“She was a woman in a man’s world, and gently set about to change it, was creative, very well regarded, not bashful. She was looking for predictive activity for chemotherapeutic efficacy in vitro at a time when no one had good predictive tests.”

~ James F. Holland, M.D., professor of hematology, medical oncology, and oncological sciences, Mount Sinai School of Medicine

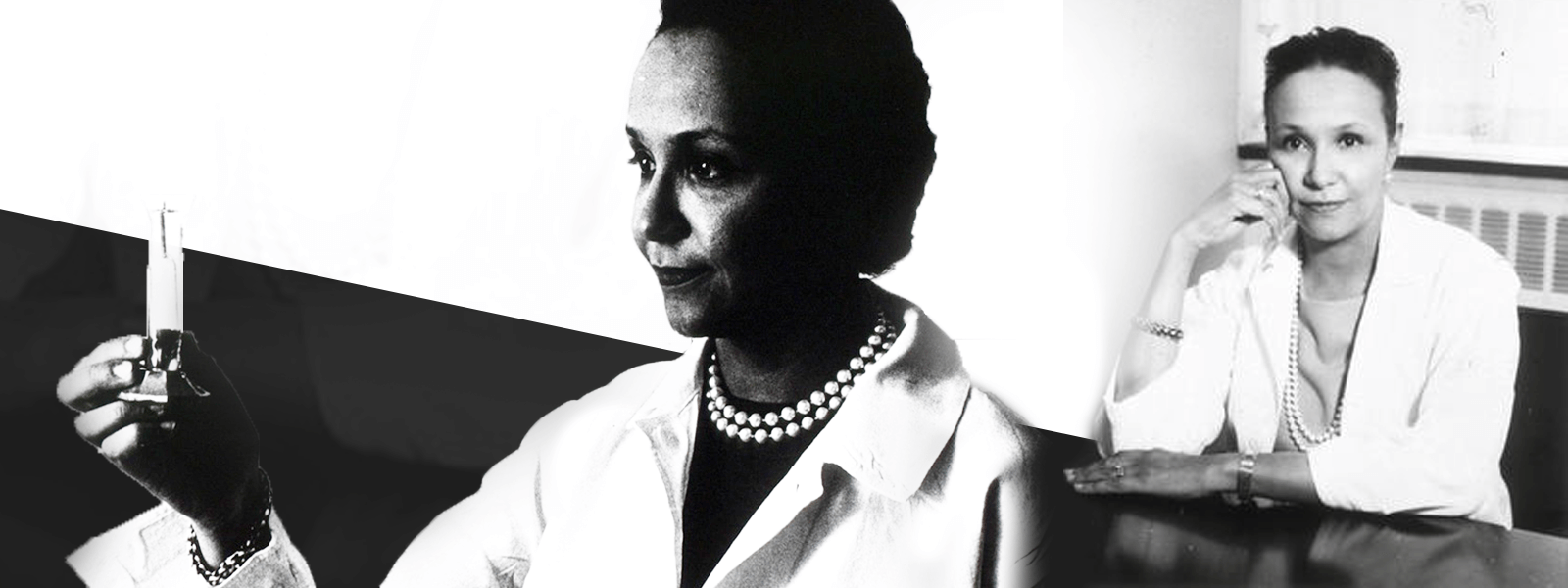

Born on November 20, 1919 in the Manhattan borough of New York City, Jane Cooke Wright was the oldest of two daughters born to Louis Tompkins and Corinne (née Cooke) Wright. Her mother was a professional educator and her father was among the first African-Americans to graduate from Harvard Medical School. He also was a graduate of Meharry Medical College of Nashville, which, founded in 1876, was the first medical school for African-Americans in the South.

Passion and activism, especially for African-Americans, in the medical field was of great interest to Jane’s family. Her paternal grandfather, Rev. Dr. Ceah Ketcham Wright had been a graduate of Meharry Medical College; her paternal step-grandfather, Fletcher Penn, was the first African-American to graduate from Yale Medical College; and her uncle, Harold Dadford West, served as the president of Meharry Medical College, 1952-66. All these men had to overcome tremendous odds of pervasive racial discrimination in order to attain their degrees and expertise.

