“John Sengstacke … wanted to make an impact on the world by adding value. He knew it was not only persistence but also abilities that were needed to break through the wall of segregation and inequality …”

~ Pastor Bill Winston, Living Word Ministries

On November 25, 1912, in Savannah, Georgia, John Herman Henry Sengstacke was born to Herman Alexander and Rosa Mae (née Davis) Sengstacke. The baby was named after his paternal grandfather, a Congregationalist minister and educator of Woodville, Georgia. The elder John H. Sengstacke also was a publisher of two Black newspapers, including the weekly Woodville West End Post. He would marry Flora Butler Abbott, a widow and mother of a one-year old son, Robert. Abbott hailed from St. Simon’s Island, Georgia and had been formerly enslaved. John and Flora would have seven children, including Herman Alexander, who was called by his middle name.

Descending from a long line of Protestant ministers, Reverend Alexander Sengstacke also worked as an educator because he wanted to help Blacks improve their lives; Rosa served as a missionary in the Church.

John H.H. Sengstacke was reared with his two brothers and three sisters near Woodville. As a young boy, John H.H. Sengstacke was very interested in the work his father, Alexander, performed at the family’s newspaper, the Woodville West End Post. Thus, his father mentored him and John worked his way from being a printer’s apprentice to chief assistant to his father.

His uncle, Robert Abbott, who had been given the surname “Sengstacke” as his middle name to illustrate his membership in their family, noticed his nephew’s keen interests and deep commitment to his father’s paper. John’s passion and dedication moved Abbott to name John as his successor to his own newspaper, The Chicago Defender, one of the most popular and successful Black-owned newspapers in the United States.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Robert Sengstacke Abbott founded his publication in 1905, after earning his law degree from Kent College of Law in Chicago. The newspaper experienced immense growth with The Great Migration, because it detailed the diverse opportunities available for Blacks to drastically improve their lives. It would become part of a covert network, involving Pullman porters, that worked diligently to inform Blacks in the American South who suffered greatly under overt racial discrimination, Jim Crow segregation, inequality, violence and murder. In an article, “The Legacy of John H.H. Sengstacke: How He Influenced Black America” for The Chicago Defender, journalist Mary L. Datcher wrote, “The power of the Defender reached beyond the urban cities of the North. As the Jim Crow South tightened its grip on Blacks, the paper was smuggled on trains by Pullman Porters traveling below the Mason-Dixon line. Many would wait patiently as bundles would be thrown over the railings through rural parts of Southern states — with news of jobs and a better quality of life in Northern cities such as Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland. People flocked in the thousands searching for a better life and a better way in urban cities, fueled by stories of prosperity and hope in the Defender.”

Under his uncle’s tutelage and patronage, John H.H. Sengstacke spent his summers learning the operations at the Defender. After graduating high school, Sengstacke attended Hampton Institute, a historical Black college in Hampton, Virginia and Abbott’s alma mater. While at Hampton, Sengstacke covered stories of interest for university’s newspaper, the Hampton Script. Upon graduating with his Bachelor of Science degree in business Administration in 1934, Abbott continued to support his nephew’s advanced education, subsidizing his academic interests at various institutions within Northwestern University, the Mergenthaler Linotype School and The Chicago School of Printing.

In 1936, the work of Abbott and Sengstacke culminated in Sengstacke being appointed Vice President and the General Manager of The Robert S. Abbott Publishing Company. While the promotion of Sengstacke was warranted, as he was more than worthy of his hire, it was also necessary to meet the demands of Abbott’s growing publishing empire. Abbott, who had become a millionaire by 1918, launched the Louisville Defender, headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1933 and the Michigan Chronicle in Detroit, Michigan in 1936. Sengstacke worked, even composing editorials and articles, between the three newspapers. He was one of the primary founders of the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA), created in 1940. The purpose of the NNPA was to unite Black publishers in order to increase their presence and power in the publishing industry. In his lifetime, he would serve seven terms as president of the NNPA. Sengstacke enacted several modifications that drastically impacted the Black publishing industry. One of the most significant modifications was incorporation of advertising, as opposed to subscriptions, to become the most important source of financial support.

