“Mrs. Hamer rose majestically to her feet … her magnificent voice rolled through the chapel as she enlisted the Biblical ranks of martyrs and heroes to summon these folk to the Freedom banner. Her mounting, rolling battery of quotations and allusions from the Old and New Testaments stunned the audience with its thunder.”

~ Tracy Sugarman, journalist, volunteer of Freedom Summer

Born on October 6, 1917, Fannie Lou was the last of twenty children born to her parents, James and Lou Ella Townsend. Residing in Montgomery County, Mississippi, her parents worked as sharecroppers. When she was two years old, her family moved to Sunflower County, Mississippi, where they continued to sharecrop. They labored on the plantation of W.D. Marlowe; the plantation was near Ruleville, Mississippi. At the age of six years old, she would join her parents and siblings in picking cotton. Even though a bout with polio left her physically handicapped, she, by the age of thirteen, picked between two hundred to three hundred pounds of cotton every day.

An extremely bright girl, she loved to learn and read. From 1924 to 1930, Fannie Lou was able to attend the one-room schoolhouse that children of sharecroppers attended during the winters, when the picking season was over. Her time of being formally educated ended when she was twelve years old because she had to assist in taking care of her parents.

Fannie Lou was able to further develop her learning by participating in the classes and study time at the church in which she was a member. In 1944, Marlowe learned that she was literate and she was promoted to be the time and record keeper on the plantation. During this time, she was being courted by Perry “Pap” Hamer, a tractor driver on the plantation. Marrying in 1945, the Hamer couple continued to labor on the Marlowe plantation until 1963.

During their marriage, Fannie Lou was unable to carry any of her pregnancies full-term. In 1961, Hamer was hospitalized in North Sunflower County Hospital for a minor surgical procedure to remove a tumor on her uterus. However, the White surgeon performed a total hysterectomy … without her permission. This forced sterilization and violation of Black women was a means in which Whites were reducing the Black population. It became so common in Hamer’s home state that the sterilization was referenced as a “Mississippi appendectomy”. According to her biography stub on the American Experience website, Hamer stated to a listening audience in Washington, D.C. in 1964 that “… I would say that six out of ten Negro women that go to the hospital are sterilized with tubes tied.” The Hamers would adopt two girls as their daughters because their own families were unable to care for them in such difficult times. They also later adopted their two grandchildren after their oldest daughter passed away.

The forced sterilization and violation of Black women, especially in the rural South prompted Fannie Lou Hamer to become politically active. Upon hearing Black leaders discuss issues, including voting, health and fair pay, that impacted the Black community at regional conferences, Fannie Lou Hamer became highly interested in securing civil rights, especially voting rights, for Blacks.

Learning from volunteers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) that Blacks had a constitutional right to vote, on August 31, 1962, she and seventeen of her neighbors took a bus from Ruleville, Mississippi, attempting to register to vote. In her own words, Hamer stated that they had “… traveled twenty-six miles to the county courthouse in Indianola to try to register to become first-class citizens. We was met in Indianola by policemen, highway patrolmen and they only allowed two of us in to take the literacy test at the time.”

She and a gentleman who were “allowed” to take the test failed. What is tragic is that Hamer and others in her circle had only recently learned of their constitutional right to vote. The right to vote, which is federal, was guaranteed with the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1870 … almost a century of rights denied! Literacy tests, like the grandfather clause (you could vote if your grandfather voted) and poll taxes, were illegal and unfair tactics implemented at local and state levels to bar Blacks from being able to vote, thus, be politically active.

When the group was returning to Ruleville, the police stopped the bus, harassing the passengers. They fined the driver $100, stating that the bus was “too yellow”. While being detained, Hamer led the other riders in singing spirituals, notably, “Go Tell It on the Mountain” and “This Little Light of Mine.” Her powerful singing of gospel songs became a signature action of Hamer’s to inspire and strengthen others in their battle for justice. Lawrence Guyot, Jr. spoke of Hamer’s power in A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow authored by David L. Chappell. In it, the civil rights activist and director of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) stated that he “admired her ability to connect ‘the biblical exhortations for liberation and [the struggle for civil rights] any time that she wanted to and move in and out to any frames of reference’”.

