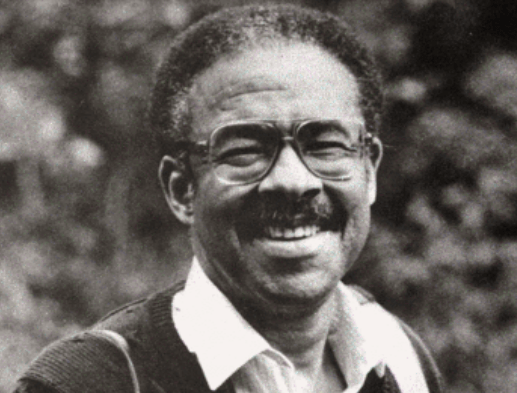

“While others of us see things through the naked eye, Sleet saw things through his soul … Sleet was able to see the genuine in others because he was genuine.”

~ Rev. Dr. Norman M. Rates, professor of religion, Spelman College

On Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1926, in Owensboro, Kentucky, Moneta Sleet, Sr. and Ozetta Sleet (née Allensworth) welcomed a son, Moneta, Jr. When he was a young child of nine or ten years, he was gifted by his parents a box camera. This gift would spark a love for photography that would last throughout Sleet, Jr.’s life.

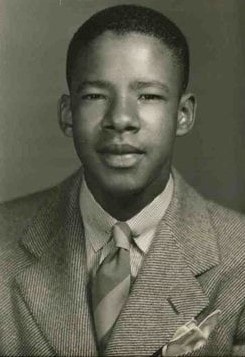

An inquisitive learner, Moneta Sleet, Jr. graduated from Western High School, where he was a member of the camera club and editor of the school’s newspaper. While there, he became intrigued with photography, commenting in his book, Special Moments in African American History: The Photographs of Moneta Sleet Jr., 1955-1996, that “We would go into the makeshift darkroom in a little bathroom and develop pictures … And I became fascinated by it.”. He then attended Kentucky State College (presently known as Kentucky State University), a historically Black university located in Frankfort, Kentucky.

(No copyright infringement intended).

His academic studies were interrupted by his enlistment into an all-Black unit of the U.S. Army, which would serve during World War II. During his term, he was stationed in Burma and India. Upon completing his service, Sleet, Jr. returned to Kentucky State College, where he decided to switch his major from business to photography. This change arose from his working as an assistant at a commercial studio that Dr. John H. Williams, a college dean operated, making real the possibility that he could work as a professional photographer. In 1947, Moneta Sleet, Jr. graduated cum laude from Kentucky State College and moved to the East Coast.

There, he took photography courses in the School of Modern Photography at New York University, from where he would graduate in 1950 with his Master’s degree in Journalism. That same year, he married Juanita, who he affectionately called, “Neet”, and they had three children: two sons, Gregory and Michael; and a daughter, Lisa.

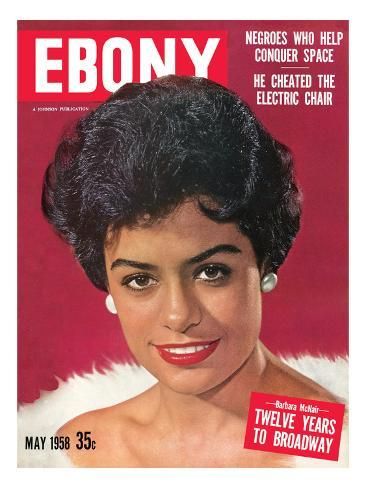

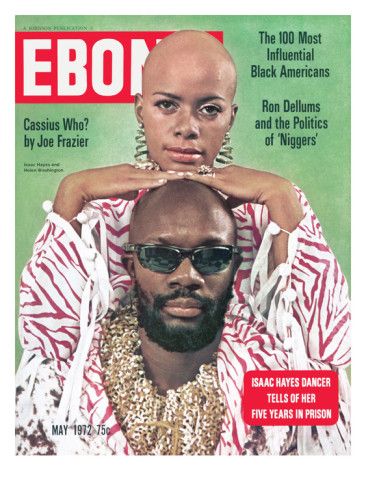

Moneta Sleet, Jr. worked for a brief time as a sportswriter for The Amsterdam News, a newspaper, before securing a position at Our World, a popular magazine. When Our World closed, John H. Johnson, of Chicago, acquired its assets. Johnson was the founder of Johnson Publishing Company, whose publications included Ebony and Jet. Discovering and admiring the work of Sleet, Jr., he hired the photographer in 1955 to work with him; they would work together for forty-one years. The Amsterdam News, Our World and all those of Johnson Publishing Company were Black publications.

