“It was like nothing you had ever seen … He gave us more than steps … Cholly gave us wisdom. He taught us how to touch an audience and about living life. He was Motown’s father figure.”

~ Duke Fakir, Member of The Four Tops

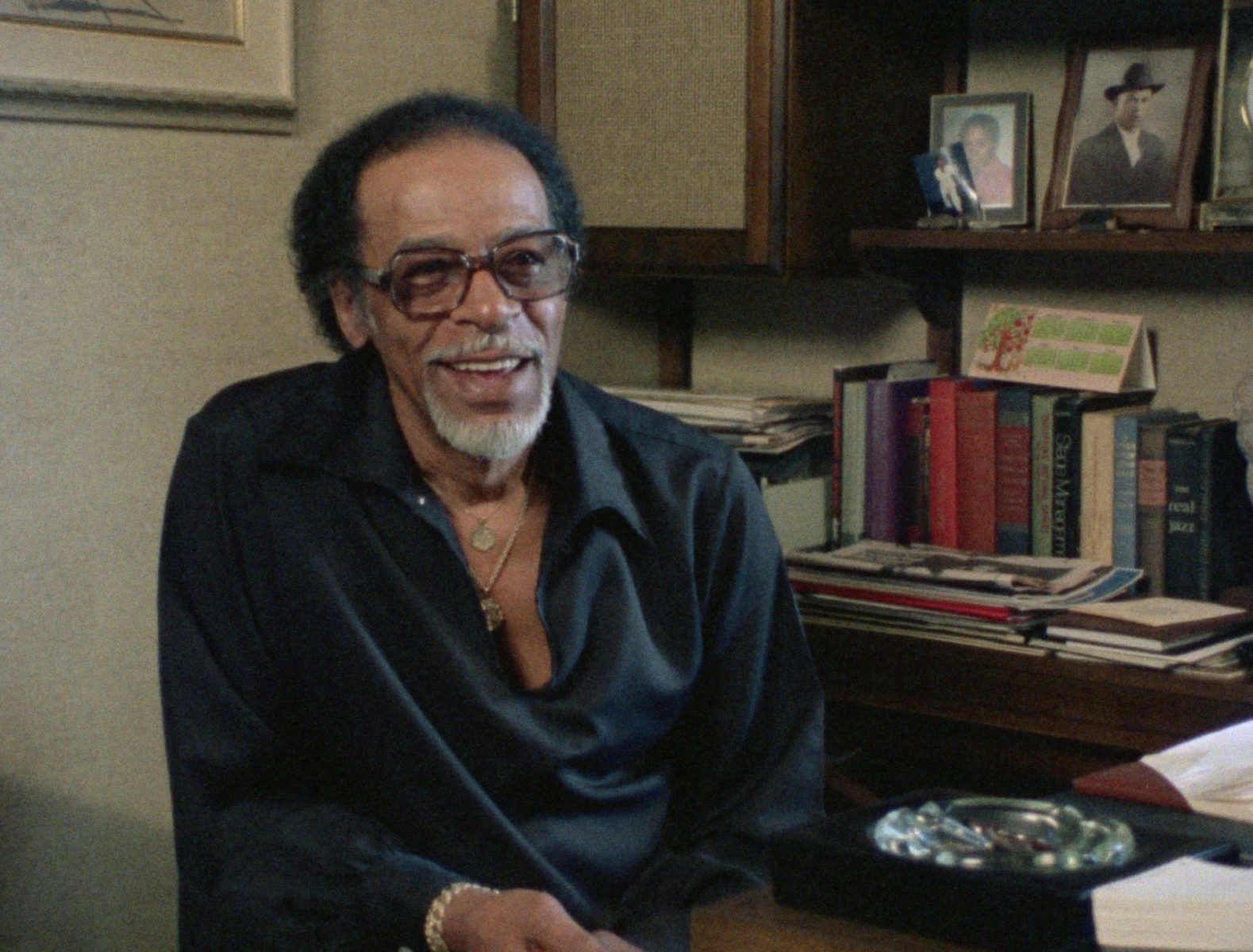

Charles Sylvan Atkinson was born on September 13, 1913 in Pratt City, Alabama to Christine Woods and Sylvan Atkinson. In 1920, his mother left the South with him and his brother, Spencer, to move to Buffalo, New York in search of better opportunities. Upon settling there, Charles soon became involved in the variety shows presented by his elementary physical education teacher and coach and winning local talent shows. His passion for performance ignited and by the time he entered secondary school, Charles was balancing his academics with extracurricular activities including sports and dancing.

