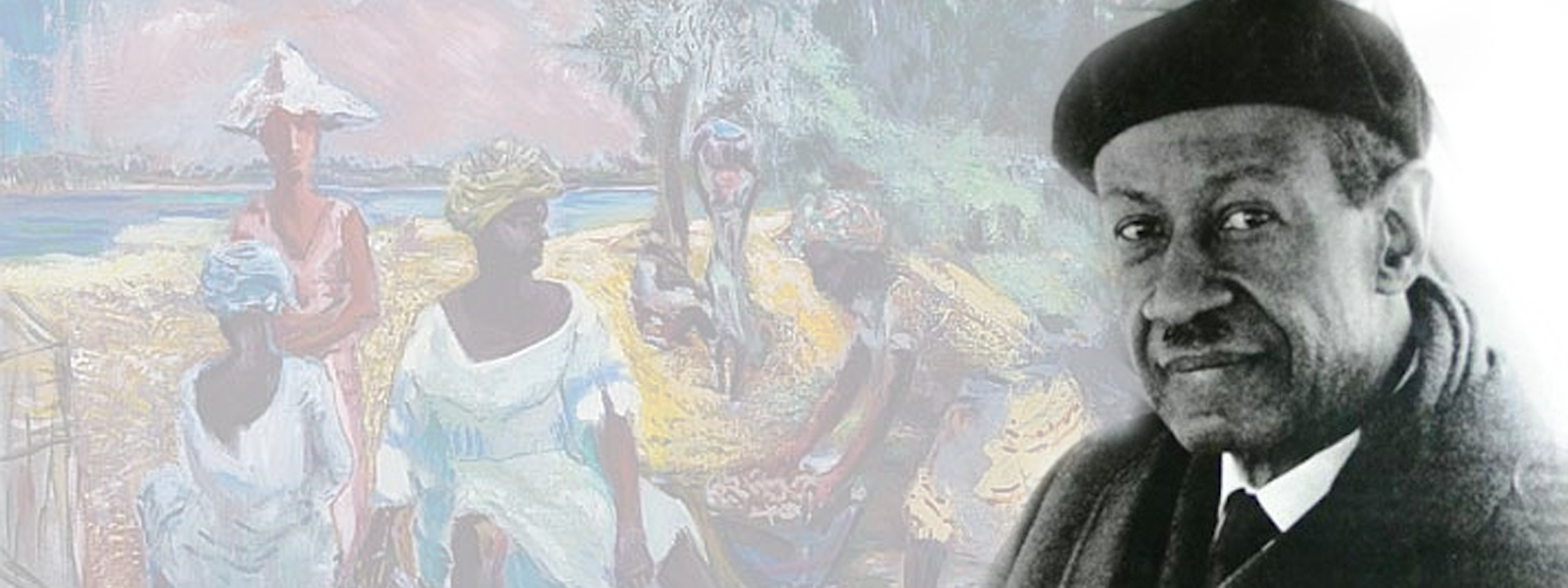

“The multi-talented (James A.) Porter was an artist, scholar, educator, and mentor. He is recognized as the first African American art historian; his 1943 publication Modern Negro Art, is the earliest comprehensive treatment of the contributions of artists of African descent to American art and culture.”

~ Gwen Everett, Author, art historian

On December 22, 1905, in Baltimore, Maryland, James Amos Porter was born to John and Lydia Porter. His parents were professionals who held significant status in their community. His father, a minister, was prominent in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and his mother, an educator, worked within the segregated public-school system.

The youngest of eight children, he matriculated schools in Washington D.C., graduating at the top of his class from Armstrong Manual Training School in 1923. James also had excelled in academics. During that time, he had become interested in art, significantly painting, which was introduced to him by his older brother, John. His efforts in education and art were admired by James Herring, who headed the art department at Howard University, a historically Black university in Washington, D.C.

Underneath the tutelage and mentoring of Herring, Porter entered Howard University in 1923 to study art history, drawing and painting. In 1927, James A. Porter earned his Bachelor of Science degree, graduating with honors from Howard. He was immediately hired to join its faculty to teach drawing and painting.

In 1928, James A. Porter submitted a painting of his to be shown; it was the first time his work was featured in a major exhibition. Afterward, his art would be shown in solo and group exhibitions, domestically and internationally.

Throughout his life, Porter continued to grow in learning, taking courses at Teachers College at Columbia University in the City of New York, the Art Student League in New York City, and the Institut d’Art et d’Archeologie, at the Sorbonne in Paris, France. His opportunity to study at the Institut in 1935 was made possible from a fellowship of the Institute of International Education. James A. Porter received his Certificat de Presence from the Institut d’Art et d’Archeologie in 1935 and earned his Master of Arts in art history from New York University in 1937. While at the Art Student League, Porter studied with the renowned painter, Dimitri Romanovsky and at the Institut d’Art et d’Archeologie, he researched medieval archeology.

His time in New York City was primarily spent undergoing research to create. He discovered Robert S. Duncanson, an accomplished African-American artist who lived during the Civil War period. His works and contributions had been obscured, practically omitted, from history. This omission prompted him to further research other African-American artists who, like Duncanson, were also neglected.

