“Randall’s expertise in Southern cuisine is held in such high esteem that he was honored and featured in the Culture Expressions Gallery of the newly opened Smithsonian Institute of National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., along with chefs Edna Lewis, Patrick Clark, Leah Chase and Hercules, George Washington’s enslaved cook.”

~ African Americans Chefs Hall of Fame

Born on July 23, 1946 in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, Joseph Randall has been inspired by Southern food all his life. Reared in Harrisburg, he enjoyed this unique fare that was prepared by his mother, who hailed from Virginia. Also, his uncle, Richard Ross, was a caterer and restaurateur in Pittsburgh and owned Ross’ restaurant in Large, Pennsylvania. It was with his “Uncle Dick” where a teenage “Joe”, as he was called, worked as a busboy and dishwasher.

After graduating from William Penn High School in Harrisburg, a seventeen-year old Randall enlisted for service in the United States Air Force. It was during his time stationed at Turner Field in Albany, Georgia where he personally acquired his great appreciation for Southern fare. His duties included cooking in flight line kitchens. However, his enlistment was terminated early when his father, Dr. Joseph A. Randall, passed away. Having served almost two years, he received a hardship discharge and returned home to assist his mother in Pennsylvania.

In 1964, he was hired by the Chalet Restaurant, owned by Jerry Veronikis, in Dillsburg, Pennsylvania. He worked six days per week and earned ninety cents an hour. By 1966, Joe Randall was hired to apprentice under Robert W. Lee, an African-American executive chef at the Harrisburger Hotel. A native of Atlanta, Georgia, Lee was the first Black executive chef in Harrisburg. In the profile on Randall in Black Culture Connection at the PBS website, he shared about his mentor, “There were young White cooks who didn’t want to work for him. He brought Atlanta-based cooks who had already worked for him to Pennsylvania and ran that hotel with an entire African American crew. I came along in the ‘60s and was one of the last to get his grace. It took me two years as an apprentice and I finally earned a job.”

When the hotel restaurant closed, Randall then worked across the street underneath Frank Castelli, executive chef at the Penn Harris Hotel. From Castelli, he learned how to cook classical European cuisine.

For centuries, Blacks have been the foundation of the agriculture and food service. With the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, many African-Americans were discouraged from remaining or even entering both these industries. Aside from the severely limited opportunities historically available and the myriad of negative experiences, many Blacks wanted to take advantage of entering new career fields. Even if one earned their credentials as a chef, they were still classified by the U.S. Department of Labor as a domestic worker. This was particularly damning for Blacks in the South who comprised the majority of workers in the food industry. Fortunately, chefs were classified as professional workers in 1977.

Also in 1977, Joe Randall met his future wife, Barbara, when he attended a service at Christ Temple Apostolic Church in Sacramento, California; she was an usher. After becoming engaged on New Year’s Day, they married on July 1, 1978. They were blessed with three children, Cari, J. Christopher and Kenneth.

For more than two decades, Joe Randell would work in diverse environments of hospitality. These settings were more restaurants and hotels and even country clubs. He served as executive chef at numerous sites, including the award-winning Cloister Restaurant in Buffalo, New York and Fish Market Restaurant in Baltimore, Maryland. Randall also taught at three culinary schools and three universities, including at the Kellogg Ranch of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.

