“You have done your people and mine a service … What a revelation of existing conditions your writing has been for me.”

~ Frederick Douglass, activist, orator, statesman and author

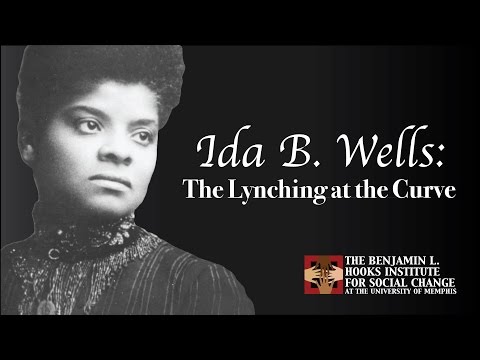

In Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16, 1862, a baby girl was born to James and Elizabeth (née Warren) Wells; they would name her Ida Bell. James’ father, who was White, had brought James to Holly Springs to be a carpenter’s apprentice; his mother, Peggy, was a Black woman who, as a child, had been sold from her family.

Because of their race, the Wells family was enslaved and considered property of the Bolling family. On the plantation, her father worked in carpentry and her mother labored in cooking. When the Civil War ended in 1865, soon after, slavery throughout the United States was made illegal. During the Reconstruction period, the Wells became highly active in the Black community. They emphasized to their eight children the imperative importance of involvement in and commitment to Black activism, especially politically, economically and educationally.

James, a member of the Republican Party, was fired by his former master of the Bolling plantation when he cast his own vote contrary to what Bolling demanded. Locked out from the carpentry shop, Wells bought his own tools and began his own carpentry business. He was also a member of the Freedman’s Aid Society, an organization started by the American Missionary Association in 1861 that assisted, from an educational vantage, where Blacks newly freed from slavery. The association set up schools in the South that those Blacks could be educated to become teachers, nurses and other professionals.

Additionally, James Wells helped establish in 1866 what would be chartered as Shaw University in 1870. A private, liberal arts college, it would be renamed Rust College in 1892 and is presently one of only ten historically Black colleges and universities, founded before 1868 that is still in operation. Rust College, as the second oldest private college in Mississippi, is the oldest of the eleven historically Black universities and colleges associated with The United Methodist Church.

Ida was a very bright girl who loved to learn and read, which she often did to her father and his friends during the evenings. She received her early education at Rust College. However, when she was away visiting her grandmother, Peggy, who lived near Holly Springs, an epidemic of yellow fever struck her home city. In 1878, Ida lost both her parents and a baby brother to the deadly virus. In order to keep her immediate family intact, Ida took custody of her siblings. Only sixteen years old, she accepted a teaching position in her local community school. While Ida worked during the day, her paternal grandmother, Peggy Wells, took care of the children.

After the passing of their grandmother and a sister, in 1883, Ida and her siblings moved to Memphis, Tennessee to live with their aunt, Fanny. There, she accepted a position to teach in Woodstock. At this time, she resumed her academic pursuits, taking courses at Fisk University and Lemoyne-Owen College, both historically Black academic institutions in, respectively, Nashville and Memphis. She joined a lyceum where she and other members met to exchange ideas, debate and read expository writings and poems. The organization created their own journal and Ida later served as its editor. Her essays, which covered religion and politics, appealed to both male and female readers. As she grew popular among readers, her influence grew quickly, drawing invites for numerous social gatherings and even being covered in Memphis newspapers.

In May 1884, Ida B. Wells sued the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad, a train car company in Memphis, for unfair treatment based upon racial discrimination. She bought a ticket for travel in a first-class railroad car. However, the conductor demanded that she move to the smoking car, where Blacks were forced to sit. At this time, private and public businesses could still choose to racially segregate its customers and their discrimination was supported by the 1883 U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling against the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Upon her refusal to move, the conductor and two men dragged her out her paid-for seat. Frightened and upset, she refused to sit in the smoking car and chose to get off the train. She wrote about her ordeal in an article for The Living Way, a Black church weekly paper. She also hired an attorney to sue the railroad, hoping it would set a precedent for defeating Jim Crow laws in the United States. She, ultimately, in December 1884, won her case when the judge ruled against the railroad train car company and it had to pay Wells $500 compensation. She felt elated in that she had fought hard to defend her rights and was victorious.

