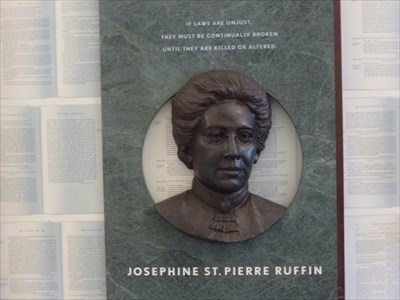

“Called ‘a woman of rare force of character, mental alertness and of generous impulses’ by Booker T. Washington, Ruffin dedicated her life to bettering the lives of women and African Americans both locally and nationally.”

~ National Park Service

On August 31, 1842, in Boston, Massachusetts, John St. Pierre and Elizabeth Matilda Menhenick welcomed their daughter into the world. The youngest of six children, the parents named her “Josephine”. Her father, of African and French ancestry, was from Martinique and her mother was from England. While Elizabeth led the domestic management of their home, John was highly esteemed as a leader in the African-American community of Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood. He attained great success professionally, as a tailor, and communally, having founded Boston Zion Church.

Strong advocates of education, the parents sent Josephine to matriculate schools in both Charlestown and Salem, Massachusetts as well as in New York City. Institutions in Boston were segregated and all too often, those servicing “Colored” learners were severely lacking in academic, financial and personnel resources essential to positive achievement and growth. Josephine graduated from the Bowdoin Finishing School in Boston, Massachusetts.

(No copyright infringement intended.)

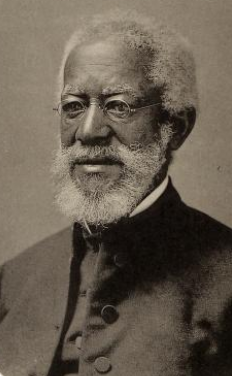

In 1858, sixteen year-old, Josephine St. Pierre married twenty-four year-old barber George Lewis Ruffin. Hailing from a free and wealthy Black family, his future achievements included several instances of being a trailblazer. Ruffin was the first African-American graduate of Harvard Law School (1869); the first African-American City Councilman to be elected in Boston and served two terms (1875-76 and 1876-77); and the first African-American judge in Massachusetts (1883). Their union would be blessed with five children. Sadly, one, Robert, passed away before he was even one-year old. The remaining four children would thrive and, thus, accomplished much; they are Hubert, an attorney; Stanley, an inventor; George, a musician; and Florida, a school principal. It was she who would be integral in the co-founding of their mother’s The Women’s Era.

After marrying, the Ruffin couple emigrated to Liverpool, England. This international move was undertaken in response to the decision rendered in the Dred Scott v. John F.A. Sandford case (1857). The decision, according to Britannica.com, “ruled (7–2) that a slave (Dred Scott) who had resided in a free state and territory (where slavery was prohibited) was not thereby entitled to his freedom; that African Americans were not and could never be citizens of the United States; and that the Missouri Compromise (1820), which had declared free all territories west of Missouri and north of latitude 36°30’, was unconstitutional. The decision added fuel to the sectional controversy and pushed the country closer to civil war.”

When the Civil War began, the abolitionist Ruffin family returned to the States and re-settled in the Black-populated community of West End in Boston. The motivating force for their repatriation was to recruit African-Americans for enlistment in the Union Army, most notably, the Massachusetts 54th and 55th regiments. The couple’s advocacy involved their work with the Sanitation Commission, caring for soldiers active in the field.

After the victory of the Union, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin continued to actively support interests, such as charity, literacy and suffrage, that were essential to Black progress. As shared in her biography on the website of the National Park Service, she “served on several charities that helped Southern Blacks. In the following decades, Ruffin participated in numerous clubs and service organizations in the Boston area, often skillfully maneuvering between White and Black communities to do so.” As such, she founded the Boston Kansas Relief Association in 1879. It collected and distributed resources to aid Exodusters, African-Americans who migrated and settled in Kansas.

A charter member of the Massachusetts School Suffrage Association (MSSA), St. Pierre Ruffin joined forces in 1869 with two leading White abolitionists and activists, Julia Ward Howe and Lucy Stone, to create the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The previous year, Ward Howe and Stone formed the New England Women’s Club (NEWC); St. Pierre Ruffin became a member of this organization during the mid-1890s.