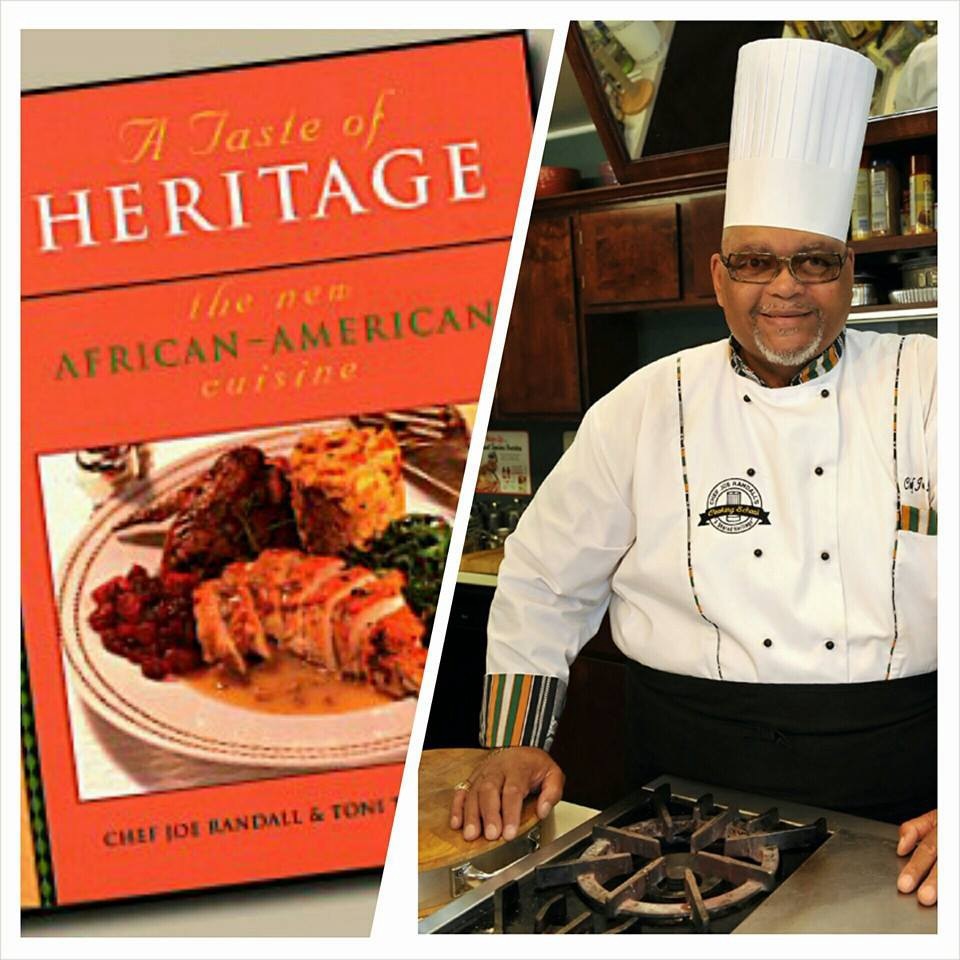

By the 1990s, he had become a leading figure among Black chefs and could be seen in his uniform whites handsomely emblazoned with Kente cloth. An intricately woven textile historically worn by royalty in Ghana, Joe Randall had it customized to his professional attire as it displayed his great pride in being an African-American chef.

In 1999, Randall accepted a position as chef and director of food services at the Savannah College of Art and Design. There, he operated in venues such as the Casey House, the Griffin Tea Room and the Streamline Diner.

Inspired to extend his expertise from an educational vantage, he opened Chef Joe Randall’s Cooking School at 5409 Waters Avenue in 2000. Hailed as the “Dean of Southern Cuisine”, Joe Randall’s vision was to spread “the gospel of authentic Southern cuisine to all comers”, according to his profile at the website of Southern Foodways.

His stellar reputation and the school’s excellent training drew students from around the world. In his school, he also shared what he learned from his mentor, Lee. Respect of those around you in a kitchen, active maintenance of equipment and a positive demeanor were essential to being successful in enduring the often hectic conditions of being a cook or chef.

Randall also emphasizes the importance of Southern cooking, which involves the Low Country, Sea Islands and fare from the Atlantic coast. Accepting that various factors, such as effective time management and health concerns, have impacted its creation, he has been on a mission to retain and promote the legacy of this type of dining from a Black cultural vantage.

He is a founding board member of the Southern Food Alliance and the Chair of The Edna Lewis Foundation. Lewis, considered the “Grand Dame of Southern Cooking”, was great friends with Randall. His mission at the Foundation, as per the profile of Joe Randall at the African American Chefs Hall of Fame website is “to fulfill her dream to preserve older cooking recipes and protect Southern cuisine and its heritage in Black kitchens.” An acclaimed chef, his affiliations have also included the American Academy of Chefs and the American Culinary Federation.

(No copyright infringement intended).

After fifty-three years in culinary service, Joe Randall announced in November 2016 that it was time for him to retire. In just the sixteen years of operating his cooking school, he had taught two generations of cooks! He felt he was ready for a new stage in his life and he wanted to spend more time with his wife, who Randall credits for his success. Barbara, who often worked weekends and evenings with him after her day job, happily agreed with his decision.

In January 2017, a gala celebrating the rich and expansive legacy of Joe Randall was held at the Hyatt Regency Savannah. Approximately 150 guests were treated to a reception and six-course meal created by Randall and nine other executive chefs who traveled as far as Washington D.C. to be a part of such a momentous affair. All the fare was sourced from Randall’s recipes. At this event, the Dean shared that its purpose was not as a retirement dinner but simply to inform the closing of the cooking school.

While he and several of his chef friends would hold an occasional cooking class, Randall proudly announced that their school site would act as the African American Chefs Hall of Fame. Jan Skutch wrote in “Savannah Chef Joe Randall to Keep Cooking School Open as Hall of Fame to Black Heritage” for Savannah Now, that the purpose of the Hall of Fame is “to recognize the history and impact of Black chefs on American cuisine and for periodic cooking classes.

For certain, the African American Chefs Hall of Fame has existed for years on the internet. However, Randall felt that an actual building would greater guarantee its purpose. He wants it to house material such as artifacts, films, portraits, recipes and other primary documents. In “Savannah’s Chef Joe Randall is Transforming His Famous Cooking School to Honor His African-American Mentors and Peers” featured on the St. Joseph/Candler website, the Dean advised, “This kind of physical building is needed to document the history … Otherwise, it’s too easy for it to get forgotten about.”

His great pride and activism in Black food heritage, vast knowledge of Southern fare and immense contributions to American culture has led to him being honored by many institutions, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. He is prominently featured in its Culture Expressions Gallery. The other chefs honored are Hercules, who cooked for President George Washington; Leah Chase; Patrick Clark and, of course, Edna Lewis. Randall has not only worked with Chase and Clark but is friends with the two extraordinary chefs. In the permanent display in tribute to Joe Randall are his book, A Taste of Heritage: the New African American Cuisine and his 40-year-old colander.

“Food is culture. It’s a part of any people’s culture. And when we talk about the South, you talk about hospitality, food becomes an intricate part of the presentation of the hospitality.”

~ Joe Randall