When he was sixteen years, he accepted a position as a performing waiter at Alhambra on the Lake, a club outside Buffalo. This was his entry into the professional career of dancing and also marked his first performance partnership. Later linking up with fellow server, William Porter, they connected, calling themselves, “Two Rhythm Pals”. They added tap dance, including combinations, from a professional chorus line dancer, Katherine Davis.

By 1930, Atkinson and Porter, now known simply as “Rhythm Pals”, had begun traveling with various revues led by artists, such as Sammy Lewis and Stringbean Williams. These shows included acts by comedians, dancers, musicians and singers. During this decade, he befriended with many professional performers, including Charles “Honi” Coles, June Richmond, Dorothy “Dottie/Dotty” Saulters, Cab Calloway and Catherine Williams. Williams, a chorus girl at the famous Cotton Club, would become Charles Atkinson’s first wife in 1936.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Towards the end of the 1930s, the duo disbanded and Porter and Atkinson went separate ways. Atkinson began to choreograph and he landed what was the most significant position of his career at that time. He was hired to choreograph routines for the Cotton Club Boys, who accompanied dancing legend, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson in Hot Mikado at the 1939 World’s Fair held in New York City. His work with the Cotton Club Boys solidified Cotton Club bandleader Calloway and his revue to the limelight.

By 1941, Atkinson and Coles, who had long been friends and performed together, were hired to choreograph dance routines at the Club Paradise. Professionally, their acts reunited Atkinson and Saulters, who had married Coles in 1936. Coles was a debonair tap dancer whose grace “made butterflies look clumsy”, gushed legendary singer Lena Horne in “Charles ‘Honi’ Coles: Broadway Tap Dancer” by Burt Folkart in the Los Angeles Times.

Although she and Dotty performed in the troupe, Catherine soon found little work as a show dancer and left Harlem to settle in Chicago. In the meantime, Charles created a dancing duet with Dotty while Honi had his own solo acts with Calloway’s swing orchestra.

In 1942, Charles Atkinson entered the U.S. Army to serve during World War II. After completing his enlistment, he returned to dancing and even partnered with Saulters, who was known for her performances with Calloway. Together, they performed with musical greats, including Earl “Fatha” Hines and The Mills Brothers, and with collectives such as the Louis Armstrong Band. In 1943, Coles was drafted to serve in the army. With both of their spouses being away, before long, the professional relationship of Atkinson and Saulters turned personal. In 1944, Cholly and Dotty divorced their respective spouses and married each other.

Coles seemed to have accepted their marriage, as he, too, remarried that year, to elite tap dancer, Marion Edwards. Honi became the final and most enduring dance partner of Cholly’s. At this point, Charles became known as “Cholly Atkins.” The first name was taken from the moniker of Cholly Knickerbocker, a columnist with the New York Journal-American and the surname was abbreviated because it both sounded better professionally and it could fit on club marquees. They created their own act, “Coles and Atkins”. Considered to be the epitome of class, this duo performed with the bands of some of the greatest musicians in history. Among these esteemed artists were Count Basie, Billy Eckstein, Lionel Hampton and Johnny Otis.

Coles and Atkins also performed on stage, most notably in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes on Broadway from 1949 until 1952. Though the production’s choreographer Agnes DeMille did not credit the duo, their creation of “Mamie is Mimi” was acclaimed. They also choreographed routines for choreographers, including June Taylor and her dancers, whose performances were broadcasted on television.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

By the 1950s, however, tap dancing was seen through a negative lens due to its past derogatory association and exploitation of Blacks by Whites, especially in the media. Difficult to attain work, Coles and Atkins became solo artists.

R & B music was becoming more popular and Atkins was hired to choreograph dance routines for a musical group, the Cadillacs. For the next decade, he taught dancing to popular musical acts such as Little Anthony and the Imperials, the Moonglows, and the Shirelles. Typical of life, with the highs, come the lows. In 1960, his wife, Dotty, passed away from a brain tumor.

