“Her vision was much bigger than money … She didn’t want to sell this history away. What she wanted was for children to know what the accomplishments of African Americans were in this country, so she sacrificed her personal well-being to keep this collection alive here in the United States.”

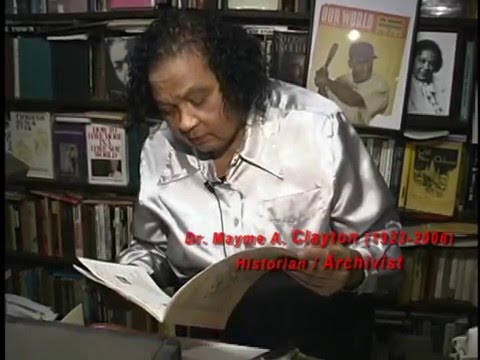

~ Lloyd Clayton, son & executive director, Mayme A. Clayton Museum & Library

On August 14, 1923, Mayme was born to Jerry Agnew, Sr. and Mary Dorothy Agnew (née Knight) in Van Buren, Arkansas. Her father, who successfully owned a general store, was the first African-American business owner in their city; this accomplishment brought immense pride to the Agnew family. Her mother, who was a homemaker, was renowned for her cooking and especially her dinner parties.

In 1932, when Mayme was nine years old, she and her classmates visited the library in her all-Black school. She saw that none of the books were about skilled and talented Black people; however, she knew that they existed, just from looking at her parents. She felt that African-Americans were purposely being omitted and that she had to work to preserve the history of African-Americans, lest it all be forgotten or erased. In a reflection that her youngest son, Lloyd relayed in “Preserving African-American Legacy: Mayme A. Clayton” by Ramy Eletreby, he shared that her experience in the school library was an epiphanous moment that led to her mission in life. He affirmed, “My mother was a very spiritual person … She was raised Southern Baptist and because of that, she always felt that she had some higher purpose to fulfill.”

Her parents were supportive of her intent, as they were resolute in exposing her and her two siblings, Sarah and Jerry, Jr., to the many and diverse achievements of African-Americans. One of these African-Americans was Mary McLeod Bethune, founder of a historically Black institution of higher learning, Bethune Cookman University, as it is presently known. In 1936, Jerry, Sr. took their family to hear the famed educator and activist speak. That experience would inspire Mayme throughout her life.

After graduating from high school, at only sixteen years old, Mayme Agnew briefly attended Lincoln University, a historically Black university in Jefferson City, Missouri. In 1944, she moved to New York and gained work as a photographer’s assistant and model. While working there, she met Andrew Lee Clayton, a barber and soldier. Clayton, who was sixteen years her senior, began to court her; after ten months, they were married in 1946.

The Claytons relocated to the West Adams community in Los Angeles, California. They would rear their three sons, Avery, Renai and Lloyd, to be knowledgeable in and proud of their cultural heritage.

In 1952, Mayme Clayton was hired as a librarian’s assistant at the University of Southern California (USC). Seven years later, she accepted a position to work in the law library at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). When the Afro-American Studies Center Library was created by UCLA in 1969, Clayton, as a consultant, began building the library’s collection. She had been selected because she had become well-known for her expertise and her collection of Afro-American literature. It proved to not be the experience that Clayton hoped, as the university was primarily interested in contemporary works and refused to purchase that were rare or out-of-print.

