“… No lie is strong enough to kill

The roots that work below

From your rich dust and slaughtered will

A tree with tongues shall grow … ”

~ “In Memory of Colonel Charles Young” by Countee Cullen

Charles Young was born into slavery on March 12, 1864 to Gabriel Young and Arminta Bruen in Mays Lick, Kentucky, a small village near Maysville. His father escaped from slavery early in 1865, crossing the Ohio River to Ripley, Ohio, and enlisted in the Fifth Regiment of Colored Artillery (Heavy) near the end of the American Civil War. Gabriel’s service earned him and his wife their freedom, as guaranteed by the 13th Amendment after the war.

Young was the only “Colored” student who attended the all-White high school in Ripley. Upon graduating in 1880 at the top of his class, he taught school for several years in the new all-Black high school that was opened in Ripley. In 1884, Young entered U.S. Military Academy at West Point. There, he shared a room with John Hanks Alexander, who, in 1887, became the 2nd African-American to graduate from West Point. Young was repeatedly treated with excessive abuse by many of the students and faculty; he remained steadfast, despite the obvious racial discrimination and loneliness, graduating in 1889, with his commission as a 2nd Lieutenant.

(No copyright infringement intended).

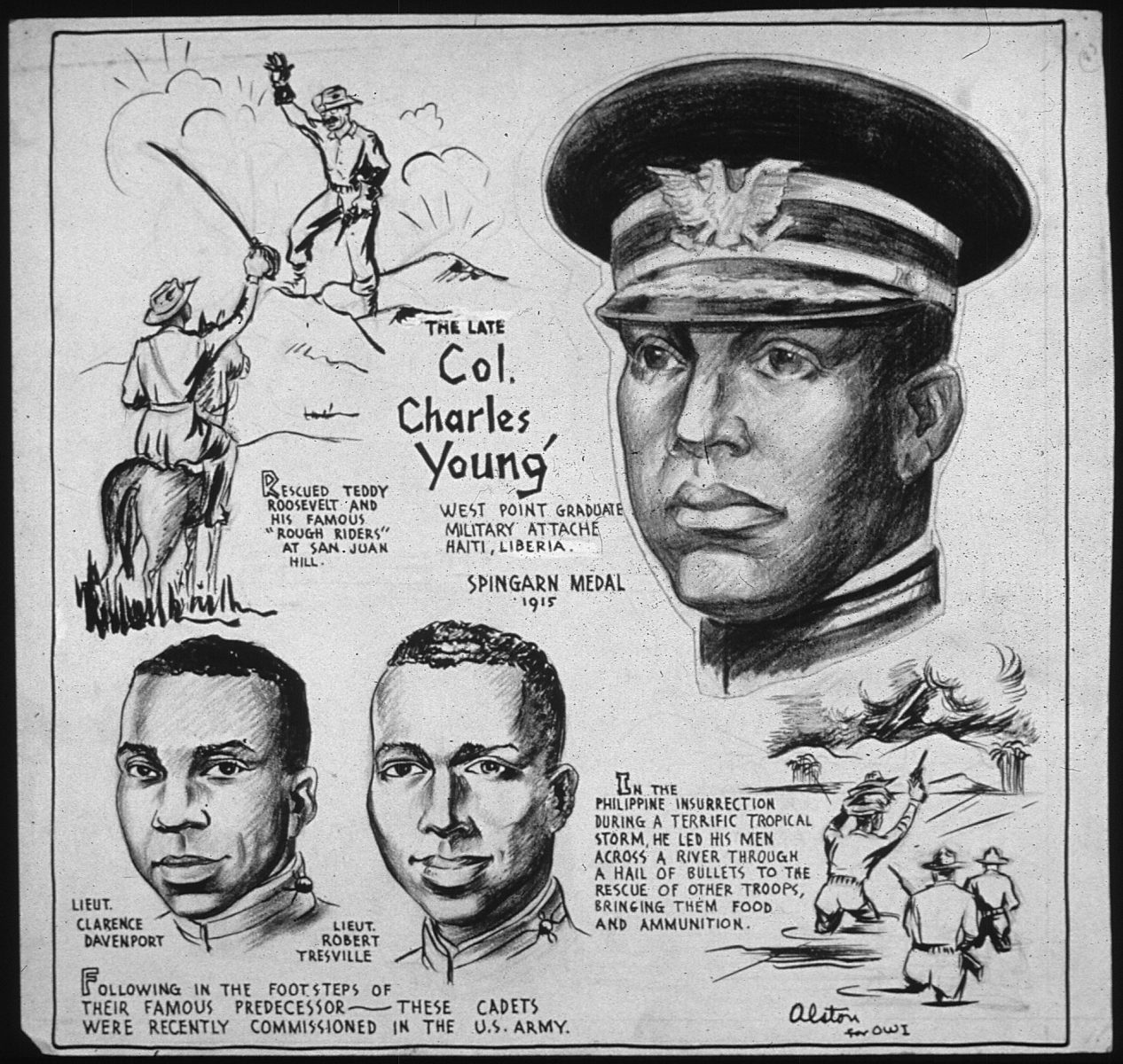

Young served in the 9th and 10th U.S. Calvary and later led these regiments. He served with these Buffalo Soldiers for the next 28 years. During this time, he married Ada Mills in 1904 and they had two children: Charles Noel, born in 1906 in Ohio, and Marie Aurelia, born in 1909 in the Philippines. Also, during this time in his military career, Young was assigned in 1894 to Wilberforce College in Ohio, an historically black college (HBCU). He led the new military sciences department, which was established under a special federal grant. A professor for four years, he was one of several outstanding members on faculty, which included W.E.B. DuBois. Young, DuBois and writer Paul Laurence Dunbar would become lifelong, close friends. In 1901, he was promoted to “Captain” after the Spanish-American War. A man of many talents, he played the piano, organ and violin; created art; composed music and authored books, including The Military Morale of Nations and Races.

