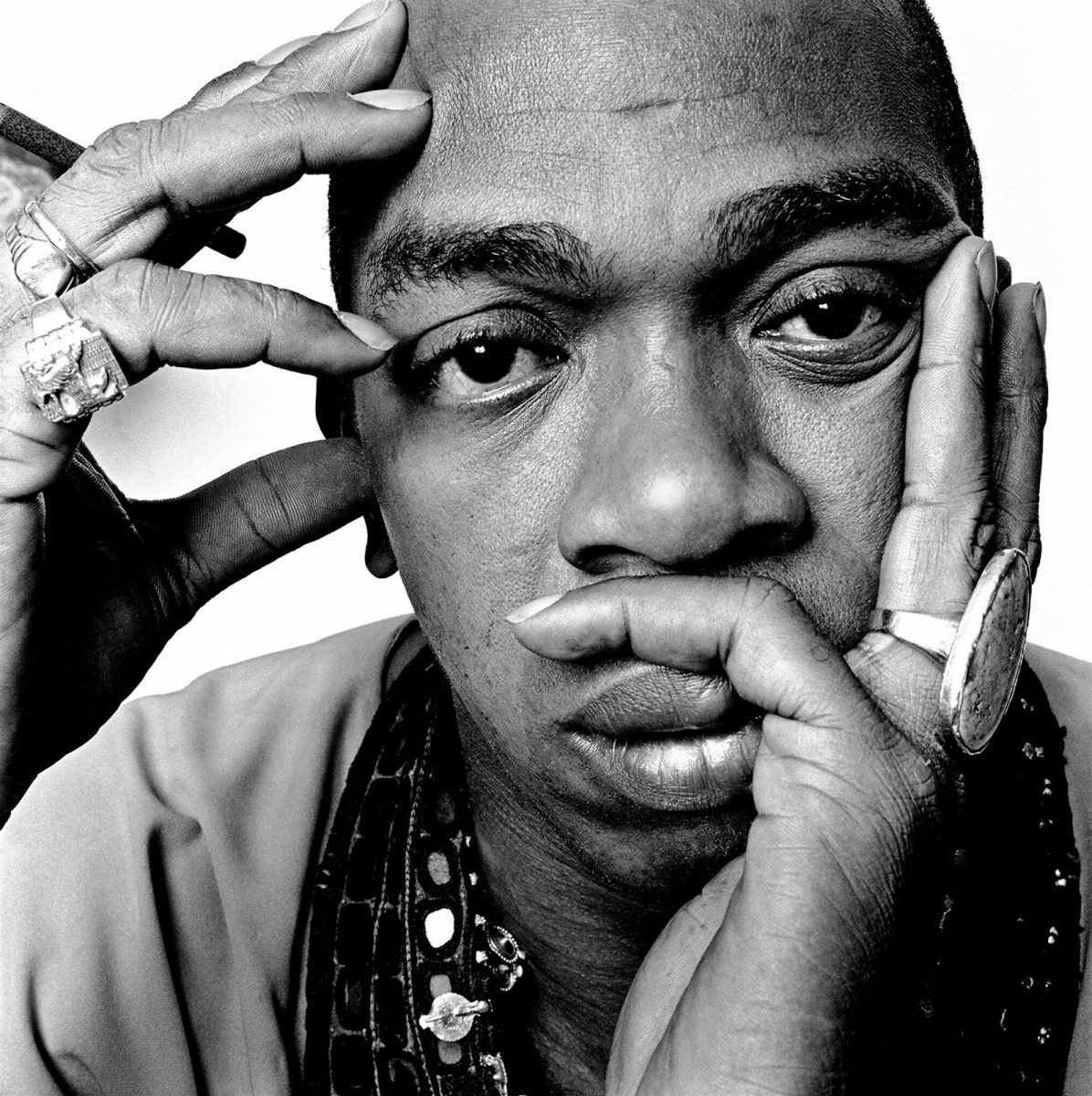

“There is hardly a branch of the arts in which dancer, choreographer, graphic artist, costume designer, actor, stage director, photographer, musician, and writer Geoffrey Holder has not made his mark.”

