“Honestly, I can’t think of a single other soprano or mezzo-soprano with anything remotely approaching her sound … It was almost like a wall of sound coming at us, but extremely beautiful and consistent”

~ Renée Fleming, legendary soprano

On September 15, 1945 in Augusta, Georgia, Silas and Janie Norman welcomed a baby girl into their lives; they named her Jessye. Her parents were professionals of the Black middle class, her father worked selling insurance and her mother taught school. Though amateurs, her family was involved with music. Her father sang in the choir and her mother and grandmother played the piano, which would also be taught to Jessye and her five siblings.

A bright student, Jessye knew from a young age that she wanted to sing. Outside of familial influences, she was initially inspired by the powerful and beautiful voices of Sister Childs and Mrs. Golden, two women who attended Mount Calvary Baptist Church. It was at this church where her family was members and she began singing gospel songs at only four years old. Three years later, she entered and placed third in her first vocal competition. In her performance of a song, she forgot parts of the lyrics. However, this was indeed a learning lesson for her, as she was quoted in The New York Times about this incident by reporter Emily Langer. In “Jessye Norman, Acclaimed Operatic Soprano, Dies at 74” of The Washington Post, Langer tells of how Norman stated that “she flubbed the second stanza of the hymn ‘God Will Take Care of You’. I guess He has taken care of me,” she quipped. ‘That was my last memory slip in public.’”

Her life forever changed when she was gifted a radio in celebration of her ninth birthday. On it, she listened to various types of shows and genres of music, most notably, opera. On Saturday afternoons, Jessye and her family listened to performances of the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. She was especially inspired by African-American opera singers, Marian Anderson, Mattiwilda Dobbs and Leontyne Price. She felt these women laid the foundation that allowed her to believe that she too could one day professionally perform internationally.

Jessye Norman deftly balanced her academics and training at Charles T. Walker Elementary School, A.R. Johnson Junior High School, the Interlochen Center for the Arts and Lucy C. Laney Senior High School with formal lessons from vocal coaches including Rosa Harris Sanders Creque.

Her dedication and discipline served her well. In 1963, Norman accepted a full scholarship to study voice under Carolyn Grant at Howard University, a historically Black institution of higher learning located in Washington, D.C. She performed as a soloist and with the university choir and at Lincoln Temple United Church in Christ. Becoming a member of Gamma Sigma Sigma in 1964, she was a founding member of the Delta Nu chapter of Sigma Alpha Iota international music fraternity the following year.

In 1967, Jessye Norman graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in music and she soon began studying at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, Maryland. This was followed by her matriculation at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre and Dance in Ann, Arbor, where she earned a Master of Arts degree in 1968.

Because of limited opportunities in the United States for a professional, African-American woman opera singer, Norman relocated to Europe. Her first year there, 1968, she won the Bavarian Radio Corporation’s International Music Competition in Munich; this is the largest international classical music competition in Germany. The next year, she signed with Deutsche Oper Berlin and debuted as “Elisabeth” in Richard Wagner’s Tannhäuser.

For almost a decade, Norman performed with Italian and German opera companies. She could sing contralto to dramatic soprano. She performed in productions, including George Handel’s Deborah and Giacomo Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine, and played the lead in Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida, opening in 1972 at La Scala in Milan and as Cassandra in Les Troyens by Hector Berlioz at The Royal Opera in London. Her physical and vocal beauty were powerful, both soothing and arresting.

Also in 1972, Jessye Norman defied convention when she performed segments from her role of “Aida” in tribute to the 50th anniversary of the Hollywood Bowl. This concert, celebrating the famous amphitheater, further endeared her to frequent opera attendees and introduced her to those unaccustomed to the unique musical art. During this time, she traveled between the States and Europe.

from Britannica

(No copyright infringement intended).

By 1975, Norman performed exclusively as a soloist and recitalist. Her reason for this was because she wanted to perform opera as a career and understood that her voice needed to mature. Refraining from this type of activity, she became just as highly praised for her vocal interpretations of prominent composers such as Johannes Brahms, Franz Schubert and Gustav Mahler.