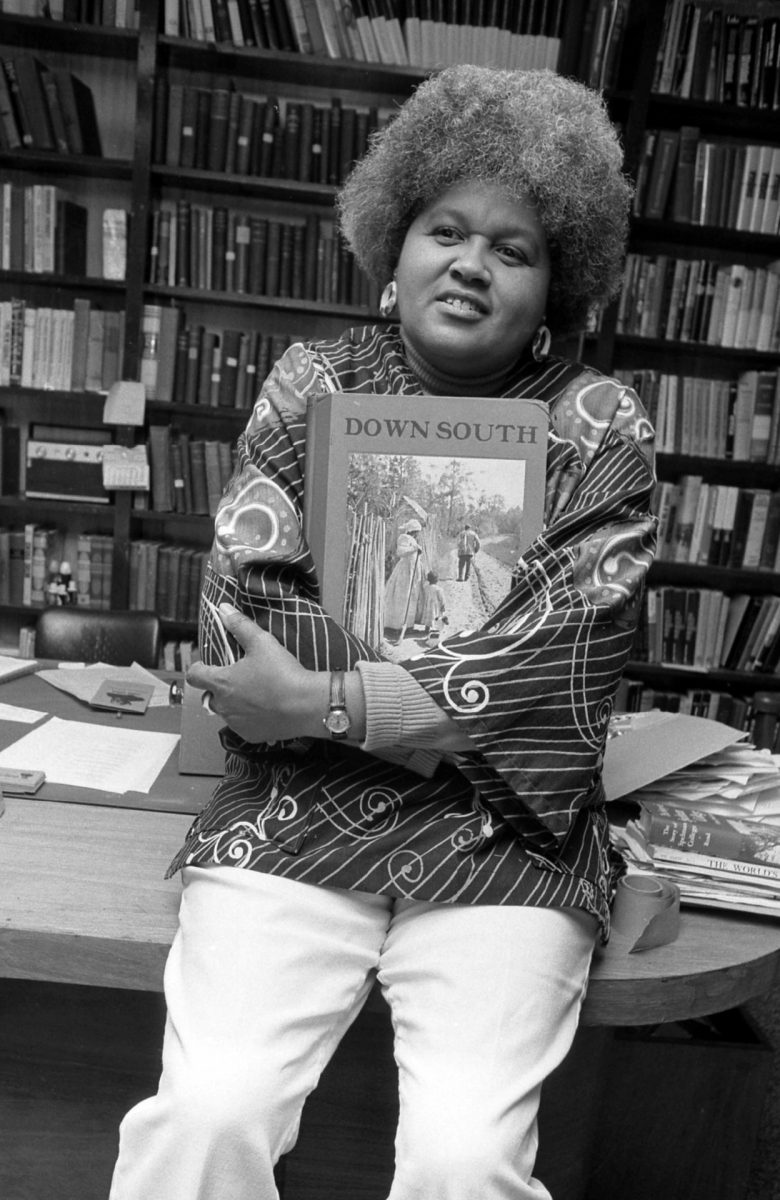

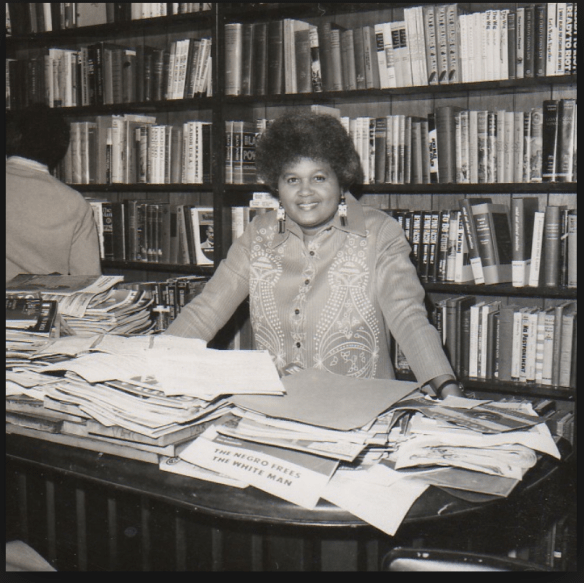

Mayme Clayton continued being proactive about preserving and educating others on Black culture and began acquiring more cultural capital. She became well-known among collectors and scholars of Black history and her expertise, especially in materials of the Harlem Renaissance and Black cinema, grew profoundly. For more than four decades, Clayton scoured antique and second-hand stores, bookstores, flea markets, estate auctions, garage sales and even discarded materials sites for her ever-expanding cache. These materials were stored in her West Adams bungalow home and spilled into her garage, completely taking it over. She was able to secure items by living modestly and, from time to time, selling particular items.

Clayton was highly skilled at bargaining in order to gain the best value for her purchases. In the New York Times article, “Black History Trove, a Life’s Work, Seeks Museum”, written by Jennifer Steinhauer, the curator of African- American collections at Emory University, Randall K. Burkett recalled, “I distinctly remember trading four items I had, which included a signed poem by Langston Hughes, for one book … let’s just say she did very well.”

Another account included her son, Lloyd, discussing how Mayme bought the first edition of the first issue of Ebony. Ebony, an African-American news & lifestyle magazine, was first published in 1945 by Johnson Publishing Company of Chicago, Illinois. This issue was part of a collection of magazines that was donated to the Claytons by a private household in Los Angeles. The downside was that the magazines had been stored in a garage that had been soaked with the weekend’s rains. They were able to rescue many of the items, including the premier issue of Ebony, from water damage. In the 2019 “The Mayme A. Clayton Library & Museum and Its 25, 000 Artifacts of African-American History Face Eviction from Culver City”, authored by Colin Newton for The Argonaut, Lloyd, regaled, “My mother would never show any excitement. She was there just to observe and collect …when we got home, wow, did she explode … We have that and we keep that.” In fact, Mayme Clayton refused to lend it back to John H. Johnson, the publisher!