~ Lucy E. Cross, Music historian

On August 1, 1930, a baby boy, Geoffrey Lamont, was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago. His parents, Arthur and Louise (née de Frense) Holder, immigrated to the country’s capital city from Barbados. He was the couple’s youngest of their five children, who included Jean, Marjorie, Arthur and Kenneth. Born into their middle-class family, Geoffrey was educated at Tranquility School and Queen’s Royal College, a premier secondary school.

As a small boy, Geoffrey was mentored by his older brother, Arthur, who was affectionately known as “Boscoe”, his nickname from childhood. Boscoe taught him many skills such as painting and dancing. At sixteen years old, Boscoe founded his own dance troupe, The Holder Dancing Company, and even encouraged Geoffrey to join it. Geoffrey made his debut for his brother’s dance company when he was only seven years old.

The influence that Boscoe, who was nine years older, had on his younger brother would forever impact Geoffrey. Boscoe became successful as a choreographer, dancer, designer, musician and painter; Geoffrey would also follow to be successful in those professions. Boscoe and, later, Geoffrey gained roles for radio and television. The brothers both left Trinidad for greater opportunities to advance. In the late 1940s, Boscoe moved to London, England. By the 1950s and 1960s, he had popularized his native culture’s steel-pan band playing and limbo dancing in Britain and is credited with bringing these art forms to the European country.

With Boscoe living in London, Geoffrey became the director and lead dancer for The Holder Dancing Company. In these roles, he guided the troupe in touring internationally, including Puerto Rico, the West Indies, and the United States. In 1952, Agnes de Mille, an acclaimed choreographer, attended a performance of the Holder Dance Company is St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. Impressed, she invited Holder to New York City to audition for Sol Hurok. Hurok was an esteemed impresario who managed African-American greats, including opera singer Marian Anderson and dancer/choreographer Katherine Dunham, as well as dance companies such as the Original Ballet Russe, whose principal venue was Monte Carlo.

In order to finance the company’s trip to New York City, Holder sold twenty of his paintings. Having vended his first two paintings at the age of fifteen, he had established himself as an artist by 1954, when the troupe auditioned for Hurok. Hurok declined to sponsor The Holder Company; while some of the troupe returned to Trinidad, others, including Holder, remained in the States.

Geoffrey Holder, having saved for two years, planned to succeed in New York City. He was armed with the sage wisdom from his father, as per music journalist Lucy E. Cross in her biography on Holder for Masterworks Broadway. Prior to his leaving Port of Spain, he advised his son, “Don’t go to New York looking for atmosphere; you must take it with you.”

For the next two years, Geoffrey taught folkloric styles of dance at the Katherine Dunham School of Cultural Arts. During this period, Dunham, who founded and directed the only permanent, self-subsidized African American dance troupe at that time, was in Europe. This was a time of good fortune for Holder, as all-Black productions; Black music, including calypso; and Black dance forms, including modern and folk, were becoming popular. Much of the respect and admiration that these cultural forms of the Africa Diaspora garnered were made possible by the passion, research and dedication of Dunham and Pearl Primus, the pioneering dancer, choreographer and anthropologist who hailed from Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, Holder’s home country.

In 1954, Geoffrey Holder’s commitment manifested in his debut as a featured dancer on Broadway. At a dance recital, he connected with Arnold Saint-Subber, who was producing a show that contained Caribbean themes. The biography on Holder profiled by the National Visionary Leadership Project describes this role as being “a pivotal point, both personally and professionally, because the towering (6’6”), breathtakingly limber interpretive dancer was chosen to perform in Harold Arlen’s Broadway musical, House of Flowers.” The musical, described by Jennifer Dunning and William McDonald in “Geoffrey Holder, Dancer, Actor, Painter and More, Dies at 84” of The New York Times, was “a haunting, perfumed evocation of West Indian bordello life, with music by Harold Arlen and a book by Truman Capote, based on his novella of the same name. Directed by Peter Brook at the Alvin Theater, it starred Diahann Carroll and Pearl Bailey and among its dancers was a ravishingly pretty young woman named Carmen de Lavallade.”