In Women Pioneers of Medical Research: Biographies of 25 Outstanding Scientists by King-Thom Chung, it is reported that Dr. Louis Wright declared “… the American Medical Association has demonstrated as much interest in the health of the Negro as Hitler has in the health of the Jew.” Wright was highly lauded for his research in oncology and for his activism for racial equality in medical access and care with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), of which he served as chairman for nearly two decades. As the first African-American physician on staff of a non-segregated hospital in New York City, Wright established high standards for those who worked with him and inspired many, including his two children. His daughters, Jane and Barbara, would overcome racial and gender discrimination to become researchers and physicians.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Jane Cooke Wright was educated at the Ethical Culture School and the Fieldston School, from where she graduated in 1938. Upon completing her matriculation at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, where she was a pre-med student, she accepted a full academic scholarship from New York Medical College in 1942. Only one of the college’s few African-American students, she was elected vice president of her class and president of the Honor Society. After graduating with honors in 1945, Wright accepted an internship at Bellevue Hospital, where she served nine months as an assistant resident in internal medicine.

In 1947, Wright began her residency at Harlem Hospital, where she acted as chief resident. While in residency as a visiting physician, she also worked as a physician within New York City Public Schools. That same year, Wright married David Dallas Jones, Jr., an attorney who graduated Harvard Law School, and they had two daughters, Alison and Jane. In 1948, Wright would complete her residency at Harlem Hospital and the following year, she left her position within the metropolitan educational district to join her father, who established the Cancer Research Foundation at Harlem Hospital.

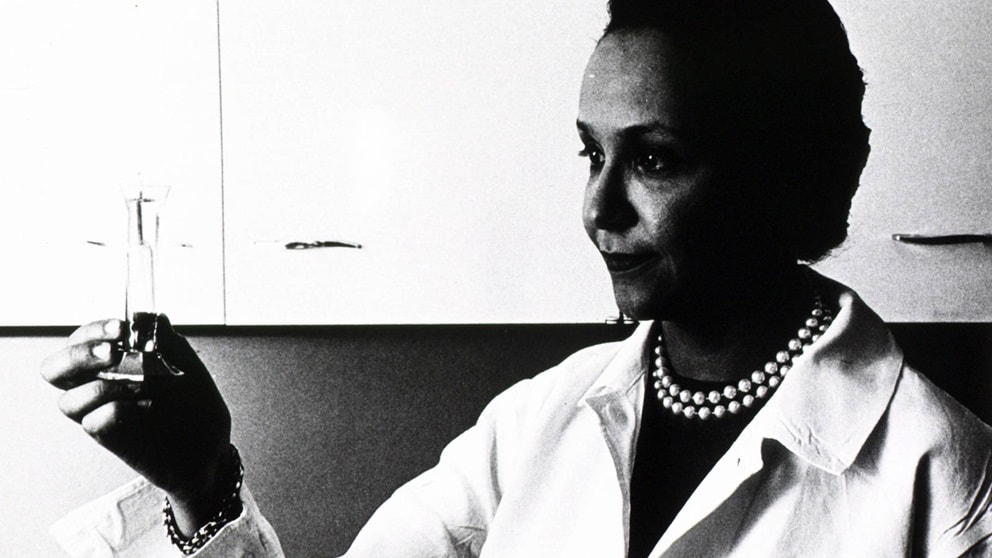

According to writer Sandra Swain in “A Passion for Solving the Puzzle of Cancer: Jane Cooke Wright, M.D., 1919-2013”, the Wrights “… were among the first researchers to test triethyl-enemelamine, a nitrogen mustard-like chemical synthesized during World War II, in patients with cancer. Remissions were observed in patients with sarcoma, Hodgkin’s disease, and chronic myelogenous leukemia, mycosis fungoides, and lymphoma. They also performed early research into the clinical efficacy and toxicity of folic acid antagonists, documenting responses in 93 patients with various forms of incurable blood cancers and solid tumors. Seven different folic acid antagonists were administered as single agents or in combinations, using various dosing and duration of treatment. Objective, although temporary, improvements were observed in 24 patients (including cases of sarcoma, leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease, metastatic breast cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, and metastatic cancer of undetermined origin) and 41 patients had subjective improvement. Among the 7 agents tested, aminopterin and amethopterin (methotrexate) appeared to be the most effective.”

The seminal research presented in a 1951 paper provided the first evidence of the efficacy of methotrexate against solid tumors. Methotrexate is presently used in treating various cancers, including breast, lung, osteosarcoma, leukemia, and lymphoma. Following the findings of this research, Dr. Jane Wright reported that methotrexate and Thio-TEPA could be utilized to supplement radiation and hormone therapy for patients who are diagnosed with advanced disseminated breast cancer.