However, the decision was made at a local level and the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court. In 1887, the state supreme court reversed the decision of the Memphis circuit court, even citing that Wells’ intent was to harass and she was ordered to pay court costs. She felt great disappointment for her loss but, as Phillip Dray wrote in Yours for Justice, Ida B. Wells: The Daring Life of a Crusading Journalist, “… most of all, Ida was heartbroken for all the Black people who would continue to live under Jim Crow laws. ‘I had hoped for such great things from my suit for my people’ … she wrote in her diary, “and just now if it were possible (I) would gather my race in my arms and fly away with them.’”

Despite the ruling, Ida B. Wells was not defeated. She continued to teach elementary school but her activism continued to grow. Under the pen name of “Iola”, she continued to discuss race, education, religion and politics in articles she wrote for The Living Way and accepted a position as editor of the Evening Star, a newspaper in Washington, D.C. Called “The Princess of the Press” by her readers, she, in 1889, became a partner and editor in a local newspaper, the Free Speech and Headlight. The Memphis newspaper was started by Reverend Taylor Nightingale and headquartered at the Beale Street Baptist Church. Owned by J.L. Fleming, the Black publication would later be renamed the Memphis Free Speech.

In 1891, Ida B. Wells was fired from teaching within the Memphis public school system because her articles criticized the conditions of schools and the gross inequity of education given to Black students within its district. Although she was upset, she continued to advocate for equality for Blacks, especially women, and the dismantling of the Jim Crow system.

While working at The Living Way and the Free Speech and Headlight, she began traveling to gain more supporters of her work and platform, which included her newspaper. She attended conferences for Blacks involved in the journalism industry and was elected to serve as secretary of the Afro-American Press Convention. At these meetings, she met influential individuals such as T. Thomas Fortune, who was the co-owner of a respected Black newspaper, New York Age. She traveled throughout Tennessee, Arkansas and Mississippi to promote the Free Speech, which by this point, had been printed on pastel pink paper. The distinctive hue made it even more popular and within a year, subscribers grew from 1, 500 to greater than 4, 000!

In 1892, Wells was away from Memphis on a speaking tour when she received the news that her good friend, postman Tom Moss, had been murdered. Quickly returning to Memphis, she discovered that Moss, and two of her other friends, Calvin McDowell and Will Stewart had been lynched. In 1889, the three Black men, as part of a 11-member collective, started their own grocery store, People’s Grocery, in “The Curve” neighborhood of South Memphis. Because of its respect and shopping experience provided to Black consumers, the store was competition for a White-owned store. The White owner, William Barrett, and his supporters harassed and threatened Moss, McDowell and Stewart on numerous occasions that their business was to close. When the three owners of People’s Grocery tried to seek protection from the Memphis police, law enforcement did not protect them.

The March 2nd, 1892 incident that precipitated the attack on the men allegedly grew from two young boys who fought over a game of marbles. Armour Harris, who was Black, was defeating Cornelius Hurst, who was White. When Hurst’s father jumped in and began beating Harris, Will Stewart and Calvin McDowell came to the defense of Harris. As Blacks and Whites joined in the fight, Barrett claimed he was clubbed by Stewart.

On the evening of March 5th, six armed White men, including a county sheriff and recently-deputized plainclothes civilians, blocked the front and back entries of the grocery store. Invading the store, the Blacks inside fired their guns in response, not knowing who these men were or their supposed intent to inquire about Will Stewart. Ultimately, Moss and his two business associates were arrested and jailed while no Whites were even charged.

Hundreds of White civilians, who had been deputized, conducted a house-to-house search for Blacks involved in the “conspiracy” supporting People’s Grocery. Forty Black people, including the young boy, Armour Harris; his mother, Nat Trigg; and Tom Moss, were arrested. Although there were accounts that Moss had not seen what happened at the grocery store, it is believed that he, as a professional (a postman) and president of their store’s collective, was named by envious Whites to be the “ringleader”. White newspapers tried to justify the persecution of Moss because he was “insolent” and “uppity”.

On March 9th, seventy-five armed, White men, in black masks, surrounded the Shelby Country Jail. A lynch mob of nine stormed it, dragging the Black men from the cells, and lynched them at a Chesapeake & Ohio railroad yard. The murders, which were extremely vicious and violent, were detailed so harrowingly in White newspapers that it is obvious that White reporters had been contacted prior in order to witness the lynching.

