“The narrative of her photographs extends beyond a picture or a series of pictures to create a greater context for the artist herself within photography, womanhood and the African American experience.”

~ The Historymakers

On July 9, 1951, a baby girl was born to John and Elizabeth (née Hunt) Moutoussamy in Chicago, Illinois; they named her Jeanne. Elizabeth, whose family hailed from Arkansas, was an interior designer. John, who was of New Orleans and Guadeloupe, worked as an architect. An only child of passionate and accomplished professionals who were involved in the art and science of design, Jeanne was naturally exposed to their work. Inspired, her interests in drawing, painting and photography were encouraged by her parents.

When she was only eight years old, the Moutoussamy parents enrolled Jeanne at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she began her formal training in painting. In “Behind the Lens: Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe” by Joseph Montebello for BerkshireStyle.com, she described her parents’ belief and active support of her. In the article, she shared, ““My father was an architect who had studied with Mies van der Rohe and my mother was an interior designer. They instilled in me an interest in design. From the time I was eight years old, they sent me off to the Chicago Art Institute every Saturday. My mother would put me on the bus – same driver every week – and he would deposit me at the entrance. Those visits encouraged my creative thinking and helped to develop my creative eye.”

When she was a teen, she met photographer and art dealer Frank Stewart, who would become the official photographer for the organization, Jazz at Lincoln Center, at Lincoln Center in New York City. Jeanne Moutoussamy credited Stewart, who, according to the Montebello article, “introduced me to making photographs. I knew the work of Gordon Parks and Roy DeCarava and I was fascinated with the medium. Since I couldn’t paint or draw – although I loved doing it – I chose the world of photography.”

After graduating high school, Moutoussamy moved to the East Coast, attending the College of New Rochelle. After her freshman year, she transferred to the highly-lauded School of Art at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. It was during her junior year that she spent her terms on independent study in West Africa. She created three full-sized, photographic collections sourced from her time in seven West African countries!

(No copyright infringement intended).

This collection aided in her attaining a career position in the New York City office of WNBC of the National Broadcasting Company before she even completed her academic studies at The Cooper Union. Working in the graphic arts department, she soon earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in photography in 1975. By this time, she, as a Black woman, had firmly established herself as a journalist photographer in a field dominated by White males. Her work also extended to WNEW and PM Magazine.

However, in late October 1976, Jeanne Moutoussamy would encounter an experience that would forever change her life. Esteemed photographer and friend, Gordon Parks suggested that she photograph the United Negro College Fund (UNCF) Tennis Tournament created by tennis legend, Arthur Ashe, Jr. Intelligent, charismatic and handsome, he was the first Black man to win three Grand Slam singles titles. That victory led to numerous others, including being the only Black man to win the singles titles at Wimbledon, the U.S. Open and the Australian Open. He used his accomplishments to advocate for Blacks involved in all sports.

While Ashe was respected, admired and adored by many, their meeting was not typical. In the biography on Moutoussamy-Ashe at Encyclopedia.com, she referenced that there were so many people, especially women, around him, it was really a wonder that he noticed her. This is especially true, as a photographer tries to be as inconspicuous as possible in order to capture their subject(s). However, what really stood out to Jeanne was a comment he made. In the article, she recalled that he flirtatiously said, “‘Photographers sure are getting cuter.’ Moutoussamy-Ashe added: ‘I thought that was so bad. I thought it was cocky and I read it as a little sexist. It singled me out as a woman, which was totally against what I wanted to portray. I think he did it just to see what kind of reaction he was going to get. And he got one.’ Moutoussamy rolled her eyes in mock disgust and walked away. Later that same day, Ashe tracked her down at NBC and asked her out. On their first date a few days later, Moutoussamy brought him to her cubicle at NBC and showed him her portfolio. ‘He genuinely liked my photographs and the stories behind them … he got big points for that.’”

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

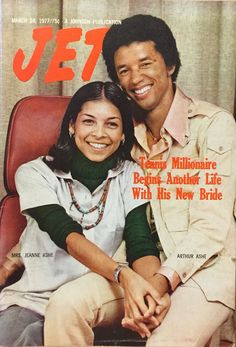

Four months later, Arthur Ashe, Jr. and Jeanne Moutoussamy married on February 20, 1977. They were married in a chapel in the United Nations of New York City and it was officiated by Andrew Young, the U.S. Ambassador for the United Nations and civil rights activist.

Wanting to retain her own identity, she elected to be known as “Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe”. Arthur Jr.’s support in her dreams, passions and abilities allowed her to leave MNBC to further pursue and grow professionally and personally. In the Encyclopedia.com biography, she praised Arthur, Jr., crediting his influence “that helped me to take my ideas and put them into book form … Often you feel you have the passion to do things, but to actually see it as a finished project has not always been my forte. Arthur’s confidence really brought that out in me. He gave me the comfort level that I could do that.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

Sadly, Arthur Ashe, Jr. suffered a serious heart attack in 1979. His health was in optimum conditioning for tennis. However, he had inherited cardiovascular disease from his parents, Arthur Sr. and Mattie, who had been diagnosed with it when she passed away from complications due to pre-eclampsia at only twenty-seven years old. Over the next several years, he underwent several operations to heal and appeared to be recovered four years later.