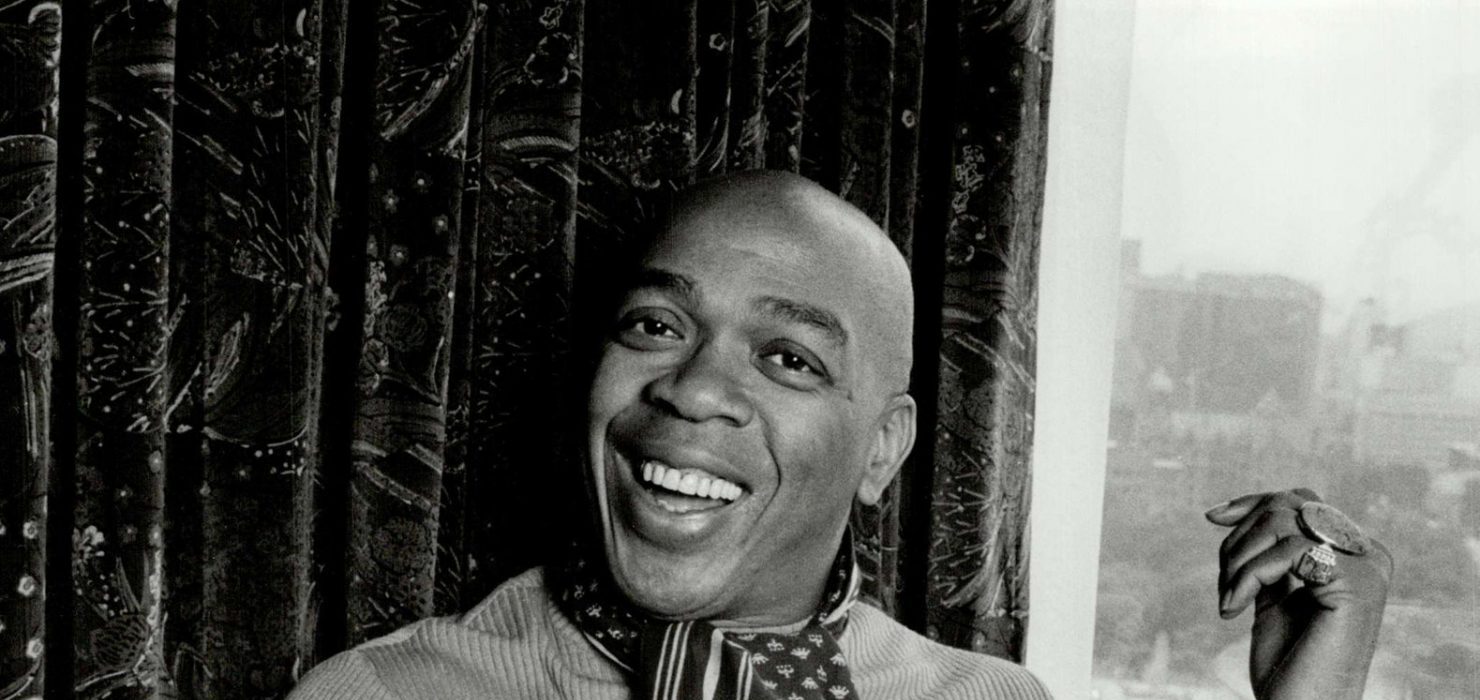

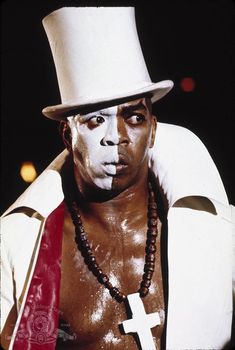

It was sourced from Pinterest (No copyright infringement intended).