At Johnson Publishing Company, Moneta Sleet, Jr. traveled across the United States and throughout the world, including Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Libya, the Sudan and in parts of South America.

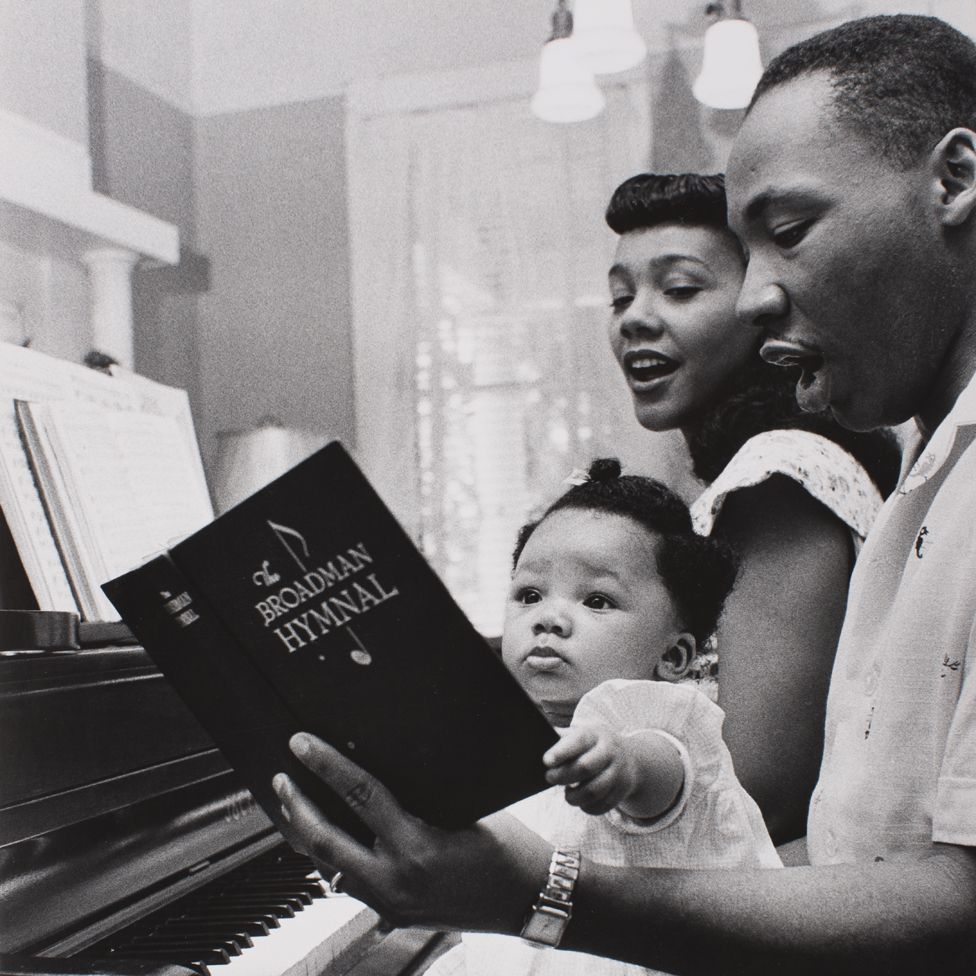

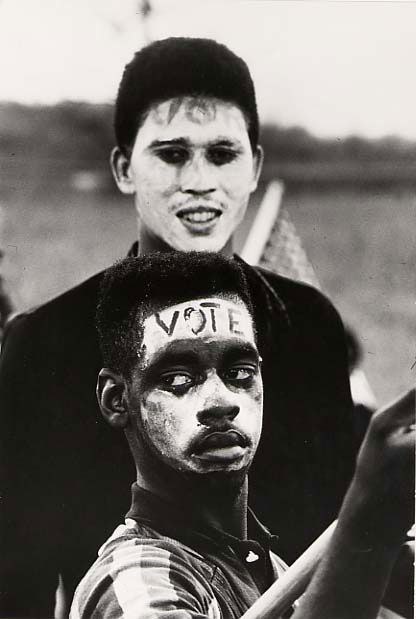

One of his assignments, given in 1955 by Johnson, was to cover Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The brotherhood between Sleet, Jr. and King grew into a lifelong bond. They had similar interests in common and were members of Sigma Pi Phi fraternity, the first, African-American, Greek-lettered organization. Activities that Sleet, Jr. recorded during their thirteen year kinship included the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955; the acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize by King, Jr. in 1964; and the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965. Because of their connection, Moneta Sleet, Jr. was even given access to the King family at their home.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

In “Moneta Sleet Jr., 70, Civil Rights Era Photographer, Dies” by Robert Mcg Thomas, Jr., published in The New York Times, the author wrote, “Known for his perpetual optimism, his ever-present smile and his knack for making others smile even when they didn’t feel like it, Mr. Sleet had such a gentle, engaging personality that he captivated the civil rights leaders and other Black celebrities he covered.” Upon inquiring how he was able to move beyond mastering the fundamental techniques of photography, Sleet Jr. responded, “You’ve got to know when to intrude and when not to intrude and when to pull back. You have to be very patient, a thing that’s good for me because I have a lot of patience and don’t mind waiting – the thing is to get the editors to wait.”