(No copyright infringement intended).

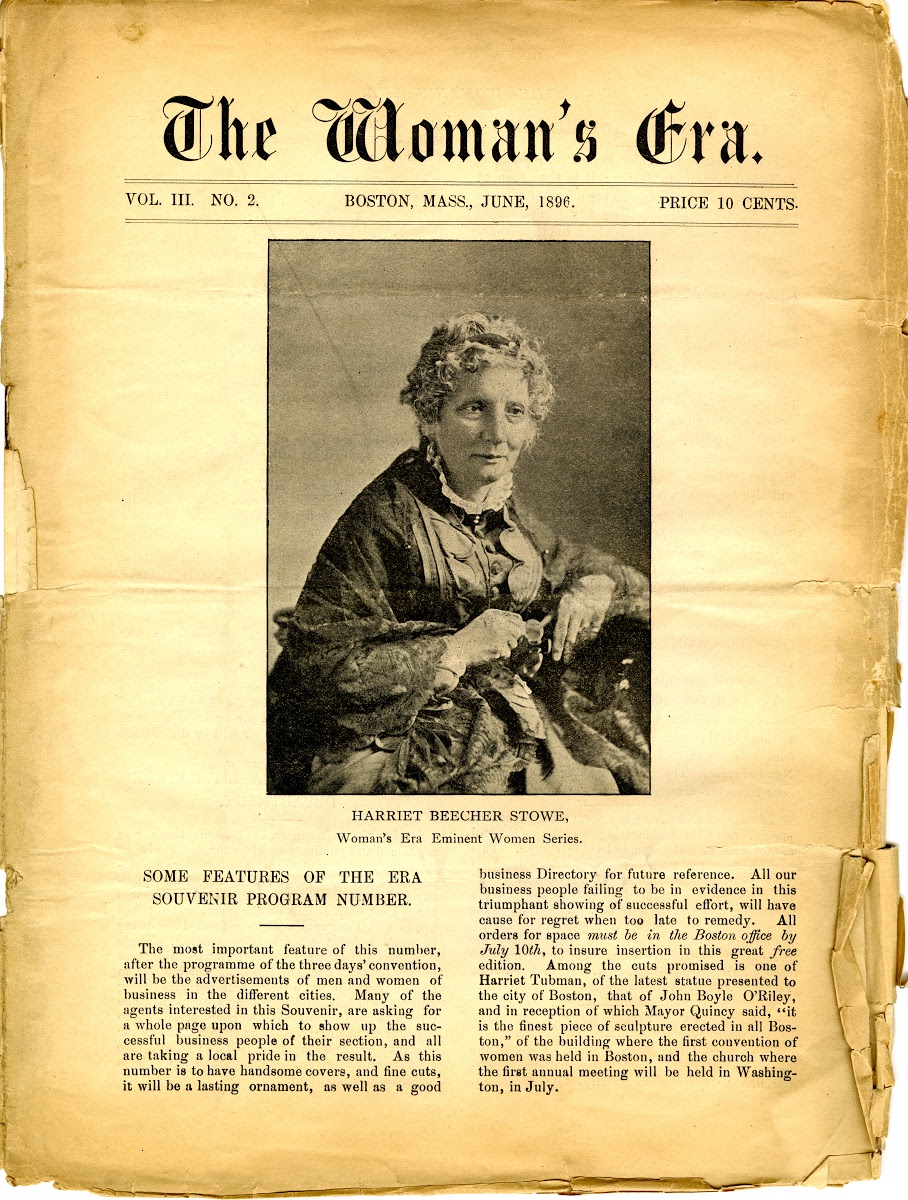

Sadly, George Lewis Ruffin passed away in 1886 at only fifty-one years old. Financially affluent, forty-four year-old Josephine and Florida, their daughter, founded the Women’s Era Club (WEC); educator and principal Maria Louise Baldwin was also instrumental in the club’s creation. A civic organization for African-American women, its outreach included conferences, community service projects and the publication, The Woman’s Era. Utilizing experience she gained from having been a member of the New England Woman’s Press Association as well as a columnist with The Courant, an African-American weekly, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin’s launch of The Woman’s Era was incredibly groundbreaking.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

Referenced by St. Pierre Ruffin as a “high class paper”, its target audience was middle and upper class African-American women. Covering topics ranging from education and etiquette to race-relations and suffrage, The Women’s Era (1894–1897) was the first periodical in the United States published by and written for African-American women!

