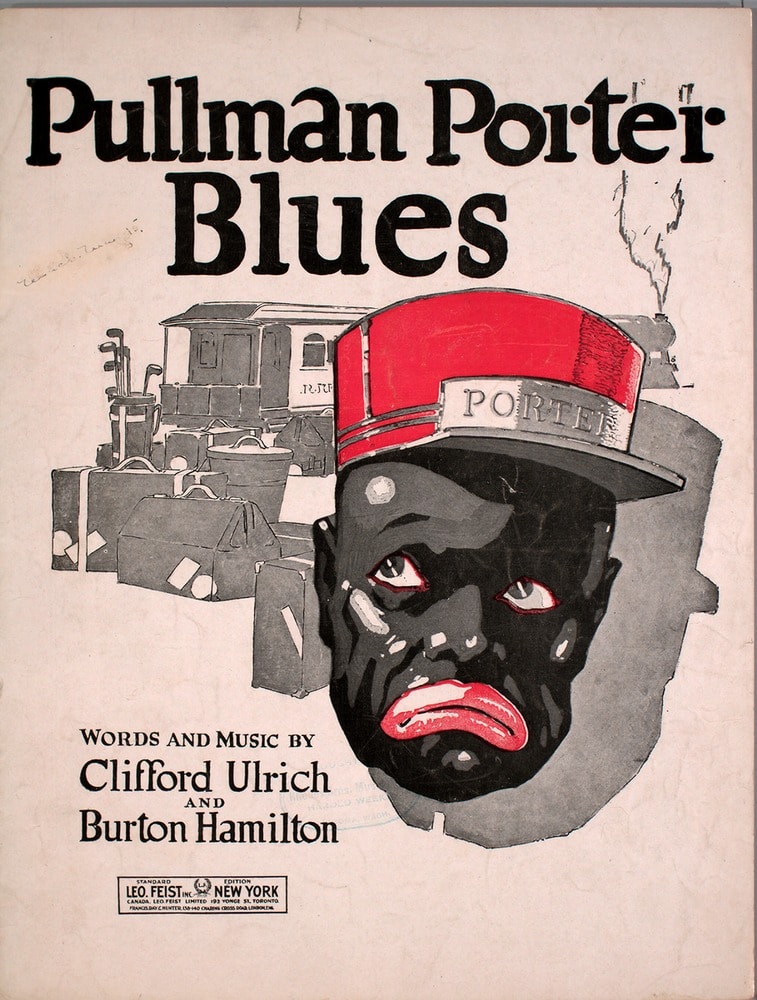

Despite their extreme professionalism, the porters were often portrayed in the media in negatively racial stereotypes and denigrated in music, stage and film. Additionally, numerous porters excelled in their own talent and skills, several even becoming famous. They include explorer Matthew Henson; film pioneer, Oscar Micheaux; cowboy and hero of the old West, Nat Love; and photographer and filmmaker, Gordon Parks, Sr.

With great sacrifice, the Pullman porters supported their families, their communities and institutions. Many saved, even during The Great Depression, in such a manner, that it is proposed by Tye that they created “The Black Middle Class”, socioeconomically, educationally & politically. Because of the economic stability of many, they provided their loved ones with opportunities for a greater quality of life, including sending their children on to higher education.

For greater than 100 years, 1858-1969, these outstanding Black men provided stellar service, working on trains traveling throughout the States, despite extreme adversity. They fought valiantly against obscene prejudice and discrimination in a racially-segregated work environment … as the nation’s first Black labor union, members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters developed the foundation for Black labor unions, the Black middle class and for the Civil Rights Movement!

Because of their contribution to society, the creation of the NAPRPPM was essential in a greater understanding American history, democracy, economics, and culture by educating the public about the massive contributions of African Americans, A. Philip Randolph and the Pullman porters. On February 19, 2015, President Barack H. Obama designated the Historic Pullman district of Chicago, Illinois as a National Monument. As a site in this district, the National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum is now a part of the National Park Service.

As the website of the NAPRPPM proclaims, “Randolph demanded that African-American people be fully and equally included in American society. A. Philip Randolph was an articulate, intelligent, and fair leader who devoted decades of his life to his vision of a more moral and civilized American society. A Philip Randolph was a great man, a great humanitarian, and a great American!”

In 2008, Amtrak, in their partnership with the NAPRPPM honored the Pullman porters in Chicago. The following year, Amtrak celebrated the Pullman porters in Oakland, California, as Oakland was the location of a significant chapter of the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters. C.L. Dellums, who, in 1929, was elected as the national vice-president and, in 1966, as the president of the BSCP, headed the Oakland branch. Also, in 2009, the city of Philadelphia honored the Pullman porters as part of National Train Day.

The museum is open Thursday through Saturday and their walk-in hours are 11am to 4pm. It allows for self-guided tours and group tours as well as custom tours, which are available by appointment. Additionally, the facility is available for rental.

An accommodation of outreach that is available for rental is their traveling exhibit on A. Philip Randolph and the Pullman porters. The exhibit, which spans from the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, details the contributions of these great Black men beyond the railroad and how they built diverse aspects of the Black community.

The museum also has an archive collection; however, it is only available to staff, as they are upgrading their content for alignment with accessibility and documentation policies. It has an active community outreach program, presents opportunities for volunteerism, produces a radio program and houses a gift shop. All these supports the National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum, presently, the only museum in the United States devoted to Black labor history!