His commitment and emotional involvement allowed him to be a premier recorder of Black life. During the marches of the Civil Rights Movement, he had to walk twice as much, as Thomas, Jr. commented, “Mr. Sleet tended to march double-time, once estimating that he had walked 100 miles during the 50-mile march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965 because he kept walking back and forth along the line of march to take photographs.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

C. Gerald Fraser, also of The New York Times, referenced Sleet’s passionate but inobtrusive involvement in his article, “The Vision of Moneta Sleet in Show”. In their accompaniment with King, Jr. to receive his Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway, Fraser penned that Sleet, Jr. and Charles Sanders, a reporter for Jet, stated they had “…sort of really became adopted by the group. It’s kind of a peculiar position to be in because, on one hand, you are there as reporters and photographers, but people soon forgot that – and we had to be . . . discreet.”

Moneta Sleet, Jr. was so beloved and respected that many Blacks requested for him to be assigned to their story when covered by a Johnson publication. In fact, following the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Mrs. Coretta Scott King learned that there were no Black photographers covering the funeral of her husband. She immediately gave notice that there would be no photographers present at the service if Moneta Sleet, Jr. was not allowed in and given the best vantage point.

Moneta Sleet, Jr. photographed the funeral of King at Ebenezer Baptist Church, in Atlanta, Georgia, on April 9, 1968. From his position, he photographed the King’s youngest daughter, five-year-old Bernice, clutching her mother. Her disbelief and sorrow and Coretta’s quiet dignity and strength, captured on film, was so powerful and moving that the Associated Press transmitted Sleet’s photograph throughout the world.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1969, Moneta Sleet, Jr. was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for feature photography for this haunting photo of the Kings. His being awarded was a trifecta: he was the first Black man; the first Black person in journalism; and the first and only person working for a Black publication to win a Pulitzer Prize!

Although magazine journalism is ineligible for consideration for a Pulitzer Prize, his photograph qualified because of the international dissemination via the Associated Press. It should be emphasized that Moneta Sleet, Jr.’s attainment of professional success was rare for Black journalists; he had only worked with Black publications.

While many familiar and famous celebrities were photographed by Sleet, Jr., so were ordinary people, significantly children. He also captured images that detail history, including vestiges of segregation, that he wanted others to always remember. In “Moneta Sleet, Jr: Owensboro’s Pulitzer Prize Winning Photographer” by Danny May in Owensboro Living, his daughter, Lisa, recounted, “His subjects got all of his attention, no matter who it was” and even shared an account of her father not taking the phone call when the officials for the Pulitzer telephoned. In the middle of a photo shoot with actor and activist Harry Belafonte, he said he had to return their call when he completed his shoot. She praised, “He was that dedicated to his assignments.”

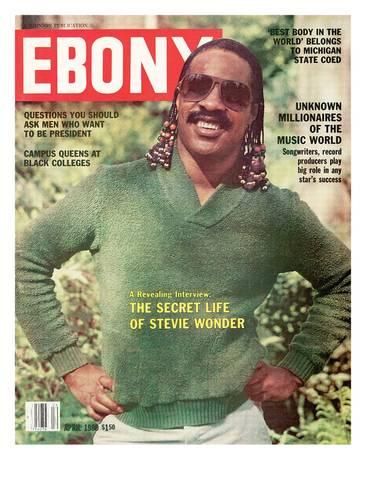

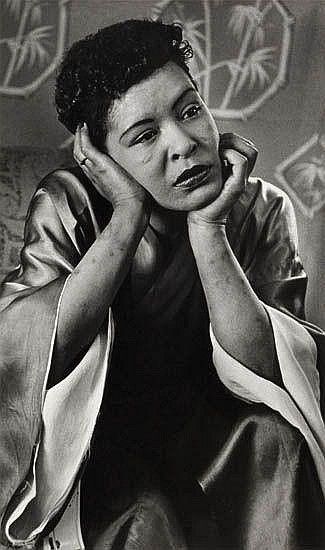

An exhibition of his work, The Vision of Moneta Sleet in Show, at the New York Public Library was presented to the public in 1986. The 125-photograph exhibition included, according to Fraser in The New York Times article of the same name, “… Betty Shabazz at the funeral of her husband, Malcolm X. Subjects in Mr. Sleet’s exhibition include his first professional assignment at the Harlem Hospital emergency room in 1951, independence celebrations in African nations, civil-rights marches in America, the homes and work places of celebrities, death row, beauty contests and visits to such places as a West Virginia mining town and Miami after a riot. … Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Liberia’s William Tubman, Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta, Adam Clayton Powell, Stevie Wonder at a recording session without his sunglasses, and a dejected, puffy-faced, needle-scarred Billie Holiday a year before she died – another of Mr. Sleet’s often-reproduced images.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