Professionally-speaking, in House of Flowers, Holder acted in two roles. He portrayed Lord Jamison and Baron Samedi, loa, or guardian of the cemetery and the spirit of death, sex and resurrection in Haitian voodoo culture. While this was the first musical of Capote it was also the first theatrical production outside of Trinidad and Tobago to feature the steel pan, an instrument of the Caribbean. The steel pan, utilized by a trio, was incorporated due to Holder’s input; he recruited pannists Michael Alexander, Roderick Clavery and Alphonso Marshall from his home country to perform. It would be the first time a steel band performed on Broadway. Additionally, Holder choreographed the “Banda Dance” section in the musical.

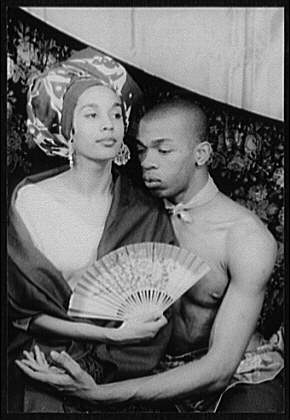

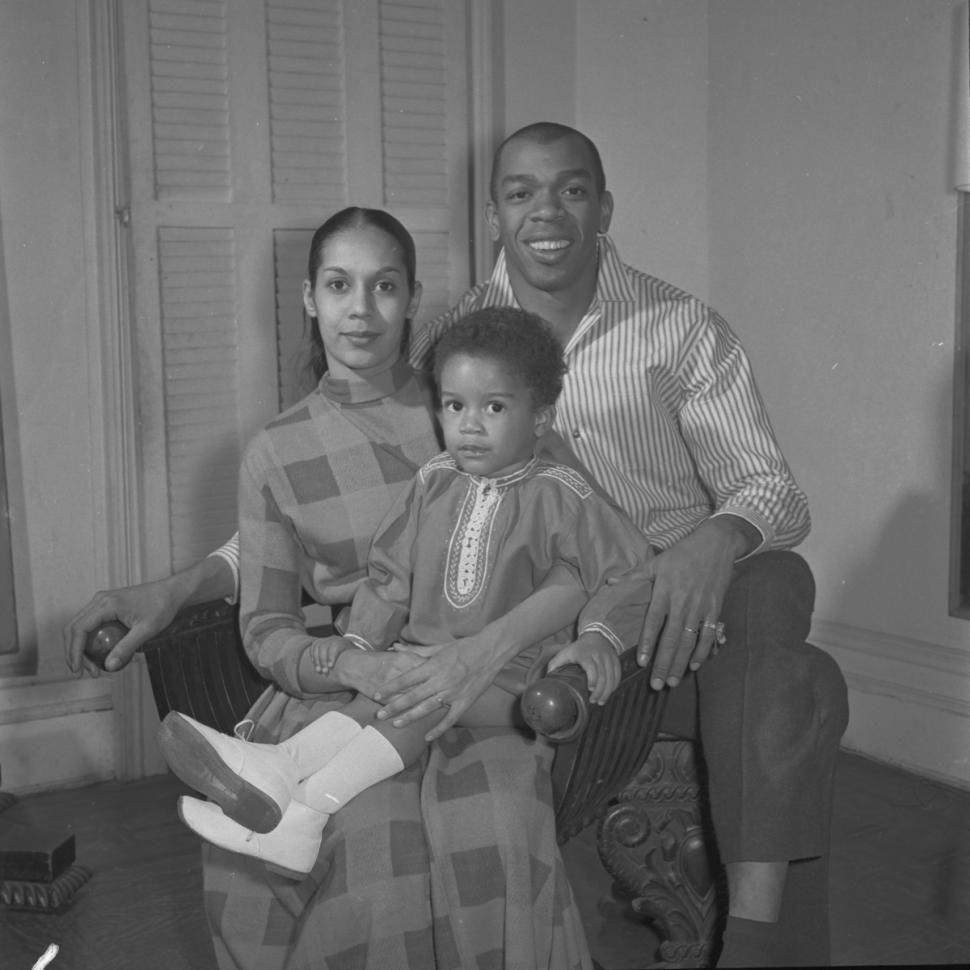

Personally, Holder also experienced joy in falling in love with Carmen de Lavallade. She and her dance partner, Alvin Ailey, performed alongside Holder in House of Flowers. In 1955, Holder and de Lavallade married and were later blessed with a son, Léo Anthony Lamont.