In 1939 John H.H. Sengstacke married Myrtle Elizabeth Picou, a woman of Creole heritage from New Orleans, Louisiana. They had three children: John Herman Henry III; Lewis Willis; and Robert Abbott, named in honor of his uncle. An activist, Myrtle worked in community outreach, including in art, culture and political activities.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1940, in Chicago, Robert S. Abbott passed away from Bright’s disease; he was sixty-nine years old. In his will, Abbott left ownership and control of his company to his nephew, John. Only twenty-eight years old, John H.H. Sengstacke became president of the chain of newspapers, becoming one of the most important Black persons in America. However, his position was challenged by Abbott’s widow, Edna Abbott; his legal battle against her would last for ten years. In 1950, he finally gained complete control of the publishing company. During this decade of uncertainty, Sengstacke ensured that the newspaper and its publications continued to be printed; in fact, the Chicago Defender never missed an issue!

With the beginning of World War II, John H.H. Sengstacke, like other editors of newspapers, was exempted from military service. He served as chairman of the U.S. Office of War Information Advisory Committee on the Negro Press. In his paper, he exposed the racial discrimination that Black military personnel experienced and shared their accomplishments. In owning one of the most successful newspapers in the United States, he leveraged his position to better advantage African-Americans. One of his aims was to desegregate the military, especially due to the sacrifices African-Americans made during World War II. Sengstacke accepted a position from President Harry S. Truman to serve on a commission he formed in 1948 to end segregation in the military, which began in 1949.

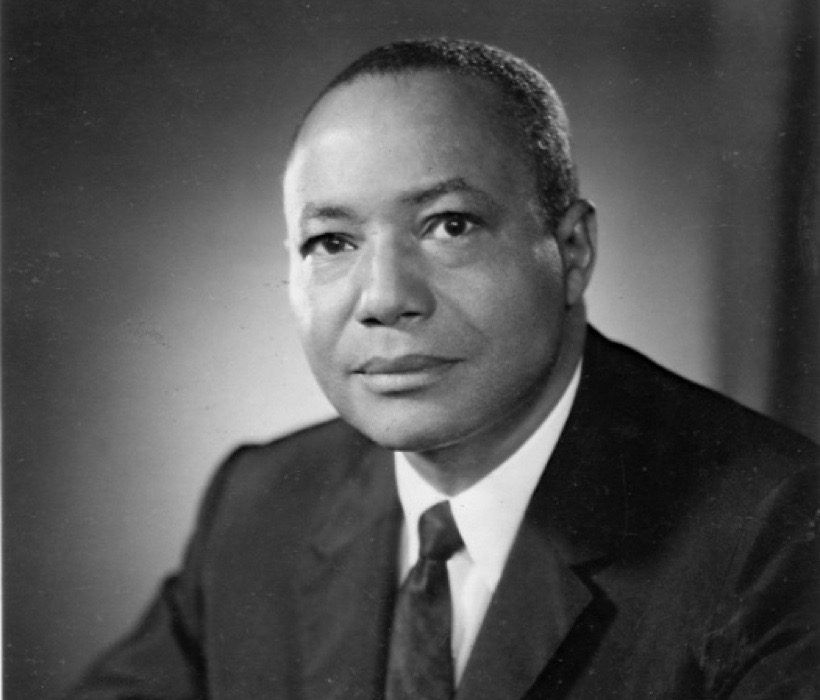

This image was sourced from The Chicago Defender (No copyright infringement is intended).

He worked with several U.S. presidents, including Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson to meet his goals of improving the lives of Blacks in America. His efforts led to the inclusion of African-American reporters in the White House press gallery, especially during presidential press conferences. It should be noted that the first African-American journalist to cover the White House was Harry McAlpin, who worked for The Chicago Defender. His work developed opportunities for Blacks working in the federal government, including the U.S. Post Office; and removal of the color barrier in mainstream professional baseball. In 1947, he and Paul Robeson met with Brooklyn Dodgers owner, Branch Rickey, and the baseball commissioner, Happy Chandler, that ultimately led to the entry of Jackie Robinson into Major League Baseball (MLB). Also, that year, Sengstacke was one of fifteen co-founders of Americans for Democratic Action. Co-founders of the organization included Pulitzer Prize recipient and National Book Award winner, journalist Joseph Lash; civil rights activist and leader of the United Automobile Workers (UAW), Walter Reuther; and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