His work has also been featured in venues such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Studio Museum of Harlem, both of New York; the City Art Museum in St. Louis, Missouri and the Detroit Public Library in Michigan. His work earned him numerous awards from organizations, including the National Association of Black Journalists and the National Urban League, as well as accolades such as the Citation for Excellence from the Overseas Press Club of America. A bronze marker was erected at Max Rhoads Park on Seventh Street in his hometown, Owensboro, on February 24, 2000. The marker was in tribute to his immense contributions to journalism, significantly during the Civil Rights Movement, for more than four decades. This date was also declared “Moneta Sleet, Jr. Day”.

After returning to his home in Baldwin, Long Island, upon covering the 1996 Olympics, he was diagnosed with cancer. On September 30, 1996, Moneta Sleet, Jr passed away from cancer at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York City. As Thomas wrote in his New York Times article, Sleet, Jr. “…brought his camera to a revolution and ended up capturing many of the images that defined the struggle for racial equality in the United States and Africa.”

John H. Johnson dedicated a section of his publications to the work and memory of Moneta Sleet, Jr. In covering his funeral service in one of his magazines, Jet, Johnson saluted Sleet, Jr. as “a role model who influenced a generation of Black photographers.”

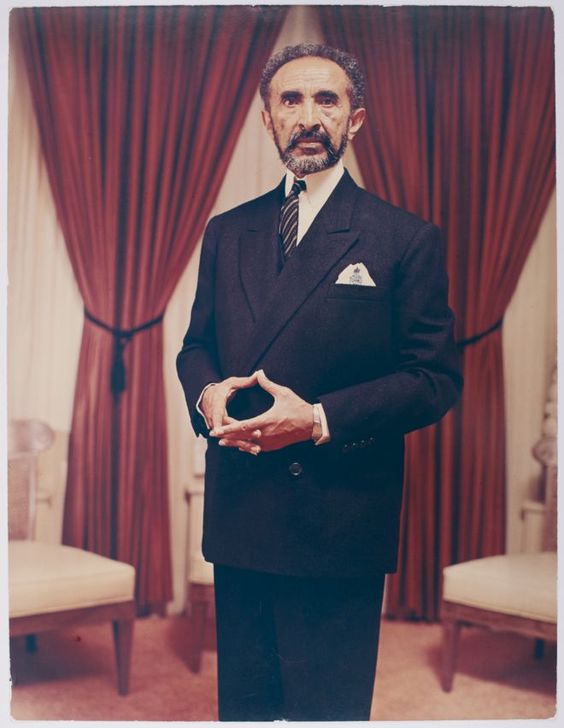

Also, in that tribute, the Executive Editor of Ebony, Lerone Bennett, Jr, championed, “He was a major witness, perhaps the greatest witness, of our greatest 50 years … He was there, he had a camera and an eye, and he saw it all: Haile Selassie in his doomed glory, Kwame Nkrumah at the beginning of the African Revolution; Adam Clayton Powell, Jr, Thurgood Marshall and Martin King at the beginning of the American Revolution, Fannie Lou Hamer in a Mississippi cottonfield, Rosa Parks on a Montgomery bus, Aretha Franklin demanding R-E-S-P-E-C-T. ‘Sleet’ was there. And in the end, the witness became the subject, the storyteller became the story, and the picture-taker became a picture and promise and a truth.” Bennett, Jr. and Sleet, Jr. had worked together for forty-one years and were good friends.

Echoing the sentiment of so many was legendary Black photographer Gordon Parks, who inspired Sleet. Parks composed a poem in honor of “Sleet”:

IN MEMORIAM (For Moneta Sleet)

You silence won’t separate you from us,

Nor from the hope you spawned—

Particularly during those

ungentle hours

when many Black hearts seemed

stripped of hope.

Best now that each of us attempt

to keep growing as you grew …

We owe you a fine remembrance, Moneta.

“I wasn’t there as an objective reporter … I had something to say and was trying to show one side of it. We didn’t have any problems finding the other side.”

~ Moneta Sleet, Jr.