“… a legend, an icon and an inspiration. It is impossible to overstate what she meant to our city and to our community. At Dooky Chase’s Restaurant, she made Creole cuisine the cultural force that it is today, she made a family-owned sandwich shop into one of the first African-American fine dining restaurants in the country, and she made history – with Dooky’s serving as a cradle and a hot spot for the civil rights movement.”

~ LaToya Cantrell, mayor of New Orleans

On January 6, 1923 in New Orleans, Louisiana, Charles and Hortensia Lange welcomed into their lives a baby girl; she was named Leyah. The Lange couple was Creole, comprised of African, French and Spanish descent. There are various sources that report different numbers of siblings and her birth order but according to the African American Chefs Hall of Fame, she was the oldest of fourteen children. Also, the spelling of her name at some point is abbreviated from Leyah to “Leah”.

Charles was a caulker for different shipyards and Hortensia was a homemaker. When Leah was very young, the Lange family moved to Madisonville, a small town situated on the Tchefuncte River. Known for shipping and constructing boats, it was an opportunity for Charles to gain greater opportunities for employment.

The Great Depression occurred when Leah was just six years old. Although life was challenging at times, it was especially true during this period. Charles gained employment, earning fifty cents per day, from the Works Progress Administration. In “Leah Chase, ‘A Legend’ Whose Restaurant Dooky Chase’s Helped Change New Orleans, Dies at 96” written by Ian McNulty that was featured at NOLA.com, Leah reminisced, “Father told us to pray for work every day … We’d go fishing in the mornings so we could have perch and grits for breakfast, but a lot of times, man, it was just grits.”

Growing up in Madisonville, she was reared on land her family owned. At an early age, Leah and her siblings assisted the adults in cultivating crops, which included greens, okra and strawberries. Being able to live off what they grew was indeed a blessing that would always impact Leah.

The Lange practiced Catholicism but when it was time for Leah to attend high school, there were no secondary schools for Blacks. At thirteen, she moved to live with her aunt in New Orleans, where she matriculated St. Mary’s Academy, a Catholic school for Black girls. After graduating at sixteen years old, she returned to Madisonville. However, she left for The Crescent City, which, as of 1941, became her permanent home.

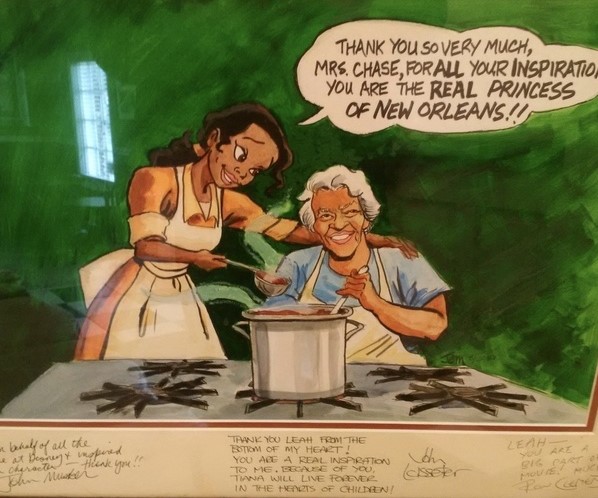

(No copyright infringement intended).

In New Orleans, Leah Lange worked a variety of jobs to support herself. With the onset of World War II, many women were able to attain work that had recently become vacant due to the enlistment of men. According to the website of the National Visionary Leadership Project, she “had a colorful work history including managing two amateur boxers and becoming the first woman to mark the racehorse board for a local bookie.

Her favorite job, though, was waiting tables in the French Quarter. It was here that she developed her love for food and feeding others.” Her work at the Colonial Restaurant and The Coffee Pot eatery was perfect training for her next life step. In the McNulty article, Leah exclaimed, “I saw just how wonderful the restaurant business was, how you could sit down and enjoy a meal and have someone serve you … Oh, I thought, that was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen.”