This image is sourced from Pinterest (No copyright infringement intended).

From 1956 to 1958, the Holders performed as principal dancers at the Metropolitan Opera Ballet. De Lavallade, whose parents were Creoles of New Orleans, Louisiana, was extremely close with her cousin, Janet Collins. Collins, who was also of Creole descent, was the first Black prima ballerina at the Metropolitan Opera Ballet. Also, in 1956, Holder founded his own dance troupe, Geoffrey Holder and Company; he directed it until 1960 when it disbanded.

After 165 performances, House of Flowers closed in 1956. He then choreographed and danced in Central Park in a revival of Rosalie by the Gershwin brothers, George and Ira. While performing, Holder still painted and was even awarded that year a Guggenheim Fellowship in fine arts for his work. His art, as the writers detailed in The New York Times article, “…drew on folk tales and often delivered biting social commentary. On canvases throughout the studio, sensuous nudes jostled for space with elegantly dressed women, ghostly swimmers nestled beside black Virgin Marys, bulky strippers seemed to burst out of their skins, and mysterious figures peered out of tropical forests.” His works were exhibited in prestigious venues worldwide, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York City and the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. Holder’s art was collected by everyday people and the well-known, including African-American entertainer, Lena Horne. He would paint, as well as photograph and sculpt, throughout his life.

In 1957, Geoffrey Holder starred as “Lucky” in an all-Black production of Waiting for Godot. This role would be his non-dance debut in theatre. As Dunning and McDonald wrote of his new part, Holder “landed a notable acting role playing the hapless servant Lucky in an all-Black Broadway revival of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, directed by Herbert Berghof. The show, just seven months after the play’s original Broadway production, closed after only six performances because of a union dispute, but the role, with its rambling, signature 700-word monologue, lifted Mr. Holder’s acting career.”

This image was sourced from Pinterest (No copyright infringement intended).

Geoffrey Holder soon transitioned to acting in films, first being seen in All Night Long, a 1962 British remake of William Shakespeare’s Othello. Over the next several decades, he continued to capture audience members’ attention with his portrayals in movies, including Doctor Dolittle, Annie, and Boomerang. However, it would be his role, as the top-hatted, cigar-smoking Baron Samedi, again, in Live and Let Die for which he will probably be best remembered. Released in 1973, Holder, reviving his role as the loa he portrayed in House of Flowers, was a villain in the James Bond classic. In Live and Let Die, Holder also recreated the Banda performance he originally choreographed for the musical. Holder would also act on television, including in Androcles and the Lion and The Gold Bug.

His unforgettable baritone voice and crisp diction, accented with his lush, Caribbean lilt, made Geoffrey Holder a natural for narration, voiceovers and commercial campaigns. His voice can be heard in several genres, such as the Cheshire Cat in the 1982 version of Alice in Wonderland and as Master Pi in Cyberchase; and as the narrator in Tim Burton’s production of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory film and video game. He became immensely popular during the 1970s and 1980s for being the spokesman for the soft drink, 7 Up. In the advertisements, he promised that 7 Up, the “un-cola” was “crisp and clean, with no caffeine; never had it, never will.” In 2011, Holder reprised his role for the clear pop when he appeared as himself for Marlee Matlin’s team in the season finale of The Celebrity Apprentice. To be able to perform in this capacity was especially triumphant for Holder, as he struggled with stammering as a youth until early adulthood.

Though he attained accolades in these diverse aspects of the arts, Geoffrey Holder continued to dance and choreograph. In 1964, he and his wife, with whom he often collaborated, performed again on Broadway in Josephine Baker’s revue. In 1972, Holder was awarded the Trinidad & Tobago Humming Bird Gold Medal for Dance.