Returning to staged operas in 1980, she performed the title role in Richard Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos; it opened in Germany at the Hamburg State Opera. Two years later, Jessye Norman returned to America, where she performed that year with the Opera Company of Philadelphia. Her roles were “Jocasta” in Igor Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex and “Dido” in Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas.

In 1983, she debuted at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City when she performed as “Cassandra” in Les Troyens. Starring Plácido Domingo, the famed opera was conducted by James Levine. Her inaugural performance was in honor of the famed opera company’s 100th anniversary; she continued to perform at the Met until 2002. Also in 1983, Norman released Four Last Songs by Richard Strauss, possibly her most popular and loved recording.

From the mid-1980s to the 2010s, Jessye Norman continued to excel and achieve, accomplishing across diverse forms of music and art. In “Majestic American Soprano Jessye Norman Dies at 74” by Ted Robbins for All Things Considered of NPR, she spoke of her love for singing and her varied interests in performing. Affirming her passion, she recalled, ‘My parents told me that I started singing at the same time as I started speaking’ … The little girl from Augusta, Ga., with the big voice sang in church, school — and, she said, a few unusual venues. ‘I’d sing for the opening of a supermarket, as I always say. There was even an opening of a car wash at some point. They weren’t, sort of, very elegant settings all the time.’”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Jessye Norman expressed this passion in genres many would not think she performed. However, she loved to sing and her tastes extended from spirituals, pop and R&B to the blues and jazz, especially music of Duke Ellington, one of her favorites. In the Huizenga piece, soprano Renée Fleming affirmed, “The scope of her career is unique … She was performing at such a high level, but very often not singing mainstream repertoire — not the bread-and-butter Italian repertoire. Singing with her own template, as it were, and still being beloved and lauded everywhere she sang.”

Growing up in the segregated South did not deter her vision of being a professional opera singer. The bravery she had shown as a youth, integrating public accommodations such as lunch counters, prepared her to press forward in a career field where few looked like her or shared her life experiences. She praised Anderson, Dobbs and Price who made it possible for her to perform opera in foreign languages, including French and German, and overseas. In The Washington Post article by Langer, Norman declared, “It’s unrealistic to pretend that racial prejudice doesn’t exist. It does! It’s one thing to have a set of laws, and quite another to change the hearts and minds of men. That takes longer. I do not consider my blackness a problem. I think it looks rather nice.”

Jessye Norman positively influenced countless others, especially Black artists. In And So I Sing: African-American Divas of Opera and Concert, author Rosalyn M. Story expounded on the enormous impact Norman had on Black singers. According to Story, the gifts, talents, dedication and skills of Norman were greatly supported by her sense of power, self-determination and generous spirit, thus, rendering her iconic.

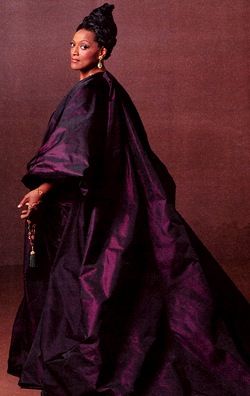

from Pinterest

(No copyright infringement intended).

Her outreach extends beyond performing for traditional opera audiences and include writing. Jessye Norman’s memoir, Stand Up Straight and Sing! was published in 2014. Its title comes from an admonition that her mother used to say to Jessye during her early childhood. In her reflection on her life, she reflects in her memoir that she is from “a specific place and time in the history of our nation, in the Deep South, where our people marched, bled, and soldiered their way through the civil rights movement … Every voice needed to find its own place … its own platform from which the cry for freedom and equality could be heard.”

In 1989, Jessye Norman, wearing an original design by Azzedine Alaïa, performed La Marseillaise at the Place de la Concorde of Paris. It was in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution. Her rendition of the French national anthem inspired South African poet Lawrence Mduduzi Ndlovu to compose, “I Shall Be Heard”. This poem, dedicated to Norman, appears in his 2018 collection of poems, In Quiet Realm; she wrote the foreword to this book.

