“Mrs. Charity Adams Earley is a most distinguished soldier, an educator, a wife, a mother and a much-honored citizen of Dayton, Ohio.”

~ Retired U.S. Army Brigadier General Evelyn P. Foote

In the last week of May, history was made at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point when it graduated 34 African-American women in its Class of 2019! Although the Class was comprised of more than 950 cadets, they represented the largest number of Black women to graduate from the premier military academy since its creation in 1802. Prior to the May 2019 graduation, there had never been more than 20 Black women to graduate from West Point.

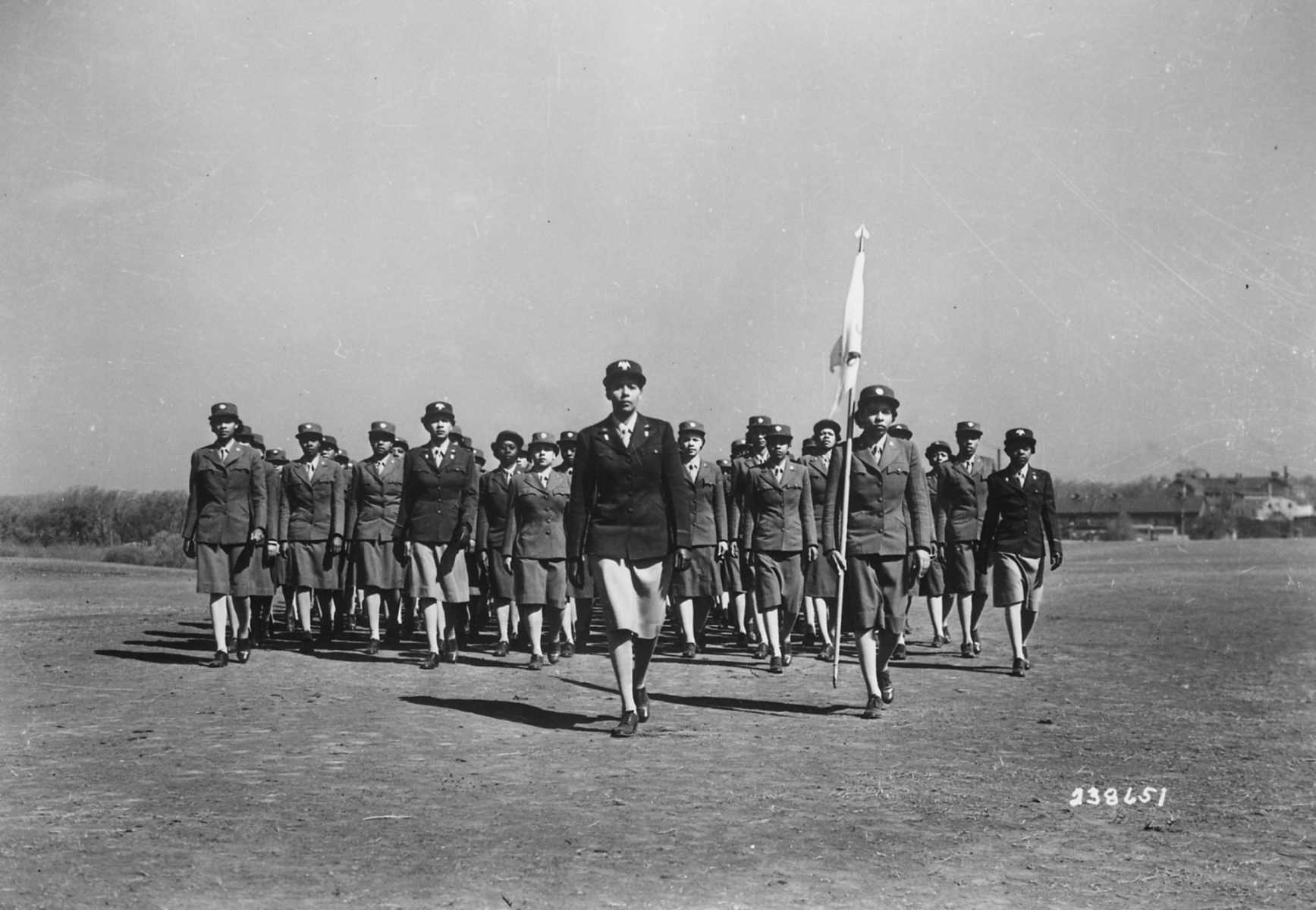

This accomplishment was made possible because of Black trailblazers such as Colonel Charles Young of the U.S. Army and Lieutenant Colonel Charity Adams Earley of the Women’s Army Corp of the U.S. Army. As the first African-American officer in the Women’s Army Corp (originally known as the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corp), she was assigned to be the commanding officer of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. This was the first battalion of African-American women, approximately 850, to serve internationally during World War II. At the end of the war, Earley, as a lieutenant colonel, was the highest ranking African-American woman in the Army.