After scrambling to collect the monies, the driver was freed and allowed to drive Hamer and the others to Ruleville. Upon their return, Marlowe demanded and threatened that she had better withdraw her application to register for the franchise. She refused, stating in a refrain that she often said in her speeches, “I didn’t go down there to register for you. I went down to register for myself.” She was immediately fired and ordered off the plantation. However, Pap was forced to remain working and living on the land tract until the end of harvest in order to pay off the family’s sharecropping debt. For the sake of safety, over the next several days Fannie Lou stayed between the homes of loved ones and supporters in Ruleville. On September 10, sixteen shots, intended for Fannie Lou, from a moving vehicle were fired into the home of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Tucker. Knowing that these shots were from domestic White terrorists, such as the Ku Klux Klan, Pap moved his wife and their daughters to stay with relatives in Tallahatchie County, where they remained for almost three months. During this time, Fannie Lou stated that Marlowe had taken the Hamer vehicle and many of the items in the home they rented from Marlowe had been stolen. When the Hamer family moved to Ruleville, they had little material possessions.

Fannie Lou Hamer’s personality and perseverance caught the attention of Robert Moses, the field secretary of SNCC. Seeing her incredible potential as a community organizer, in 1962, Hamer was invited to Nashville, Tennessee for a conference of the organization that was held at Fisk University, a historically Black institution of higher learning. Hamer was a success and hired by SNCC, who paid her a weekly stipend of $10. As a community organizer for SNCC, she worked to de-segregate public accommodations, educate others on the need for active political involvement and register Blacks to vote. According to the American Experience site, Fannie Lou Hamer became “involved in relief work, distributing donated food and clothes to the poorest Delta residents. Hamer had spent her entire life in poverty, and she understood that the fight for economic security was a crucial component of the Civil Rights movement. At the same time, she was willing to use the donations as leverage, and sometimes refused to hand over food until the recipients agreed to register to vote.”

In December, the Hamer family returned to Montgomery County, Mississippi and she returned to Indianola to take the literacy test. Again, she was unsuccessful but told the registrar that she would be returning every month until she passed the test. On her third attempt, Fannie Lou Hamer passed and was registered as a voter in the state of Mississippi. However, she was not allowed to vote as she did not have receipts for two poll taxes. She later paid the illegal poll taxes in order to vote.

On June 9, 1963, Hamer, working as a field secretary for SNCC, and several other African-American activists were arrested in Winona, Mississippi for sitting in a bus station restaurant area reserved for Whites only. She and the others had recently returned from a citizen training workshop hosted by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Charleston, South Carolina. The group was refused service and law enforcement was called. A Mississippi State highway patrol officer threatened the group with his billy club, forcing them to leave. When one of the members in the group recorded the license plate of the officer, that officer, accompanied by the chief of the local police, arrested six of the activists.

When Hamer questioned the men, asking if those on the bus could return to Greenwood, Mississippi, she was arrested. While detained in the county jail, the activists, including June Johnson, a fifteen-year girl, were brutally battered by the police. Johnson was beaten for not including “sir” in her responses to the officers. One activist was bashed, rendering them unable to speak, and another, also a teen, was stripped and stomped.

Officers took Hamer to a cell where they physically restrained her. Then a Mississippi State trooper forced two Black inmates to pummel her with a blackjack. Her attempts to resist and protect herself were futile; additionally, an officer, pulling her dress over her shoulders, exposed her to five White men who repeatedly molested her. When SNCC had not heard from Hamer and the others, it sent Guyot, Jr., who represented the organization, to check on them. He was summarily beaten to the point that his eyes were swollen shut because he did not pay them the “proper” respect.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Three days later, on June 12, Fannie Lou Hamer and the others were finally released. Upon leaving, Reverend James Bevel informed Hamer and the others that on June 11, Medgar Evers was murdered on the front steps of his home in Jackson, Mississippi. Evers, the field secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), had been on a mission to integrate the University of Mississippi. The psychological and physical stress of her efforts did not deter Hamer from her activism. Having suffered numerous injuries, including a blood clot above her left eye as well as permanent damage to a kidney and to a leg, she continued to organize drives to register Blacks in her home state to vote and was integral to the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project, commonly known as the “Freedom Summer” initiative.

Also, in 1964, Fannie Lou Hamer co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which rivaled the local division of the all-White, pro-segregation Democratic Party. The Democratic Party, the dominant political party of Mississippi, refused to allow Blacks to participate. That year, Hamer, representing the MFDP, chose to run against Congressman Jamie Whitten in the Democratic primary. Although she was unsuccessful against the veteran politician of the Democratic Party, Fannie Lou Hamer accomplished two goals: she challenged the racist political system, including policies and practices, of Mississippi’s congressional delegation and created a national platform for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Inspired by the vision and courage of Fannie Lou Hamer and other members of the MFDP, hundreds of Black and White university students descended on Mississippi to advance civil rights during Freedom Summer. The primary focus was to register Blacks to vote in the segregated South. Many of these college students were from the North and some were White; as such, some Black, southern civil rights activists were hesitant to accept their involvement. Hamer felt that these young people were valuable to de-segregation and that to segregate themselves from those who are trying to help them was unwise and unfair.