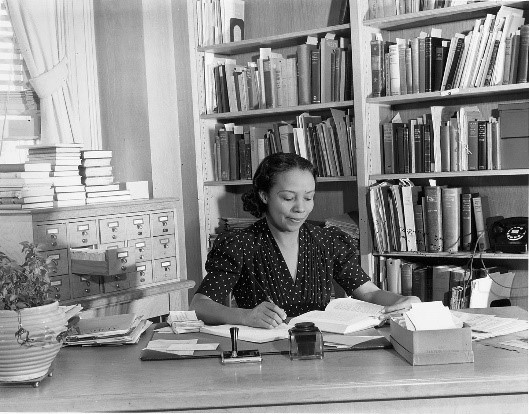

Porter sought to conduct his research at the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library (presently known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture). There, he met a librarian, Dorothy Burnett, who shared his interests. Their connection grew and on December 27, 1929, James and Dorothy were married; they would have a daughter, Constance. Dorothy, who would be integral to her husband’s research, later served as the director of the Moorland Foundation, which is presently known as the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, at Howard University. Her guidance, significantly on African American artists, has been essential in the center developing into one of the largest and most comprehensive repositories of Africa Diaspora culture and history in the world.

This image is sourced from United Against Racism (No copyright infringement intended).

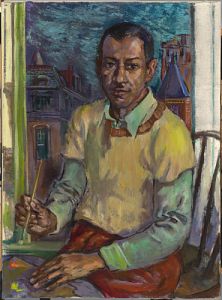

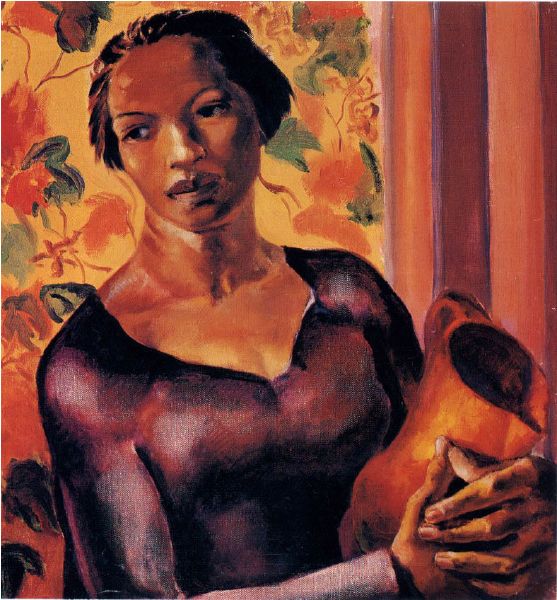

As he became prominently known for his still lifes, charcoal drawings, figure studies and portraits, especially elegant oil portraiture of African-Americans, James A. Porter began to submit his art to the William E. Harmon Foundation for exhibition. In 1929, he earned an honorable mention and in 1933, he was awarded the Arturo Schomburg Portrait Prize for his piece, “Woman Holding a Jug”. This award allowed him to further extend his scope of presentation, as his works would be featured in exhibitions, such as The Negro Artist Comes of Age, The Negro in American Art and Two Centuries of Black American Art; 1750-1950. Porter’s art has been exhibited in esteemed galleries including the Baltimore Museum of Art, Barnett-Aden Gallery in Washington, D.C., the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Detroit Institute of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

This image is sourced from Pinterest (No copyright infringement intended).

While in France, Porter poured over collections of African art and became acquainted with expatriate West Africans, including François “Féral” Benga, a dancer and model of Senegal. After receiving his certificate in Paris, Porter was awarded a stipend from The Rockefeller Foundation. The stipend would be used to support his travels in Belgium, Germany, Holland and Italy. He extended his time in Europe, as per the biography on James A. Porter by Smithsonian American Art Museum website, in order, “to make a first-hand study of certain collections of African Negro arts and crafts housed in important museums of ethnography.”

This extension would be important in supporting his stances against critics, such as African-American philosopher and editor, Alain Locke, also of Howard University and considered to be the “Father of the Harlem Renaissance.” Locke felt that African-American artists needed to seek inspiration in their African heritage, whereas Porter felt their American heritage was primary. In 1937, Porter held strong to his position in an article published by Art Front.

In the biography of James A. Porter featured on The Johnson Collection website, it is detailed, “His abiding interest in African American art history formulated the basis for his graduate thesis, which was awarded in 1937. This paper formed the basis of what became his landmark text, Modern Negro Art, published in 1943. The book was immediately hailed as an unprecedented, comprehensive, and essential reference on African American art and remains a classic today. Some of Porter’s arguments ran counter to those of other key Black intellectuals. For instance, writing in the chapter entitled “New Negro Art,” he eschewed Alain Locke’s position that African-American artists should “exploit the ‘racial concept’ and instead believed that African-American art must be approached as integral to the broader narrative of American art. Porter also disagreed with W.E.B. DuBois on the use of abstraction, praising artists who continued to opt for figural representation.”

His work as a historian and scholar of African-American art is where James A. Porter would make his greatest contribution. His research on Black artists was the foundation for his thesis. Initially appearing in the Art in America, his findings were the first account of African-American artists to be published in a mainstream art journal.

Most significantly, his research led to the publication of Modern Negro Art in 1943. Groundbreaking, the book would be the first to detail the complex and comprehensive history of African American art. It also posited African American art within the context of American art history. Porter’s Modern Negro Art is still heralded as definitive.

For the academic year, 1945-1946, James A. Porter went on sabbatical from Howard University. Having received another stipend from The Rockefeller Foundation, he visited cultural institutions in the Caribbean, significantly, Cuba and Haiti. His research formed courses in Latin American art that would be taught at Howard University. During this time, Porter also painted portraits of daily life and his most famous painting was The Cuban Bus.

Continuing to educate others outside the academy about African-American artists, Porter composed an article on Duncanson that was published in Art in America in 1951. Upon the retirement of Herring in 1953, Porter assumed the position as the department chair, which he held until his passing, and head of the Art Gallery. At the gallery, the works he exhibited highlighted the work of African-American, Cuban and Haitian artists.

In 1955, he was appointed a fellow of the Belgium-American Art seminar, studying Dutch and Flemish art from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. His final educational trip overseas was during the 1963-64 academic year. Sponsored by a grant of the Evening Star, a newspaper in Washington, D.C., the Porters toured West Africa and Egypt. The West African countries they visited included Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo. His research, which consisted of museum visits, personal interviews with artists and photographing more than eight-hundred works of art and architecture, became the source of courses on African art and architecture that would be taught at Howard University. Porter also created a series of paintings, twenty-five in all, whose subject matter was rooted in West African themes. Becoming more expressionistic in his creations, Porter, according to The Black Renaissance in Washington website, “sought to capture the rhythmic accents of African life, the changeful moods of color and atmosphere.” Although his art often contained African themes, it was not until this visit to West Africa that his works directly referenced Africa. His series debuted in The Art Gallery of Howard University in 1965.

This image is sourced from Pinterest

(No copyright infringement intended).

That same year, James A. Porter was selected as one of twenty-five art educators ranked as the best in the United States by the National Gallery of Art. The gallery, which was celebrating its twenty-fifth anniversary, was honored by President Lyndon B. Johnson and First Lady Claudia “Lady Bird” Johnson, who awarded the artists. In 1967, Porter curated an exhibition, Ten Afro-American Artists of the Nineteenth Century. It featured the works of artists such as sculptor Edmonia Lewis and Duncanson, whose work first inspired him to research and record the accomplishments of Black artists. He continued working as a painter, draftsman, educator and African-American art historian until his death.

On February 28, 1970, James A. Porter passed away; he was sixty-four years old.

James A. Porter is best remembered for his trailblazing work in African-American art history. His artwork is featured in institutions throughout the United States, including the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the world. The book, The Black Artist, that he had been writing was never completed.

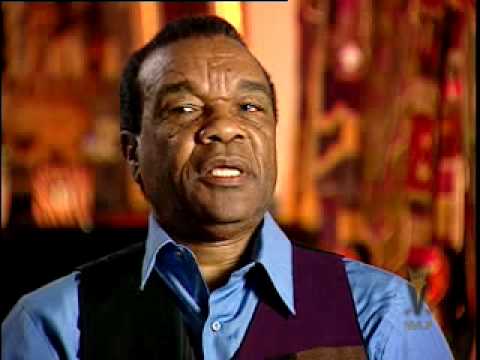

As an educator and mentor to generations of learners, in 1990, Howard University created an annual academic conference, the James A. Porter Colloquium, in his honor. It features leading and emerging scholars and artists in African-American art history, the field he helped found. Participants include students of Porter, such as David C. Driskell and Tritobia Hayes Benjamin, as well as curators, scholars and artists like Lowery Stokes Sims, Michael Harris, Deborah Willis and Samella Lewis, the first female African American to earn a doctorate in fine arts and art history.

In 2010, Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, acquired papers of James A. Porter from Swann Galleries in New York City. The auction house made available research material, such as art books, exhibit catalogs, flyers and photographs, for purchase. The collection of papers that the university obtained contained letters from every significant African-American artist, including Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett and Lois Mailou Jones, from the 1920s until his death.

Regarding his extensive legacy, Jeffreen M. Hayes on the website of the James A. Porter Colloquium praised, “James A. Porter left a cultural and educational legacy to those passionately involved in the area of African American art. The drive to explore and firmly document artists of the Diaspora continues today. Porter’s artistic and historical work provides a solid foundation in which current and future scholars can build upon. Many scholars owe Porter for the inspiration to probe the depths of African American visual culture and attest to its significance to American culture.”

This image is sourced from Facebook (No copyright infringement intended).

“You can’t help painting when you’re in Africa – the skies, the red earth, the verdure and the dress of the people – all of them reinforce one’s feeling for color.

~ James A. Porter