Located at 551 S. Tryon Street, the Harvey B. Gantt for African-American Arts+Culture is a 46,500 square foot structure that is a repository of Black culture, significantly of Charlotte, North Carolina. Opening in October 2009, it is contemporary in design and enveloped in glass windows, metals and brick. The inspiration for the design of this $18.6 million, four-story center was the Myers Street School.

This school was formerly located in the Brooklyn neighborhood area, a community populated by African-Americans that was eradicated in the 1960s due to the urban renewal of Charlotte. From 1886 to 1907, Myers Street School was the only public school that African-Americans could attend.

Issues of racial segregation and discrimination, especially in public accommodations, plagued the nation until the 1960s. It was during this period that student protest movements exploded on university campuses throughout America. North Carolina was not exempt, as protests, such as sit-ins, occurred throughout the state, including in Charlotte. At the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, a demand for the inclusion of African-American culture to be incorporated into the academic environment was met, leading, ultimately, to the creation of the Afro-American Cultural and Service Center.

The Afro-American Cultural and Service Center was preceded by UNCC’s initial creation of the university’s Black Studies Center. The Black Studies Center, developed to meet the demands and needs of the students, was directed by Dr. Bertha Maxwell Roddey. An associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Maxwell was a strong advocate of active student involvement within the community. Mary Harper, an assistant professor of English, added another critical facet of preservation of Charlotte’s African-American legacy to the Black Studies Center. Maxwell and Harper began to work together and, in 1974 and 1975, successfully held a Black cultural festival in Marshall Park, the former site of the Brooklyn neighborhood.

The Black Studies program at UNCC would become the foundation for the creation and outreach of the National Council on Black Studies, a student-led, not-for-profit organization that is centered upon the advancement of African and African-American Studies. The Afro-American Cultural and Service Center, co-founded by Maxwell Roddey and Harper, was designed to preserve and promote Black culture of the United States and specifically, Charlotte. This center was actively supported by the university president, Bonnie E. Cone. The collaboration between the Center and the University of North Carolina, Charlotte would be a strong relationship that presently continues.

For the next three decades, the Afro-American Cultural and Service Center was located in several sites. These sites include First Baptist Church, the McColl Center for Visual Art (currently known as the McColl Center for Art + Innovation) and Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church, which was on Myers Street. The site of Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church, which was honored as a historical site in 1982, was renovated with private donations and public grants. In March 1986, the Afro-American Cultural Center, as it was now known, opened; it was an 11,000 square foot, two-story structure located at Myers Street and 7th Street. This new three-leveled center contained an amphitheater and theater and housed classes for the arts, including dance, music, theatre and visual arts.

In late 2005, the proposed development for Wachovia Cultural Campus on Tryon Street was announced and included on this campus was to be a newly-constructed, $18 million Afro-American Cultural Center. In 2007, it was announced that the new Black culture center would be named the “Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts+Culture”; house the John and Vivian Hewitt Collection of African-American Art; and be designed by the Freelon Group Architects, which later led the design of the Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

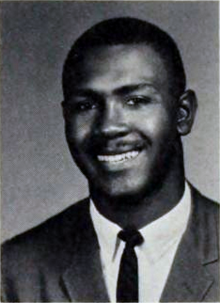

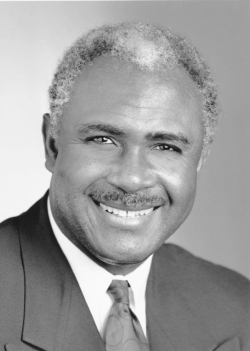

The decision to name it after Harvey B. Gantt was natural and fitting. Gantt, the first African-American to enter Clemson University in Clemson, South Carolina, was the first African-American mayor of Charlotte.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Upon graduating with honors from Clemson, thus, earning a Bachelor of Architecture, he earned a Master in Urban Planning from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After marrying Lucinda Brawley, the second African-American to attend Clemson University, he began his own successful architectural practice, Gantt Huberman Architects, which he still manages. A Democrat, Harvey B. Gantt also remains active in politics, having served in various capacities on diverse commissions, including as chair of the National Capital Planning Commission.

Change also came for the former site of the Black culture center and its previous host, the Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church. Although the Afro-American Cultural Center had been housed at “Old Little Rock” for thirty years, the church, in wanting to preserve its historic legacy, decided it wanted to buy back the building. The center’s past location on Myers and 7th Streets was re-purchased by Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church in 20o9 and re-dedicated as the Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Community Development Center.

Essential to the vision of the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts+Culture was the gift of the John and Vivian Hewitt African-American Art Collection. Acquired by NationsBank (currently known as Bank of America) in 1998, it was to be housed in the Afro-American Cultural Center; however, that site lacked the resources, such as space, to host the expansive collection. The collection contains fifty-eight original pieces from critically acclaimed African-American artists including Romare Bearden, John Biggers, Margaret Burroughs, Elizabeth Catlett, Jonathan Green, J. Eugene Grigsby, Jacob Lawrence, Henry Ossawa Tanner and Hale Woodruff. Grigsby, who was a cousin of Mrs. Hewitt, is an internationally celebrated artist and art educator. His greater involvement within the world of African-American art allowed him to connect the Hewitt couple with a number of Black artists who autographed their work to the burgeoning collectors. The inscriptions of the artists render these pieces even more valuable, from a cultural and financial perspective.

