“(Dorothy) Porter must be acknowledged for her efforts to address the marginalization of writing by and about black people through her revision of the Dewey system as well as for her promotion of those writings though a collection at an institution dedicated to highlighting its value by showing the centrality of that knowledge to all fields.”

~ Zita Cristina Nunes, Journalist

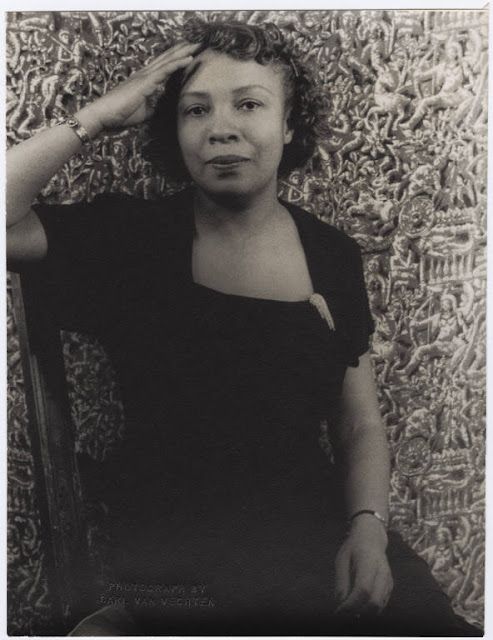

On May 25, 1905, in Warrenton Virginia, Hayes Joseph and Bertha (née Ball) Burnett welcomed their first child, a daughter, who they named Dorothy Louise. The family would soon move to a predominately White-populated neighborhood in Montclair, New Jersey. Hayes, a physician, and Bertha, a tennis champion who was essential in the creation of the New Jersey Tennis Association, emphasized the value and importance of education to Dorothy and her three siblings. Having attended racially-mixed public schools, in 1923, Dorothy entered Minor Normal School in Washington, D.C. Burnett selected to attend Minor Normal School after her graduation from high school because the institution was renowned for educating African-American women, especially in training them to enter the field of teaching.

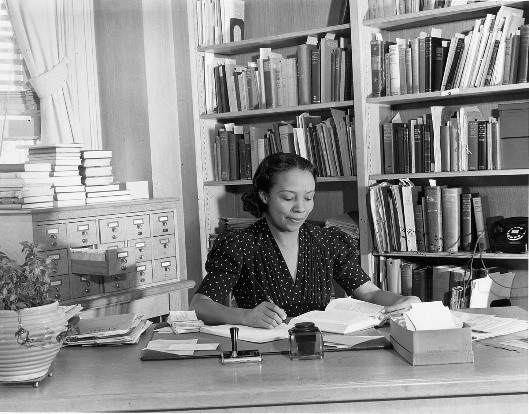

During her time of study at Miner Normal School, Dorothy, a bibliophile, was presented with an opportunity that would prompt her to abandon a future career as a teacher. In 1925, her spur-of-the-moment decision to briefly substitute for a librarian who was out on sick leave transformed what the rest of her life. The substitution developed into a year-long assignment and it greatly inspired her to seek a career in library science.

In 1926, Dorothy Burnett transferred to Howard University, a historically Black university located in Washington, D.C. After earning her Bachelor of Arts from Howard University in 1928, she joined the library staff at Howard. She also matriculated graduate school at Columbia University in the City of New York, an Ivy League university.

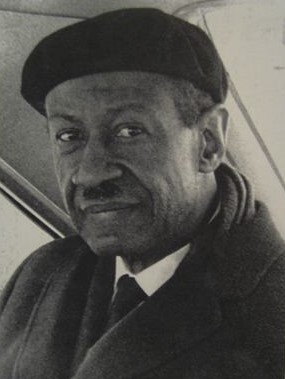

While at Columbia University, she attained a position as a librarian at the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library, presently known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. While working at the esteemed library branch that focused on Africa Diaspora culture, she met artist James A. Porter. Porter was conducting research on African-American artists who had been overlooked and/or omitted from American history and culture. Building beyond their professional interests, Porter courted Burnett.

(No copyright infringement intended).

On December 27, 1929, James Amos Porter and Dorothy Louise Burnette were married and they would have a daughter, Constance. For the rest of their lives, the couple was highly supportive of and heavily involved in each other’s work and research. This was beneficial, personally and professionally, as James later served as the chair of the art department and head of the Art Gallery of Howard University. He is perhaps best known as the “Father of African-American art history.”