This next step would permanently enhance her life. In 1946, she married Edgar “Dooky” Chase, Jr., a band leader and jazz trumpeter prominently known throughout New Orleans. They would be blessed with four children.

During the 1950s, Leah began working with her in-laws. In 1941, Edgar “Dooky” Chase, Sr. and Emily Chase (née Tenette) opened the doors of its eatery in the Tremé community. Located on a corner of Orleans Avenue and North Miro Street, the elder Chase couple sold lottery tickets and sold homemade po’boy sandwiches.

As time passed, Dooky Jr. and Leah assumed proprietorship. They, ultimately, converted it from being a tavern built in a double shotgun building to a sit-down establishment and called it “Dooky Chase’s Restaurant”. Leah incorporated her own family’s Creole dishes as well as those often served in upscale eateries that barred Blacks. The delicious fare and welcoming atmosphere at Dooky Chase’s Restaurant soon endeared it to many, prompting it to become a favorite place to dine in New Orleans.

(No copyright infringement intended).

By the time of the Civil Rights Movement, Dooky Chase, as it was called for short, became more significant than simply a dining destination. An institution for the New Orleans Black community, it became one of the few places in the city where African Americans could discuss political business and organization. This business involved activities such as strategy meetings and voter registration.

The Chase couple hosted and fed everyday citizens; members of organizations like The Freedom Riders and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); and civic figures including Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and New Orleans’ own Alexander Pierre “A.P.” Tureaud and Ernest “Dutch” Morial.

Tureaud served as the attorney for the New Orleans chapter of the NAACP. His lawsuit, aided by attorneys Robert Carter and (future U.S. Supreme Court Justice) Thurgood Marshall, led to both the end of segregation in New Orleans and integration of elementary schools in the Deep South. His lawsuit for desegregation against Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge led to his son, A.P. Tureaud, Jr. being the first African-American to attend the university.

Morial was a man of several firsts: he was the first African-American to receive a law degree from Louisiana State University (1954); the first Black member in the Louisiana State Legislature since Reconstruction (1967); the first Black Juvenile Court judge in Louisiana (1970) and the first Black elected to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals (1974) and the first (and only) African-American of the inaugural class to be inducted into the Louisiana Political Museum and Hall of Fame (1993).

Because of the nature of these meetings, they were clandestine. Held in the dining room on the second floor at Dooky Chase, Leah Chase served her signature gumbo and friend chicken to the activists. It was here in the later years of the Movement that King, Jr. and others learned more about bus boycotts due to success of the Baton Rouge Boycott in 1953. The Louisiana boycott would inspire the Montgomery bus boycott.

Though officials knew of these private gatherings, the Chase couple was not sanctioned. Their importance is affirmed by African-American civil rights activist and author Rudy Lombard. A native of New Orleans, he coordinated and led one of the first sit-ins at a Canal Street lunch counter. Lombard, as per the NOLA.com article, advised, “If you’re looking for a place that advanced integration and racial understanding, nothing stands out for me more than that restaurant and that lady … It was the only place where people knew Blacks and Whites could get together in a civil rights context without being hassled … (The police) knew what was going on; they were following us – but nothing ever happened to us there.”

In that same article, McNulty cited Maurice “Moon” Landrieu, the 56th mayor of New Orleans who was succeeded by Morial. Landrieu, an integrationist who later acted as the 7th United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under President Jimmy Carter, discussed, “It took a long time for the law to be followed and for customs to change, but people found it welcoming to eat together at Dooky Chase … If you reversed the situation and think about Black people going to a White restaurant at that time, well, it was one thing then to say you have the right and it was another to say you felt comfortable. But at Leah’s place, you wanted to be there because of the food, the hospitality and just her personality.”

The Chase family did receive threatening letters and at one point, a pipe bomb destroyed part of the building. However, it is believed they and their establishment remained able to operate due to the New Orleans community not wanting any negative backlash over its beloved Dooky Chase.