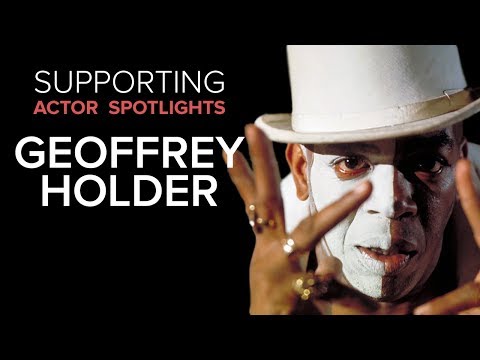

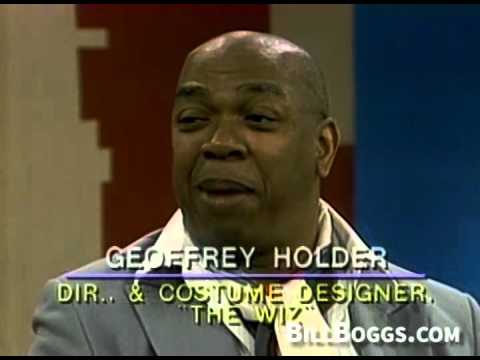

In 1975, Holder made history in being the first Black man to be nominated for a Tony Award in direction and one in costume design. The nominations were for his work in The Wiz, an all-Black musical production of The Wizard of Oz. Geoffrey Holder, continuing to be a man of “firsts”, won both Tony awards. That year, Holder also received the Drama Desk Award for “Outstanding Costume Design” for his contribution to the urban musical. With 1672 performances on Broadway, the 1975 production of The Wiz won seven Tony Awards, including for “Best Musical” and ran for more than four years.

Three years later, Geoffrey Holder directed and choreographed Timbuktu!, an all-Black musical version of the musical, Kismet by Robert Wright and George Forrest. Entrenched with African elements, including folklore, Holder, in 1978, would be recognized again for his work. Nominated for a Tony Award and a Drama Desk Award for costume design and for a Drama Desk Award for choreography, Holder also created the cover for the Playbill of Timbuktu! Premiering on Broadway, the musical had a 221-performance run and starred Eartha Kitt.

As a choreographer, Geoffrey Holder created classic dance performance pieces for friends and colleagues Alvin Ailey and Arthur Mitchell, and organizations such as The Boys’ Choir of Harlem and Friends. With Ailey, who created his own dance company, the Alvin Ailey Dance Theatre, Holder choreographed dances, composed music and designed costumes for productions, including The Prodigal Prince in 1971 and Dougla in 1974. The former production was inspired by the life and art of Hector Hyppolite, a Haitian folk painter; the latter was centered upon the circumstances surrounding a mixed-race Caribbean wedding, as “dougla” is a reference to persons of African and Indian heritage.

With Mitchell, who co-founded the Dance Theatre of Harlem, Holder also choreographed dances, composed music and designed costumes. Holder’s production of Banda in 1982, was revived by the Dance Theatre of Harlem in 1999. Also performed in 1982, John Taras produced for the dance theatre its own version of the Russian fairytale, The Firebird. In this version, the setting had been changed to a tropical forest in the Caribbean. Geoffrey Holder designed the sets as well as the costumes; one in particular, was comprised of more than thirty hues.

Holder was even involved in the book industry. In 1959, he co-authored with Tom Harshman a book on Caribbean folklore, Black Gods, Green Islands; it was illustrated by Holder. In 1973, he released his own book of recipes, Geoffrey Holder’s Caribbean Cookbook. In 1986, Holder’s book, Adam, that featured his photography, was published. In 2002, a coffee-table book, Geoffrey Holder: A Life in Theater, Dance and Art, by Jennifer Dunning was released; the book contained 250 illustrations. He was featured prominently in three documentaries, Geoffrey Holder: The Unknown Side by Andrzej Krakowski in 2002; Joséphine Baker: Black Diva in a White Man’s World by Annette von Wangenheim in 2006; and Carmen & Geoffrey by Linda Atkinson and Nick Doob in 2009.