In 1930, Dorothy Porter, as she became professionally known, was appointed by W. Mordecai Johnson, president of Howard University to organize and oversee the administration of a library dedicated to African American life and history. At the foundation of this new organization and administration was the private collection of Rev. Dr. Jesse E. Moorland, an alumnus and trustee of Howard University and secretary of the Washington, D.C. branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Moorland also was the co-founder of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH), currently known as the Association for the Study of African-American Life and History (ASALH). Moorland was persuaded by Howard alumnus Kelly Miller, a highly-regarded African-American intellectual, to donate his collection to Howard for its proposed “Negro-Americana Museum and Library.” Known as the “Bard of the Potomac”, Miller served as the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.

The contents of the library, which primarily focused on slavery and abolition, were greatly expanded with Moorland’s 1915 gift of more than three thousand items. Considered to be one of the most critical collections of Black culture-related materials, his magnanimous gift illustrated African Americans’ efforts to create, curate, collect, preserve and disseminate their own culture, including history. This collection at Howard University’s library opened in 1933 and was collectively known as The Moorland Foundation.

In 1931, Dorothy Porter completed a Bachelor of Arts degree in library science at Columbia. In 1932, she earned her Master of Science degree, becoming the first African-American woman to earn a graduate degree in library science from Columbia University in the City of New York.

In leading The Moorland Foundation, Porter worked diligently to establish sincere relationships with book dealers and publishers in order to further expand the collection on Black culture. In the article Zita Cristina Nunes wrote in “Remembering the Howard University Librarian Who Decolonized the Way Books Were Catalogued” for American Historical Association’s Perspectives on History, Nunes recounted an oral interview Porter had with Avril Johnson Madison. Beseeching bookstore owners and publishing companies, Porter stated, “I think one of the best things I could have done was to become friends with book dealers … I had no money, but I became friendly with them. I got their catalogs, and I remember many of them giving me books, you see. I appealed to publishers, ‘We have no money, but will you give us this book?’”

The network of connections that Dorothy Porter created to further develop The Moorland Foundation was global. It also involved her friends, including Dorothy Peterson, Alain Locke and Langston Hughes, who advocated others on her behalf. Because of her international outreach, the collection is global and contains materials in different languages. The Moorland Foundation provided more thorough and accurate accounts and creations by and about Black people worldwide. Because of her efforts, the collections at Howard’s library, as discussed by Nunes, included music compositions by “Antônio Carlos Gomes and José Mauricio Nunes Garcia of Brazil; Justin Elie of Haiti; Amadeo Roldán of Cuba; and Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges of Guadeloupe. The linguistics subject area includes a character chart created by Thomas Narven Lewis, a Liberian medical doctor, who adapted the basic script of the Bassa language into one that could be accommodated by a printing machine. (This project threatened British authorities in Liberia, who had authorized only the English language to be taught in an attempt to quell anti-colonial activism). Among the works available in African languages is the rare Otieno Jarieko, an illustrated book on sustainable agriculture by Barack H. Obama, father of the former U.S. president.”

This image is sourced from Pinterest

(No copyright infringement intended).

In expanding the Foundation to be more representative of the Africa Diaspora, she also invited pan-Africanist political leaders, such as Kwame Nkrumah and scholars, such as Brazilian historian Edison Carneiro to visit Howard University. In the Madison oral interview, Porter stated, “… At that time … students weren’t interested in their African heritage. They weren’t interested in Africa or the Caribbean. They were really more interested in being like the White person.”

In 1946, Howard University acquired the private collection of attorney Arthur B. Spingarn, chair of the legal committee of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). A bibliophile of grand proportions, Spingarn had curated a collection of approximately five thousand volumes called the Negro Authors Collection. Highly interested in the Africa Diaspora experience, Spingarn’s collection, as Nunes detailed, “…included works by and about Black people in the Caribbean and South and Central America; rare materials in Latin from the early modern period; and works in Portuguese, Spanish, French, German, and many African languages, including Swahili, Kikuyu, Zulu, Yoruba, Vai, Ewe, Luganda, Ga, Sotho, Amharic, Hausa, Xhosa, and Luo. These two acquisitions formed the backbone of the Moorland Spingarn collections.”

In acquiring materials, there are values, cultural, political, intellectual and financial, that can be assigned. The collection of Arthur B. Spingarn was no different, and the treasurer of Howard University insisted that it be financially appraised by an external assessor. The treasurer did not want to rely on Dorothy Porter, a Black woman, and was adamant about obtaining its value assessed elsewhere. She sought an appraiser from the Library of Congress. However, that appraiser, having no professional experience in evaluating Black books and materials. He asked Porter to evaluate the collection and compose the report, to which he would sign and send it to the treasurer. The treasurer, believing it was the work of a White colleague, accepted Porter’s appraisal. Her report created the standard in appraising collections of books that centered on Black culture.

