The Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, comprised of six buildings, is located at East Leigh Street and North 2nd Street in Richmond, Virginia. Situated in the historic Jackson Ward neighborhood, it, according to the National Park Service (NPS) website, is a community “… known as the birthplace of African-American entrepreneurship (‘The Cradle of Black Capitalism’) and is one of the largest (42 city blocks) national historic landmark districts associated with African American history and culture in the United States.” As such, the facades of all the buildings have been preserved, rehabilitated and/or renovated to appearances of the 1930s era.

Maintained by the National Park Service, five of these buildings house operations of the federal agency. Their operations include curatorial spaces and a Visitors Center. The interiors in these buildings have been modernized to meet their professional needs and engage the interests of the contemporary public.

The gem of this site is the two-story, Italianate brick home of entrepreneur Maggie Lena Walker (1864-1934). Creating and leading the Saint Luke Penny Savings Bank in 1903, Walker became the first African-American woman to both charter a bank as well as serve as a bank president in the United States!

As the Right Worthy Grand Secretary (1899-1934) of the Independent Order of Saint Luke, its highest position, Maggie L. Walker devised diverse plans to further develop the organization to prosperity. She envisioned a conglomerate that allowed for the creation of their own newspaper, bank and department store in order to progress the Black community. With these three enterprises, the Black community would have greater possibilities of becoming independent, economically, socially and progressively, for years to come.

Within five years of her sharing her plans in 1901, Walker led the manifestation of all three into existence. In 1902, the St. Luke Herald began being published; its purpose was to share the work and accomplishments of the Order and assist in their efforts of education.

The Saint Luke Penny Savings Bank (1903) was managed and maintained by members of the Independent Order of Saint Luke. Founded in 1869, it was an African-American fraternal society devoted to the progress, via economics and culture, of the Black community. It also promoted cooperation, unity and self-help as well as assisted those in need, including children, the infirmed and elderly. Walker joined the Order in 1881 when she, seventeen-years old, was enrolled at the Richmond Colored Normal School.

Highly engaged during her involvement within the Order, Walker was innovative and creative. Committed, Encyclopedia Virginia reported that “she devoted the rest of her life to building membership and resources, expanding activities in business and social service, and keeping the financial operations efficient. Under Walker’s guidance, the Independent Order of Saint Luke’s fortunes were completely reversed. Although she inherited the Order deep in deficit, over the twenty-five years of her leadership it collected nearly $3,500,000, claimed 100,000 members in twenty-four states, and built up almost $100,000 in reserve.”

In 1905, the Saint Luke Emporium opened its doors. It provided employment to African-Americans, especially women, and access to quality goods at affordable prices. Championing the respect that should be afforded Black consumers, Walker refused to shop where Blacks were told to use the back and side doors or be forced to wait after Whites in order to be serviced. Unfortunately, White retailers’ backlash and some Blacks’ fear of retaliation for shopping at the Order’s store ultimately led to the Emporium closing in 1911.

The lifelong commitment of Maggie L. Walker to attain gender and racial equality via community service, economics, education, entrepreneurship and social mobility has garnered many honors, including preservation of her family home located at 110 ½ East Leigh Street.

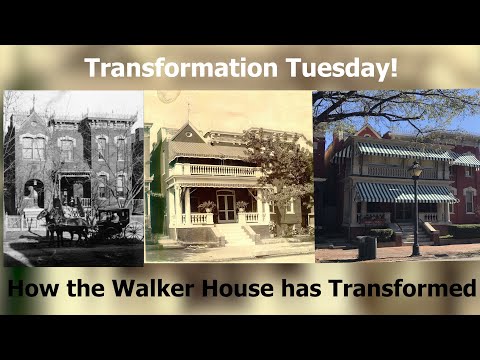

The Walker family moved to this house in 1904. The house was constructed in 1883 by African-American architect George Boyd, who had been formerly enslaved. He designed the home at 110 ½ East Leigh Street in an Italianate style that included, as per the National Park Service, a “low angled roof and highly decorated overhanging eaves … tall narrow windows on the front of the house … heavily accentuated vertical structures and also utilized window sashes .. porch … and the columns, both located outside and inside the home, evoke the memory of the Italian Renaissance. The interiors of the Italianate style were less defined than the exteriors, however, there were some notable ideas present in the Walker home. One of them is that most of the rooms will have multiple entrances and exits, and this is very evident in the Walker home with most rooms having three doorways, even the bedrooms, which all connect to each other and to the hallway.”

Prior to their moving in, two major upgrades were made. The Walkers had electricity as well as a central heating system, including a basement furnace, installed. The lighting in the house had been powered for gas usage. According to the NPS, it was decided that “instead of replacing all the light features, they were retrofit to be electric powered, keeping the old gas aesthetic with the function of electricity.”

Once ready, the Walkers settled into their home. The Walker family included husband-and-wife Armstead and Maggie; their two sons, Russell Eccles Talmadge and Melvin DeWitt; their adopted daughter, Margaret “Polly” Anderson; and Maggie’s mother, Elizabeth Mitchell. Their infant son, Armstead Mitchell, passed away at only seven months old.

Over the next twenty years, the home was modernized. Additions, including a sleeping porch, laundry, bathrooms, bedrooms and a den to entertain guests, were made to accommodate the growing Walker family, as all three children married. By 1924, the Walker family included Armstead and Maggie’s four grandchildren, who also resided in the house. The home of the Armstead and Maggie L. Walker family would expand, growing from its original nine rooms to a staggering twenty-eight!

In 1928, an elevator was installed in the rear of the Walker home. It was designed by Charles T. Russell, the first African-American architect in Richmond, Virginia. He had previously completed work on several buildings of the Independent Order of Saint Luke. Suffering diabetes, Maggie was experiencing great difficulties walking, especially the stairs of the home. Although she used leg braces, Walker could not prevent her forthcoming paralysis. Fortunately, she was able to remain in her home until her death.

On December 15, 1934, Maggie L. Walker passed away due to diabetic gangrene; she was seventy years old. Tragically, in 1915, her husband, Armstead, was accidently shot and killed by their son, Russell; they were looking for an intruder in their home. Arrested for murder, he was found innocent. Yet Russell never recovered from the accident and after suffering alcoholism and depression for eight years, he died in 1923.

This left the home to be in care of her son, Melvin. Sadly, he passed away in 1935. His widow, Harriet “Hattie” Naomi Frazier, became the owner and lived there with their daughter, Maggie Laura Walker, and her sister-in-law, Polly. Greatly inspired by her mother-in-law, she also served as the Right Worthy Grand Secretary of the Independent Order of Saint Luke. She also wanted to preserve and promote the rich legacy of Maggie L. Walker. As such, Hattie diligently kept their family home in the manner that Maggie would have wanted. She hoped for it to one day be converted into a museum. Her active preservation for more than thirty years proved to be worthwhile. Although she died in 1974, Hattie Walker’s hope manifested through her daughter, Maggie.

In 1975, the home of Maggie L. Walker was added to the Virginia Landmarks Register and the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as well as designated a U.S. National Historic Landmark. The following year, it was designated as a U.S. National Historic Landmark District Contributing Property. In 1978, the home was designated a U.S. National Historic Site. In 1979, the U.S. National Park Service bought the Walker home from Maggie L. Walker, the granddaughter of Maggie L. Walker.

After restoration and renovation, the NPS made it available, as a museum, to the public in 1985. Its design and décor remain true to how it looked when the Walker family dwelled there and includes their original items.