She performed in the 1996 Summer Olympics Opening Ceremony and at the second presidential inaugurations of Ronald Reagan (1985) and Bill Clinton (1997). Norman collaborated with African-American greats including choreographer Bill T. Jones, jazz musicians Ron Carter and Grady Tate, and opera soprano Kathleen Battle.

Perhaps what most pleased her was establishment of the Jessye Norman School of the Arts. Opening in 2003 in her home city of Augusta, Georgia, she and the Rachel Longstreet Foundation collaborated to offer a tuition-free, performing arts after-school program for economically-disadvantaged students of promise.

Norman was highly involved with the school and its continuous development. According to its website, the school “enabled her to support and see first-hand the extraordinary work of an equally dedicated staff of teachers and auxiliary personnel. Students who would otherwise not be able to avail themselves of private tutelage in the arts grew into the fullness of their talents and gifts as they developed their own sense of community and citizenship. She absolutely glowed at any mention of The Jessye Norman School for the Arts and was grateful indeed for this tangible, living opportunity to address the need for education in the arts in the town where her own studies and training began.”

Her activism also manifested in her support of and involvement with institutions and organizations including the City-Meal-on-Wheels in New York City, Dance Theatre of Harlem, the Elton John AIDS Foundation, the National Music Foundation, the New York Botanical Garden and the New York Public Library. Norman served on the board of the Augusta Opera Association, Paine College and the S.L.E. Lupus Foundation, of which she was a spokesperson. She also served as a spokesperson for Partnership for the Homeless.

Norman received numerous accolades and honors. These include, according to her biography on her school’s website, “forty honorary doctorate degrees from colleges, universities, and conservatories around the world, five Grammy awards including the ‘Lifetime Achievement Award’, the National Medal of the Arts received at the White House from President Obama in 2010 and (she) was a Kennedy Center Honors recipient. In France, an orchid was named for her by the National Museum of Natural History. She was a Commandeur de L’Orde des Arts et des Lettres and was an Officier of the Legion Francaise.”

Image of Jessye Norman is from NPR (No copyright infringement intended).

Norman was still singing in public the year before she passed. Honored as a “Library Lion” by the New York Public Library in autumn 2018, Jessye performed a duet with Fleming. In the Robbins article, Fleming reminisced, “We brought her a microphone — she stayed in her seat, I was onstage … We performed [Offenbach’s] ‘Barcarolle’ together and there was not a dry eye in the room, including me. Just to hear that sound, it was still glorious. Just a magical moment I will cherish.”

On September 30, 2019, Jessye Norman died from septic shock and multi-organ failure that was secondary to complications of a spinal cord injury she had sustained in 2015; she was seventy-four years old.

A public funeral was arranged in Augusta and those who spoke on the program included actor Laurence Fishburne, arts administrator Sir Clive Gillinson and Mayor Hardie Davis. Performances in tribute were made by mezzo-soprano J’Nai Bridges, jazz musician Wycliffe Gordon and students from Spelman College, Morehouse College and her own Jessye Norman School of the Arts.

The Metropolitan Opera House also held its own public tribute to Jessye Norman in New York City. Among those presented on the program at the gala were playwright Anna Deavere Smith, arts administrator Peter Gelb, bass-baritone Eric Owens and Fleming. The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and the Dance Theatre of Harlem also performed.

“Certainly it will come a time when it doesn’t make sense anymore to try to do it publicly, but I can still sing for myself, and sing for my friends, and sing for my family … I want to sing for as long as I have breath.”

~ Jessye Norman

For greater enlightenment...

-

Jessye Norman - A Portrait - When I Am Laid In Earth (Purcel)

-

Jessye Norman - Ave Maria (Schubert)

-

Jessye Norman - "Amazing Grace" (Sidney Poitier Tribute) | 1995 Kennedy Center Honors

-

Jessye Norman sings "Deep River" at Carnegie Hall

-

Spirituals in Concert - Jessye Norman and Kathleen Battle High Quality

-

Jessye Norman, opera singer - BBC HARDtalk

-

A Conversation with Jessye Norman

-

Jessye Norman Interview with Morley Safer