In order to create a delegation representative of all people, free from discrimination and exploitation, the MFDP held conventions at the local, county and state levels. In August 1964, Hamer and members of the MFDP attended the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, demanding to be recognized as the official delegation. The integrated delegation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party consisted of four White members and sixty-four Black members, including Hamer, who was elected vice-president.

Their aim was to convince the convention’s Credentials Committee to seat them to represent Mississippi. As such, members of the MFDP testified before the committee. However, President Lyndon B. Johnson, a Southerner who needed the support of the Southerner-dominated Democrat Party for his bid to be re-elected, sought to block them from being seen on the televised hearings. When Hamer called for mandatory integrated state delegations, Johnson held an emergency press conference, prompting all the television broadcasting companies to cover him instead of Hamer.

However, Fannie Lou Hamer’s powerful testimony, vividly and painfully describing the racial prejudice and discrimination Blacks suffered in Mississippi, was so riveting that many news programs featured it that same evening. The president’s plan had backfired, actually garnering her a much larger audience than those who might have initially viewed the hearing. Speaking for approximately ten minutes, her accounts, including being evicted from the Marlowe plantation and being viciously assaulted in the Winona jail cell, shocked and appalled many viewers. Hamer concluded her testimony with her famous words, “If the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

(No copyright infringement intended).

While some on the Credentials Committee agreed with the stance of Hamer and the MFDP, they, ultimately succumbed to the pressure of the president. Democrat Senator Hubert Humphrey (Minnesota) proposed a compromise of offering two seats to the MFDP. However, the compromise came with the condition from the president that she be refused either seat, as there was no way that he would have Hamer, to whom Johnson referred as “that illiterate woman”, speak on the floor of the Democratic convention. The MFDP resoundingly and loudly refused the “offer” and all of the White members of the Mississippi delegation walked out.

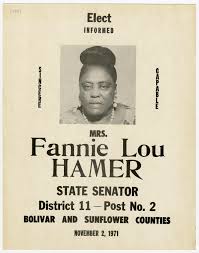

Fannie Lou Hamer attempted to run for the House of Representatives but was barred from the ballot. The following year, 1965, Hamer, Annie Devine and Victoria Gray became the first Black women to stand in U.S. Congress when they protested the Mississippi House Election, which excluded Hamer. The women were unsuccessful in their protest. However, Hamer continued her fight for civil rights, traveling across the country spreading her message. In 1968, the Democratic Party adopted a clause that allowed for racial parity and equality of representation in their states’ delegations, an aim of Hamer and the MFDP. In 1972, Fannie Lou Hamer unsuccessfully ran for a Senate seat but was elected as a delegate to the Democratic Party.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Since the televised committee hearings, Hamer was becoming extremely popular and though in high demand to speak throughout the United States, she still managed to remain focused on improving life in Mississippi. After the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, Hamer filed lawsuits that led to the first elections (1967) in Sunflower County in which a large number of Blacks were able to vote. Hamer also organized Black citizens to file lawsuits in order to desegregate public schools. She was actively involved in the Head Start program, which was created to bridge the educational barriers often experienced by low-income children of all races, as well as the Poor People’s Campaign of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1971, Hamer helped to create the National Women’s Political Caucus, an organization that empowered women, regardless of race or ethnicity, to become politically involved. However, she had become exhausted at dealing with the corruptness of politics and transitioned to economics in order to attain greater equality for Blacks. Many Whites, including politicians, wanted to retain exclusion and disenfranchisement of Blacks in every industry; the agricultural sector was no exception. To attain economic power and financial independence, in 1968, Hamer started a “pig bank”, in which Black farmers were gifted pigs to raise, breed and slaughter. Within five years, the pig bank had raised thousands of pigs.

Fannie Lou Hamer developed livestock and agricultural co-operatives in order to increase the economic independence of Blacks throughout the Delta. She learned this lesson at an early age, as she recalled in her speech, “Until I Am Free, You are Not Free Either.” When Fannie Lou was about thirteen years old, her parents were able to have saved a small amount of money to buy livestock in order to improve their lives beyond their meager subsistence. After purchasing three mules, Ella, Bird and Henry, and two cows, Maude and Della, a local White man poisoned the animals, killing them and the hopes of Hamer’s parents. In 1969, the Freedom Farm Cooperative (FCC) was created to purchase land that Blacks could collectively own and farm. Having collected $65, 500 in donations from sponsors, including the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) and actor/activist Harry Belafonte, Fannie Lou Hamer, ultimately, purchased 680 acres of land.