The collection originally belonged to John and Vivian Hewitt. He was a professor of English at the historical Black institution, Morehouse College, in Atlanta, Georgia. His wife, Vivian, was the first African-American librarian to work at Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. They met when she later worked as a librarian and taught at Atlanta University, presently known as Clark Atlanta University, and married in 1949. In the article, “African-American Art Collector Vivian Hewitt Recalls How Works Were Found”, written by Virginia Linn for Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Hewitt shared the story behind their curation of their collection. While on honeymoon in New York City, they purchased a print in a museum with the intent to decorate their suite. Over the years, they began to travel and bought art from their time on holiday in places such as islands in the Caribbean and Mexico. They even exchanged original artistic works on gift-giving occasions.

In 1952, the Hewitt family moved to New York City. Through their relationship with John’s sister, Adele Glasgow, they met many artists who had become famous during the Harlem Renaissance. Adele, who operated the Market Place Gallery, acquired original pieces that were exclusive to her gallery and clients, which included John and Vivian. In the Linn article, Vivian proudly affirmed, “We started investing in our own heritage and culture … Their work was affordable then.” However, when The New York Times, in the 1970s, emphasized the growing value of African-American art, it started being actively bought by White collectors. Hewitt added, “In essence, it said that African-American art was here to stay, and [collectors] better get on the bandwagon … It was a turning point for people recognizing the importance of African-American artists. Because of racism and the tenor of the times, this is what happened to exist.”

In 2000, John Hewitt passed away before seeing the collection become a critical component to the permanent collection of the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts+Culture. The collection toured across the United States for ten years prior to being exhibited at the Gantt Center in 2007 and in many of the cities, Vivian was featured as a guest speaker.

(No copyright infringement intended).

The tour of the John and Vivian Hewitt African-American Art Collection and the opening of the newly-designed building by the Freelon Group Architects has further strengthened the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts+Culture in becoming a world-class institution.

Entry to the center may be accessed through the lobby located on the second floor. Although there are stairs, the center is ability-accessible, which includes ramps and escalators that are available to the public. A glass atrium is encased within the stairs and escalators, both of which extend from the outside to the inside of the center. The inspiration for their design is “Jacob’s Ladder” from Genesis, the first book in the Bible.

The plaza connects the Harvey B. Gannt Center for African-American Arts+Culture with other buildings in the Levine Center of the Arts. Visitors to the plaza are entreated to view Juan Logan’s Intersections, which incorporates the Kuba diamond and chevron patterns from the Democratic Republic of Congo. These shapes and their placements illustrate the connections and similarities of diverse cultures. The same year that this African-American cultural center opened, the American Institute of Architects gifted the Freelon Group the 2009 Thomas Jefferson Award for Public Architecture. Their stellar design of the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts+Culture was a contributing factor in the architecture organization being awarded.

In the east wing, installed is a David Wilson quilted art piece, Divergent Threads, Lucent Memories, which pays homage to the historic Brooklyn community. Building upon the theme of quilts and their significance in the African-American community, there is a rain screen, complete with alternating windows, perforated metal panels and fluorescent lights that are reminiscent of the stitching that holds the piece together.

Past exhibits of their extensive and grand collection that have been on show include Charlotte Collects Elizabeth Catlett: A Centennial Celebration (2015); Dance Theatre of Harlem: 40 Years of Firsts; Jordan Casteel: Harlem Notes (2017); By and About Women: The Collection of Dr. Dianne Whitfield Locke and Dr. Carnell Locke (2018); and Question Bridge: Black Males (2019).

The Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts+Culture is highly active within the global community and their outreach involves educational programming, cultural development and social activities such as Walk Up Wednesdays, Fine Art Friday and Family First. Aside from K-12 educational programming, there is adult programming as well as guided tours that are optional.

In 2016, Google Cultural Institute featured the Harvey B. Gantt in its Black History Month online gallery that celebrated Black culture. It was one of fifty institutions highlighted and celebrated.

In August 2019, the center coordinated an excursion to South Africa. With an option to also visit Ghana on this escorted tour, items on the agenda, as per the center’s website, were:

- Three-day luxury photo safari at the stunning Kapama River Lodge

- Explore Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela served 18 years

- Guided tour of Zeitz Museum, the world’s largest museum of contemporary African art

- Wine tasting at black-owned Seven Sisters Vineyards in the scenic Cape Winelands

- Ghana’s Cape Coast Castle, the point of departure for many enslaved Africans

- Visit Ntonso Adinkra village and create your own fabric design

- Experience the rich history and culture of the Ashanti in Kumasi, Charlotte’s sister city

Because this center includes being ability-accessible to the public, available onsite are wheelchairs for usage. Additionally, prior arrangements may be made to greater accommodate an individual with specific needs and the Center is involved with the No Dark Doors, a program which assists those who are visually challenged.

The Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts+Culture is open from 10am to 5 pm, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday; they are open on Wednesday, from 10am to 9pm; and on Sunday, from 11am to 5pm. Areas, such as the Harper-Roddey Grand Lobby, the Learning Center, the Mezzanine, the Performance Suite, the Rooftop Pavilion and the Conference Room, or the entire beautiful facility may be rented for special occasions, such as weddings and social receptions, as well as for professional meetings and corporate training.