On April 26, 2018, The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration opened to the public. Located at 115 Coosa Street in downtown Montgomery, Alabama, it is a counterpoint to The National Museum of Peace and Justice, which also opened the same day and is situated mere feet away at 417 Caroline Street.

Historically and presently in America, there has been an inordinate amount of marginalization and discrimination exhibited towards persons of color. Prompted by the absence of domestic responsibility and restitution, lack of racial equality and dearth of social and economic justice, the Equal Justice Initiative began conducting research over ten years ago. It delved into the history of racial injustice and the complex systems that have allowed this travesty to proliferate. Intent on attaining equal justice for all, the product of their research is The Legacy Museum.

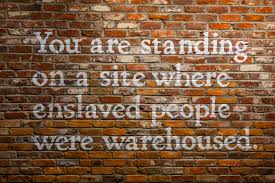

The 11,000 square foot museum was constructed at a former warehouse site where enslaved Blacks were imprisoned. It is positioned between a historic slave mart and a main river dock, where tens of thousands of Black people were sold into slavery. The selection of its location and proximity to Montgomery, as stated on their site, is in “ … the fertile Black Belt region, where slave-owners amassed large enslaved populations to work the rich soil, elevated Montgomery’s prominence in domestic trafficking, and by 1860, Montgomery was the capital of the domestic slave trade in Alabama, one of the two largest slave-owning states in America.”

The Legacy Museum and the National Museum for Peace and Justice were constructed on six acres of land. Both institutions were developed from the research and outreach by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a non-profit organization based in Montgomery, Alabama. Founded by MacArthur Fellow Bryan Stevenson, J.D., in 1989, the EJI offers legal representation to those who may not be able to afford quality representation, have been denied a fair trial or have been wrongly convicted. The organization also guarantees the defense of any person in Alabama who is facing the death penalty. Stevenson, a successful attorney, activist and critically-acclaimed author, he is perhaps most popularly-known for his 2014 book and the 2019 film on which it was based, No Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption.

The concepts for this memorial and museum were birthed in 2010, when the EJI began investigating the thousands of lynchings of Blacks and accompanying domestic terror unleashed on Black communities in the American South. While many of these attacks were undocumented, more than six million Black people would flee the region for safety, their emigration giving rise to The Great Migration.

The research of the EJI led to the 2015 publication of Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, which detailed racially-terroristic lynchings in twelve states. Post-publication, the EJI continued to research lynching across the United States. Their research led them to visit hundreds of sites, gather data, conduct interviews, collect soil and post markers, “in an effort to reshape the cultural landscape with monuments and memorials that more truthfully and accurately reflect our history.” In all, researchers have documented more than 4, 400 racial terror lynchings that occurred between 1877 and 1950, many of which occurred prior to and just after the beginning of the 20th century.

Stevenson was compelled to create this museum and memorial to honor those persons victimized by a crippled, corrupt criminal justice system and domestic White terrorism. The $20 million complex, utilizing design and sculpture, features a memorial square built in collaboration with MASS Design Group. This non-profit firm has worked in environments, such as Rwanda, that suffered mass trauma and pursued justice and reconciliation. The funds supporting the development of these two institutions were raised from charitable foundations and private donations.

The diverse media and works within The Legacy Museum are to be viewed in chronological order so a greater understanding of the past may be gained for a more equitable future. By examining life depicted, from Africa before the Triangular Slave Trade to contemporary experiences of Blacks surviving inequitable conditions within the United States, the museum wants visitors to compare, contrast and connect the multitude of macro- and micro-aggressions that have persisted from the past to the present. Primary documents, archival materials, artifacts and memorabilia, oral histories and technology are just several of the ways that the museum engages guests. Artists, such as Elizabeth Catlett, Jacob Lawrence, Sanford Biggers and Hank Willis Thomas, provide visual works that detail topics such as auction of humans for slavery, racial terror lynching, Black oppression, legal and illegal segregation, racial profiling and mass incarceration of minorities into the prison industrial complex.

Since its opening, tens of thousands of visitors have already visited the memorial and museum. The premier of The Legacy Museum and The National Memorial for Peace and Justice catapulted Montgomery to be placed as one of the world’s 52 Top Tour Destinations for 2018 by The New York Times.

The EJI has been engaging with numerous organizations within dozens of communities who are working to be more equitable and just to those they have historically discriminated against and marginalized. One of these communities is Montgomery and an organization is the Montgomery Advertiser. Prompted by the work of the EJI, its publishers reviewed its historic coverage of lynchings, which all too often was highly inflammatory against Black victims. The publication admitted their shame, accepted culpability for their transgressions and issued a formal apology.

The involvement of Montgomery to rectify its wrongs and work towards enhanced equity for all is monumental, especially considering the horrific and tragic past of slavery and legacy of racism and discrimination. Though this movement spurred by Stevenson and the EJI has opposition, as the mayor of Montgomery, Todd Strange, expressed “… these may be the greatest opportunity for America to reconcile with its truth.”