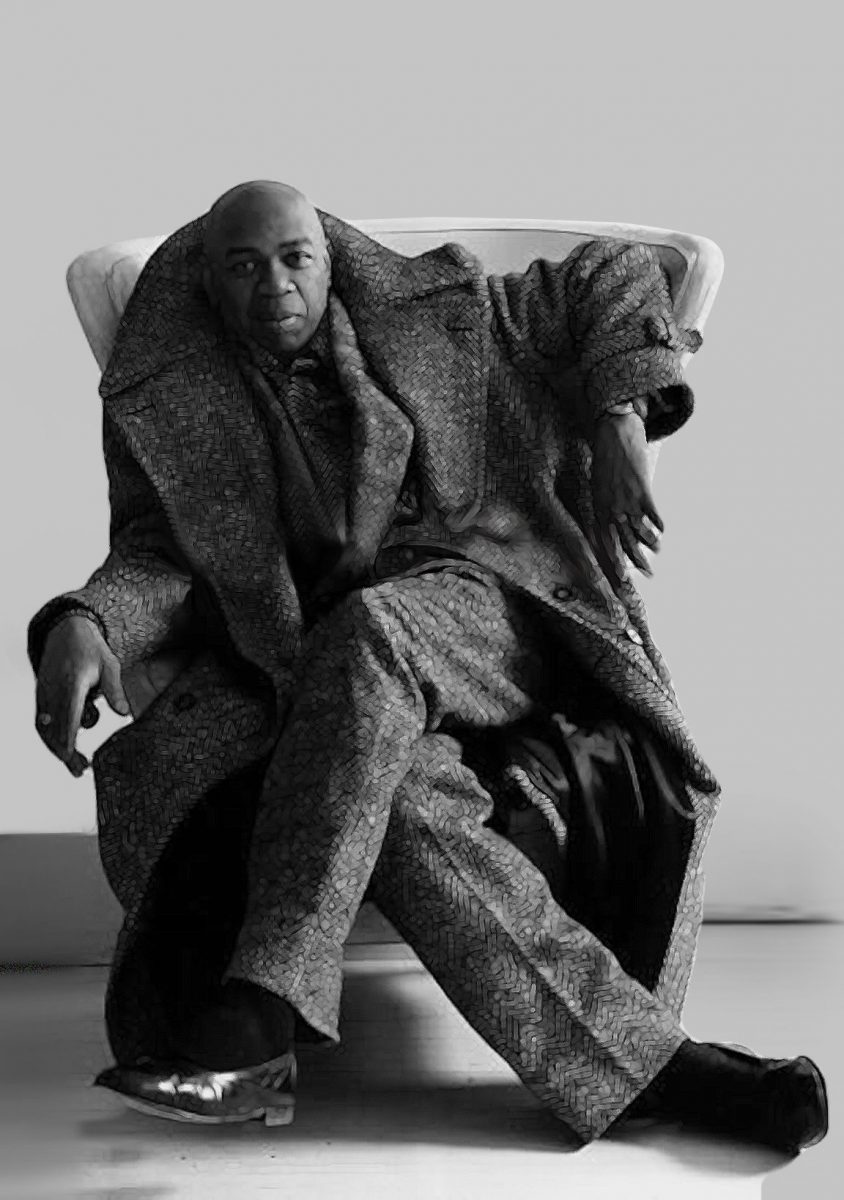

On October 5, 2014, Geoffrey Holder passed away from complications from pneumonia; he was eighty-four years old. Incredibly talented, he worked consistently and constantly to make the most of his many gifts. He has inspired many by his creations and contributions.

“I create for that innocent little boy in the balcony who has come to the theater for the first time … He wants to see magic, so I want to give him magic. He sees things that his father couldn’t see.”

~ Geoffrey Holder