Born Charity Edna Adams on December 5, 1918 in Kittrell, Vance, North Carolina, she was the daughter of Reverend Eugene and Charity Adams. As the oldest of 4 children, she understood the immense value of education at an early age. Her father, a graduate of Johnson C. Smith University, was an African Methodist Episcopalian (A.M.E.) minister and her mother was a schoolteacher. Although the parents created an educated and cultured life for their family, it did not shield the Adams from the inequity of segregation and horrors of racial discrimination. Earley recalled her childhood in Columbia, South Carolina in her memoir, One Woman’s Army: A Black Officer Remembers the WAC, and detailed the intimidation by the Ku Klux Klan. This intimidation included one particular incident where they threateningly sat outside the Adams home, from dusk until dawn, because Reverend Adams was the president of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The Adams parents modeled calmness and did not respond to the Klan’s provocation. Their modeling would serve Charity especially well, significantly when she joined the military.

After graduating as valedictorian from Booker T. Washington High School, Adams entered Wilberforce University, a private, historically Black university that is affiliated with the A.M.E. Church. Upon receiving her Bachelor of Arts degree in mathematics, physics and Latin in 1938, she returned to Columbia, South Carolina and taught math to high school students. At this time, she also began working on her Master of Arts degree from the Ohio State University and planning for her next stage in life.

However, Adams, like so many Americans could not foresee that the U.S. Navy base, including the United States Pacific fleet, at Pearl Harbor in Oahu, Hawaii would be struck by a surprise attack from Japan on December 7, 1941. The Japanese military strike caused the death of 2,335 U.S. military personnel and 68 civilians and 1178 persons were wounded; the sinking of 9 ships and severe damaging of 21 ships, 3 of which were irreparable; 188 aircrafts destroyed and 159 others damaged. This attack on Pearl Harbor was the gravest attack on the United States caused by a foreign country during peacetime in its history. Referring to it as “… a day that will live in infamy …” by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Japan’s attack prompted the involvement of the United States to enter, as an Allied Power, World War II when Congress declared war on Japan the next day, December 8.

Ironically, the entry of the United States into the war provided African-American men with opportunities far greater and more diverse than during peacetime, as the country was still recovering from the economic depression after World War I. The vacancies left behind by the thousands of Black men volunteering for military service were often administrative and needed to be filled. This need was met by the War Department, whose policies had been recently revised to proportionately align African-American volunteers with the African-American population. The War Department actively campaigned to recruit women and in October 1941, the Advisory Council to the Women’s Interests Section (ACWIS) was created. The council brought together members of 33 of the most influential social service organizations in the United States.

Most notable in this newly-created council was Mary McLeod Bethune, president of The National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) and the director of Negro Affairs of The National Youth Administration. She was a trusted associate of and special assistant to Henry L. Stimson, the U.S. Secretary of War and an especially good friend of The First Lady of the United States, Eleanor Roosevelt. She also was the only African-American woman member of the “The Black Cabinet”, prominent African-Americans who informally advised President Roosevelt on affairs in the Black community. As the assistant director of the Women’s Army Corps, she organized the women’s officer candidate schools and lobbied for the inclusion of African-American women into the military. Bethune was amazingly inspiring to many Blacks. Her appeal to Black women who wanted more for a career than teaching, nursing and performing domestic work as well as to others who had been formally educated was strongly heeded. One of those who heeded this call was Charity Adams.

In July 1942, Adams, as a university graduate, enlisted into the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). She was one of 39 Black women enlisted in the corp. She completed basic training at Fort Des Moines of Iowa in August. By September, Charity Adams became the first African-American woman to be an officer, a commander of Company 8, over Basic Women Training.

In this position, she introduced and assisted civilians in their transition to military life. She was highly efficient and so productive at running her company, that she was promoted to “Captain” and sent to the Plans and Training section at Fort Des Moines. There she oversaw basic training that was more centered toward developing skills, including office administration. In her new position, Adams presented data to various military supervisors regarding the relations of race and gender. She actively advocated for African-American women to be employed in transport and other areas from which they had historically been excluded. Adams also worked for African-American women to be employed, post-WAAC graduation, in professional positions, such as communications operators, drivers, librarians and even mechanics, that were barred from them.

