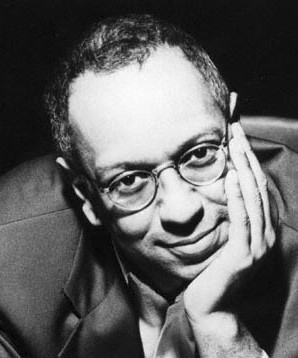

“Wolfe’s influence has established him as ‘one of the leaders of a new generation … in the American theater – one whose work raises provocative questions about racial culture, history, and identity …’”

~ Hilary De Vries, contributor, Los Angeles Times

On September 23, 1954, a baby boy was born to Costello and Anna (née Lindsey) Wolfe in Frankfort Kentucky. The third of what would be the couple’s four children, the parents named him George Costello. Costello worked as a clerk with the Kentucky Department of Corrections and Anna was a librarian and principal at a Rosenwald Laboratory School.

This school was part of the Rosenwald Project, which constructed more than five thousand schools, shops and homes of teachers in the American South during the early 20th century. Sourced from a collaboration between Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington, these schools were developed to counter the numerous deficiencies suffered by African-American children and families due to segregation. Julius Rosenwald was an immensely wealthy, Jewish-American entrepreneur and philanthropist who is perhaps best known for his roles as co-owner and president of Sears, Roebuck and Company. Booker T. Washington was the African-American founder and president of Tuskegee University, a historically Black institution of higher learning. Also an advisor to several U.S. presidents, Washington was a strong proponent of vocational education.

A move of the Wolfe family led George to attend integrated schools. In speaking with The New York Times, Wolfe shared “I was 13 or 14 before I was thrust into the White world. And ever since then, it’s become clearer and clearer to me that I was part of a generation of Black children who were raised like integration soldiers, who were groomed to invade White America. I don’t know how conscious it was, but with my parents it was definitely: ‘They think you’re less than; you’ve got to be better than.’”

When he attended Frankfort High School, his extracurricular activities included the school’s literary magazine and the drama club. His passion for theatre grew after seeing a production of Hello Dolly in New York City when he was a young teenager. He attended summer workshops at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio and it was there that he began directing productions.

After graduating Frankfort High School, he, in 1972, enrolled in college to further his interests. Wolfe’s first matriculated his parents alma mater, Kentucky State University, a historically Black institution of higher learning. After his freshman year, he left for the West Coast, where he attended Pomona College in Claremont, California. There, he continued developing his love for and skills in theatre arts. George C. Wolfe’s intent and efforts were rewarded when Up For Grabs, which he directed, won the Pacific Southern Regional’s award at the American College Theater Festival.

1976 was a great year for George C. Wolfe, as he earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in Theater in 1976 and also met C. Bernard Jackson, the founder and executive director of the Inner City Cultural Center. Located in Los Angeles, the Center was one of the first institutions in the United States to promote diversity in cultural arts. When Wolfe shared with Jackson a draft of a scene he was crafting, Jackson immediately encouraged Wolfe and gave him money to continue his development of the work. This funding made possible Wolfe’s first production, Tribal Rites, or The Coming of the Great God-bird Nabuku to the Age of Horace Lee Lizer, which premiered at the Inner City Cultural Center. Wolfe affirmed in “Recalling C. Bernard Jackson’s Gift” published in the Los Angeles Times that Jackson’s belief in him and support of his Tribal Rites production were essential to his artistic evolution.

After remaining in California for several years, George C. Wolfe relocated to the East Coast, settling in New York. Returning to his academic studies, he entered New York University. Wolfe graduated in 1983, having earned his Master of Fine Arts degree in dramatic writing and musicals.

George C. Wolfe immediately set to work and his plays, Paradise (1985), The Colored Museum (1986) and Spunk (1990) were his introduction to many interested in theater and/or Black culture. Opening Off-Broadway, these productions presented themes often negated or omitted from mainstream theater productions.

His work was even more recognized and celebrated when The Colored Museum won the Dramatists Guild’s Elizabeth Hull-Kate Warriner Award in 1986. Receiving mixed reviews was expected by Wolfe. In speaking with the Los Angeles Times, the director confided about The Colored Museum, “When [the play] opened, the self-appointed Black crowd said, ‘This is horrifying. This is horrifying. I can’t believe he is actually saying that’.…And that was painful. Because that was exactly the place where I was coming from … All the Whites went into programmed guilt and the Black people went into programmed rage and the play kept saying, ‘You can’t do that.’ It was really a play about self-empowerment. About how I am now going to define myself the way that I am capable of.”