As the director of the foundation, Dr. Louis Wright shifted its focus to investigate chemotherapeutic, or anti-cancer, chemicals and the physicians were highly interested in making chemotherapy more accessible. Because chemotherapy was highly experimental and considered as the last option to be undertaken when treating cancer in the late 1940s, the Wrights initially tested new anti-cancer agents on leukemia cells of mice. Eventually, they began testing the agents on leukemia cells of humans; they also experimented on cancers of the lymphatic system. The father-daughter doctors were conducting research during a time when guidelines for chemotherapy barely even existed. From their trials, the Wrights proved to be successful, as a number of their patients who participated in the trials had experienced remission. Throughout her career, Wright would continue to develop techniques to administer chemotherapy as well as examine, test and assess the relationship between patient and tissue culture response. The latter would lead to a more personalized approach to meeting patients’ medical needs.

In 1952, Dr. Louis Wright passed away at the age of sixty-one years old. His death stemmed from the lingering complications of tuberculosis, for which he was hospitalized (1939-42) during his service as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Medical Corp in World War I. Wright, who earned a Purple Heart, had joined the military after completing his medical school studies. Following his passing, his daughter was appointed as the new head of the Cancer Research Foundation; she was only thirty-three years old.

In 1954, Jane Cooke Wright joined the American Association for Cancer Research and was passionate about learning, sharing and disseminating information about the positive possibilities of cancer chemotherapy. The following year, Wright joined the New York University faculty as an associate professor of surgical research and director of cancer chemotherapy research at New York University Medical Center and its affiliates, Bellevue and University hospitals.

In 1964, several physicians, which included Wright, created a new medical society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO); their mission was centered upon patient-oriented issues that were specific to clinical oncology. Wright served as Secretary-Treasurer of this society from its beginning until 1967. Also, in 1964, Wright was appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to serve on the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke. Chaired by Dr. Michael E. DeBakey, results from the commission’s research prompted the creation of a national network of health centers to treat these three diseases. Additionally, Wright discovered that chemotherapy, via intra-arterial infusion through a catheter, could be diffused through many of the body’s major blood vessels.

Wright left New York University as she was highly sought by other institutions to conduct her research. Because her work continued to be groundbreaking, in 1967, she was, as Swain wrote, “… named professor of surgery, head of the Cancer Chemotherapy Department, and associate dean at New York Medical College, her alma mater.” Her latest professional advancements were also history-making. When the number of African-American women physicians practicing in the United States were only a few hundred, Dr. Jane Cooke Wright became the highest ranked African-American woman at a nationally recognized medical institution.

(No copyright infringement intended).

From 1966 until 1970, Wright was active on the National Cancer Advisory Committee of the U.S. National Cancer Institute. Under the National Cancer Act of 1971, members of the committee would be chosen only by a Presidentially-appointed, advisory board. She continued to pursue her research on cancer at the New York Medical College, where she developed a new, comprehensive program to study cancer, heart disease and stroke. While there, she also created a program to educate physicians about chemotherapy. In 1971, Dr. Jane Wright became the first woman president of the New York Cancer Society.

Wright’s expertise in oncology led her to become active on a global level. She took fellow oncologists to Europe and Africa and in 1957 and in 1961, Wright worked, respectively, in Ghana and Kenya, treating persons who were suffering from cancer. From 1973 to 1984, Wright acted as vice president of the African Research and Medical Foundation.

In 1987, Wright retired, after forty-plus years of being active in cancer research. The recipient of numerous awards and honors, including the Spirit of Achievement Award from Albert Einstein College of Medicine, she authored one-hundred and thirty-five scientific papers and contributed to nine books. The American Association for Cancer Research created a lecture position in honor of Wright.

On February 19, 2013, Dr. Jane Cooke Wright passed away at the age of ninety-three years old. Fortunately, before her passing, the Jane C. Wright, M.D., Young Investigator Award was created by ASCO and the Conquer Cancer Foundation to honor the contributions of Wright to the field of oncology in 2011. The award is gifted to early-career physicians who model the excellence that Jane Cooke Wright exemplified. Martin J. Murphy, chair emeritus of the Conquer Cancer Foundation Board of Directors, spoke to the greatness of Wright, professionally and personally, when he affirmed, “They are following in her phenomenal footsteps, with tenderness toward patient care, with rigor towards scientific investigation, with focus that is always external and always on the patient.”

“The ultimate goal was to bring into the specialty a greater number of talented individuals who shared the goal of winning the battle against the ravages of cancer.”

~ Jane Cooke Wright