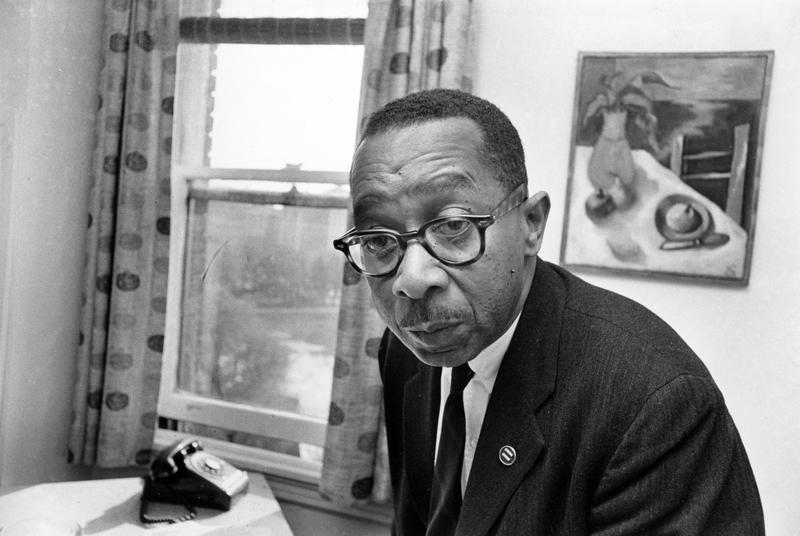

“Mr. Clark’s studies were widely credited with influencing the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision overturning racially segregated public schooling.”

~ Alan Richard, writer

Kenneth Bancroft Clark was born on July 14, 1914 to Arthur Bancroft and Miriam (née Hanson) Clark in the Panama Canal Zone. His parents were working class, as his father was as a laborer at the United Fruit Company and his mother was a skilled seamstress. Miriam felt that that the future of her children would be severely limited in Panama and emigrated to the United States when Kenneth was four years old and his sister, Beulah, was two years old. Arthur chose to remain behind in order to preserve his employment.

Settling in the Harlem community of Manhattan, Miriam Clark struggled greatly and often, the Clark family had to move between tenement apartments. Working several positions, including as an early shop steward with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, in order to provide for her and her children, she sacrificed much. However, she would not concede that education was unimportant and she was adamant that her children take advantage of opportunities available to them.

Despite living in impoverished and, at times, dangerous environments, Kenneth loved learning as well as being Black so life in Harlem had many great benefits. It was there that he was first introduced to and even interacted with many greats of the Harlem Renaissance. These persons include poet Countee Cullen, who taught Kenneth in junior high school; writers Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston; and bibliophile and curator, Arturo Schomburg.

It was expected that Clark, a stellar student, would attend a segregated high school, just as he did for elementary and junior high. Miriam Clark refused the assignation of Kenneth to the local secondary school, as the counselors were notorious for placing Black students into a vocational track, regardless of their academic accomplishments. Miriam fought for Kenneth to be placed on an academic path geared for higher learning at a university and he was enrolled in the prestigious George Washington High School.

At this time, the Great Depression occurred and it had especially devastated Blacks. They were struck particularly hard by this financial crisis, considering they had less resources than their White counterparts during times of economic prosperity. With their meager monies even greater diminished, the struggles for many African-Americans were compounded.

Kenneth B. Clark was especially interested in studying the impact of economics on his adopted community of Harlem. He soon suffered an experience of racial discrimination when he was not awarded a prize for his excellent performance in an economics class simply because he was Black. Clark did not let himself be deterred and in 1931, he both graduated from George Washington High School and became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

Upon graduation, Kenneth B. Clark matriculated Howard University, a historically Black institution of higher learning located in Washington, D.C. A premier university, its esteemed faculty included philosopher and “Father of the Harlem Renaissance” Alain Locke; sociologist, E. Franklin Frazier; political scientist Ralph Bunche, who taught Clark; and department chair of Psychology, psychologist Francis Cecil Sumner. Bunche was the first Black person to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950. Sumner, the first African-American to earn a doctorate in psychology (Lincoln University in 1920), became known as the “Father of Black Psychology”. Both Sumner and Bunche were highly influential on Clark.

Clark, who was mentored by Sumner, selected to study psychology, with an emphasis on Blacks, as his major. He assisted on a research project with Bunche, who believed that a true democracy cannot support segregation. A member of Kappa Alpha Psi, Clark acted as editor of The Hilltop, the university’s newspaper, and participated in civil rights activities, including demonstrations. His studies and work at the historically Black institution further emphasized the significance of political science and sociology theories’ application to reality. These would greatly inform his professional and personal growth while at Howard University, from where he earned his Bachelor of Arts in 1935 and Master of Science degrees in 1936.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Kenneth B. Clark was hired to teach psychology at his alma mater for the 1937-38 academic year and one of his students was Mamie Phipps. The child of affluent parents, her father was a physician and her mother worked in their medical practice. A high achieving learner she left her native Hot Springs, Arkansas to study mathematics and physics at Howard University. However, she was not supported by her professors in these fields and, at the suggestion of Clark, switched her major to psychology.