After the lynching of Moss, McDowell and Stewart, Whites were given carte blanche by Judge Julius DuBose, a former soldier of the Confederacy, to essentially terrorize the Black citizens of The Curve. Whites assaulted Blacks, even shooting at them, and vandalized People’s Grocery. The store would soon be sold at one-eighth of its value to William Barrett, the White proprietor of the competing store and who alleged that Will Stewart attacked him.

They lynching made the front pages of the March 10th issue of The New York Times. These heinous acts, and all its factors, completely contradicted the “New South” image that Memphis was said to have portrayed. Although the community knew who killed the three men, no one would identify the guilty parties. Accordingly, no one was ever punished for the murders of Tom Moss, Calvin McDowell and Will Stewart.

The lynching enflamed many across the United States and people from all over the nation attended the funeral services. Wells tried to be a comfort to the men’s survivors, especially Moss’ wife and children, to one of whom she was a godmother. Impassioned by Moss’ dying words, Wells implored Blacks to leave Memphis, whether on train, wagon or foot, and settle in the American West. She hoped that they would escape the horrors of racial discrimination, lack of justice and lynching. She, as quoted by Dray, wrote in the Free Speech that, “There is therefore only one thing left that we can do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by White persons.” Her words indeed had power, as the lynching would provoke the emigration of more than six thousand Blacks from Memphis to western states.

In a personal protest to this massive injustice, Ida B. Wells actually remained in Memphis and began an anti-lynching campaign. As an editor, she researched, wrote and published articles against lynching in her newspaper and other Black-owned publications, including for Fortune’s New York Age. She lectured throughout the United States and England on the horrific topic of lynching and organized anti-lynching societies. Her research, based upon primary documents, police records, personal interviews and data, led Wells to conclude that Whites’ use of lynching against Blacks was to destroy Black economic, social and political progress.

In 1892, Wells published her research in a pamphlet, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. Her conclusions of the violent phenomena violating the Black community was all too often sourced in White Southerners’ allegations of disrespect towards them and false charges of “rape” of White women by Black men. In 1895, she published The Red Record (1895), which described in greater detail the violent practice of lynching since the passing of the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 as well as the trials Blacks faced in the American South since 1861. The 100-page pamphlet illustrated the alarming development of lynching in America, which had begun to peak in 1880.

Ida B. Wells continued to write and publish essays against lynching, capturing the attention of Northerners, who had little idea of lynching or the nefarious reasons behind it. Acknowledging that Whites would continue to utilize lynching to promote their own economic self-interest while halting Black economic development, she still sought support among Whites, domestically and internationally. She refuted claims that Black men had to be murdered in order to protect and retain the virtue of White women, citing that the rape of Black women by predatory White men was much more prevalent. Because of the domestic terrorism, Wells concluded that Blacks should use armed resistance as a defense. In her Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, she stated, “A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every Black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give.”

Themes in her editorials infuriated some Whites. In 1892, an enraged mob of White men stormed into the offices of the Free Speech, smashing all the office furniture and destroying equipment. They left behind a note threatening her and Fleming’s life. Wells had not been there, as she was in New York, visiting Fortune. As the editor of the New York Age, he invited her to write for the publication, which was one of the most popular Black newspapers in America. She wrote an in-depth article on lynching, the destruction of the Free Speech offices and threats on her and Fortune’s lives. The issue that featured her article on lynching sold greater than ten thousand copies nationwide.

In 1893, Ida B. Wells, alongside African-American leaders such as Frederick Douglass, protested the World’s Columbian Exposition for its exclusion of African-Americans and negative portrayal of the Black community. She so impressed Douglass that he would serve as a great mentor to her and, at times, financial sponsor of her work. She published The Reason Why the Colored American is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition: The Afro-American’s Contribution to Columbian Literature, which featured contributions of Wells, Douglass, Irvine Garland Penn, a journalist and educator; and Ferdinand L. Barnett, a prominent civil rights attorney, public official and journalist of Chicago, Illinois. More than twenty-thousand copies were disseminated at the fair.

The passion and dedication to Black community advancement shared by Wells and Barnett grew and the two married in 1895. A widower with two sons, Ferdinand and Albert, Ferdinand was supportive of Ida and their relationship seemed to thrive on their individual and collective interests. This was unusual, as many women held traditional roles of domestic life. Ferdinand and Ida were graced with four children of their own: Charles, Herman, Ida, Jr. and Alfreda. Ida would work hard, including limiting her travels, to balance her family life with activism. Also atypical, she retained her maiden name and added it, using a hyphen to her marriage surname; Ida’s retention of “Wells” was to honor her own identity.