(No copyright infringement intended).

In 1903, Young served as captain of a Black company at the Presidio of San Francisco, California. He was then appointed acting superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant national parks, thus, becoming the first Black superintendent of a national park.

Young’s greatest impact on national parks was managing road construction, which helped improve underdeveloped parks and allowed more visitors to enjoy them. Young’s contributions were highlighted in the Ken Burns’ The National Parks documentary series. In the segment, “Yosemite’s Buffalo Soldiers”, it’s stated that Young’s men accomplished more that summer than had been done under the three officers assigned to the park during the previous three summers combined! Captain Young’s troops completed a wagon road to the Giant Forest, home of the world’s largest trees, and a road to the base of the famous Moro Rock. By mid-August, according to the website of the National Park Service, the wagons of visitors could enter the mountaintop forest for the first time. Because of his efficacious leadership and fluency in speaking French, Spanish, German and several other languages, Young would serve as a military attaché in Haiti, Liberia and Nigeria.

During his lifetime, Colonel Charles Young received numerous honors and accolades. In 1912, Colonel Young became only the second honorary member of Omega Psi Phi fraternity, the first predominately African-American fraternity to be founded at a historically Black university (1911, Howard University). He also was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1916.

In 1917, with the United States about to enter World War I, Young was eligible to be promoted to “Brigadier General” because of his decorated military service and combat history. However, there was widespread resistance among White officers, especially those from the segregated South, who did not want to be outranked by a Black officer. Because of racial prejudice and discrimination, his ascension was constantly thwarted. The War Department instead removed Young from “Active Duty”, claiming it was due to his high blood pressure. Young, now given the rank of “Colonel”, was placed temporarily on the “Inactive” list on June 22, 1917.

In May 1917, Young appealed to former President Theodore Roosevelt for support of his application for reinstatement. Roosevelt immediately wrote to Young offering him command of one of the prospective regiments, according to Richard Slotkin in Lost Battalions: The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationality, stating ” … there is not another man [than yourself] who would be better fitted to command such a regiment.”. Roosevelt also promised Young carte blanche in appointing staff and line officers for the unit. However, President Woodrow Wilson refused Roosevelt permission to organize his volunteer division.

Young then returned to Wilberforce University, where he was a professor of military science through most of 1918. On November 6, 1918, after he, at 54 years old, traveled by horseback from Wilberforce, Ohio, to Washington, D.C. to prove his physical fitness, he was reinstated to “Active Duty” as a “Colonel”. Secretary of War Newton Baker refused to rescind his order that Young be forcibly retired and in 1919, Young was reassigned as military attaché to Liberia.

(No copyright infringement intended).

While on a reconnaissance mission in Nigeria, Young passed away on January 8, 1922 of a kidney infection in Nigeria. He was given a full military funeral and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Though he never personally received them, Colonel Charles Young was entitled to the following medals: Indian Campaign Medal, Spanish War Service Medal, Philippine Campaign Medal, Mexican Service Medal and the World War I Victory Medal.

(No copyright infringement intended).

Young has become a widely-respected, public figure because of his unique achievements in the Army and the National Parks Service. In 2013, President Barack Obama used the Antiquities Act to designate Young’s house in Wilberforce, Ohio as the 401st unit of the National Park System, “The Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument”. In 2018, legislation was passed in California to convert the name of California State Route 198 to “Colonel Charles Young Memorial Highway.” This is more than fitting, as Colonel Young served as superintendent of Sequoia National Park, which is located at the eastern end of the highway.

Living a life that was, as DuBois eulogized “a triumph of tragedy”, the inspiration and legacy of Colonel Charles Young has thrived in the Black men and women who, in 2017, comprise, respectively, 30 and 17 percent of active-duty military personnel in the U.S. Army!

Dates of Rank

*Cadet, United States Military Academy

June 15, 1884

*2nd Lieutenant, 10th Cavalry

August 31, 1889 (transferred to 9th Cavalry October 31, 1889)

*1st Lieutenant, 7th Cavalry

December 22, 1896 (transferred to 9th Cavalry October 1, 1897)

*Major (Volunteers), 9th Ohio Colored Infantry

May 14, 1898

Forced out of Volunteers

January 28 1899

*Captain, 9th Cavalry

February 2, 1901

*Major, 9th Cavalry

August 28, 1912 (transferred to 10th Cavalry October 19, 1915)

*Lieutenant Colonel

July 1, 1916

*Retired as Colonel

June 22, 1917