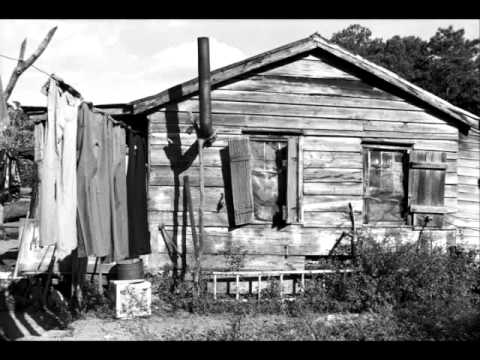

He resumed his work, which involved writing books, fundraising and sports commentating, as an advocate of Black athletes as well as civil rights. Jeanne’s artistic projects included authoring books, Daufuskie Island, A Photographic Essay (1982), about the Gullah community on the sea island in South Carolina, and Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers (1986), which discussed the immense contributions African American women made to the field of photography. Their mutual respect, admiration and love for each other prompted writer Laura B. Randolph in the October 1993 issue of Ebony to affirm that Jeanne and Arthur were “the quintessential Perfect Couple, the kind of lovers for whom the word ’soulmates’ was invented, a twosome whose love for one another could be seen – and felt -from afar.” Topping off this love was the adoption of a baby girl in 1986. They named her “Camera”, after one of Jeanne’s loves.

Tragically, in 1987, the Ashe couple discovered that Arthur, Jr. had contracted human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) after receiving a contaminated blood transfusion during his second heart bypass surgery in 1983. Wishing to protect their daughter from the negativity and social stigmatization associated with the virus’ status at that time, Arthur and Jeanne chose to keep this matter private within their family. However, a reporter from USA Today heard of Ashe’s illness and wanted him to confirm his condition for the breaking news story. Essentially blackmailed, the Ashe couple agreed to go public and held a press conference on April 8, 1992, where he spoke about his condition to the world. While condemning the nefarious tactics of those at the global newspaper, he also shared his relief in being able to be more public about his condition and how to positively impact change and work towards a cure for the illness. Arthur, Jr. bravely spoke about his condition, activism and the future, especially of Camera, which he knew he would not live to see. Breaking down in tears while mentioning their daughter, Jeanne courageously and beautifully completed his speech.

His activism included teaching others about HIV and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) which often accompanied the virus. He founded the Arthur Ashe Foundation for the Defeat of AIDS and the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health. After suffering a mild heart attack in September 1992, he addressed the immense need for AIDS awareness and funding for research at the General Assembly of the United Nations on World AIDS Day, December 1st. On February 6, 1993, Arthur Ashe, Jr. passed away from AIDS-related pneumonia; he was only forty-nine years old.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe continued her work, leading the foundations and working as a photographic journalist, while rearing Camera. Incredibly, Arthur, Jr. had completed the draft of his memoir, Days of Grace, one week before his passing. As a photographer and mother, Jeanne took numerous photographs of her husband with their daughter. This decision had been inspired by the loss Arthur, Jr. experienced when his mother passed. Only six years old at the time of her death, Arthur, Jr. had little memories of his mother and not even a photograph of her. Despite his illness, Jeanne’s images illustrated the vast joy and deep love the father and daughter shared with each other.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe decided, before his death, to publish a book featuring her husband and daughter. This decision was further supported when she shared an experience of their daughter with Ebony. In it, she recalled someone at Camera’s school told her that they saw Arthur on the television and that he had AIDS. Jeanne followed the painful recollection with the gentle power and wisdom of creating something so children could understand the goodness of life, even with an illness. Her “something” became the book, Daddy and Me: A Photo Story of Arthur Ashe and His Daughter, Camera, and was published in 1993. It was also the topic of an essay published in Life that same year.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe continued to write and exhibit her work in solo as well as group exhibitions. The last gift that she received from Arthur was a Hasselblad camera. In the story carried by Ebony, she confided that his physical passing did not cease their transcendent love. Praising her late husband for so many of his qualities, especially confidence, dedication, integrity and industriousness, she said, “I know it sounds cliched but I am really surrounded and sustained daily by the power of our love. When you’re in a relationship, I don’t think you recognize the everlasting power it can have. But I feel that now. And it is that, more than anything else, that has helped me to walk through this period.”

Her work has been featured in celebrated publications such as Associated Press, Black Enterprise, Ebony, Essence, The New York Times, Self and Smithsonian. She has premiered at the Leica Gallery in Hollywood; the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City; the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and also the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. She has exhibited in Europe, including The Excelsior in Florence, Italy and Herve Odermat in Paris, France.

An activist and philanthropist, Moutoussamy-Ashe continues her husband’s work and has served as the director of the Arthur Ashe Endowment for the Defeat of AIDS. She was a past trustee of her alma mater, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. Appointed in 1995 by President Bill Clinton, she was also an Alternate Representative of the United States to the United Nations.

(No copyright infringement intended).

According to her biography at “Art in Embassies” at the U.S. Department of State website, Moutoussamy-Ashe “has taught photography to both high school and college students, and she has been a guest lecturer at many educational and cultural institutions”. The recipient of numerous honors, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe received a Mayoral citation from the City of Chicago, her home city, in 1986. She has been gifted with two honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degrees. The first was from Long Island University in Long Island, New York in 1990 and the second was from Queens College in Charlotte, North Carolina in 2002.

In 2001, her book, The African Flower, was published and the documentary, Crucible of the Millennium, which she hosted, was featured on PBS. In 2007, she released Intimate Portraits: Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and in the following year, Essence gave her the Photography Literary Award. In 2011, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe’s book, Arthur Ashe: Out of the Shadow, was published.

“In the absence of finding the words to express feelings, I use photography as a response to what I feel. Even though the intent is not always to express a specific feeling what appears is what dwells within us and shapes our view of the world and ourselves.”

~ Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe