“He was just an indomitable advocate for Black people, whether it was getting them to vote, getting them on juries, desegregating the schools, having a Black Santa in the mall, getting Black people to run for office. So over the course of his lifetime there’s certainly no one more important in terms of Black empowerment in Selma than J.L. Chestnut, Jr.”

~ Julia Cass, author and journalist

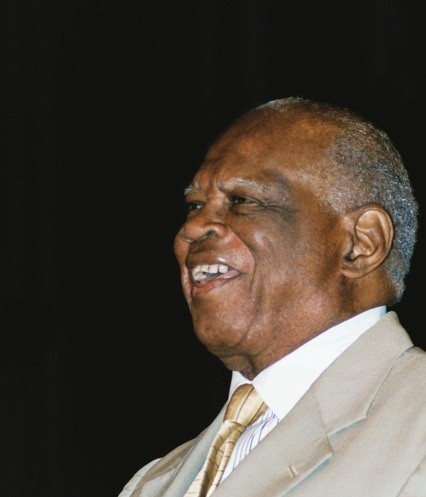

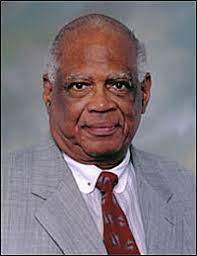

J.L Chestnut, Jr. was born on December 16, 1930 in Selma, Alabama. According to his autobiography, Black in Selma: The Uncommon Life of J.L. Chestnut, Jr., co-authored with Julia Cass, the initials were his actual name. His father, J.L. Sr., was given the name by his mother who named him after a White banker who she had admired. J.L. Sr. co-owned a grocery with his two brothers and his wife worked as an elementary school teacher.

An accomplished student, he attended segregated schools in Selma. The obvious disparity of resources available to those of White students and lack of opportunities afforded J.L. Jr. and other Blacks infuriated him. According to his account, he was encouraged by a childhood mentor, John F. Shields, to enter the field of law in order to combat these inequities.

After graduating high school, J.L. Chestnut, Jr. attended Dillard University, a private, historically Black university in New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1953, he completed his studies, graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration. Soon after, he matriculated law school at Howard University, an esteemed, historically Black institution of higher learning located in Washington, D.C. At this time, the Civil Rights era had been underway. Chestnut, Jr., affectionately known as “Chess”, was heavily influenced by those attorneys, such as Charles Hamilton Houston, Thurgood Marshall Pauli Murray and Constance Baker Motley, at Howard who were involved with the battle to dismantle segregation and racial discrimination.

After graduating from Howard University School of Law, J.L. Chestnut, Jr. returned to his home city to practice law. Becoming Selma’s first Black attorney in 1958, he founded his own law firm. This firm soon expanded to, ultimately, become Chestnut, Jr., Sanders, Sanders and Pettway. Black attorneys Henry “Hank” Sanders, who became a Senator (D-AL) in 1983, and his wife Faye, were recruited by Chestnut, Jr. to join his firm after their graduation from Harvard Law School.

His work in Selma spanned more than five decades. He fought diligently for African-Americans to have a better quality of life. This fight involved integrating the field of law; gaining and protecting voting rights; filing civil rights cases for Blacks to be included on juries; de-segregation of public facilities and laying the foundation for the march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965. He represented both ordinary and now-famous persons, such as Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., active in civil rights activities.

In a radio interview, “J.L. Chestnut, Campaigning for Rights in Selma” for National Public Radio, Chestnut, Jr. discussed his relationship with King, Jr. Speaking with hostess Terry Gross, he recalled, “I had been somewhat ambivalent about all of the Civil Rights leaders there. I felt that what they were saying was directed more at the masses than at me. After all, I had two degrees, too, and I was educated, and Martin had views which ran counter to everything I’d learned in law school. For an example, he insisted that he had a high moral right to disobey an unjust law, and he would make the determination when the law was unjust. That is not what I learned in law school. That was not what I believed in. I felt that you go to court to get a law declared unconstitutional. I wasn’t quite sure about all this unjust businesses. That’s not the terminology that lawyers used. In addition to that, Martin was always trying to get me to give up my weapon (gun) and calling me a man of little faith. And I was telling him that, you go ahead and preach to the masses, but I’m not paying you any attention. I’m going to keep my weapon because it can bark here and bite way down the street, and Martin would laugh. But I knew that his presence in Selma meant that more people like my mother, middle class Blacks, would become involved, that Martin’s presence gave a legitimacy to the movement that it otherwise would not have. Also, as long as he was involved, important and powerful White people in Washington would be watching. So he meant everything to the movement.”

A brilliant and charismatic attorney, J.L. Chestnut, Jr. was admired by many, including George Wallace, who he met before he became governor of Alabama. Wallace was renowned at one time for his extreme racist rhetoric and segregationist acts. However, Chess often shared that Wallace was the most liberal judge he ever stood before and that he was the first judge to ever call Chestnut, Jr., “Mr.”

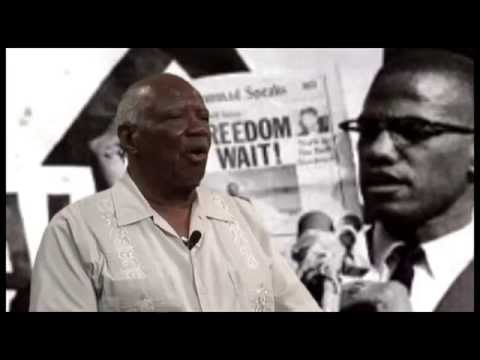

Perhaps one of J.L. Chestnut, Jr.’s greatest acts was his involvement in the history-making demonstration held on March 7, 1965. Approximately 550 non-violent protestors intended to march from Selma to Montgomery. It was led by John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Rev. Hosea Williams of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) while Bob Mants of SNCC and Albert Turner of SCLC followed. The purpose of the march was to bring awareness to the overt and pervasive discrimination, neglect and segregation experienced by African-Americans and other “third class” citizens and to exercise their rights, including to vote. When the demonstrators attempted to cross Edmund Pettus Bridge, Alabama state troopers viciously attacked the protestors and even used tear gas. Ultimately, fifty marchers were treated for injuries but seventeen, including Lewis, were hospitalized. Chestnut, Jr. provided legal defense for those involved.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In “J.L. Chestnut, Jr., Early Leader in Civil Rights Movement, Is Dead at 77”, in The New York Times, journalist Bruce Weber wrote of John Lewis’ friendship and respect for Chess. In the article, Lewis, who later served as a Representative (D-GA), reminisced, “I don’t know what would have happened to us in Selma if it wasn’t for Chestnut … Selma was a vicious place, vicious. I don’t know how he survived there, I really don’t. He used the law to help liberate the Black folk of Alabama. He was a lawyer, but he was also a foot soldier. He was a brave and courageous man.”

The brutality and illegality of the treatment by law officials at this event, which became known as “Bloody Sunday”, was shocking and numbing. It gained international attention as those around the world questioned how a democracy such as the United States could treat a group of its citizens so brutally, especially those who were protesting peacefully!

Two weeks later, King, Jr. led the march to completion. The series of marches from Selma to Montgomery, including Bloody Sunday, were integral in sparking political change within America, such as the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

J.L. Chestnut, Jr. continued to advocate for justice. In the NPR interview with Gross, he expressed, “I am really astounded at the progress we had made, but I’m even more astounded at the progress we haven’t made. It’s like talking to the White people in Selma, who were always telling me, said, look how far you’ve come in no time at all. And I will always say, that’s true, but look how far we have to go. But I’ve had a chance to view (the progress made) for the first time because of this book.”

His many achievements, according to “J.L. Chestnut, Jr., 77, was First Black Lawyer in Selma, Ala”, carried in the Press-Telegram, included “defending Blacks in major voter fraud prosecutions brought by the Justice Department in west Alabama in the 1980s. He joined other Black leaders in a meeting with then-Attorney General Edwin Meese in 1985 to complain about the department’s handling of civil rights issues. Later he was a lead attorney in a class-action lawsuit that thousands of Black farmers filed against the U.S. Department of Agriculture for regularly denying subsidies and other assistance to them because of their race.” In 2000, his firm won an almost $1 billion settlement against the Department of Agriculture for their decades-long practice of racial discrimination. Chestnut, Jr. led the appeals for thousands of Black farmers who had been denied compensation in the federal settlement.

His law practice, which included the Sanders with whom he worked for thirty-seven years, became the largest Black law firm in Alabama in the 1990s. Chestnut, Jr. was an original member of the Board of Directors of the Alabama Capital Representation Resource Center; this center is presently known as the Equal Justice Initiative. He also wrote a column, “The Cold Hard Truth”, featured in the Green County Democrat, a weekly newspaper published by founders John and Carol Zippert. John Zippert, a member of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, a collective that organizes cooperatives and works with Black farmers, shared that Chess’ articles were a significant reason that many people bought his publication.

(No copyright infringement intended).

On September 30, 2008, J.L. Chestnut, Jr., passed away at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Birmingham, Alabama. His death resulted from kidney failure which arose from an infection that developed after a previous surgery. J.L. Chestnut, Jr. was seventy-seven years old.

He was survived by his wife, Vivian, of fifty-six years and their six children. He was greatly admired by many including dear friends, Dr. Richard Arrington, Jr., the first Black mayor of Birmingham; Rev. C.T. Vivian and writer Julia Cass. With his assistance, the author wrote a murder mystery set in a small fictional town in Alabama in 1964. In the Press-Telegram article, Cass spoke of their friendship, crediting him with teaching her that there is a “White point of view and a Black point of view.” In that article, she also praised J.L. Chestnut, championing that he “was really a giant as far as fighting for Black voting and legal rights for half a century.”

“I have had the chance to look back over thirty years. And I’m not displeased with what I see.”

~ J.L. Chestnut, Jr.