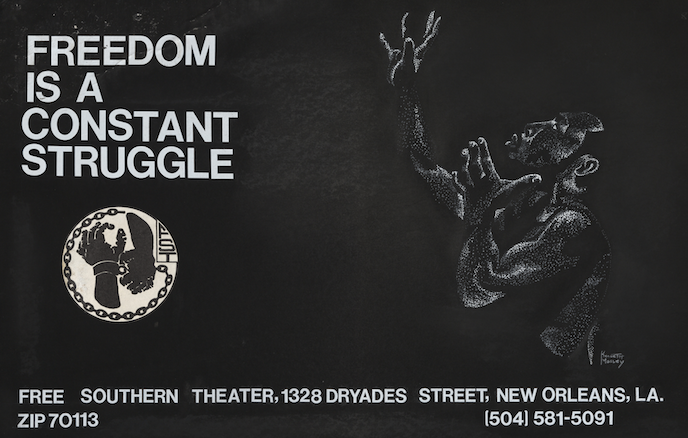

Founded by John O’Neal, Gilbert Moses, and Doris Derby at Tougaloo College in Madison County, Mississippi in 1963, the Free Southern Theater (FST) was a cultural, performing arts and educational extension of the Civil Rights and Black Arts Movements. Although it ceased operating in 1980 due to low financing as well as administrative and creative differences, the FST was highly significant in developing the Black Theater Movement in the United States.

The uniting of O’Neal, Moses and Derby was natural. On the information page of the Freedom Southern Theater of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, their commonalities are highlighted. At SNCC Digital Gateway, it states, “The trio was drawn together by their artistic and movement backgrounds. Derby, who studied African diasporic art and culture at Hunter College in New York City, was a SNCC field secretary in Southwest, Georgia before heading up an adult literacy project in Jackson, Mississippi. O’Neal was a recent graduate from Southern Illinois University where he performed in a number of plays. After graduation, he dropped his plans to move to New York in order to work with SNCC full-time in Mississippi. Moses was the most established actor of the group, having already performed in off-Broadway productions at the age of 21. He was working as a reporter for the Mississippi Free Press, a movement paper based in Jackson, where he met O’Neal and Derby.”

Building upon their active work in civil rights, they saw the utility of Theater as a vehicle of Black cultural expression and political enlightenment for those in the Deep South who had little to no exposure. Selection of this mode of communication was especially pivotal to Derby and O’Neal, who had served as field directors of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Jackson, Mississippi. Understanding the extreme level of poverty in which many, especially African-Americans, lived while desiring to reach as many people as possible, all aspects of Theater were presented to the public free of charge.

The Free Southern Theater aspired to use Theater to both emphasize the numerous, diverse aspects of Black culture and activate social change. In the information stub, “Free Southern Theater”, on the Theater at the Amistad Research Center website, the leaders stated their objectives in a document that laid the foundation for the FST. In “A General Prospectus for the Establishment of a Free Southern Theater”, the leaders affirmed, “Our fundamental objective is to stimulate creative and reflective thought among Negroes in Mississippi and other Southern states by the establishment of a legitimate theater, thereby providing the opportunity in the theater and the associate art forms. We theorize that within the Southern situation a theatrical form and style can be developed that is as unique to the Negro people as the origin of blues and jazz. A combination of art and social awareness can evolve into plays written for a Negro audience, which relate to the problems within the Negro himself, and within the Negro community.”

Early on, Moses, O’Neal and Derby knew they needed assistance to successfully establish their new Theater troupe and sought guidance from Richard Schechner, a professor at Tulane University. Schechner would serve in several roles, from Theater management advisor, producing director and chair of the FST’s Board of Directors.

The Free Southern Theater, originally comprised of three Black and five White actors, performed plays by celebrated persons such as James Baldwin, Samuel Beckett, Ossie Davis, Langston Hughes and John O. Killens. The organization toured primarily in rural areas of Louisiana and Mississippi, performing in Freedom schools, churches and outside stages. By 1965, the company had expanded to include twenty-three members, including an administrative staff and actors Roscoe Orman (Willie Dynamite, Sesame Street) and Denise Nicholas (Blacula, Let’s Do It Again and In the Heat of the Night television series), a future wife of Moses. Recalling their venues, stated on Amistad Research Center, Nicholas recalled performing in a to-be-completed community center in Mileston, Mississippi; the original had been bombed by White domestic terrorists. With the stage extending into nearby cotton fields, she reminisced, “Half the roof was there, the posts were there but the walls were not up yet … it was incredible and beautiful.”

Within a year, FST had to face certain realities if they were to remain viable. Though the reasons were noble, it was practically impossible to manage a “free” Theater. Constantly suffering financial struggles, the Theater was always on the brink of bankruptcy. As such, its members were consistently in aggressive modes of fundraising, whether it was applying for grants from organizations such as the Ford Foundation or receiving funds from philanthropists including Arthur Ashe, Harry Belafonte, Dr. Bill Cosby and Fannie Lou Hamer.

The company also moved to New Orleans, hoping to gain support from the city’s rapidly-growing, Black middle class. Yet this move was controversial, as some members felt this type of support countered the original mission of developing culture and social activism for the rural poor within their own communities. Several members, including founders Gilbert Moses and John O’Neal, left the FST.

In order to move forward in new directions, Black poet and writer Tom Dent moved to New Orleans to assume leadership. With the assistance of Val Ferdinand (later known as Kalamu ya salaam), Dent guided the creation and implementation of BLKARTSOUTH workshops. In the workshops, as stated on the Amistad Research Center website, “members began to write and produce scripts which were incorporated into the company’s repertoire.” Also special about these workshops was that they were available to all of those community members who never thought they would see themselves perform, whether acting, dancing, singing,

By 1966, all the actors in the Free Southern Theater were Black and primarily plays, such as Purlie Victorious, by Black playwrights were performed. These plays were created by those who were well-known, such as LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka), and those written by members of FST. These changes reflected a new sentiment of Black nationalism.

The Freedom Southern Theater also adapted plays by non-Blacks, building upon themes of the human condition to which many Blacks in the rural South could relate. They famously converted Martin Duberman’s In White America to recount the murders of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman. These three young men, 1 Black (Chaney) and 2 White, were field workers for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) who were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. The FST also performed Samuel Beckett’s acclaimed Waiting for Godot … but in whiteface.

As the years passed, the company continued to struggle and by 1980, the Free Southern Theater closed. However, John O’Neal formed his own Theater company, Junebug Productions, to carry on the mission and build upon the work of the FST. In 1985, O’Neal organized A Funeral for the Free Southern Theater: A Valedictorian Without Mourning, which included a New Orleans second line jazz funeral procession and three-day symposium to honor and celebrate the legacy of the Theater.

Junebug Productions continues to engage communities in the rural South, bringing Theater arts to those who are in the greatest need of it. One of its most significant endeavors is the National Color Line Project. Traveling the country to collect narratives and materials involving the Civil Rights Movement, Junebug Productions uses these to both archive history and apply content to greater understand contemporary race relations in the United States.