(No copyright infringement intended).

While some military bases had hired these Black female enlisted personnel, others placed them in positions of service, such as working in the kitchens and cleaning. To be fair, many Blacks, prior to service in the military, had been poorly educated due to limited or even nonexistent opportunities based on racial segregation and discrimination. To counter this deficiency, supplemental education, including an “opportunity” school, was provided at Fort Des Moines. Additionally, Colonel Oveta Culp Hobby, director of the WAAC, converted the “Women Auxiliary Army Corps” to the “Women’s Army Corp” in 1943 in order to expand the advantages offered to women. With this change, new professions as well as medical and insurance benefits previously only available to men in the military, were now available to military women. Culp and Adams believed this new conversion would appeal to professional and university-educated women.

Although this measure worked, segregation was still present, even in the WAC. In 1945, Charity Adams was appointed to the rank of “Major” and took command of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, also known as “The 6 Triple 8s”. This battalion included approximately 832 African-American women as enlisted members and 31 African-American women officers. It was newly created and had the critical responsibility of securing and directing all mail to more than seven million military personnel and Red Cross workers stationed in Europe. This was an especially critical mission, inspecting mail to ensure that subversive content and contraband materials detrimental to the United States was intercepted.

(No copyright infringement intended).

During their time of active service, “The 6 Triple 8s” were stationed in Birmingham, England; Rouen, France and finally, in Paris France. Adams’ organizational skills were exceptional. To ensure that the mail was properly delivered, she divided her battalion into 5 companies who worked 3 shifts, providing 24-hour coverage. On an average day, the 6888th battalion handled 65,000 pieces of post. Adams categorized the activities of each military branch and service organization and their accompanying locations. With the motto of “No mail, no morale”, the 6888 members worked in dangerous conditions, including in abandoned, freezing and damp warehouses and pest-infested offices.

Adams also set the tone of her authority and firm stance against racial segregation. She refused Red Cross-donated equipment for a new recreation center built separate for Blacks, as they already were utilizing the recreation center that Whites used. Adams also prepared to file charges against a general who threatened to court-martial her for disobeying orders when he said he was sending for a White officer to get her battalion in order. In her autobiography, Adams said that her response was “Over my dead body, sir”, as she felt he was undermining her abilities and experience by violating military protocol and promoting racial segregation. They both refrained from their threatened pursuits of actions and came to respect other, as per Adams.

She also promoted the positive interaction between her soldiers with Whites, whether as military or civilians, especially when many White Europeans’ only impression of Black women had been the negative portrayals promoted in the media. To boost morale of her soldiers, Adams created a beauty salon that met the unique needs of Black women and she encouraged the refusal to support segregated public facilities, such as hotels and restaurants, while the battalion members were on leave.

(No copyright infringement intended).

World War II ended on September 5, 1945 and in December, Charity Adams was promoted to the rank of “Lieutenant Colonel.” In 1946, she requested to be discharged from the military. Upon her release from service, the NCNW presented her with an award for her distinguished service in the military. She resumed her graduate studies at Ohio State, earning a Master of Arts degree in vocational psychology. In 1949, she married Stanley Earley and they lived for several years in Zurich, Switzerland while her husband completed medical training to be a physician. In 1952, they returned to the United States, settling in Dayton, Ohio. They would have two children, Stanley, III and Judith.

Adams’ life was highly active after her time in the military ended. The recipient of numerous accolades and honorary doctorate degrees from her alma mater, Wilberforce University and the University of Dayton, Adams was involved in work that was varied. Her post-WAC life included serving as an administrator at Tennessee State University and Georgia State College. She was active in the Dayton community, serving on boards such as that of Dayton Power and Light and the Board of Governors of the American Red Cross. She also volunteered with outreach organizations including The United Negro College Fund and co-directed the Black Leadership Development Program.

On January 13, 2002, Charity Edna Adams Earley passed away at the age of 83 years old. Her wisdom and strength serve as a model for powerful, positive leadership and her legacy of being an inspiration for African-Americans and women in the military renders her an exemplary icon to be honored.

“When I talk to students, they say, ‘How did it feel to know you were making history?’ But you don’t know you are making history when it’s happening. I just wanted to do my job.”

~ Charity Adams Earley