Also adding to their great significance was that the Chase family honored the checks of many Blacks because there were no Black-owned banks in their communities. A majority of them worked blue-collar professions alongside the Mississippi River and found it practically impossible to be treated ethically by White financial institutions. At Dooky Chase, they were treated with dignity, could dine and enjoy culture, which included live musical performances and beautiful art.

Many famous people also felt at home at Dooky Chase’s Restaurant. These diners include Hank Aaron, James Baldwin, Beyoncé and Jay-Z, Bill and Camille Cosby, Keith David, Duke Ellington, Ernest Gaines, Lena Horne and President George W. Bush and President Barack H. Obama. Ray Charles, a red beans and rice fan, even sang about the restaurant in “Early Morning Blues”. He crooned, “I went to Dooky Chase’s to get something to eat/The waitress looked at me and said, ‘Ray, you sure look beat.’”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Perhaps one of the most unexpected gifts Leah Chase made possible was the support of Black artists and promotion of Black art. Because of segregation, she was unable to visit an art museum until she was fifty-four years old. Her visit occurred with her good friend, Celestine Cook, who became the first African-American to be a board member of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

A lover of the arts, Chase’s advocation was expressed in her outreach. This included her serving on the board at the Museum of Art as well as the boards of Arts Council of New Orleans, the Greater New Orleans Foundation, the Louisiana Children’s Museum and the Urban League of Greater New Orleans. She catered gallery openings for upcoming and established artists; collected art created by African-American artists such as Ron Bechet, John T. Biggers, Elizabeth Catlett, David Driskell, Lois Mailou Jones, Chase Kamata, Jacob Lawrence, Samella Lewis, Sue Jane Mitchell Smock, Mose Tolliver and Clifton Webb; and displayed her beautiful pieces inside Dooky Chase. Musicians were also welcome to perform in the family restaurant.

She had even traveled to Washington, D.C. to speak before Congress in support of the National Endowment for the Arts. There, Leah Chase, according to the African-American Chefs Hall of Fame site, emphasized that the arts are “an investment in the education of the neighborhood. Kids need to see something beautiful and breathtaking in order to aspire to higher things and value living more.”

In between her work and activities, Leah Chase authored three books, sharing her cooking with loyal fans and the new converts. These books were The Dooky Chase Cookbook (1990), Down Home Healthy: Family Recipes of Black American Chefs (1994) and And Still I Cook (2003). Well-received when published, their popularity has grown even more over the years.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans and the Chase restaurant was not exempt. Fortunately, a grandson was able to save all the artwork, later storing it for preservation. For a year, Leah and Dooky lived in his-and-hers trailers across the street from their establishment. In 2006, a fundraiser garnered more than $40,000 to assist in rebuilding and renovating Dooky Chase’s Restaurant. Always concerned about her community, Leah Chase was also a member of Women of the Storm, a coalition who lobbied Congress to greater assist in the restoration of New Orleans after Katrina and Hurricane Rita.

In 2007, Dooky Chase’s Restaurant opened its doors again and installed inside was her treasured art collection. Leah Chase continued to work at Dooky Chase when many people would probably have retired a couple times. In the early morning, she could be found preparing food to be cooked for the day and when her health did not allow her to spend the long hours the establishment demanded, she still oversaw the operations.

In 2013, the Chase couple also developed the Edgar L. “Dooky” Jr. and Leah Chase Family Foundation whose mission, according to their website, is to “cultivate and support historically disenfranchised organizations by making significant contributions to education, creative and culinary arts, and social justice.” Many local businesses, including Entergy New Orleans and Liberty Bank, have supported the vision of the Chases.