An avid golfer, she also organized and sponsored the Mayme A. Clayton Celebrity Golf Tournaments, in which a portion of her proceeds were allotted to support her extensive collection and procurement of new materials. Celebrities who supported her efforts include actor Glynn Turman, who said in a 2006 Los Angeles Sentinel, that Clayton showed “such a zest for life and a profound interest in many things and knew so much. Talking with her was like listening to a sage who really knew everything. She had the heartbeat of the community and it was never about her. It was always about the other person.” In her travels playing golf, she sought new finds for her collection.

At this point, she and her husband, Andrew, separated because he did not want her to work as much. Mayme Clayton continued to grow in her vision. She began to add photographs, legal documents such as bills of sale of enslaved Africans and plantation inventories, newspapers, Black film posters and other ephemera to her collection. In 1972, she retired early from UCLA and visited West Africa. Her time there would be educational, inspiring her to add African works to her items of interest; she would later add Indigenous American and Chicano materials.

Upon her return, she began to work at Universal Books, a store that dealt in used books and contained a massive selection of Black literature. The owner had heard of her and her collection, allowing her to bring it in his store. She soon become a co-owner of the bookstore, investing much of her retirement resources into Universal Books. Unbeknownst to her, her business partner had gambling issues. Soon after becoming partners, he lost all of the business’s profits in one day, forcing the closing of the bookstore. Instead of suing him, she conceded to take possession of his share of the store’s inventory centered upon Black culture, more than 4, 000 volumes total. All the store’s inventory was moved to her home and there, she opened her own store, Third World Ethnic Books.

During this time, Mayme Clayton returned to school to resume her formal education. In 1974, she earned her Bachelor of Arts degree in History from the University of California, Berkeley; in 1975, she earned her Master of Arts degree in Library Science from Goddard College; and in 1983, she was awarded her Doctoral degree in Humanities from Sierra University.

Her formal education supported her personal and professional growth. In 1972, she founded the Western States Black Research and Education Center (WSBREC) in order that, according to her interview on the documetary series, The History Makers, “ … children would know tht Black people have done great things.” The WSBREC contained the largest private collection of African-American historical materials in the world. According to the Steinhauer article, Clayton’s collection included, “…first editions by Langston Hughes and nearly every other writer from the Harlem Renaissance, many of them signed; a rare biography of the architect Paul R. Williams (see ISSUE #2); and the oeuvre of the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. There is an edition of “The Negro’s Complaint,” a poem, complete with hand-painted illustrations; books by and about every notable American of African descent from George Washington Carver to Bill Cosby; and thousands more items concerning those whose names were lost or never known.” The WSBREC provided programming, including community outreach, for greater than four decades. Clayton served as its executive director and as president when her son, Avery, acted as the executive director. Alex Haley, journalist and author, notably of Roots, served as the national board chairman.

She first met Alex Haley in the early 1970s when he visited her, seeking material for his genealogical research. They continued to do business, discussing the incredible importance of Black culture, before he left the States. Haley visited West Africa, continuing his search for his ancestry. In 1976, his groundbreaking historic novel, Roots was released. In the Argonaut article, it stated that Haley “expressed his gratitude for the library by donating an autographed first edition of Roots. The Jan. 16, 1977, dedication reads: “Mayme Clayton, my sister. The very warmest best wishes to you and your family from the family of Kunta Kinte!”

The collection of Mayme Clayton is considered, according to UCLA Magazine, to be “one of the most important collections of African-American materials and consists of 3.5 million items”. It includes more than 75, 000 photographs, almost 10, 000 sound recordings and 30,000 out-of-print, rare and first edition books by and about Blacks. These books include those by Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes and Richard Wright; and a complete set of The African Repository, the first abolitionist journal in the United States (1830-1845). However, its most valuable piece is the only known signed copy of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. Composed by Phillis Wheatley in 1773, it is the first book of poetry published by an African American woman in the United States.