(No copyright infringement intended).

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin continued to pioneer paths of unity and progress when, on July 29, 1895 at Berkeley Hall in Boston, she organized a three-day conference of representatives of forty-two other African-American women clubs from fourteen states. These clubs in attendance at the “First National Conference of the Colored Women of America” included the Ida B. Wells Club of Chicago and the Colored Women’s League of Washington. The purpose of this event was to align the efforts of the clubs’ expansive networks of cultured and educated members.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Guests speakers at this auspicious gathering included activist and educator Margaret Murray Washington, wife of Booker T. Washington, author, educator, presidential adviser and founder of the historically Black institution of higher learning, Tuskegee University; African-American scholar and sociologist Dr. Anna Julia Cooper; Anglo-American social activist and founder of The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison; African-American journalist and anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells; and African-American Episcopalian bishop and Black liberation activist Dr. Alexander Crummell. This convention was such a success that an extra day to meet at Charles Street Church to continue connecting was added, as, according to The New York Times, it was “the first movement of the kind ever attempted” in the United States!

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

Resulting from this conference was the creation of the National Federation of Afro-American Women (NFAAW). The next year, this federation merged with the Colored Women’s League (CWL) of Washington to create the National Association of Colored Women. Esteemed educator and activist Mary Church Terrell was elected as its first president and St. Pierre Ruffin was elected as its first vice-president. According to the biography of “Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin” at the National Women’s Hall of Fame website, her “continued resistance of all-White national women’s clubs reinforced her commitment to the importance of the African-American clubwomen’s movement, and she remained an active participant throughout her life.” As editor and publisher, St. Pierre Ruffin also used her illustrated, monthly national publication, The Women’s Era, as the national news arm of African-American women. This paper would “Help to Make the World Better”, as its slogan proclaimed.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1900, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC) held their national convention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Because she was a member of the all-Black Woman’s Era Club and recently-integrated New England Woman’s Press Club as well as the New England Woman’s Club, Josephine planned to represent each. However, Southern White women, who dominated this convention, balked at the idea of St. Pierre Ruffin having any power to represent the two New England clubs and outright refused to acknowledge any credentials of the Woman’s Era Club. While the administrators conceded to “allow” her a seat as a representative for the two White clubs, no allowance was offered for the Black club. According to the thumbnail sketch on Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin at blackwomensuffrage.dp.la, “ A White conference attendee even attempted to grab her badge from her … ”

St. Pierre Ruffin adamantly refused any “participation” and the blatantly racist treatment towards her and Black clubs garnered great criticism from many. Her reasons for joining White clubs were significantly motivated beyond the sincere friendships she had with Ward Howe, Stone and other White club members. She constantly spoke out against the dearth of interest, involvement and commitment of White clubs, notably, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, who refused to assist in alleviating the double burdens of sexism and racism under which Black women suffered. For the next several years, the discrimination at the GFWC convention would play out in the press as well as among White club chapters, significantly those in Georgia and Massachusetts. Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin ultimately issued a formal statement advising African-American women that they would be best served by centering their focus, energies and resources on issues that pertained to their own communities.

The seemingly tireless activist continued to lead and serve, even aiding, as a charter member, in the creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the League of Women for Community Service (LWCS).

On March 13, 1924, in her home, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin passed away from nephritis; she was eighty-one years old. Her rich legacy continues to be honored in contemporary times, as she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame (1995) and a bronze bust of her was installed at the Massachusetts State House (1999). The subject of Teresa Blue Holden’s book, Earnest Women Can Do Anything”: The Public Career of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, 1842-1904, she and her husband, George Lewis Ruffin, are featured in a permanent exhibit at the West End Museum in Boston. Additionally, their home on Charles Street is a designated site on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail.

(No copyright infringement intended).

“We are women, American women, as intensely interested in all that pertains to us as such as all other American women; we are not alienating or withdrawing, we are only coming to the front, willing to join any others in the same work and welcoming any others to join us.”

~ Josephine St. Pierre