Known as Ida B. Wells-Barnett, she worked as the editor of Ferdinand’s newspaper, the Chicago Conservator; it was created in 1878, making it the oldest Black newspaper in Chicago. Although Wells took her anti-lynching campaign to the White House, leading a protest in Washington, D.C. in 1898, she primarily remained more localized, becoming highly active in Chicago. She endeavored in ending segregation in the public-school system of Chicago; integrating women’s clubs; and opening the first kindergarten for Black children in Chicago. She co-founded the National Association for Colored Women in 1896, which focused on women’s suffrage and civil rights; its members included Harriet Tubman and Mary Church Terrell. In 1898, she acted, for four years, as secretary of the National Afro-American Council. In 1909, Wells-Barnett would be one of the participants of the inaugural meeting of the Niagara Movement and a co-founder of the movement’s manifestation, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). For several reasons, such as differing approaches in gaining equality for African-Americans, Wells-Barnett soon left the NAACP.

In 1910, Wells-Barnett founded and acted as the first president of the Negro Fellowship League, which assisted Black migrants from the South who had recently arrived in Chicago. Three years later, she started the Alpha Suffrage Club, which is possibly the first Black woman suffrage group in America. The purpose of the club was to organize women in Chicago to elect candidates who would best serve the interests of the Black community. In a now-famous incident, Wells-Barnett, as president, was invited to march in the 1913 Suffrage Parade in Washington, D.C. The organizers, wanting to please White, Southern suffragists, informed the “women of color” participants that they were to march in the rear of the parade. Refusing, Wells-Barnett stood along the sides of the march; when the cohort of White women suffragists of Chicago walked by, she joined her area, immediately integrating the march. The work of Wells and the Alpha Suffrage Club were highly integral in the 1913 passage of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Act.

(No copyright infringement intended).

The work of Wells-Barnett continued to expand, from working as a probation officer within the municipal court system in Chicago to being one of the first Black women in the country to run for a seat in the Senate. Although she lost the election, she used the experience to bring attention to causes in which she strongly believed. She called on presidents, including William McKinley and Woodrow Wilson, to create, institute and enforce reforms for equality and to end racial discrimination in places supported by federal funding.

On March 25, 1931, in Chicago, Ida B. Wells-Barnett passed from kidney disease; she was sixty-eight years old.

Because she wanted to tell her own truth about her life, in 1928, she started writing her own biography, Crusade for Justice but never completed it. Edited by her daughter, Alfreda, it was published in 1970 as Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells.

(No copyright infringement is intended).

Her legacy includes countless awards being created in her honor by organizations such as National Association of Black Journalists, the Investigative Fund and the Coordinating Council for Women in History. A memorial foundation and museum in her home city of Holly Springs, Mississippi, has been created to preserve and promote her passions and work. A public housing project in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side in Chicago was built in 1941 by the Public Works Administration; the buildings were razed in 2011.

(No copyright infringement is intended).

Wells-Barnett, posthumously, has been inducted in various halls of fame, including the National Women’s Hall of Fame, and was named, in 2002, by Dr. Molefi Kete Asante as a member of his list of 100 Greatest African Americans. In 2006, a commissioned portrait of Ida Wells-Barnett was installed in the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. In 1990, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp in her honor and in 2015, a Doodle was created by Google to commemorate her life and accomplishments. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which opened in 2018, contains a reflection space in memory of Well-Barnett. Also, in 2018, The New York Times published, in celebration of International Women’s Day, an “obituary” on her and Congress Parkway of Chicago was officially renamed “Ida B. Wells Drive” by its city council. It is the first street in downtown Chicago to be named in honor of a woman of color.

In 2019, a school as well as part of The Extra Mile National Monument, in Washington, D.C.; a marker in the courthouse square of Holly Springs; and a plaque in Birmingham, England, were named in tribute to her, her commitment and the positive changes she instituted.

“Having lost my paper, had a price put on my life, and been made an exile from home for hinting at the truth, I felt I owed it to myself and my race to tell the whole truth …”

~ Ida B. Wells Barnett