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1990, George C. Wolfe won an Obie Award for “Best Off-Broadway Director” for Spunk, which was an adaptation of three short stories written by Harlem Renaissance legend, Zora Neale Hurston. Also that year, Wolfe served as the resident director and producer of the New York Festival.

1991 was both trying and triumphant for him. He had suffered kidney failure but fortunately, his older brother, William, donated one of his kidneys to George.

Recovering, Wolfe became even more renown when his production and direction of Jelly’s Last Jam became critically-acclaimed. This musical was centered upon the life and career of Ferdinand LaMothe, better known as “Jelly Roll Morton”. Highlighted in this musical are issues of race, class, cultural heritage and social access, all couched in this new genre, “jazz”, which Morton proclaims he created.

First opening in Los Angeles in 1991, Jelly’s Last Jam premiered on Broadway in 1992. The production in Los Angeles featured Obba Babatunde as Jelly Roll but in New York, Gregory Hines performed in the lead role. Also in the Broadway production were Ken Ard, Mary Bond Davis, Keith David, Ana Duquesnay, Savion Glover, Tonya Pinkins and Ruben Santiago-Hudson. Brian Stokes Mitchell and Phylicia Rashad acted in later productions on Broadway.

Receiving 11 Tony nominations in 1992, Gregory Hines won “Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Musical”, Tonya Pinkins won “Best Performance by a Featured Actress in a Musical” and Jules Fisher for “Best Lighting Design”.

Jelly’s Last Jam also won five Drama Desk Awards in 1992. George C. Wolfe won for “Outstanding Book of a Musical”; Gregory Hines won “Outstanding Actor in a Musical”; Tonya Pinkins won “Outstanding Featured Actress in a Musical”; Luther Henderson for “Outstanding Orchestrations”; Susan Birkenhead for “Outstanding Lyrics”; and Jules Fisher for “Outstanding Lighting Design”.

The musical also won three Outer Circle Critics Awards in 1993. Jelly’s Last Jam won “Best Broadway Musical”; Tonya Pinkins won “Best Actress – Musical”; and Hope Clark, Gregory Hines and Ted Levy won “Best Choreography”.

Also in 1993, George C. Wolfe won a Tony Award for “Best Direction of a Play” for Tony Kushner’s Angels in America: Millennium Approaches. Kushner won the Pulitzer Prize Award for “Drama” in 1993 for his play, Angels in America. The following year, Wolfe directed Perestroika, the second part of the Angels in America series. His work was nominated for another Tony Award.

George C. Wolfe became the artistic director and producer of the New York Shakespeare Festival/Public Theater. He served in this capacity from 1993 until 2004. During this time, he continued to compose, direct and produce both on stage and film. His works include Broadway hits, the musical Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk (1996), in which he worked with Savion Glover again in this examination of Black history viewed through the lens of tap dance and Suzan Lori Parks’ Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Topdog/ Underdog (2002).

Having directed Santiago-Hudson’s theater production of his autobiographical Lackawanna Blues, Wolfe reprised this role in his debut film direction of it for HBO in 2004. It starred Santiago-Hudson, S. Epatha Merkerson, Carmen Ejogo, Macy Gray, Hill Harper, Terrence Howard, Mos Def, Rosie Perez, Liev Schreiber, Jimmy Smits and Jeffrey Wright. This film won many awards, including George C. Wolfe receiving the 2006 Directors Guild Award for Best Directorial Achievement. For her role in the Wolfe-directed Lackawanna Blues, S. Epatha Merkerson won numerous accolades including a Black Reel for “Best Actress in a Made for TV Movie or Miniseries”; an Emmy Award for “Outstanding Lead Actress in a Miniseries or a Movie”; a Golden Globe Award for “Best Performance by an Actress in a Mini-Series or a Motion Picture Made for Television”; a PRISM Award for “Performance in a TV-Movie or Miniseries”; and a Screen Actors Guild Award for “Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Television Movie or Miniseries ” in 2006.