The Clayton collection also has personal correspondences of Black entertainers and leaders such as those of Booker T. Washington to George Washington Carver when they led, in administration and agricultural sciences, respectively, Tuskegee University. It even contains sheet music and music scores to films. Her private collection, which ranks with the public collection of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, is exceptional because of its extraordinary amount of depth and range. It has drawn great admiration from historians, scholars and collectors, such as Phillip J. Merrill, an expert on African-American memorabilia, to exclaim in the New York Times article, “A collection like this is, in my mind, priceless.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Her interest in Black films prompted her to create the Black American Cinema Society (BACS), which housed the Clayton Library Film Archives. Holding greater than 1,700 titles and more than 350 film posters, the archives was the largest collection of Black films, released before 1959, in the world. It housed the largest, worldwide, collection of 16mm films made by Blacks, including those of Oscar Micheaux (see ISSUE #4). The “Father of “Black Cinema”, Micheaux was an author and the first major African-American filmmaker. A producer of “race”, i.e. Black, films, he was the most successful African-American filmmaker of the first half of the 20th century.

Building on her interests in Black film, in 1977, Mayme Clayton created the first public Black film festival in the United States: The Black Talkies on Parade (BTOP) Film Festival. Held at the Los Angeles Museum of Science and Industry, it featured films from her collection. Clayton, collaborating with BTOP, also initiated the annual Black Student and Independent Filmmakers Competition. In 1993, she contributed more than $50,000 in cash grants to award Black filmmakers. Clayton taught African-American Cinema at California State University. She also worked on Black programming for network and cable television.

In 1995, her expansive film collection was transitioned to a warehouse of Eastman Kodak, the premier photography technology company in the United States. At the company’s warehouse, her films have been stored in a climate-controlled vault. Her efforts led her to learn about film preservation; she even starred in Keepers of the Frame, a 1999 video that promoted film preservation as a means of record to better understand the 20th century.

In 1999, she co-founded of the annual Reel Black Cowboy Film and Western Festival held at the Gene Autry Museum in Los Angeles. The purpose for this was to let others know the great impact that Blacks, from cowboys to medical professionals, had in settling the American West (see ISSUE #3). Even though her health had begun to fail, she continued to work on her mission. Her son, Avery, remarked in the Washington Post that his mother had bought an original film poster for The Bronze Buckaroo, which starred Black singer, Herb Jeffries,for $1,000 just a few months before she passed.

Throughout the years, a goal of Mayme Clayton was to attain a permanent home for her incredible collection. Aspects of the collection were distributed between her home and accompanying onsite property and storage units throughout Los Angeles. She was fearful that the elements and dangers, such as mold, would cause immeasurable damage. In the Los Angeles Sentinel article, it stated that Los Angeles County Supervisor Yvonne Burke had been highly concerned about the security of her collection, as she had no insurance and only had a dog to stave off any burglaries. Clayton responded, “In my neighborhood, they do not steal books.”

Suffering from pancreatic cancer, Mayme and her sons worked diligently to try to secure an institution that would be able to showcase her collection, with the condition that it be made available to the public. On October 11, 2006, Culver City agreed to lease a 22,000 square foot facility to the WSBREC for $1 per year.

The next day, October 12, 2006, Mayme Agnew Clayton passed away. Her life and vision were celebrated at the Agape International Spiritual Center in Culver City with over 800 guests in attendance.

In February 2007, movers, specialized in handling rare materials, began transporting items from Clayton’s properties to the new WSBREC facility, a former courthouse. Universities loaned out staff members in order to assist and organize what would be called the “Mayme A. Clayton Collection of African American History and Culture”. It would be divided into five separate collections, including music, which her son, Lloyd, would administer, and sports, which her son, Renai, would oversee.

The recipient of numerous awards, including the Iota Phi Lambda “Woman of the Year” Award, the Rosa Parks Award and the Paul Robeson Award, Mayme Clayton also received many accolades, such as being named one of the “Top 100 Collectors Who Are Making a Difference.” In tribute to her, the WSBREC would be renamed the “Mayme A. Clayton Library & Museum” in 2007.

However, her influence and dedication cannot be measured. In a 2007 Los Angeles Times article, Sara S. Hodson, curator of literary manuscripts for the Huntington Library, declared about Mayme Clayton and her collection, “A lot of it is material that might not have been preserved if Mayme Clayton had not gone after it, as single-minded and devoted as she was … There is no doubt that this is one of the most important collections in the United States for African-American materials; it is a tremendous resource for all Americans, but especially African-Americans, whose history has largely been neglected.”

“I always had a desire to want to know more about my people …. It just snowballed, it just kept going. I have invested every dime that I have, everything that I have, in books for future generations. It may change somebody’s life – you can never tell.”

~ Mayme Agnew Clayton