His work was so amazing that it caught the attention of the Miracles, a group on the rise signed to the Motown label in Detroit, Michigan. In “Cholly Atkins Dies at 89” by David Lyman for the Detroit Free Press, Bobby Rogers commented on the impact of Atkins. An original member of the Miracles, he recalled, “We had been to the Apollo about a year before we met Cholly and we didn’t have any choreography at all … We were just popping our fingers and moving our feet a little. The owner of the Apollo said, ‘I don’t want you guys back here ever again.’” The Apollo Theater, located in Harlem, was the premier venue for Black entertainers. With the success of “Shop Around”, the group hired Atkins in 1962 to guide them. Roger shared, “He worked us eight hours a day at his house on Buena Vista … He gave us a class that no one else in the country had.”

That same year he was hired by the Miracles, he met Maye Harrison, who became his third wife in 1963. Unlike Catherine and Dotty, she was not a dancer; Maye had a career at Macy’s.

In 1964, Motown founder Berry Gordy hired Cholly Atkins to be the choreographer for his musical acts. Atkins would be essential in creating what would be known as a golden era for the Detroit label. His precise and creative routines were accented by his signature smooth delivery. Atkins worked, via choreography, directing and staging, with The Supremes, Aretha Franklin, The Four Tops, The Marvelletes, Stevie Wonder, Gladys Knight & the Pips and Marvin Gaye until the 1980s. He is perhaps best known for his work with The Temptations. In fact, he is featured teaching them a routine in their 1986 video, “Lady Soul”. When Motown relocated to Los Angeles, the Atkins re-located to live in Las Vegas.

(No copyright infringement intended).

(No copyright infringement intended).

Despite the essentiality of Atkins to the success of the now-famous music label, many felt that he was not truly recognized for his immense contributions. In the Detroit Free Press article, Atkins’ wife divulged, “Motown never mentioned his name.” An example of this occurred for the televised 25th anniversary celebration of Motown. Maye told Lyman that her husband was supposed to introduce The Temptations. However, just four hours before the group’s performance, he was informed that he was being removed from the history-making tribute. She shared, “He never complained about it, but it broke his heart.”

Atkins also choreographed routines for artists, like the O’Jays, who were not on the Motown label. According to the biography on Atkins from the Library of Congress’ website, Cholly “taught them to perform with gestures, rhythmic dance steps and turns drawn from the rich bedrock of American vernacular dance and, in doing so, created a new form of expression called Vocal Choreography.”

In 1989, Atkins work on Broadway led to more than just being celebrated by the audience, as when he partnered with Honi Coles. Cholly Atkins won a Tony Award for his choreography on Black and Blue. In 1993, he was gifted the three year Choreographer’s Fellowship, the highest award of the National Endowment for the Arts. With it, he recorded accounts of his life and also toured universities throughout the United States, teaching his incredible creation, vocal choreography. He would continue to teach dance until his health would not allow him.

On April 19, 2003, Cholly Atkins passed away from pancreatic cancer that had just been diagnosed in February.

Ironically, Cholly Atkins never danced outside of work. In the Lyman article, Maye reflected on their first date. She shared, “We danced every dance that night. But after that we never did dance again. Come June, we would have been married 40 years. But he wouldn’t dance. ‘That’s my business … I don’t dance unless I get paid.’ I guess I should have paid him.”

The legacy of Cholly Atkins is felt by many worldwide and is sure to continue to endure. He was indeed a master of choreography, dancing, directing and teaching. Atkins was the recipient of the Living Treasure in American Dance Award from the Oklahoma City University School of American Dance and Arts Management in 1999. His memoir, Class Act: The Jazz Life of Cholly Atkins, was co-authored by Jacqui Malone and published in 2001.

(No copyright infringement intended).

As Brian Pastoria, a longtime friend of Atkins and partner in the Harmonie Park creative Group exclaimed in the Lyman article, “The Funk Brothers got to that point in ‘Stop! (In the Name of Love)’ – the point where the Supremes plant their feet and defiantly thrust their arms forward – nearly every person in the Detroit Opera House joined in with the choreography. ‘You saw 2,000 people doing a Cholly Atkins move … It was amazing!’”

“There’s a lot that goes into training singers to eventually become performers. There’s, projection … which in many cases the artist was never concerned about.”

~ Cholly Atkins

For greater enlightenment...

-

"Honi" Coles & "Cholly" Atkins: "Swing is Really The Thing" [HD]

-

Over the Top Be-Bop: Honi Coles & Cholly Atkins.

-

Honi Coles & Cholly Atkins with Leonard Reed 1955

-

Coles & Atkins -Taking a Chance on Love - Soft Shoe Dance

-

Honi Coles & Cholly Atkins 1955

-

The Temptations rehearsal w/ Cholly Atkins - Lady Soul (1986)