(No copyright infringement intended).

On the land, according to writer Monica M. White in her essay, “A Pig and a Garden: Fannie Lou Hamer and the Freedom Farms Cooperative” in Food and Foodways, were “a pig bank, Head Start program, community gardens, commercial kitchen, a garment factory, sewing cooperative, tool bank, and low-income, affordable housing as strategies to support the needs of African Americans who were fired and evicted for exercising the right to vote. Freedom Farms offered these sharecroppers and tenant farmers educational and retraining opportunities including health care and disaster relief for those who wanted to stay in the Mississippi Delta”. With this farm, Hamer and those at the FCC could meet three purposes, according to White: “These were to establish an agricultural organization that could supplement the nutritional needs of America’s most disenfranchised people; to provide acceptable housing development; and to create an entrepreneurial business incubator that would provide resources for new companies and re-training for those with limited education but manual labor experience.” The only qualification that a person had to have was to be poor, regardless of color or age.

The FCC continued to expand its outreach to Blacks throughout Mississippi and incorporated various services and programs, including financial literacy and scholarships. However, at this stage in her life, Hamer was becoming increasingly ill; in 1972, she was hospitalized for nervous exhaustion and in 1974 for a nervous breakdown. In 1975, the FFC disbanded due to lack of financial support. The following year, Hamer was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent a mastectomy.

On March 14, 1977, at the age of fifty-nine years old, Fannie Lou Hamer passed away at Taborian Hospital in Mound Bayou, Mississippi; the causes were complications post-breast cancer and hypertension. Obviously, other factors, including the violent assault against her in 1963 and an arduous lifetime of poverty, added in the diminished quality of life she had. Her primary memorial service was attended by more than fifteen hundred people, included Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Ella Baker of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Dorothy Height of the National Council of Negro Women.

(No copyright infringement intended).

The legacy of Fannie Lou Hamer was immense, during her lifetime and after her passing. She was admired by many, including Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali. She was awarded a doctorate from Shaw University and honorary degrees from Howard University and Columbia College in Chicago. She received numerous awards, including the Paul Robeson Award and the Mary Church Terrell Award, by, respectively, the Black sororities, Alpha Kappa Alpha and Delta Sigma Theta; from the latter organization, she was awarded an honorary lifetime membership. The 2019 Women’s March, held in Atlantic City, New Jersey, was dedicated to the life and legacy of Fannie Lou Hamer.

There are monuments and schools across America named in her honor and, through Congressional order, the post office in Ruleville, Mississippi is named the Fannie Lou Hamer U.S. Post Office. In Jackson, Mississippi, there is a public library as well as educational center named in tribute of her. Located on the campus of the historically Black institution of higher learning, Jackson State University, is The Fannie Lou Hamer Institute @ COFO (Council of Federated Organizations): A Human and Civil Rights Interdisciplinary Education Center. It contains a research library and develops community outreach programming. Also, on a college campus is the Fannie Lou Hamer Black Resource Center at the University of California at Berkeley.

Hamer is the subject of the musical suite, “Fannie Lou Hamer and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, 1964”. It is one of the nineteen suites that comprised the four-disc box-set, Ten Freedom Summers, released in 2012. Composed by trumpeter, Wadada Leo Smith, who was reared in segregated Mississippi, the compositions were created over a thirty-four-year period, 1977-2011.

Coretta King Award-winning author Carol Boston Weatherford wrote Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement, a picture book for children.

“Sometimes it seem like to tell the truth today is to run the risk of being killed. But if I fall, I’ll fall five feet four inches forward in the fight for freedom. I’m not backing off.”

~ Fannie Lou Hamer

For greater enlightenment...

-

Fannie Lou Hamer: Stand Up/MPB

-

The Heritage of Slavery (1968) w/Fannie Lou Hamer & Lerone Bennett, Jr.

-

Fannie Lou Hamer – “Until I am Free You Are Not Free Either”

-

We’ll Never Turn Back (1963)/SNCC Film feat. Fannie Lou Hamer

-

SNCC,the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and Lyndon Johnson (LBJ)

-

Malcolm X opens for Fannie Lou Hamer 1964