All these actions of John H.H. Sengstacke positively impacted many Americans, especially African-Americans who took part in The Great Migration. From 1940 to 1970, approximately five million Blacks fled the American South. Already owning the Michigan Chronicle, (the Louisville Defender was sold by Abbott in 1936), another newspaper, the Tri-State Defender, was bought in 1952. Published in Memphis, Tennessee, it covered Tennessee, Arkansas and Mississippi. A dramatic increase of Black settlement in urban areas of the North and Midwest led to the need to cover issues of Black life more often. In order to meet this need, in 1956, Sengstacke transitioned publication of The Chicago Defender from weekly to daily; it became one of only three Black daily newspapers published at that time. He also promoted greater coverage of issues significant to Chicago; because of this approach, he was able to increase local circulation and advertising promotion.

In 1945, Sengstacke created The Chicago Defender Charities, which produced the Bud Billiken Parade. The parade, founded by Robert S. Abbott in 1929, is a day-long event that occurs every second Saturday of August. Celebrating Black family, especially children and youth, the Bud Billiken parade has grown to become the largest African-American parade in the United States and the second largest, only after Macy’s annual Christmas parade in New York City, in America.

In 1966, the Pittsburgh Courier Company, owner of the Pittsburgh Courier, which was considered to be one of the most premier Black newspapers, was bought by John H.H. Sengstacke. His purchase of this company also added seven other newspapers under his control. In 1967, he re-launched it as the New Pittsburgh Courier and in 1974, appointed Hazel B. Garland as its editor-in-chief. Her appointment made her the first African-American woman to be the managing editor of a national newspaper. In 1976, the New Pittsburgh Courier received the John B. Russwurm Award for “Best National African-American Newspaper”.

From the 1970s to the 1990s, Black newspapers experienced a decline. The reasons for this decline included integration of Black writers and culture into mainstream publications; Sengstacke’s conservative positions in the Democratic Party; lack of strong financial support from advertising and decreased quality of content.

Despite these factors, John H.H. Sengstacke remained highly active in the Black community, especially in Chicago, and his chain of newspapers remained the largest chain of African-American owned newspapers in the United States. He was the recipient of numerous awards and accolades, including receiving from the National Council of Negro Women their “Award of Excellence” (1975); being named by Ebony as one of the “100 Most Influential Black Americans” (1975); and by the International Biographical Centre of Cambridge, England as “International Man of the Year” (1992). Posthumously, Sengstacke was awarded the Presential Citizens Medal by President Bill Clinton.

Perhaps one of his greatest contributions was leading the drive in raising $50 million for the building, re-opening and modernizing of Provident Hospital, which is managed by Cook County Hospital. Its health center is named after Sengstacke.

On May 28, 1997, John H.H. Sengstacke passed away from complications of a stroke; he was eighty-four years old.

It was detailed in his will that The Chicago Defender and other publications be sold after his passing. Ten years after his passing, Real Times Media, Inc. bought the collection of publications that the Sengstacke family had owned and managed for almost ninety years. Investors in the media company have family and business connections with John H.H. Sengstacke. The Abbott-Sengstacke Family Papers were donated to the Chicago Public Library by Robert A. Sengstacke.

The NNPA, whose name was changed from the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association to the National Newspaper Publishers Association in 1956, still thrives. The NNPA remains a highly influential organization, containing more than two-hundred, Black-owned publications, including The Chicago Defender, as members. The organization’s member publications are of the United States and Virgin Islands. According to its website, the NNPA has “a combined readership of 15 million, and the organization has created an electronic news service, BlackPressUSA website, which enables newspapers to provide real-time news and information to its national constituency” and has “ … launched NNPA Media Services — a print and web advertising placement and press release distribution service.”

The vision of John H.H. Sengstacke continues to educate, enlighten and empower the Black community.