In 1937, Clark, prompted by Sumner, entered the doctoral program at Columbia University in the City of New York. While he studied in his former home city, he and Mamie remained in touch and their friendship blossomed into romance. Despite the objections of her parents who felt her formal education would be compromised for several reasons, Kenneth and Mamie eloped in 1937. The following year, she graduated magna cum laude from Howard University.

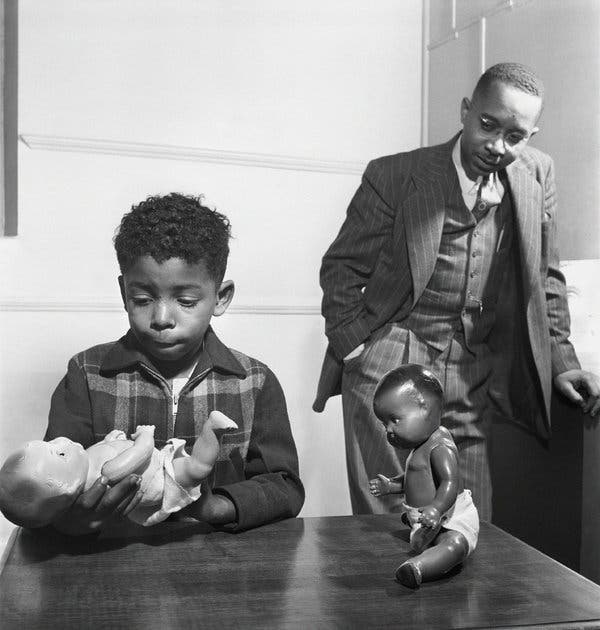

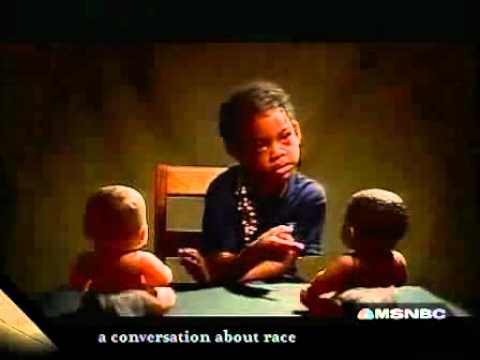

Following, Mamie Phipps Clark worked in the law offices of Charles Hamilton Houston, who famously fought racial discrimination. Known as “The Man Who Killed Jim Crow”, Houston led the Law School at Howard University and trained many attorneys, including future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, in the area of civil rights. At this time under Hamilton, she also worked in a nursery for African-American children. Developing on the self-identity work of Gene and Ruth Horowitz, Mamie Phipps Clark undertook research to apply to Black children’s sense of identity and esteem. This research would be the focus of her Master of Arts thesis, “The Development of Consciousness of Self in Negro Pre-School Children” at Howard University. In her work, she assessed the nursery children’s development of racial identity, incorporating items such as a coloring test and notably, “White” and “Black” dolls.

Supporting each’s research, Kenneth and Mamie soon collaborated professionally, including publishing their findings on race recognition and self-worth in academic journals and presenting at conferences. In 1939, a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship for Mamie was awarded, providing an additional three years of support for their research and her studies at Columbia University in the City of New York, where she too had entered to pursue her doctorate in psychology.

In 1940, Kenneth B. Clark graduated with his Ph.D. in Experimental Psychology, becoming the first African-American to earn a doctorate in psychology from Columbia University. Three years later, Mamie Phipps Clark earned her Ph.D. in Experimental Psychology, making her the first woman and second African-American to earn a doctorate in psychology from Columbia University. During this time, the Clark couple were blessed with two children: Kate Miriam, born in 1940, and Hilton Bancroft, born in 1943.

(No copyright infringement intended).

For the decade after graduating from Columbia, Kenneth B. Clark taught psychology and worked as a psychologist with the federal Office of War Information. His teaching began at Hampton Institute, another historically Black university, but he resigned due to differences between him and administration. He then became a professor at City College, City University of New York, in 1942 and held this position until he retired in 1975; he was the institution’s first full-time, tenured, African-American professor.

In 1946, the Clarks founded the Northside Child Development Center in Harlem. With donations from Mamie’s parents and volunteerism from their colleagues in psychology and social work, this Center, according to Encyclopedia.com, was “the first full-time child guidance center in Harlem to offer psychiatric, psychological and casework services to children and families.” A critical instrument of their work and outreach was intelligence testing. The Clarks used this to refute public schools’ ideology and disavow their intentional placement of minority children in programs for those with developmental delays. Mamie acted as the Director of the Northside Child Development Center until she retired in 1979.

By the 1950s, the Clark research was used in battling segregation. Their paper, “Effect of Prejudice and Discrimination on Personality Development” presented at the Mid-Century White House Conference on Children and Youth was highly influential in building with individuals and organizations. The organization with whom the Clark couple became most famous for collaborating with against segregation was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Having studied more than two-hundred Black children, the Clarks’ work detailed their findings of race’s influence on self-identity and esteem in “The Effects of Segregation and the Consequences of De-Segregation: a Social Science Statement”.