In 1958, the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, as it had become known, purchased the Negro Music Collection of Arthur Spingarn. At that time, this collection was the largest of its kind in the world.

Perhaps what was one of the greatest professional accomplishments of Dorothy Porter was her development of a new system to catalog the content of the collections. Building upon the work of librarians Lula V. Allen, Edith Brown, Lula E. Connor and Rosa C. Hershaw, who had previously worked at Howard University, Porter elected to classify content by genre and author. Dismissing the Dewey Decimal Classification system, she categorized materials in order to illuminate the massive contributions and pervasive roles of Black people in subject she designated as art, anthropology, communications, demography, economics, education, geography, history, health, international relations, linguistics, literature, medicine, music, political science, sociology, sports, and religion. This new categorization would challenge racist stereotypes and lies by presenting works by and about Black people within their appropriate areas of accomplishment and academic scholarship.

During the 1963-1964 academic year, Dorothy’s husband, James, traveled overseas for what would be his final educational trip. Sponsored by a grant of the Evening Star, a newspaper in Washington, D.C., the Porters toured West Africa and Egypt. The West African countries they visited included Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo. Their research, which consisted of museum visits, personal interviews with artists and photographing more than eight-hundred works of art and architecture, furthered the academic and Africa Diaspora cultural growth at Howard University.

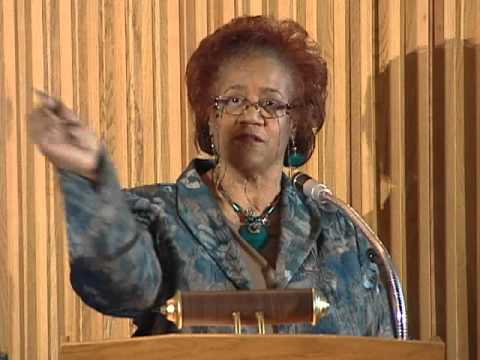

In 1970, James A. Porter passed away. In 1973, Dorothy Porter retired from leading the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center. Underneath her guidance, the center grew to contain more than 180,000 books, manuscripts, pamphlets and other primary resources. Porter was essential in developing the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center into one of the greatest collections of research materials for Africa Diaspora history and culture worldwide. In honor of her more than forty-three years of service, Howard University created the “Dorothy B. Porter Reading Room” and developed the annual Dorothy Porter Wesley Lecture Series.

During her retirement, Porter continued to research, write and publish materials centered upon Black cultural content.

(No copyright infringement intended).

On November 29, 1979, Dorothy Porter married again. Her new husband, Dr. Charles Wesley, shared her interests in Black culture and the advancement of Black people. The third African-American to earn his doctorate from Harvard University, Dr. Charles Wesley was a past president of Wilberforce University and the founding president of Central State University, historically Black institutions located in Wilberforce, Ohio. A minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church for more than four decades and an educator who also taught at Howard University, Wesley authored fifteen books on African-American history.

He edited the Journal of Negro Life and History of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASALH). Upon the retirement of his mentor, colleague and friend, Dr. Carter G. Woodson, the co-founder of ASNLH, Wesley served as the association’s Director of Research and Publications and its Executive Director from 1965 to 1972; he later became its Executive Director Emeritus. In 1976, he became Director of the Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; it is presently known as the African American Museum in Philadelphia. He would pass away in Washington, D.C. in 1987.

The diminishing health of Dorothy Porter Wesley caused her to move away from Washington, D.C., her home of more than seventy years. She settled in Broward County, Florida, where, on December 17, 1995, Dorothy Porter Wesley passed away from cancer; she was ninety years old.

For her extensive work in collecting and curating history of Black people, Dorothy Porter Wesley received numerous honors and awards. These accolades include the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, Ford Foundation research grants, the Distinguished Alumni Award from Howard University and a fellowship from the W.E.B. DuBois Institute at Harvard University. From 1962 to 1964, she served as a Ford Foundation consultant to the National Library in Lagos, Nigeria. She visited Accra, Ghana to participate in the 1st International Congress of Africanists. In 1980, the Conover-Porter Award, the most prestigious award for published works of bibliography or reference in Africa, was created in tribute to her pioneering work.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Having published many bibliographies and an anthology, Dorothy Porter Wesley received honorary doctorates from Susquehanna University, Syracuse University and Radcliffe College. She was also presented the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Charles Frankel Award by President Bill Clinton.

“The only rewarding thing for me is to bring to light information that no one knows. What’s the point of rehashing the same old thing?

~ Dorothy Porter Wesley