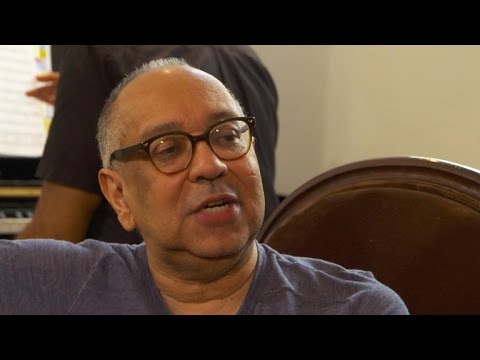

Wolfe continued directing film and his works include The Devil Wears Prada (2006), Nights in Rodanthe (2008) and The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2017). Simultaneously, he returned to Broadway. His directed productions such as Caroline or Change (2004), A Free Man of Color (2010), The Normal Heart (2011), Lucky Guy (2013), Shuffle Along, or, the Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921 and All That Followed (2016) and The Iceman Cometh (2018). Wolfe was nominated for numerous awards, including Tony and Drama Desk, for these theater works.

Shuffle Along was a reprisal of the Black musical which first opened on Broadway in 1921. Written by Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles, it featured lyrics and music by Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle. Wolfe’s adaptation dealt with the same issues of Miller and Lyles, including putting on a Black production for Broadway in the early 1920s as well as its impact on American theater and race relations. Wolfe and Glover reunited, with Glover as the choreographer. Stokes Mitchell was again featured in a Wolfe production. Shuffle Along starred Audra McDonald, Brandon Victor Dixon, Joshua Henry and Billy Porter. Though it did not win any, it was nominated for ten Tony Awards in 2016.

(No copyright infringement intended).

The Iceman Cometh, written by Eugene O’Neill, was revived and starred Denzel Washington as the lead, Theodore “Hickey” Hickman. It also starred Tammy Blanchard, Bill Irwin, Colm Meaney, David Morse and Frank Wood. This 2018 production of The Iceman Cometh reunited Wolfe with award-winning lighting designer Jules Fisher.

George C. Wolfe has also been honored for his incredible work by his 2013 induction into the American Theater Hall of Fame. Conscientious, Wolfe resigned from his membership in the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities in 2017. He and all the committee’s members served their resignation in protest of comments made by Donald Trump after a Neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Virginia that led to the murder of Heather Heyer, a White, nonviolent protester, by James Fields, Jr., a White domestic terrorist.

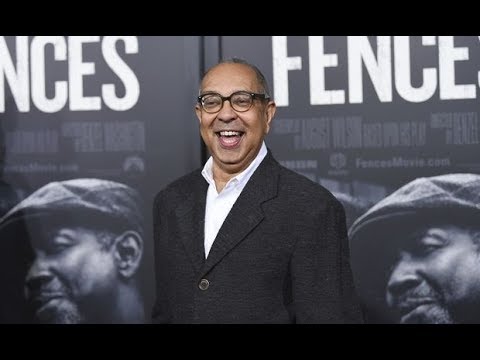

After directing theater productions of Gary: A Sequel to Titus Andronicus in 2019 and Overcoming in 2020, George C. Wolfe directed the film adaptation of August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Premiering on Netflix in 2020, it starred Viola Davis, Chadwick Boseman, Glynn Turman, Colman Domingo and Michael Potts. Wolfe worked again with Ruben Santiago-Hudson, who adapted Wilson’s screenplay, and Denzel Washington, who co-produced the film. Set in 1927, the film is centered upon the ups and downs of Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, the “Mother of the Blues”, and her bandmates during a recording session. This was Chadwick Boseman’s final appearance on film.

George C. Wolfe has recently accepted the role of chief creative officer for the Center for Civil & Human Rights in Atlanta, Georgia. The recipient of many honors, George C. Wolfe has been named a “Living Landmark” by the New York Landmarks Conservancy and honored with grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Institute of Musical Theatre and the Rockefeller Foundation. Awards he has received include Audelco Awards, a Paul Robeson Award, the “Distinguished Alumni Award” from New York University, HBO/USA Playwrights Award, the LAMBA Liberty Award and the Caring Spirit Award by the Asian and Pacific Islander Coalition on HIV/AIDS (APICHA).

“I’m a warrior. I know the right conditions under which good work happens. And there are a number of artists who may not be as good at being warriors as I am, but they’re good artists. If I can use my connections and the force of my personality to create structures for other artists, great, because other people did that for me.”

~ George C. Wolfe

For greater enlightenment...

-

A Homecoming: George C. Wolfe | Kentucky Life | KET.org

-

Icons & Innovators: George C Wolfe

-

"Shuffle Along": George C. Wolfe on a "footnote" of 1921

-

The Colored Museum (1991)

-

Noise/Funk - Charlie Rose interview

-

"Bring in ‘da Noise" With Savion Glover (2002) - MDA Telethon

-

George C. Wolfe On His Film Ma Rainey's Black Bottom