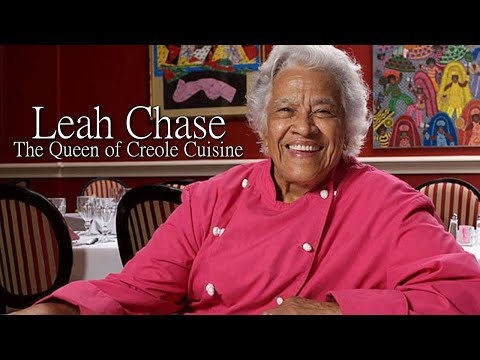

On June 1, 2019, Leah Chase, the “Queen of Creole Cuisine”, passed away. Preceded in death by her husband who died in 2016, she was surrounded by her loved ones including son, Edgar III; daughters, Leah and Stella; her siblings and grandchildren. Dooky Chase’s Restaurant is still in operation, being operated by her descendants.

Leah Chase was the recipient of numerous awards and accolades. They include the prestigious Loving Cup Award from The Times Picayune in 1997 and, according to the African American Chef Hall of Fame website “… a series of honors from the NAACP, the Weiss Award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews, the Torch of Liberty Award from the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, the University of New Orleans’ Entrepreneurship Award and the Outstanding Woman Award from the National Council of Negro Women.” Civil rights activist, healthcare advocate and New Orleans culture afficionado Rudy Lombard co-authored with Nathaniel Burton Creole Feast: 15 Master Chefs of New Orleans Reveal Their Secrets (1978). One of these master chefs featured was Leah Chase.

(No copyright infringement intended).

An avid collector of art, she has been captured in art. Leah Chase was featured in the book and traveling exhibit, I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America. She is the subject of Gustave Blache III’s series, Leah Chase: Paintings. Exhibited in 2012 at the New Orleans Museum of Art, where Chase was an honorary life trustee, Blache’s Cutting Squash is in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery and two of the paintings, including Leah Red Coat Stirring (Sketch), are owned by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

She had received several honorary degrees from several institutions including Dillard University, Johnson & Wales University, Loyola University New Orleans and Tulane University. Leah Chase was ranked among “Who’s Who of Food & Beverage in America” of the James Beard Foundation; inducted into the African-American Chefs Hall of Fame and received the Lifetime Achievement Award by the Southern Foodways Alliance. In 2009, the Southern Food and Beverage Museum paid tribute to Chase’s extensive work by naming a permanent gallery after her. It’s also said that she was an inspiration for the lead character, Tiana, in Disney’s The Princess and the Frog (2009), which was a modern version of the novel, The Frog Princess, by E.D. Baker. The acclaimed Food & Wine honored Dooky Chase’s Restaurant in 2018 by ranking it as one of the “40 Most Important Restaurants of the Past 40 Years”!

(No copyright infringement intended).

Her wonderful Creole fare and famed restaurant, the incredible artistic, cultural, philanthropic and political contributions Leah Chase made to the Black community and society led to her being honored by many institutions, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. She is prominently featured in its Culture Expressions Gallery. The other chefs honored are Hercules, who cooked for President George Washington; Patrick Clark, Edna Lewis and Joe Randall. The permanent display in tribute to Leah Chase contains her rose red chef coat, featuring her name embroidered in marigold stitching, that she wore when working.

“Food builds big bridges … If you can eat with someone, you can learn from them, and when you learn from someone, you can make big changes. We changed the course of America in this restaurant over bowls of gumbo. We can talk to each other and relate to each other when we eat together.”

~ Leah Chase

For greater enlightenment...

-

Leah Chase: The Queen of Creole Cuisine

-

Gumbo 101 with Chef Leah Chase

-

Remembering Leah Chase, the Queen of Creole Cuisine

-

GCIA, Leah Chase Interview in New Orleans

-

Meet the 93-year-old Woman Behind New Orleans' Best Fried Chicken | Eat. Stay. Love.

-

The Princess and the Frog - Trailer

-

Inside The Creole Restaurant That Inspired Disney's 'Princess And The Frog' | Legendary Eats

-

Who Is Edgar Chase?