The psychologist couple concluded that segregation was psychologically destructive. This result was integral in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), that outlawed segregation in public education. Thurgood Marshall, an attorney of the NAACP who argued the case before the U.S. Supreme Court, used the Clarks research to illustrate the devastation Black children suffered due to legal segregation that all too often was not “separate but equal”, as per the judgement of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In giving their decision on Brown v. Board of Education, the federal court emphasized the importance of the Clarks’ work. The Court affirmed that segregation, according to Encyclopedia.com, “generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect the children’s hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.” This groundbreaking decision greatly impacted Blacks and their opportunities for personal, familial and community advancement.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Even though progress was being made with the ending of segregation in public schools, the Clark couple knew that that measures of economic and political empowerment had to be undertaken in order to address and heal the ills Blacks experienced brought about by poverty. Accordingly, in 1962, he co-founded Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU). The purpose of this organization was to develop educational and employment opportunities for those in need. In order to devise programs, the Clark couple undertook extensive research of factors impacting Harlemites. These factors include education levels, housing, income and incarceration. Experts in various career fields were sought to re-structure community institutions in Harlem. The HARYOU program inspired the War on Poverty program initiated by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Kenneth B. Clark actively promoted racial integration but his focus was always for the betterment, especially psychological, of Blacks. His books, including Dark Ghetto: Dilemmas of Social Power (1965), were especially enlightening and motivational for Black readers, significantly those who supported Black Power. In the biography sketch, “Kenneth B. Clark” on African American Registry, his Dark Ghetto was especially “popular among Black Nationalists because it compared the situation of Black citizens to that of colonized people.”

Clark continued to fight against segregation and blaze trails for other Blacks in psychology to follow. To meet these needs, he founded the Metropolitan Applied Research Center. Also serving as its president, he and others at this Center sought to assist those who were impoverished and felt powerless. The recipient of the Spingarn Medal by the NAACP in 1961, he became the first African American to be appointed to the New York State Board of Regents in 1966. Working to ensure that educational opportunities were equitable for all children, he was a member of this Board for twenty years. For the 1970-71 term, Kenneth B. Clark became the first Black president of the American Psychological Association (APA) and received its Gold Medal Award.

After the race riots ravaged the United States in 1967, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders was developed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Known as the “Kerner Commission”, Clark served as an expert, consulting on psychological and social issues in urban communities.

An advocate for racial integration, Clark was a board member and Chairman Emeritus of the New York Civil Rights Coalition until his death on May 1, 2005. Suffering with cancer, he passed in Hastings-on-the-Hudson, New York; he was ninety-years old.

(No copyright infringement intended).

The impact of his and his wife’s legacy is immeasurable. He was the recipient of a number of accolades, including the Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Award and the Presidential Medal of Liberty. Presented with the “Award for Outstanding Lifetime Contributions to Psychology” by the APA, he was only one of six psychologists to be gifted this honor.

In 2000, the Kenneth B. Clark Center at the University of Illinois, Chicago opened in honor of his powerful ethical and dedicated work. He was also gifted honorary degrees from nine universities, including Earlham College. This institution’s degree to both Kenneth and Mamie Phipps Clark was awarded in 2004 in honor of the 50th anniversary of their legendary work in Black psychology and civil rights. In 2017, the Department of Psychology at Columbia University in the City of New York, the Clarks’ alma mater, created the Mamie Phipps Clark and Kenneth B. Clark Distinguished Lecture Award in recognition of a senior scholar’s outstanding contributions to race and justice.

“A racist system inevitably destroys and damages human beings; it brutalizes and dehumanizes them, Blacks and Whites alike.”

~ Kenneth B. Clark

For greater enlightenment...

Social and Economic Implications of Integration in Public Schools (1965)

The Negro American (1966) by Kenneth B. Clark and Talcott Parsons

A Relevant War Against Poverty (1968)

Crisis in Urban Education (1971)

A Possible Reality (1972)

-

Landmark Cases: Brown v Board Doll Test (C-SPAN)

-

Simple Justice: The Social Science Evidence of Racism

-

Clark Doll experiments

-

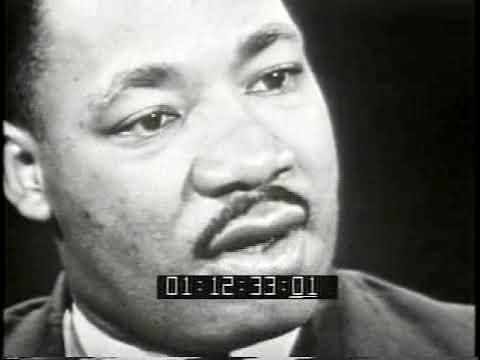

The Negro and the American Promise

-

Malcolm X interview 1963 at Kenneth Clark

-

Martin Luther King, PBS interview with Kenneth B. Clark, 1963

-

James Baldwin Interview with Kenneth Clark

-

Kenneth B Clark - Intelligence in the Service of Love and Kindness - 1984

-

Kenneth and Mamie Clark

-

Dr. Kenneth Clark 2.18.1983